The assignment asked participants to write out answers to the following questions in preparation for the simulation:

First, what is the name of your assigned role, and what is her position in British colonial society?

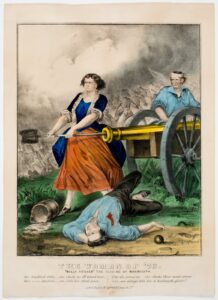

Second, what are your role’s interests in supporting/opposing America’s move to independence and nationhood in 1776? How does this person stand to benefit or lose from a separation from Great Britain? For those of you whose roles are women who were more active during the war then before, try to project back from their experiences to what they might be concerned about at the war’s onset? How might they anticipate the advantages or challenges that emerged during their life?

Third, what are the broader interests for the British colonies in building a new nation? Or why might it be better to stay part of the British empire?

Fourth, what would be an acceptable outcome to the crisis for your role? What would your role like to happen?

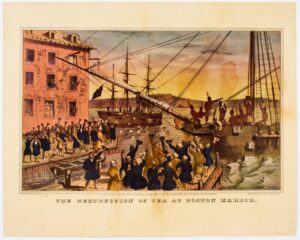

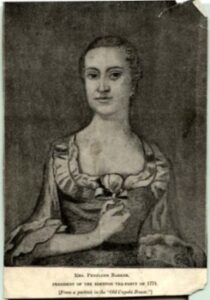

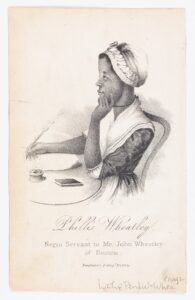

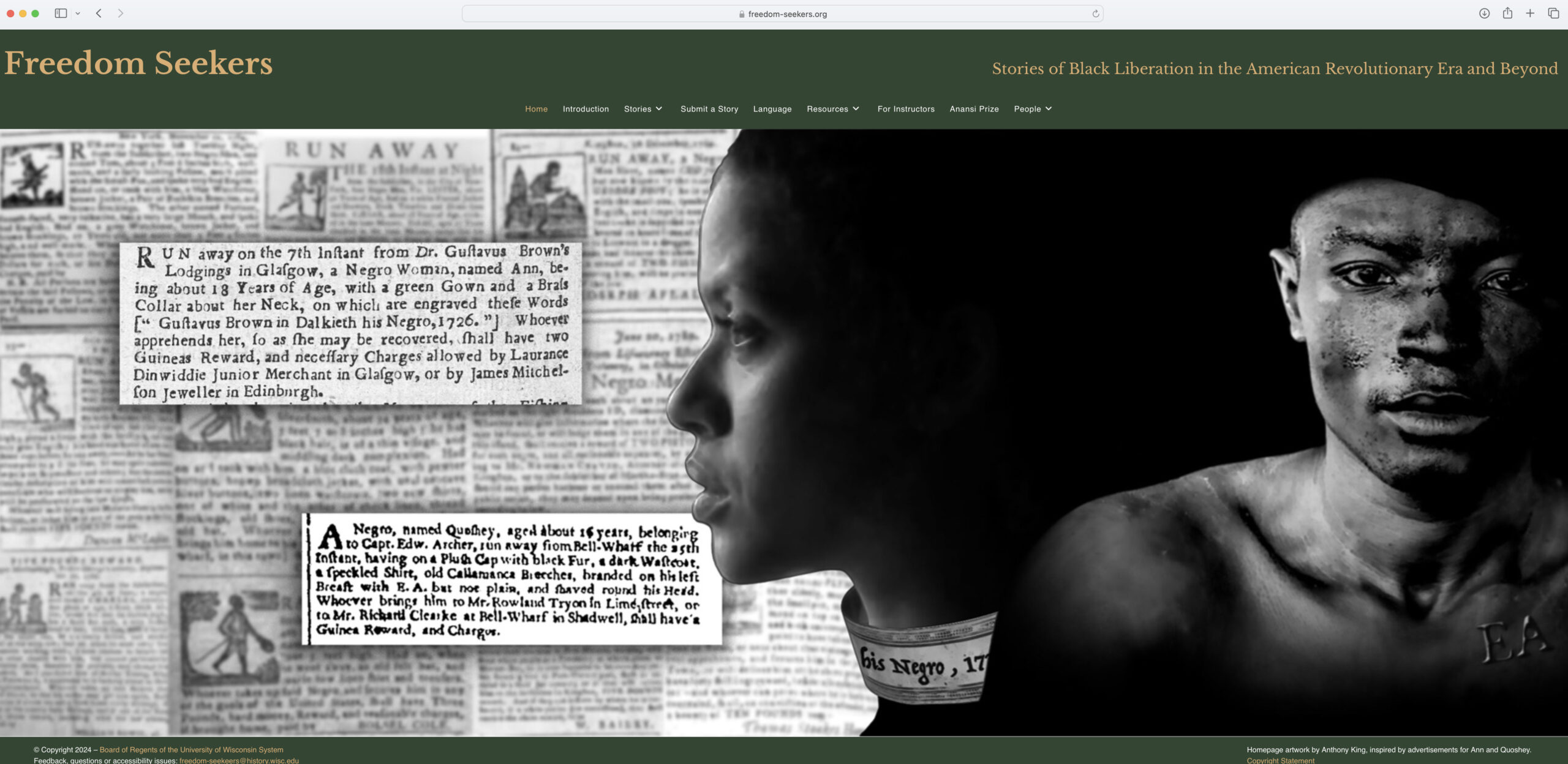

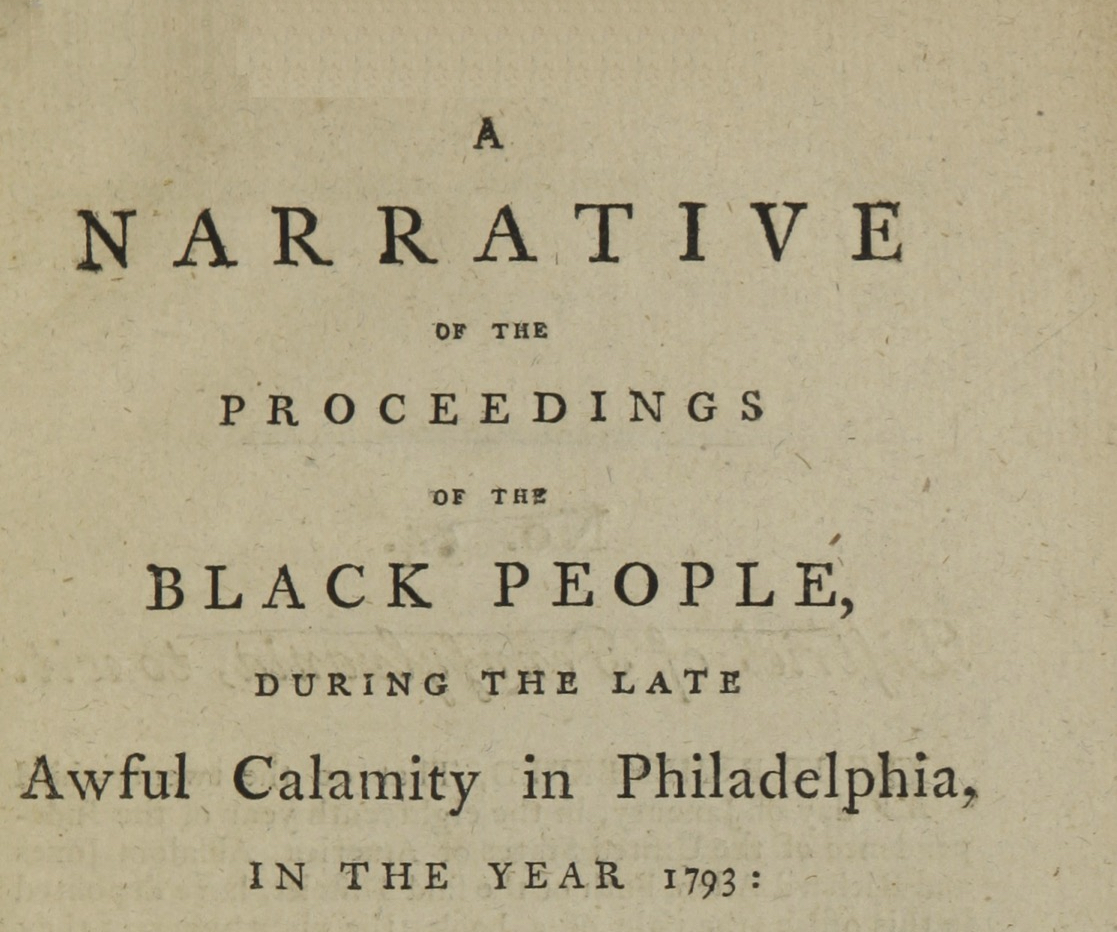

The early American women’s tea party assignment enables learning outcomes that the previous Boston Tea Party had prevented. The girls learn that Black, Indigenous, and white early American women played integral roles in politics and society. Including Black and Indigenous women’s perspectives illuminates the lives of people in early America for whom American independence was not beneficial. Thus, these diverse experiences matter for shaping historical narratives. For instance, Black women did not all either oppose or support independence. Due to the realities of either enslavement or emancipation, early American Black women’s interests were highly nuanced. Neither white colonists nor white Britons intended to aid African Americans substantially. These dynamics add scholarly sophistication to the classroom.

I facilitated this simulation twice during the 2021-2022 academic year and watched my colleague facilitate a third. Whenever possible, my colleague and I both let students choose their parts, hoping that this approach would enable agency and empowerment.

In one of my simulations, Abigail Adams and Mercy Otis Warren passed notes across the room. The notes, which I was still finding days later, didn’t have real words on them, just scribbled lines. They used the resources that I provided from Massachusetts Historical Society’s online primary sources to discern that Adams and Warren were friends in real life. As material culture, the notes suggested the girls’ enthusiasm for this activity.