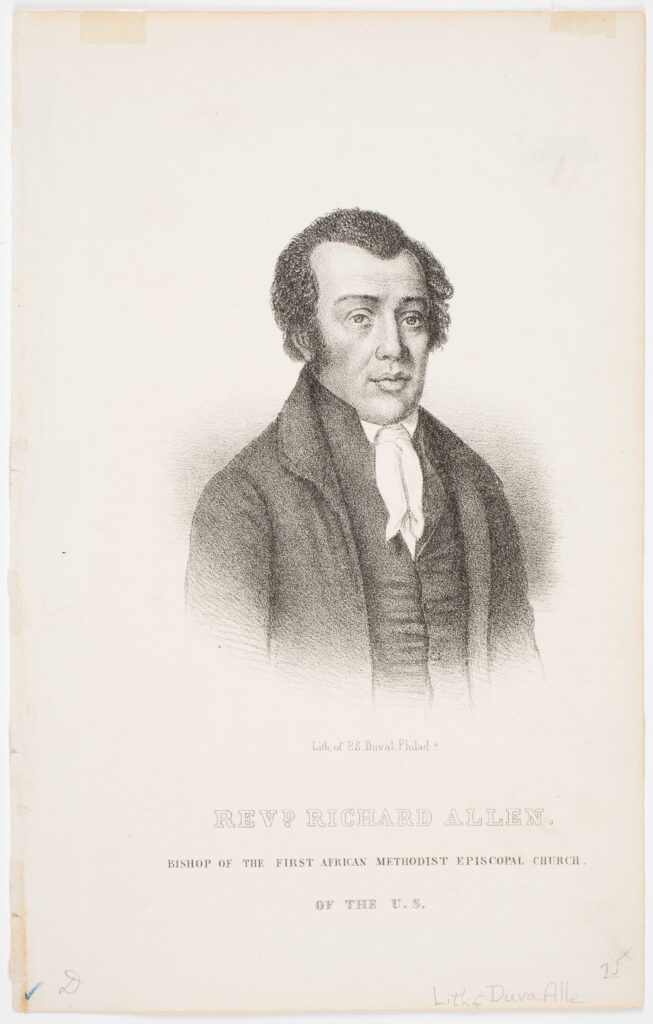

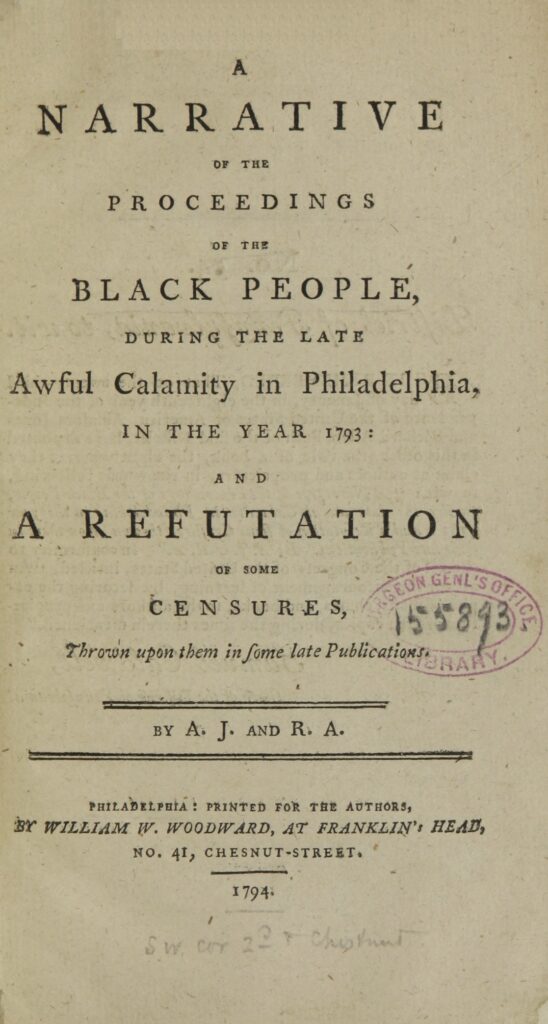

Specialists of the early national period are likely familiar with Absalom Jones and Richard Allen’s A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the Year 1793: And a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown Upon Them in Some Late Publications (1794). Although Jones and Allen’s account describes a very specific “awful calamity”—the yellow fever epidemic that struck Philadelphia in 1793—their narrative is equally concerned with a larger constellation of overlapping crises stemming from the Atlantic slave trade, including the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, the Haitian Revolution that began in 1791, and what Joanna Brooks has described as the racial panic following Pennsylvania’s Gradual Manumission Act of 1780. Like many of us, I anticipated that Jones and Allen would be particularly relevant to teach during our most recent public health crisis, but I’ve found that their text resonates beyond the theme of pandemic writing. A Narrative is written less to make sense of a past temporary crisis than to mark and anticipate the present and future effects of partial accounts of that crisis. A Narrative uses graphic sensory imagery to return readers to past scenes of distress, but with the goal of correcting the historical frame that is already informing their understanding of those events. Throughout their account Jones and Allen shift between urgently registering the pressing material effects of crisis and contextualizing those effects within a longer, unfinished history. I’m interested in what Jones and Allen’s narrative strategies can offer students in the face of adjacent crises experienced as both immediate and ongoing, including the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, economic precarity, and white supremacist violence.

Teaching in Crisis with Absalom Jones and Richard Allen

For Jones and Allen, the problem was not a lack of information, but stubbornly partial accounts of that information.

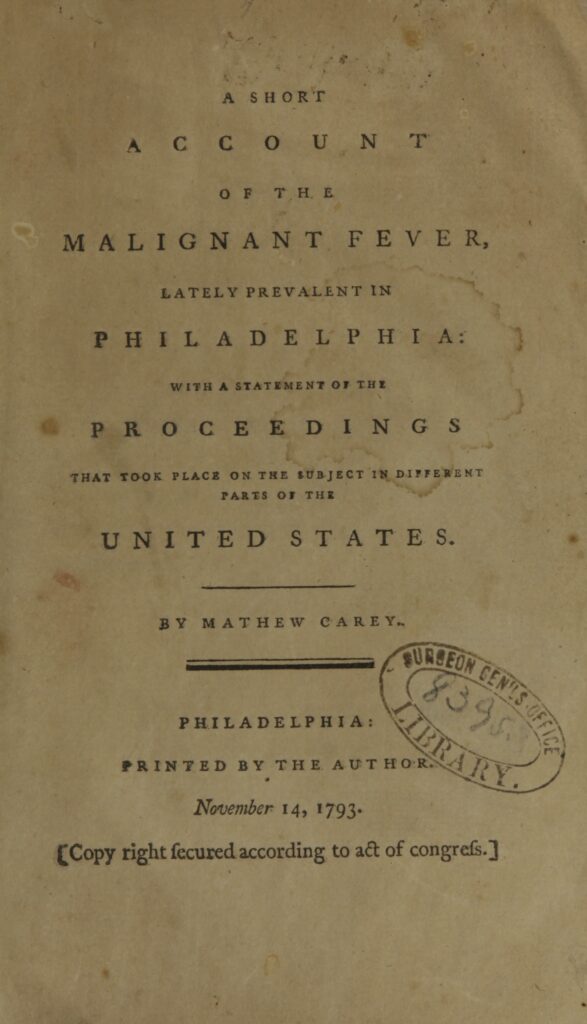

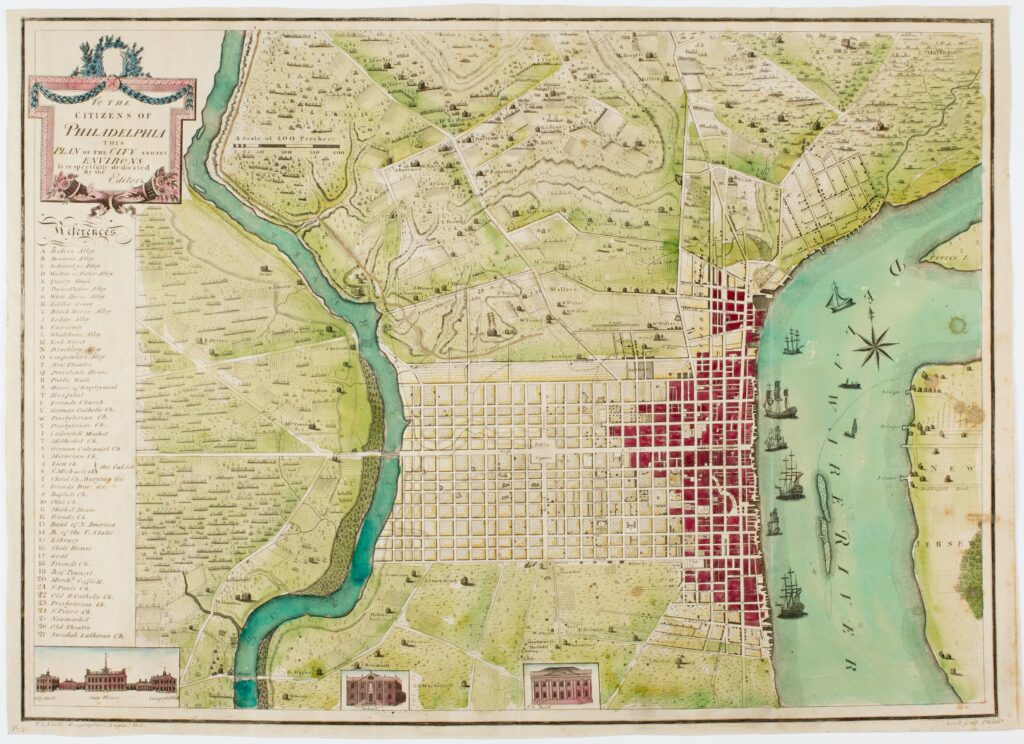

Most immediately, Jones and Allen’s account of the yellow fever epidemic can be understood as a corrective to publisher Mathew Carey’s slanderous account of the actions of Black Philadelphians in his A Short Account of the Malignant Fever, Lately Prevalent in Philadelphia (1793). In that account, Carey reproduced the incorrect theory that people of African descent were immune to yellow fever and accused Black residents who served as nurses and gravediggers of exploiting the crisis for financial gain. Jones and Allen’s response to Carey can serve as historical precedent for understanding the sharp rise in hate crimes targeting Asian Americans in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Jones and Allen positioned the experiences of Black Philadelphians during the yellow fever epidemic within a larger history of racial violence. Likewise, Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) scholars and activists have positioned these hate crimes within centuries of scapegoating rhetoric weaponized against the AAPI community in response to economic, political, and public health crises. They have also argued that this most recent threat of violence might be partially responsible for higher COVID-19 mortality rates among Asian Americans.

In addition to this direct connection between past and present, I find Jones and Allen’s narrative strategies useful for thinking about our narratives of crisis more generally. As Derrick Spires has recently argued, it’s important to understand Jones and Allen as not only responding to Carey, but as also proposing their own radical and expansive theories of citizenship. Building off this work, I’d also like to enlarge our understanding of Jones and Allen as critics of a certain kind of reaction to crisis that, as Kyle Whyte has shown, in its misunderstanding of crisis as unprecedented, justifies the expendability of certain populations. Jones and Allen’s Narrative forces readers to confront what Lauren Berlant has described as the environmental conditions of slow death, recontextualizing the yellow fever epidemic within a broader and ongoing history of violence and neglect.

Jones and Allen append to their account of the epidemic “An Address to those who keep slaves, and approve the practice” (23). This address offers a theory for why the white citizens of Philadelphia have been so “willfully blind” in their characterizations of Black health and civic duty (24). Capturing the slippage between “those who keep slaves” and those who “approve the practice,” the opening sentence of this address seamlessly shifts from description to direct address: “The judicious part of mankind will think it unreasonable, that a superior conduct is looked for, from our race, by those who stigmatize us as men, whose baseness is incurable, and may therefore be held in a state of servitude, that a merciful man would not doom a beast to; yet you try what you can to prevent our rising from the state of barbarism, you represent us to be in.” The shift in pronouns links “those who keep slaves” to the “you” of Jones and Allen’s readers: both “prevent our rising from” a “state of barbarism” that is itself a fictional construction that justifies white supremacy. The city’s post-slavery racial hierarchy depends on diagnosing Black residents as suffering from “incurable” “baseness.” Only this widened historical lens provides sufficient context for understanding why the Black residents of Philadelphia were impressed into service during the epidemic and how their public service continues to be portrayed in its aftermath.

The incorrect theory that people of African descent were immune to yellow fever led large numbers of the city’s Black residents to be impressed into service caring for the sick and disposing of bodies. The idea that Black residents were inherently immune was convenient because it justified both the impressment of Black residents as front-line health care workers and their enslavement and disenfranchisement through polygenist definitions of race. Jones and Allen open their Narrative noting that this theory of immunity was always in doubt, characterizing it as only “a kind of assurance,” while attributing their own service to “our sense of duty to do all the good we could” rather than to any confidence in their safety (3). Although the Narrative highlights that Black Philadelphians’ “distress hath been very great, but much unknown to the white people,” it also argues that this position of unknowing is one of deliberate cultivation rather than innocence (15). Although the theory of Black immunity was quickly disproven in the early weeks of the epidemic, “it is even to this day a generally received opinion in this city.” Jones and Allen note that when “it became too notorious to be denied” that Black residents were in fact dying of yellow fever, “then we were told some few died but not many.” This new claim could have been disputed by “any reasonable man” who examined the burial records of 1792 and 1793. Carefully documenting the shifting nature of the justifications for the impressment and neglect of Black residents, Jones and Allen attribute the incoherence of the medical discourse to a purposeful strategy of having “our services extorted” rather than a lack of information.

Mathew Carey did eventually revise subsequent editions of his Short Account to correct the theory of Black immunity and to temper the charges of extortion he leveled against Black nurses. Jones and Allen did not anticipate that these future editions would sufficiently counter the proliferating versions of misinformation that have already stigmatized the Black residents of Philadelphia: “Mr. Carey’s first, second, and third editions, are gone forth into the world, and in all probability, have been read by thousands that will never read his fourth—consequently, any alteration he may hereafter make, in the paragraph alluded to, cannot have the desired effect, or atone for the past; therefore we apprehend it necessary to publish our thoughts on the occasion” (13). Confirming Jones and Allen’s skepticism about the efficacy of future corrections, in the fourth edition of his Short Account (1794) Carey acknowledges that the theory of Black immunity turned out to be wrong, but he also argues that this mistake was ultimately beneficial to the city’s white residents, because it meant Black nurses were not afraid to serve. This correction only emphasizes the expendability of Black residents in the face of crisis and continues to ignore that the Black nurses described by Jones and Allen served despite understanding the risk of infection.

For Jones and Allen, the problem was not a lack of information, but stubbornly partial accounts of that information. Critiques of partiality appear throughout the Narrative: Jones and Allen refer to “partial” accounts, relations, representations, paragraphs, and men eight times. As Carey’s corrections in his fourth and fifth editions demonstrate, partial’s dual meanings of biased and incomplete operate together, as Carey’s racial bias kept him from seeing a complete picture of the epidemic, including the ways that Black residents suffered and the civic duty they performed. Although Carey accuses “the vilest of the blacks” of extortion, from his very first edition he also specifically praises “Absalom Jones and Richard Allen” for their service, declaring “it is wrong to cast a censure on the whole for this sort of conduct” (77). Refusing to serve as exceptions that prove Carey’s rule, Jones and Allen respond by claiming that being praised individually for their exceptional service, “leaves these others, in the hazardous state of being classed with those who are called the ‘vilest’” (12-13). Speculating about the “bad consequences” of this “partial relation of our conduct,” Jones and Allen again expand our incomplete historical frame, but this time towards the future, as they imagine a Black resident who served as a nurse during the epidemic being “abhorred, despised, and perhaps dismissed from employment” (10). In this vision of “some future day,” the problem is not only that Carey’s “partial relation” has served to “prejudice the minds of the people in general against us,” but that “it is impossible that one individual, can have knowledge of all” other individuals. Because no one individual can have knowledge of the whole, how the part is represented becomes lethally important. Jones and Allen’s single, definitive, copyrighted account of the yellow fever epidemic does not suggest that there’s no way of knowing the truth or that one partial account is as good as the next. Instead, Jones and Allen claim a kind of “power” from their own particularized “situation” to chronicle the material consequences and foreclosed possibilities of a historical record that is congealing before their very eyes (3).

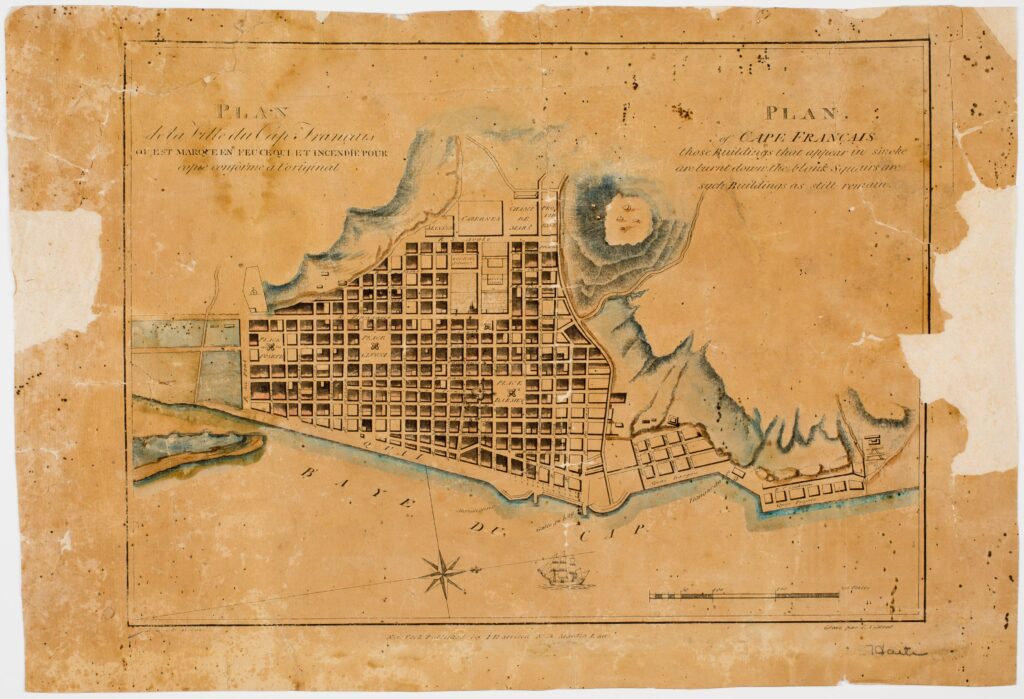

There is also an even more radical implication to Jones and Allen’s refusal to accept Carey’s partial praise: if virtue can be so easily misread as criminal, then insurgency can also be misread as contentment. Although Jones and Allen argue that any “alteration” made in the “hereafter” cannot “atone for the past,” they do suggest that imagining the future can impact the present (13). Rather than a sentimental futurism that defers action in the present to an ever-receding horizon, Jones and Allen claim that imagining future possibilities—possibilities of both equality and vengeance—should have an immediate effect on the present. While Jones and Allen firmly contrast the moral excellence of Black residents to the moral failure of white residents, they find Biblical precedent for considering “the contrary effects of liberty and slavery upon the mind of man,” and tell their readers “it is in our posterity enjoying the same privileges with your own, that you ought to look for better things” (24). But they also caution readers about their partial knowledge of what lies in the “hearts” of enslaved Black Americans: “We have shewn the cause of our incapacity, we will also shew why we appear contented; were we to attempt to plead with our masters, it would be deemed insolence, for which cause they appear as contented as they can in your fight, but the dreadful insurrections they have made, when opportunity has offered, is enough to convince a reasonable man, that great uneasiness and not contentment, is the inhabitant of their hearts” (25). Here surely “the dreadful insurrections” Jones and Allen refer to are in Haiti, a vision of a certain future for the United States should slavery not be ended in the immediate present, and a hyperlinked invocation of xenophobic associations between the contagion of fever and the contagion of insurrection. Collapsing geographic and temporal distance, this passage imagines Haiti’s past as America’s future.

This was not only the warning of a jeremiad, but also a reminder of the insurrectionary action that has already been taken by the enslaved and self-emancipated in the Atlantic world, and yet another recontextualization of that history as a just response, as a future to be anticipated rather than feared. The present perfect tense—“the dreadful insurrections they have made, when opportunity has offered”—and another seamless shift in pronouns from “our” to “they”—renders this history not so much a warning sign of a distant future to be averted as a proximate past that is catching up to the present. Just as readers can’t be sure where Haiti’s past-present ends and America’s future-present begins, they also can’t be sure of what lies beneath the “contented” appearances of Black Americans. Although the community Jones and Allen speak for privileges deliberation in the face of fear—the Narrative opens recounting that “we and a few others met and consulted how to act on so truly alarming and melancholy an occasion”—the Narrative also cautions against an expectation of a “superior good conduct,” of resiliency and mercy, that dissociates deliberation from “insurrections” (3, 23, 25).

Even as Jones and Allen contextualize the treatment of Black residents during the epidemic within a larger history of enslavement, oppression, and revolution, they also anchor the reader in the scene of immediate crisis by punctuating their narrative with the sights, sounds, and smells of the epidemic: “lunacy,” “ordure and other evacuations of the sick,” “vomiting blood, and screaming” (8, 9, 14). Their narrative forces the reader to experience the crisis as ongoing rather than complete. Jones and Allen do not use narrative to contain the disruptive effects of crisis, but to position those effects as part of an incomplete past and undetermined future. This theorizing of how to narrate crisis is what I have found so useful for thinking alongside Jones and Allen at a regional public university with students who are already well-equipped to recognize how unevenly the effects of crises accumulate across lives and institutions. By documenting the partial nature of the judgment that distinguishes between past and present, Jones and Allen empower students to see that perspective does not require detachment.

Further Reading

“The Blame Game: How Political Rhetoric Inflames Anti-Asian Scapegoating,” Stop AAPI Hate, October 2022.

Lauren Berlant, “Slow Death (Sovereignty, Obesity, Lateral Agency),” Critical Inquiry 33 (no. 3, Summer 2007): 754-80.

Joanna Brooks, American Lazarus: Religion and the Rise of African-American and Native American Literatures (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

Mathew Carey, A short account of the malignant fever, lately prevalent in Philadelphia: with a statement of the proceedings that took place on the subject in different parts of the United States (Philadelphia: Mathew Carey, 1793).

Mathew Carey, A short account of the malignant fever, lately prevalent in Philadelphia: with a statement of the proceedings that took place on the subject in different parts of the United States, 4th ed. (Philadelphia: Mathew Carey, 1794).

Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the Year 1793: And a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown Upon Them in Some Late Publications. By A.J. and R.A. (Philadelphia: William W. Woodward, 1794).

Stephen Knadler, “Narrating Slow Violence: Post-Reconstruction’s Necropolitics and Speculating beyond Liberal Antirace Fiction,” J19: The Journal of Nineteenth-Century Americanists 5 (no. 1, Spring 2017): 21-50.

Thomas Koenigs, “The ‘Mysterious Depths’ of Slave Interiority: Fiction and Intersubjective Knowledge in The Heroic Slave,” J19: The Journal of Nineteenth-Century Americanists 8 (no. 2, Fall 2020): 193-217.

Samuel Otter, Philadelphia Stories: America’s Literature of Race and Freedom (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

Derrick Spires, The Practice of Citizenship: Black Politics and Print Culture in the Early United States (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019).

Kyle Whyte, “Against Crisis Epistemology,” in Handbook of Critical Indigenous Studies, ed. Brendan Hokowhitu et al. (London and New York: Routledge, 2020).

Brandon W. Yan et al. “Death Toll of COVID-19 on Asian Americans: Disparities Revealed,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 36 (no. 11, 2021): 3545-49. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07003-0.

This article originally appeared in August 2023.

Laurel V. Hankins is Associate Professor of English & Communication at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, where she teaches and publishes work in early American literature. Her work can be found in African American Review, Legacy: A Journal of Women Writers, and Nineteenth-Century Literature.