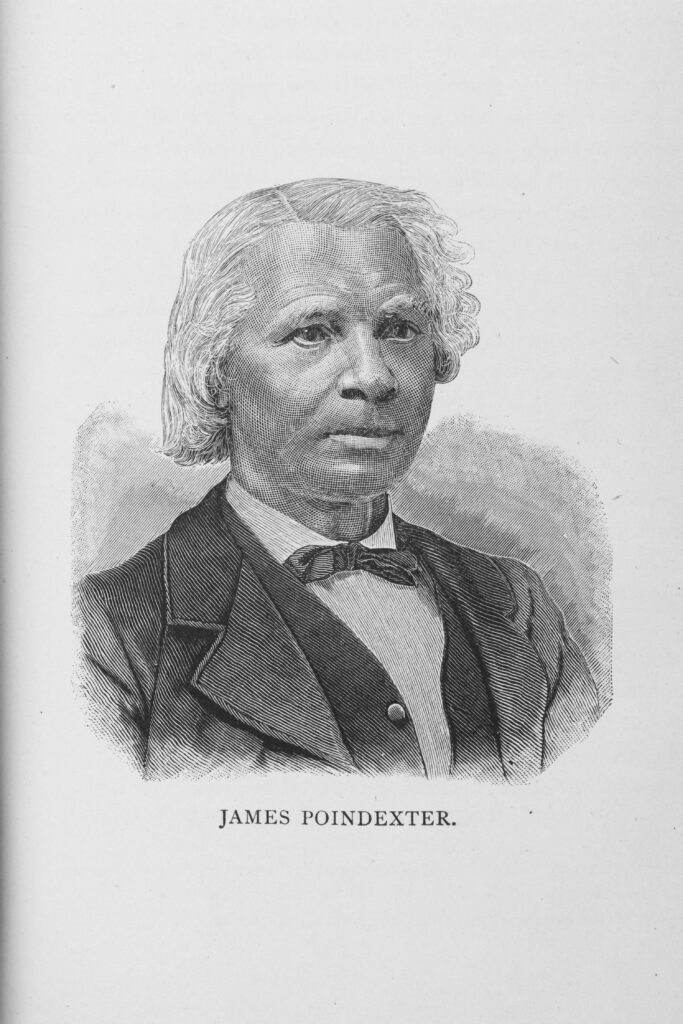

As the new year opened in 1851, Ohio Black abolitionists gathered in Rev. James Poindexter’s Second Baptist Church in the capital city of Columbus, Ohio, for a four-day meeting. Poindexter’s congregation, housed in a stately brick structure on East Gay Street, was known for its activism in the Underground Railroad, an operation that had taken on a greater level of importance with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850.

“Nativity Gives Citizenship”: Teaching Antislavery Constitutionalism through the Black Convention Movement

As a teacher, the Black convention movement in the 1850s has helped me to broaden my story of the origins of the Civil War, especially the pitfalls to avoid when it comes to focusing too heavily on the controversy over slavery in the territories.

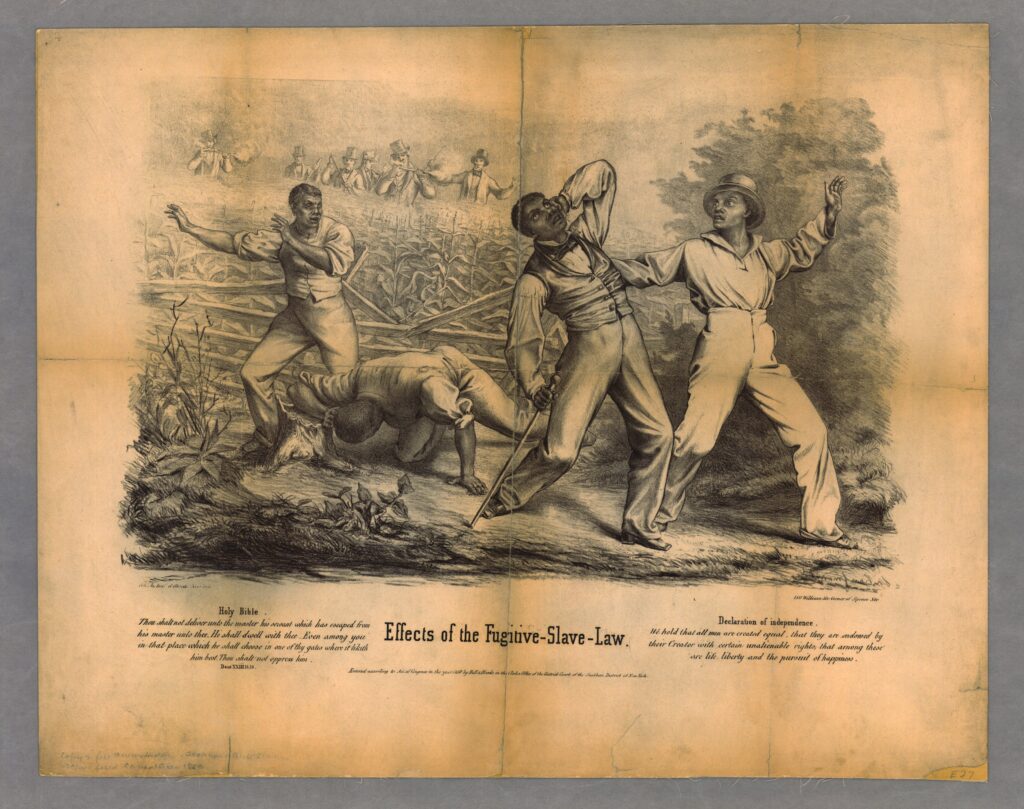

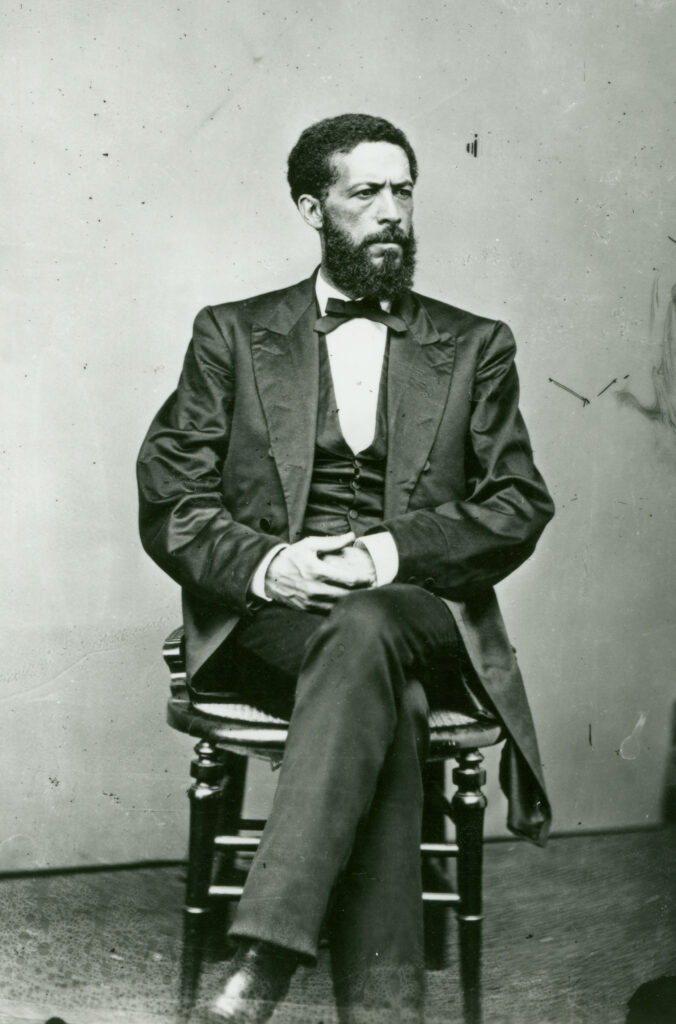

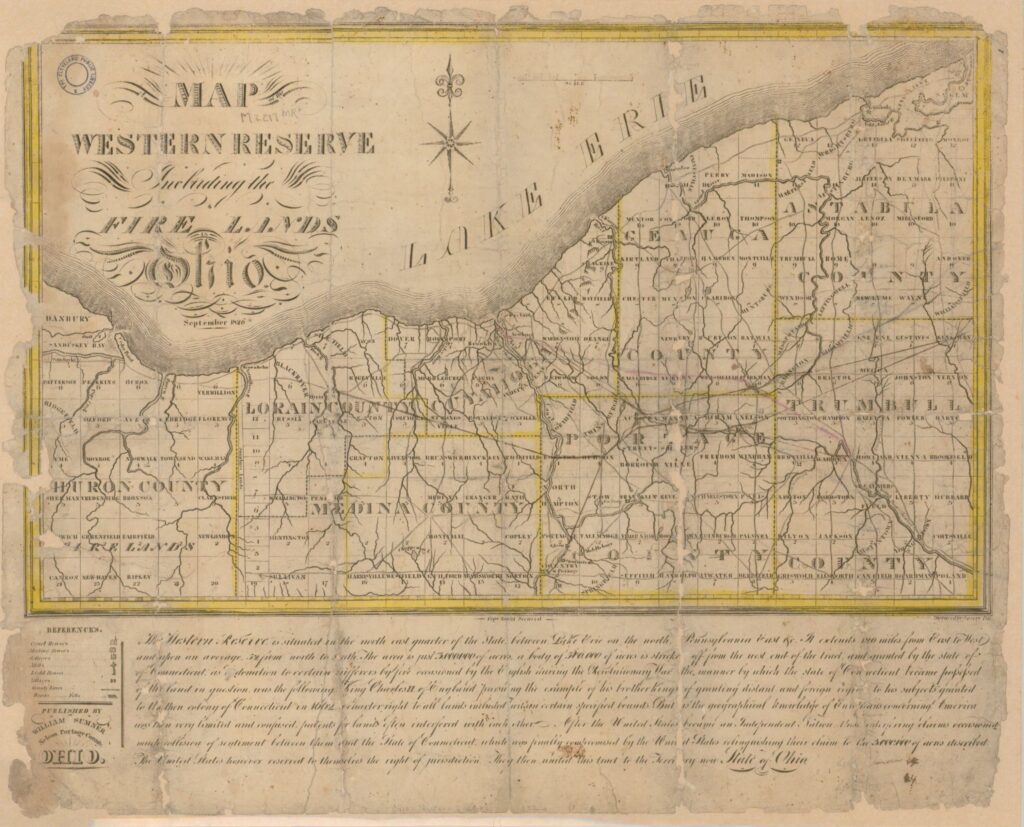

As part of the Compromise of 1850, the new Fugitive Slave Law, a much more stringent version of its 1793 cousin, permitted African Americans in the North to be seized solely based on the affidavit of anyone claiming to be his or her owner or working on the owner’s behalf. It was without question the most intrusive enactment of federal authority prior to the Civil War. Black abolitionist H. Ford Douglas, who hailed from Cuyahoga Falls not far from where I teach at Western Reserve Academy in Hudson, declared at the Columbus gathering that after nine months of debate about how to settle the vexing question of slavery in the territories, Congress, with the Fugitive Slave Act, ended up striking “down the writ of Habeas Corpus and Trial by Jury—those great bulwarks of human freedom.” It was a law, according to Douglas, “unequalled in the worst days of Roman despotism.” Western Reserve Academy has a rich history in the abolitionist movement in northeast Ohio. By the late 1840s, a prominent group of young Black activists, including John Mercer, Charles Langston, William Day, and H. Ford Douglas were well-known figures in the area.

Ironically, it was a call for federal power by white Southerners who had steadfastly opposed for decades the aggrandizement of the federal government out of fear that it would threaten their hold on the slave system. President Millard Fillmore, who had taken office after the death of Zachary Taylor, signed the act into law on September 18, 1850, creating a panic in African American communities across the North. Just days after the law was enacted, James Hamlet, a fugitive from Maryland living in New York City, was captured and brought to a jail in Baltimore. Abolitionists eventually secured Hamlet’s freedom by purchasing him for eight hundred dollars. Others were not so fortunate. Throughout the 1850s, thousands of African Americans fled the United States to Canada.

Blacks, both enslaved escapees and long-term free residents, were now placed in considerable danger. A Black convention in Cincinnati opened with a harsh indictment against a nation that “hunted” slaves “like beasts from city to city, and dragged [them] back to the hell from which they fled—the Government which should protect them,” was instead “prostituting its powers to aid the villains who hunt them.” Personal liberty laws on the statute books in almost all northern states were set to be ripped away by the new federal business of slave hunting. “This enactment—unworthy of the name of law—reverses” the presumption of innocence by “prohibiting what is right, and commanding what is wrong,” declared John Mercer Langston at the 1851 Columbus convention. On a motion of John’s older brother Charles, a petition was drafted and sent to the U.S. Congress calling for the repeal of the “unconstitutional” law.

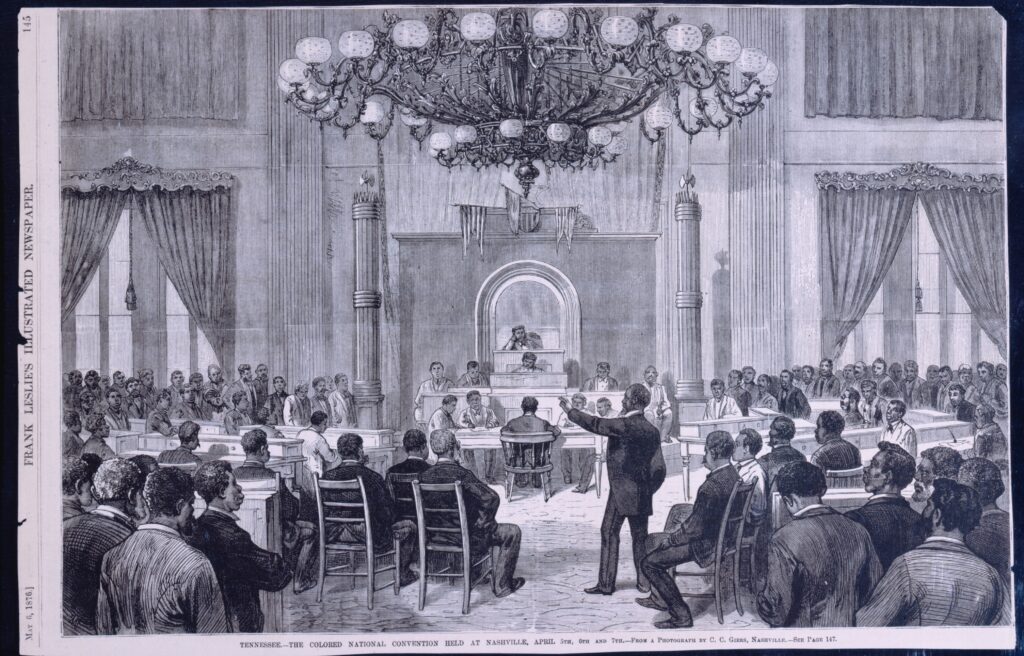

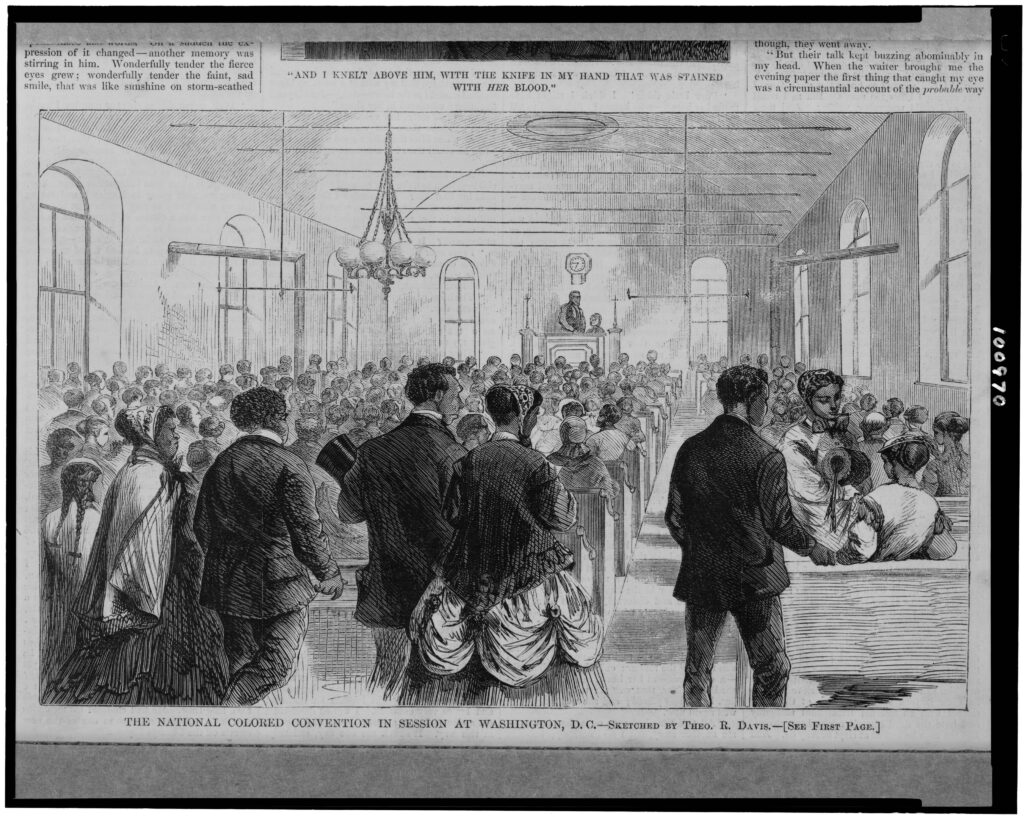

Black conventions in the early 1850s hosted a wide-ranging conversation about the crisis of constitutionalism that stemmed from the passage of the draconian Fugitive Slave Act. As legal scholar James Fox has persuasively argued, these Conventions “provided Black leaders and activists a forum to share ideas, debate strategies, and engage as a community in forming and reforming their identities as Black American citizens.” National Conventions met over a dozen times before the Civil War in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and New York. The first Ohio convention was in 1837, with ten more prior to the Civil War. Ohio actually served as the catalyst for the first national Black Convention in Philadelphia in 1830 which stemmed from outrage over the attempt of Cincinnati officials to physically remove African Americans.

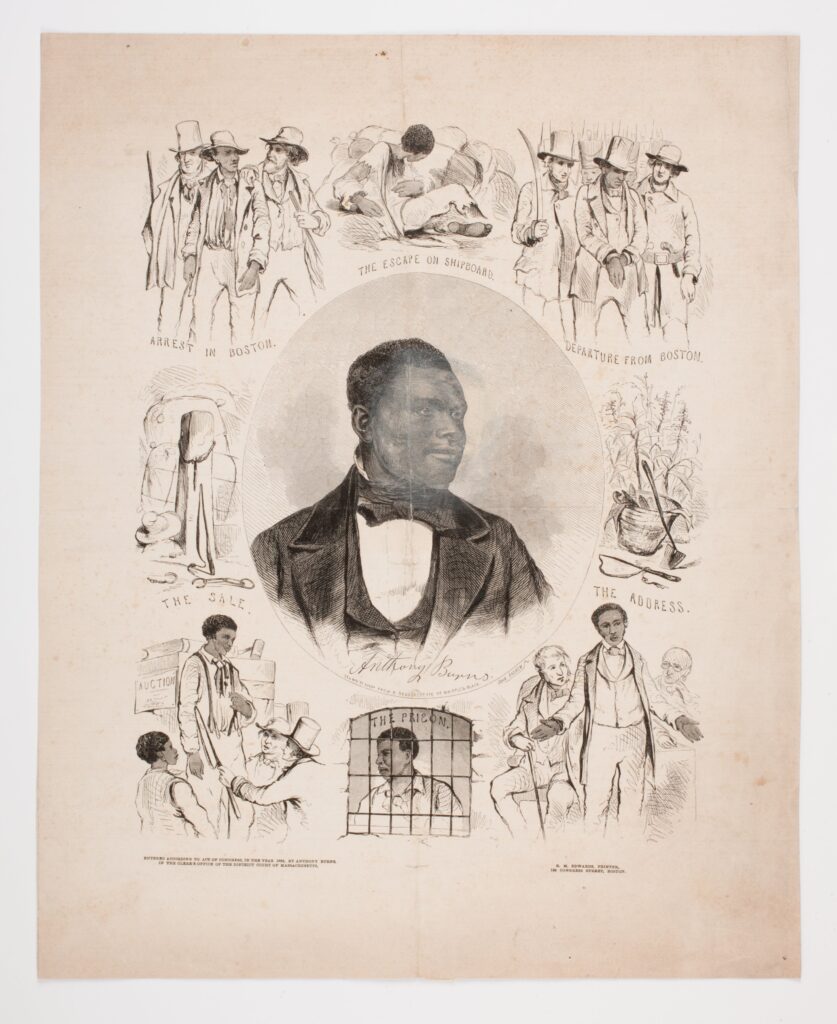

Over my many years in the high school classroom, I’ve spent considerable time on the story of obstructions to the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, covering dramatic rescues in Boston, Massachusetts, and Syracuse, New York, along with abolitionists’ armed resistance against slavecatchers at Christiana, Pennsylvania. These cases were often referenced at Black conventions, including one held in Cincinnati in 1852 at the Union Baptist Church:

We Sympathize deeply with man Shadrach, of Boston, who fled from the American Fiery Furnace, to its contrast—the snows of Canada, with Jerry, who at Syracuse was transported from the American “Babylon” . . . with the men at Christiana who so honored a Christian name, by protecting their homes, and refusing to be made slaves; and have learned from their example that liberty is dearer than life, and eternal vigilance its only guarantee.

At the Cincinnati 1852 convention, a resolution was passed declaring the “law of God” over “human enactments” and the “duty to obey God rather than man” paramount. Several of my students recognized that this ideological position stood in stark contrast to the message in President George Washington’s 1796 Farewell Address which we had spent time on when covering the political drama of the 1790s. Washington’s address set up the debate over the “duty of every individual to obey the established government.”

The formation of northern vigilance committees and committees of safety, which pledged to sound the alarm should slavecatchers appear, always provided ample opportunity for discussion in the classroom. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in September 1850, slavery was no longer an abstraction, limited in scope to the southern states, but was now a major local concern from New England to the Midwest. Captures and rescues under the Fugitive Slave Act provided real-life drama on northern city streets for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The political significance of rescues, along with federal trials for those who aided fugitives, contributed in substantive ways to the political crisis that severed the United States. For African Americans in the North the law, which provided the federal government with authority to reach into the states in unprecedented ways, made them more vulnerable than ever to kidnappers who were now aided by draconian provisions that removed rights to due process.

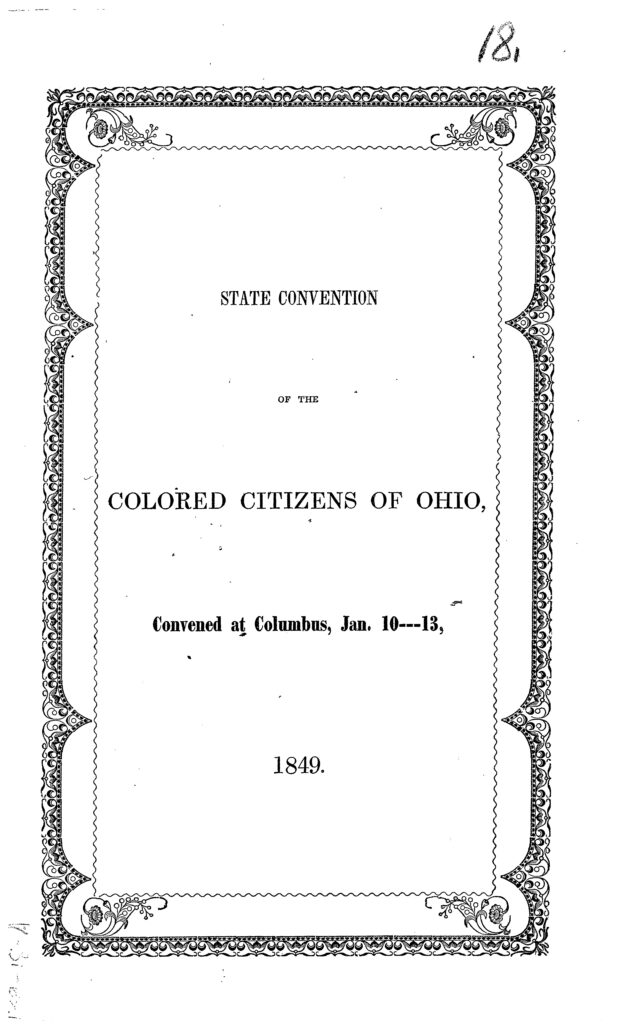

While white antislavery leaders attacked the legal apparatus protecting the rights of slaveholders to reclaim property, fidelity to the legal process and protections for African Americans was often not extended to the realm of civil rights and the complete removal of the odious Black laws passed by numerous northern legislatures. Ohio’s Black Laws, enacted in the early nineteenth century, required a certificate of freedom and bond for African Americans migrating into Ohio and forbade “black or mulatto” testimony in court cases where a white person was a party. They were largely repealed in 1849, thanks to the advocacy of Black leaders. As historian Kate Masur has noted, in Ohio “Black activists had persistently and creatively demanded repeal, and growing numbers of white people had become persuaded that racist laws were unacceptable and un-American.” But restrictions on Black voting remained, along with limitations and prohibitions on other aspects of life. Blacks enjoyed some ordinary rights and privileges but faced high levels of statutory discrimination in major areas of life, including marriage laws, housing, jobs, schools, and access to the ballot.

The hardening of racist sentiment in the North corresponded with the rise of the two-party system. By the mid-1830s, a clear majority of white northerners began to perceive the nation’s basic problem as not just slavery but also the presence of Blacks in the country, free as well as enslaved. This is where the pathbreaking Colored Conventions Project served to open new doors for me as a teacher.

It was not until I read about P. Gabrielle Forman’s pathbreaking work on the Colored Conventions Project that I began to see a deeper history than high-flying rescues or dramatic courtroom dramas. The story that I now sought to present to my students centered on how the Fugitive Slave Act overruled a presumption of citizenship for free Blacks in the North. However, it was more than simply access to the writ of habeas corpus. Black abolitionists offered a profound re-reading of the text of the Constitution and the power of the Declaration of Independence that had far reaching implications. In the 1850s, the Fugitive Slave Act certainly raised questions relating to resistance, but it also helped to bring attention to the powers and prerogatives of the states when it came to the privileges and immunities of citizenship. State-level agitation in Ohio for civil rights mirrored state-level opposition to implementation of the law.

In reading the Ohio Black convention debates, my students began to see how the words of Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence and the Preamble to the 1787 Constitution were turned into a new political creed by Black reformers. Southern white leaders, as historian William Wiecek noted long ago, were on record opposing Jefferson’s Declaration as rhetorical flourish in a political manifesto as early as 1821. But for Ohio’s William Howard Day, an Oberlin graduate and the editor of The Aliened American, Cleveland’s first Black newspaper, the Declaration and the Constitution were the “foundation of liberties” with coequal status.

What became clear to my students as our classroom examination developed was that “privileges or immunities,” “due process,” “equal protection,” and rights of citizens of the United States was something that Black activists had been talking about for decades. I was able to do an overview with my students of the free Black opposition to the American Colonization Society in the early 1830s that helped to illustrate this. It was clearly not something that first arose during the post-Civil War period.

Across the northern free states, according to Kate Masur, Black “activists forcefully insisted that laws that made explicit race-based distinctions had no place in American life.” These activists “pressed new ideas about citizenship, individual rights and the proper scope of state power.” The discourse on the Constitution at Black conventions clearly demonstrated that the process of creating constitutional law involved more than lawyers in the courtroom. Ohio Black leaders declared that they would “continue to agitate” before “the people, to circulate petitions among the people, and memorialize” the state legislature. They would not stop until Ohio became a “true democracy, conservator of equal and impartial liberty.” By making claims to citizenship and invoking the founding documents, Black leaders expanded the reading of the constitutional text. Jefferson’s Declaration was viewed as having a direct link to the Constitution and creating an obligation for civic and political equality.

By the early 1850s, the privileges and immunities clause in the Constitution had an important place within antislavery constitutional ideology. The vast majority of Black abolitionists insisted that the privileges and immunities of citizenship in the Constitution were general and were enjoyed by all citizens. In a previous Commonplace article that I wrote about the 1842 Dorr Rebellion in Rhode Island, I encountered Black abolitionists, including Ichabod Northup, who challenged both the Dorrites and their “People’s Constitution,” along with the Rhode Island government to allow Blacks into the body politic by eliminating an 1822 statute that barred them from the polls. Black northerners were free but far from equal. Black leaders petitioned the Rhode Island General Assembly for an end of “that odious feature of the statute, which in making the right of citizenship identical with color, brings a stain upon the state, unmans the heart of an already injured people and corrupts the purity of republican faith.” I was able to draw connections between Black leaders in Rhode Island and Ohio since they both worked towards the removal of “white-only” clauses embedded into state laws. Rhode Island Black leaders made clear that it was through “birthright” that they deserved civil and political rights, a clear conception that the privileges and immunities of citizenship were also tied to being born on “native soil.”

William Yates’ remarkable 1838 pamphlet “The Right of the Colored Man to Suffrage, Citizenship and Trial by Jury” proved to be a great teaching tool and one that students enjoyed exploring in the classroom. Yates’ writings covered citizenship in a manner that would later guide radical Republicans after the Civil War, especially questions relating to birthright citizenship. “We are human beings, and we are Americans; we are entitled to the same rights as white Americans,” wrote Yates. “Free persons of color are human beings, natives of the country—for such of we speak—and owe the same obligations to the State, and to its government as white citizens.” They have an “equal right to liberty—to the enjoyment and security of home and family—and of a good name and character as white men; so, to all the rights of conscience—to read, write, and print—to speak, teach, and debate—to preach, and worship God according to its dictates—their title as the same as that of white men.” In the 1840s and 1850s, northern Blacks gained rights through agitation, legislation, and court decisions.

At the end of the 1851 Columbus convention, calls for removal of the Fugitive Slave Law did not come at the top of the list for the delegates as they assembled their resolves. The first resolution adopted was a clarion call for the elective franchise and a removal of the remnants of Black Laws from the statute books. The year before, at another state convention in Columbus, delegates decried how Blacks in the North were “only nominally free.” The right to vote was labeled a “birthright.” This was the focal point of William Day’s and Charles Langston’s powerful closing address at the following year’s Convention: “Those of us, therefore, who were born in the United States, and reside in Ohio, are citizens of Ohio. If citizens of this state, entitled by the United States Constitution, to all the rights and immunities of citizens of the several states. The elective franchise being among these rights.” In 1852, in Cincinnati, the “rights and immunities of American citizens,” in particular, “native born American citizens,” were on the table for discussion. Black activists were constantly trying to reshape the national debate.

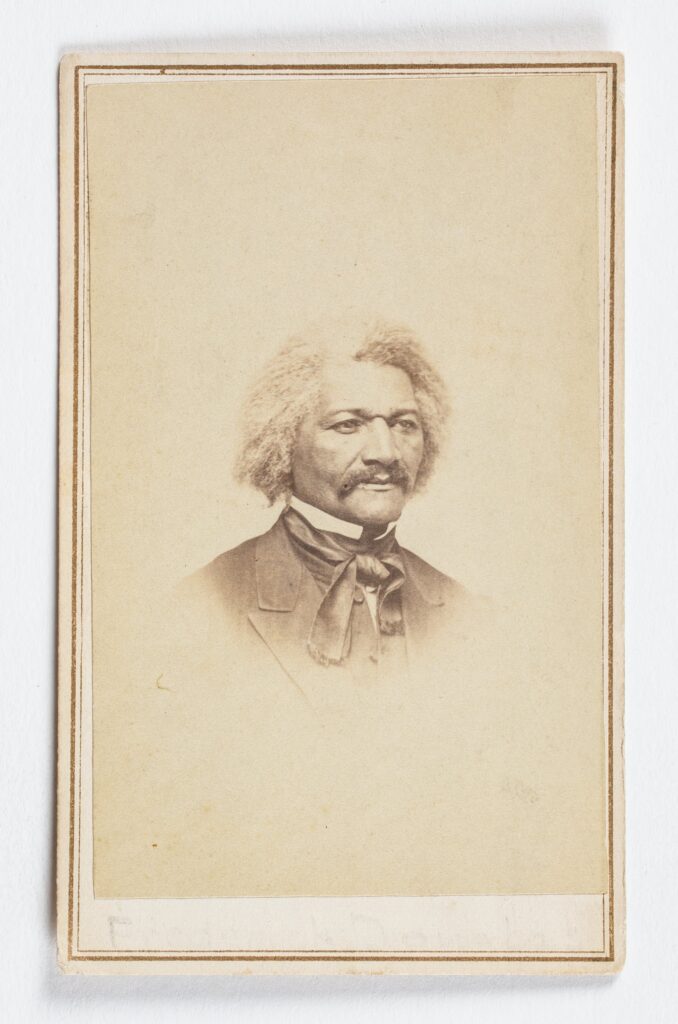

My classroom is just a stone’s throw from the courtyard of our historic chapel where Frederick Douglass delivered a commencement address at what was then Western Reserve College. Douglass’ 1854 address, later published as a pamphlet and sold widely in the North and Europe, was his first address on a college campus. Douglass chose not to provide the students and families in attendance with a jeremiad on the constitutional crises that was gripping the nation with the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act just weeks before, or the ongoing controversy over fugitive slaves. Douglass had actually written widely on the Anthony Burns affair in Boston and had openly defended the killing of a deputy U.S. marshal in the city during a confrontation with abolitionists attempting to prevent Burns from being returned to slavery in Virginia. He was on record encouraging free Blacks to move to Kansas to help prevent the territory from becoming a slave state. Rather, at Reserve, Douglass focused on “Human rights,” to get the young audience to understand how the corrupting influence of slavery spread in the North through racist sentiments and laws that led to the belief in the innate inferiority of Black Americans. Douglass reminded the audience that all Americans stood “upon a common basis.” All “mankind” has the “same wants,” arising out a “common nature,” proclaimed Douglass. God “has no children whose rights may be safely trampled upon.” Douglass’ speech was a clarion call to the student body—all white at the time—to not become caught up in the standard racial prejudices of the day. Douglass emphatically declared that he was a “citizen” of the United States, but nonetheless, a citizen “rolling in the sin and shame of Slavery,” a reference to racial discrimination in the North.

Douglass’ invocation of citizenship at Western Reserve College, along with the wide-ranging discussion of the meanings and prerogatives of birthright citizenship at Black conventions throughout the 1850s, helped students see the long and complex story of the public meaning of section one of the Fourteenth Amendment. By the end of the decade, after the notorious Dred Scott decision was handed down in 1857, Ohio’s Black leaders, including John Mercer Langston, continued to hammer home the importance of birthright citizenship. In the “name of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution of the United States, the ancient policy of the Fathers of the Republic, the well-established doctrine that nativity gives citizenship” is what Black leaders wanted to keep in the forefront of people’s minds. “We are here, and here we intend to remain,” proclaimed Langston in closing his Cincinnati address. Black abolitionists kept the citizenship question at the forefront of politics in the late 1850s.

As a teacher, the Black convention movement in the 1850s has helped me to broaden my story of the origins of the Civil War, especially the pitfalls to avoid when it comes to focusing too heavily on the controversy over slavery in the territories. The demand of antislavery activists for accused fugitives to be guaranteed a jury trial was an implicit recognition of Black citizenship. In addition, delegates to Black conventions throughout the decade pushed for more than mere due process rights in the face of attempts to enforce southern law in northern states. Just as there was a militant obstruction of the operation of the Fugitive Slave Law on northern soil, Black leaders were militant in their call for fuller measures of equality. They helped to develop the concept of birthright citizenship, a later hallmark of the Fourteenth Amendment, and passionately promoted the understanding that African Americans had a fundamental right to the equal protection of their natural rights by the government. There was nothing the white South feared more.

Further Reading

My students and I benefitted greatly from engaging with historian Kate Masur’s Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, From the Revolution to Reconstruction (New York: W. W. Norton, 2021). It is a must read for any teacher trying to bring the long history of civil rights into the classroom. Masur’s chapters on Ohio worked well in the classroom in conjunction with documents from Black conventions in the 1850s in Ohio that can be found on the Colored Conventions Project website. With my students I focused on the following gathering of Black abolitionists: 1849 Columbus, 1850 Columbus, 1851 Columbus, 1852 Cincinnati, and 1858 Cincinnati.

Selections from Manisha Sinha’s comprehensive account of the abolitionist movement, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), provided much needed context for the students. I learned a great deal from legal scholar James W. Fox’s superb lengthy article, “The Constitution of Black Abolitionism.” Fox’s underappreciated scholarship fills a large hole in the discussion of antislavery constitutionalism. Historian H. Robert Baker’s article, “The Fugitive Slave Clause and the Antebellum Constitution,” Law and History Review 30 (no. 4, 2012) helped my students understand the operation of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. Paul Finkelman’s article, “The Strange Career of Race Discrimination in Antebellum Ohio,” Case Western Reserve Law Review 55 (no. 2, 2004) was very helpful. See also Paul Finkelman, “Prelude to the Fourteenth Amendment: Black Legal Rights in the Antebellum North,” Rutgers Law Review 17 (no. 1, 1985-1986).

Eric Foner’s Gateway To Freedom: The Hidden History Of The Underground Railroad (New York: W. W. Norton, 2015), provided my students with an engaging overview of clandestine efforts in the antebellum period to escape from slavery. Selections from R. J. M. Blackett’s The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), Steven Lubet’s Fugitive Justice: Runaways, Rescuers, and Slavery on Trial (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010), and H. Robert Baker’s The Rescue of Joshua Glover: A Fugitive Slave, the Constitution, and the Coming of the Civil War (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2006) were also utilized.

In preparing to teach the class over the summer, I benefited from reading Van Gosse’s The First Reconstruction: Black Politics in America from the Revolution to the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021), along with Christopher James Bonner’s, Remaking the Republic: Black Politics and the Creation of American Citizenship (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). For a number of years now, James Oakes’ scholarship has informed my thinking about a host of topics, including issues of race and citizenship, antislavery politics, and the antislavery constitutionalism. Teachers should read Oakes’ The Crooked Path to Abolition: Abraham Lincoln and the Antislavery Constitution (New York: W. W. Norton, 2021) along with The Scorpion’s Sting: Antislavery and the Coming of the Civil War (New York: W. W. Norton, 2014). Oakes’ groundbreaking scholarship builds upon arguments first introduced by William Wiecek in his classic work, The Sources of Antislavery Constitutionalism in America, 1760–1848 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977).

This article originally appeared in March 2023.

Erik J. Chaput, Ph.D., teaches at Western Reserve Academy in Ohio and in the School of Continuing Education at Providence College. He received his doctorate in early American History from Syracuse University. He is the author of The People’s Martyr: Thomas Wilson Dorr and His 1842 Rhode Island Rebellion (2013) and has edited multiple letter collections with historian Russell J. DeSimone on the Dorr Rebellion Project website. This is his fourth teaching article for Commonplace. His previous articles, including a piece on the 1864 Black Convention in Syracuse, can be found in the archive section.