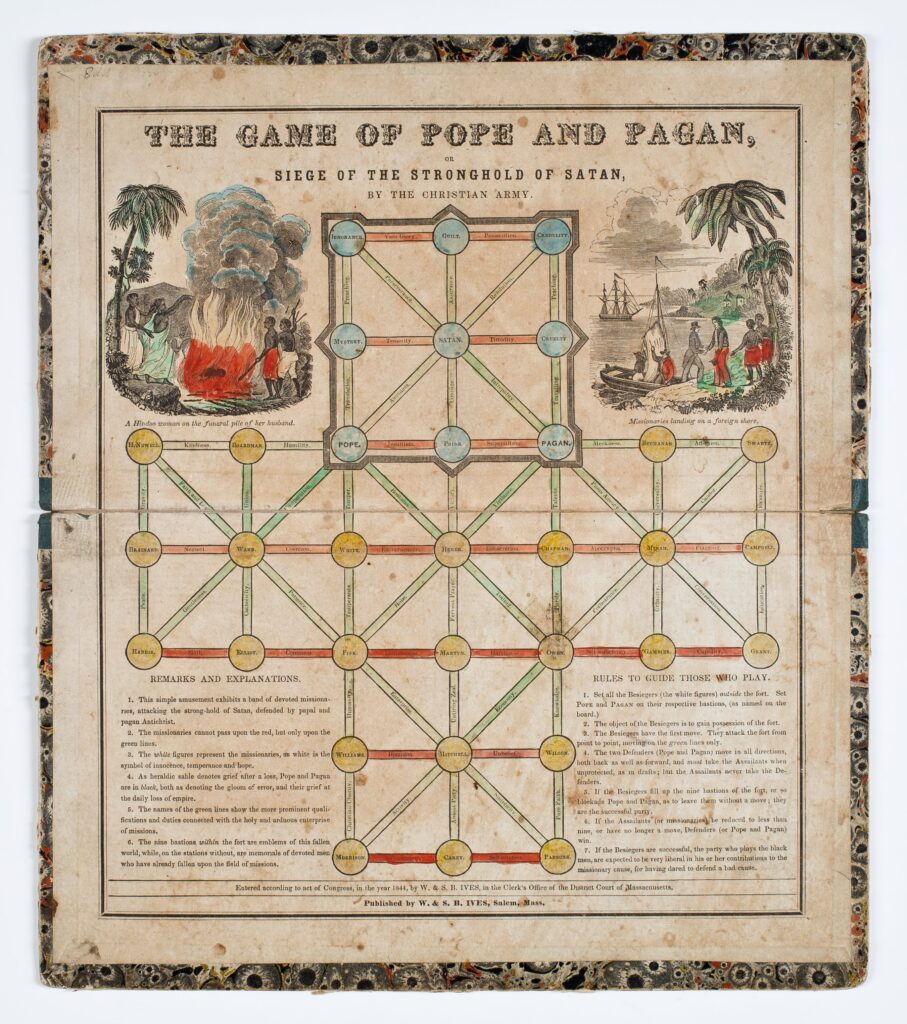

An astounding number of printed nineteenth-century games centered on Yankee peddlers. Early board game manufacturers tended to be publishers of children’s books. With titles like The Mansion of Happiness (1843) and The Game of Pope and Pagan or Siege of the Stronghold of Satan by the Christian Army (1844), games aimed to instill Christian morality. In 1848, W. & S. B. Ives produced The Yankee Trader, or the Laughable Game of What D’Ye Buy? Players selected a trade and related playing cards. A “conductor” then read a story, looking pointedly at players to fill in the blanks. Quick players contributed to the story akin to a card-directed Mad Lib. Too slow? Lose a card. McLoughlin Brothers published a similar game in 1850, as did Bunce & Brother in 1851 with Yankee Peddler: Or What Do You Buy?

The Peculiar Game of the Yankee Peddler—Or what do you buy?

Part of the utility of the game is how many intersections can be addressed, a Choose Your Own Adventure of lesson planning.

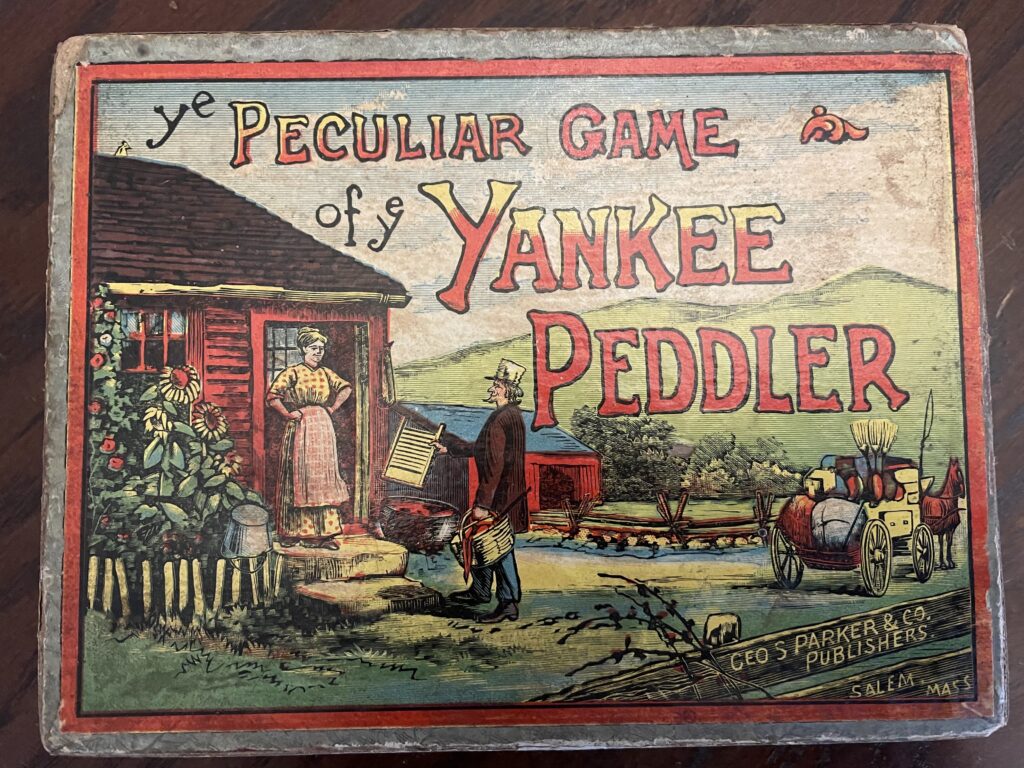

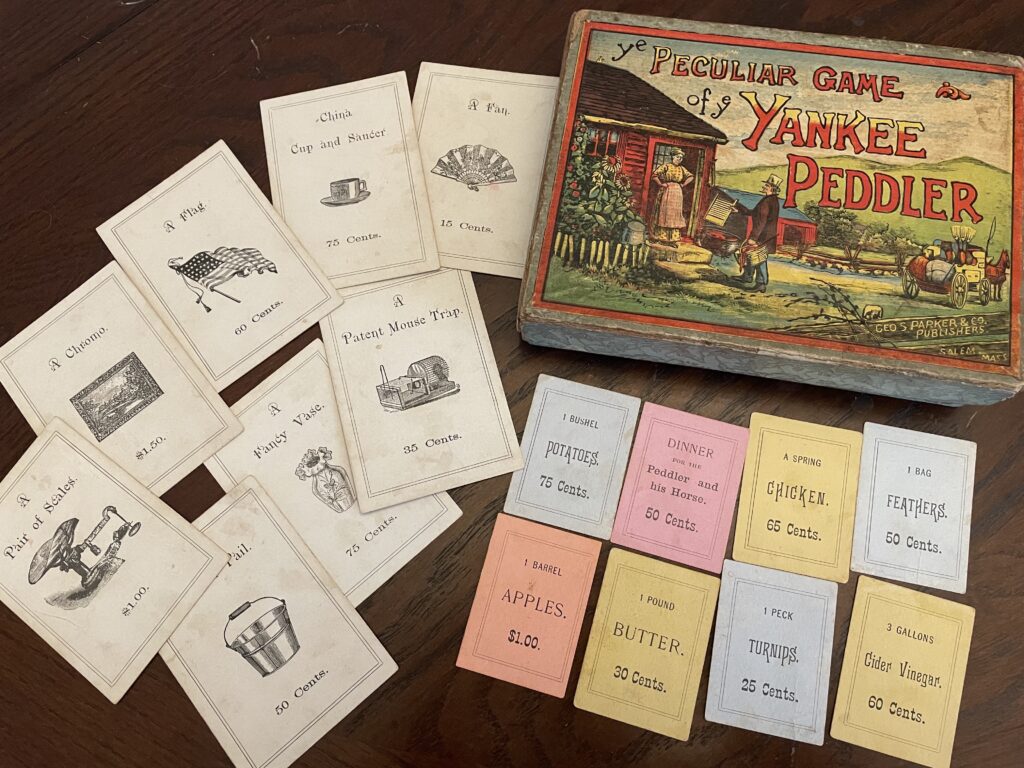

In 1888, George S. Parker & Co. created a new version, Ye Peculiar Game of Ye Yankee Peddler. Parker had invented his first game, Banking, in 1883 as a rejection of games as moral education. He preferred to emphasize a different value: competition. In Parker’s 1888 rendition, the Yankee Peddler served as gamemaster. The rules warned that the peddler should not be a player as he was favored to win. Instead, farmers competed against each other to get the best deals. The game below extrapolates from Parker to enliven lessons on the Market Revolution.

The game sets key historical dynamics in motion. How did distribution channels, including new transportation options, shape manufacturing and consumption? What did money look like and how did people spend it? When scholars discuss market anxieties of this age, what do they mean? This game offers a flexible format that allows students from middle school to college to jump in and actively contribute to the lesson.

Contextualizing the Game

In introducing the game, a variety of lessons can provide context: early industrialization, infrastructure, bankruptcy, banking and the Bank War, global trade, and American expansion and imperialism. But the game must start with the Yankee peddler. To David Jaffee, Yankee peddlers were more than distributors of goods, they were agents of capitalist enthusiasm. Largely young men in their early twenties, itinerant peddlers loaded up packs or wagons after the fall harvest and carried commodities to far-flung consumers. Local shopkeepers and regional factors advocated licensing laws to tax and stymie the competition. Nevertheless, these migrating merchants abounded through the 1850s. The US census counted 16,594 peddlers in 1860, most from New England, Pennsylvania, New York, and Ohio. They thus contributed to an increasingly integrated market economy. But peddlers were especially notable as cultural icons.

Yankee peddlers appeared in folklore as well as paintings, songs, and, of course, games. In Washington Irving’s classic tale Rip Van Winkle (1819), Mrs. Van Winkle died from a burst blood vessel. How? Arguing with a Yankee peddler. In one yarn shared in Constance O’Rourke’s American Humor, a Southern innkeeper clamors to see a “Yankee trick,” only to have the man sell his wife the coverlet off his bed. T. Jackson Lears writes that after the 1830s, with growing German Jewish immigration, the folkloric Yankee peddler intersected with antisemitic iconography. These tales fed into trickster lore of confidence men, from Herman Melville’s Confidence Man to Thomas Chandler Haliburton’s Sam Slick or even Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer, to the fantastic spectacles of P. T. Barnum.

Images of Yankee peddlers proliferated because they epitomized both the exuberance and the anxiety of the age. Board game covers and pieces can be found in collections held by the American Antiquarian Society, the New York Historical Society, the Strong Museum of National Play in Rochester, New York, and the Victoria & Albert Museum. Paintings include Asher Brown Durand’s The Peddler Displaying His Wares of 1836, The Yankee Peddler by William Tolman Carleton, circa 1851, John Whetten Ehninger’s 1853 Yankee Peddler, and Thomas Waterman Wood’s 1872 Yankee Pedlar.

Artistic representations of market transactions are themselves useful for discussions of social meanings of commerce. Gender, race, class, and regional identities are often visually striking in paintings and lithographs. Women gather round The Image Pedlar to examine shiny baubles in Francis William Edmonds’ circa 1844 painting. Lilly Martin Spencer modeled the adorably awkward 1854 Young Husband, First Marketing on her own husband. Comparing the two can spark a rich conversation about how society genders market agency. African Americans appear as subjects and objects, as bargainers, commodities, and status symbols. Art itself was a frequent medium of protest against slave dealing, as with Thomas Satterwhite Noble’s 1868 The Price of Blood.

“Yankee” itself is not always self-evident. For my California students, Yankees are either Union soldiers or New York baseball players. Norman Rockwell’s 1937 mural, Yankee Doodle, offers a familiar visual of the Revolutionary Yankee re-inscribing the lampooned “doodle” and proclaiming his feathered hat “macaroni.” Here, American Jonathan rebelled against older brother John (Britain). Globally, Yankee and Jonathan were interchangeable. Within the United States, however, the regionalism of the Yankee was important. This is perhaps best encapsulated in a poem attributed to E.B. White:

To foreigners, a Yankee is an American.

To Americans, a Yankee is a Northerner.

To Northerners, a Yankee is an Easterner.

To Easterners, a Yankee is a New Englander.

To New Englanders, a Yankee is a Vermonter.

And in Vermont, a Yankee is somebody who eats pie for breakfast.

The Yankee Doodle notwithstanding, Yankees were usually depicted as unassuming but clever, shading into unscrupulous. Yankee peddlers brought the message and the means for a farm family’s rise in status through conspicuous consumption. But peddlers tested a consumer’s mettle. The quality or value of goods was a question that might not have an answer until after the peddler was long gone. The family could rise in status, but they could also fall.

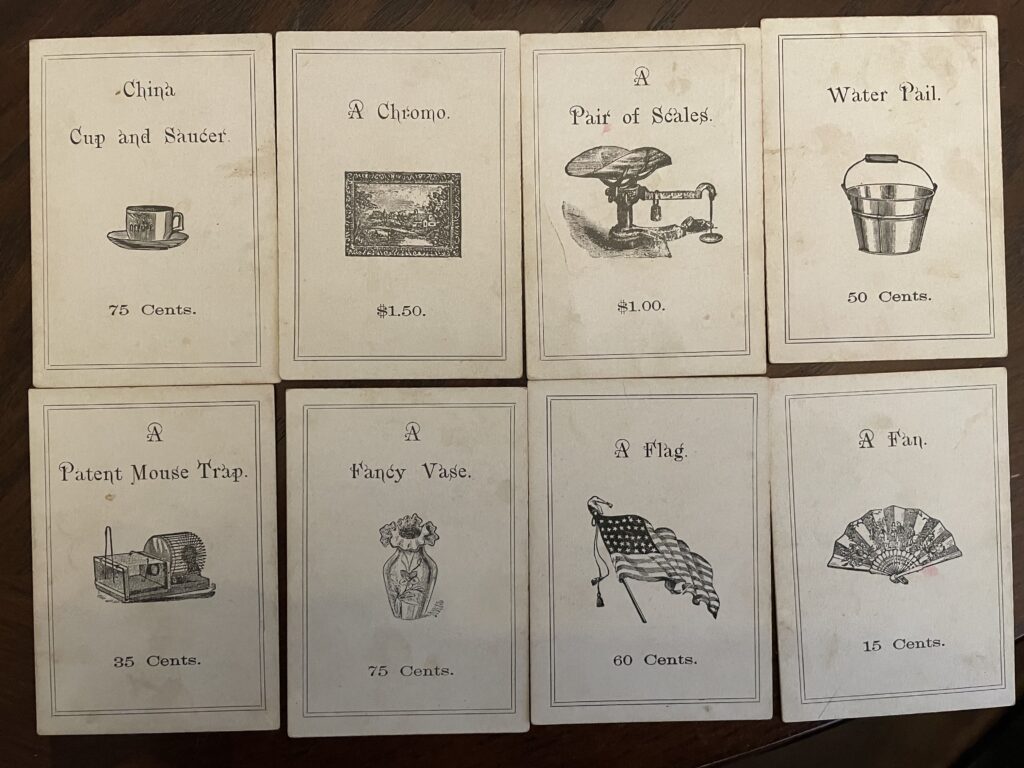

What did the new goods look like? In 1802, Eli Terry transformed the manufacturing of clocks. A stately grandfather clock signified craftsmanship and status for a family, but Terry used cutting saws, waterpower, and wooden parts to make the process faster and cheaper. By 1816, he produced a smaller version. Shelf clocks using the Terry method took the rural market by storm, sold via itinerant peddler distribution networks as signs of status. Innovations in publishing and lithographs enabled a wider variety of books and prints. Novels, biographies, and classics were popular, but perennial best sellers included bibles and almanacs. Peddlers themselves enabled publishers to diversify and even to distribute clandestine books like John Cleland’s Fanny Hill; or Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure.

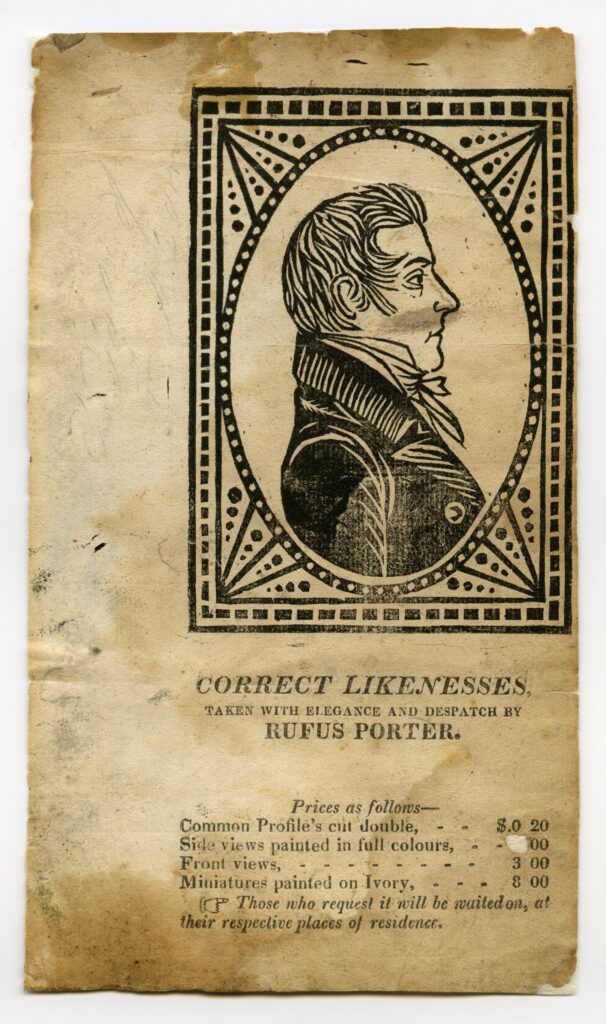

Portraits proved especially popular. Inventor Rufus Porter traveled New England selling silhouettes (black profiles) and quick portraits enabled by use of a camera obscura. A camera obscura used a dark box, lens, and mirror to cast a shadow that transformed portraits, like clocks, from luxury items to mass produced goods. This practice kicked up in the 1820s and by the 1830s, standardized “correct likenesses” found widespread buyers in hinterland communities. Peddlers brought the potential for renewal through news, fashion, and technology, with the goods to back it up—for a price.

Paper Money (is weird)

In practice, customers paid for goods with cash, bartered goods, or, for a higher price, credit. In the game, teams/families of students barter and buy using commodity cards and cash. Money merits explanation. In early America, money was complex. Colonial American efforts to rely solely on book credit (local vendors maintaining a running tab) combined with specie (silver) had never been terribly successful, as repeat efforts by British Parliament to crack down on colonial currencies testify. To have a commercial society, currency created liquidity that helped employers pay wages and consumers purchase goods and services. Cash facilitated market transactions and thus greased the economy.

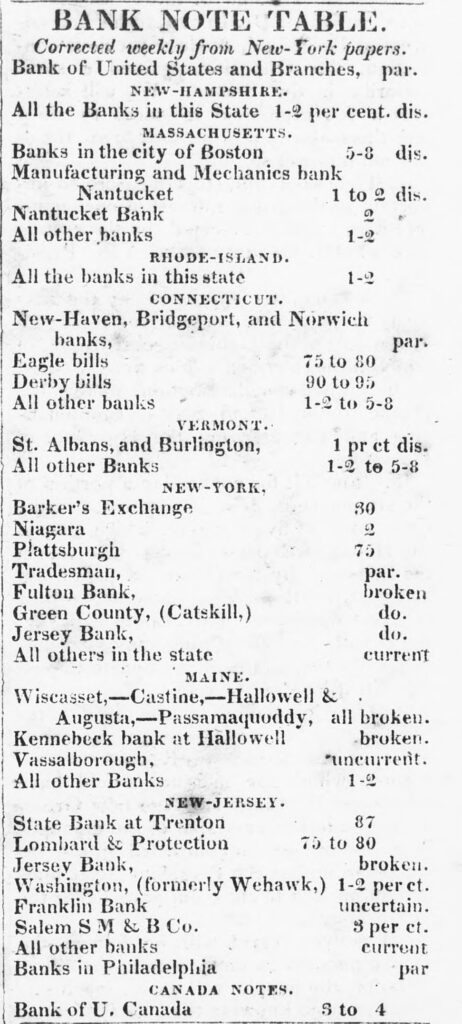

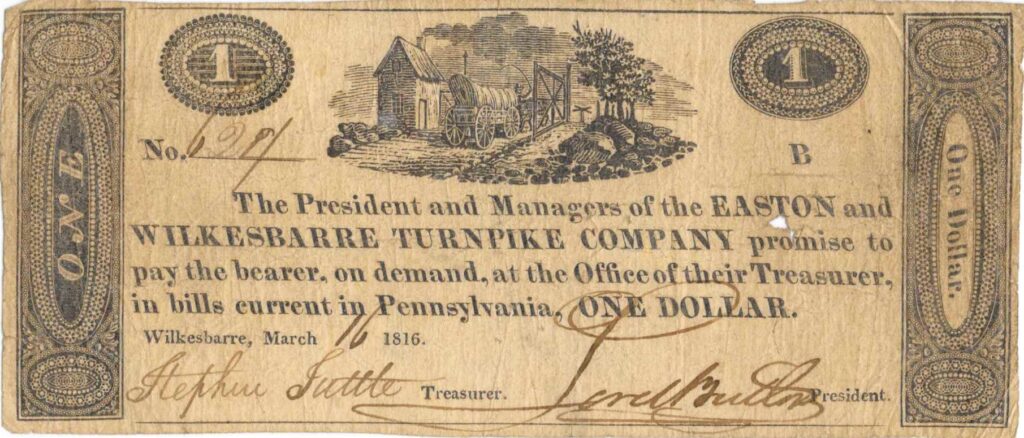

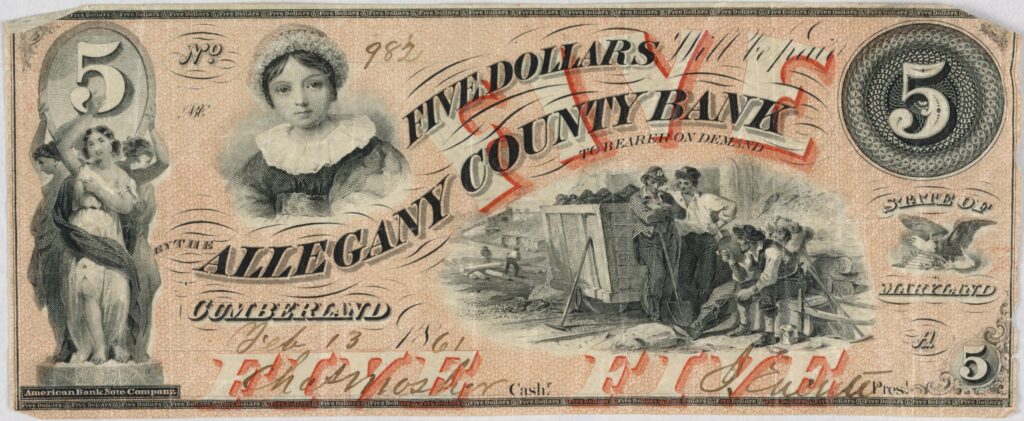

In the early US, the dollar was the legal unit of currency, but it was not a standard paper currency or legal tender designation until the Civil War. The First and Second Bank of the United States (BUS) printed bank notes and oversaw money markets, but they only provided a fraction of the nation’s currency supply. As Joshua Greenberg writes in Bank Notes and Shinplasters, at the height of its issue in the mid-1830s, the BUS only had $17 million in circulation at a time when the American economy was using approximately $100 million in paper currency. Where did the rest come from? It came from state-chartered banks and, also, non-bank institutions like private companies and hotels.

Market transactions in antebellum America required monetary literacy. New financial textbooks discussed paper currency, but described what goods should cost. They taught the federal monetary structure of dollars and cents. But the Bank of the United States provided the only currency accepted at face value, or par, throughout the country. Paper currency could be discounted based on perceived value, geographic circulation, or information gathered from bank note tables in newspapers. Peddlers themselves could benefit from arbitrage—carrying notes to markets where they might be exchanged more profitably. Using currency required savvy and experience. Newspapers carried stories of trial and error, from changing regulations and business upheaval to confidence men and counterfeiting. In one anecdote, a French tourist couldn’t pay a turnpike toll for his carriage because the 25 cent note he obtained from a steamship captain wasn’t good past the brook about 100 yards back.

The value of paper currency also depended on who wielded it. Being vulnerable left individuals open to exploitation. US Indian agents owed the Cherokee Nation $10,000, but the form of payment was left to the agents. Charles Hicks, Cherokee treasurer, recognized that accepting notes offered by Return J. Meigs meant a compromise in payment value, but had little recourse. This was not an isolated problem. Workers needed to pay attention to more than their stated wage, but also the form of wage. Some employers paid workers in out-of-town, devalued currency obtained from literal money markets because it cost them less and they had the power to get away with it.

Monetary literacy showed that you belonged in the marketplace on several levels. For escaped slaves to pass as free, familiarity with market transactions could prove vital. Women, despite savviness as consumers and retailers, were often depicted as spendthrift and easily bamboozled by flirty clerks. In Horatio Alger stories, being a keen consumer marked characters as worthy of rising from rags to riches. Ragged Dick, Or Street Life in New York with the Boot Blacks showcases Dick’s savvy recognition of the swindler shops of lower Manhattan. In The Peculiar Game of the Yankee Peddler, students face this very gamble. Are they worthy consumers?

Playing the Game

- Object: To get the best deals for your produce in market exchanges with the Yankee Peddler.

- Players:

- Yankee Peddler (the teacher) to oversee the auction.

- For large classes, a “clerk” or two might accept & tally the bids.

- Cluster students in “farm families” of 4-5 to decide upon their family’s bid for each item.

- Equipment:

- Playing Cards: Print all cards single-sided.

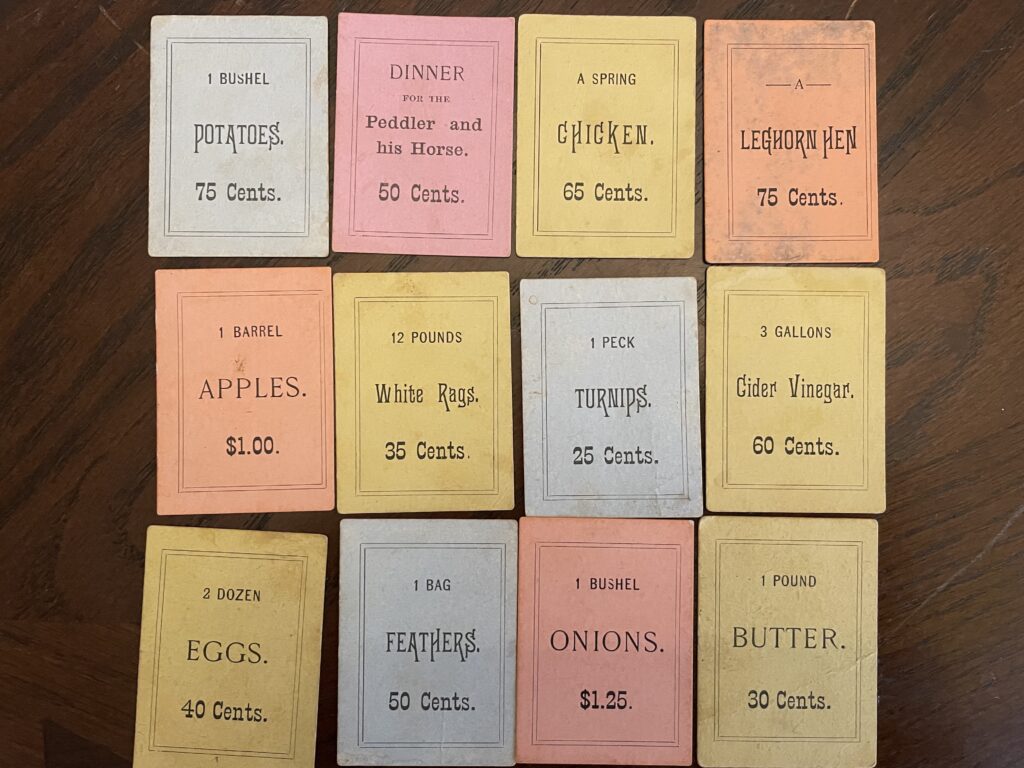

- Commodity Cards. These cards list an item of produce and a market value. Produce includes local crops or commodities: a bale of cotton, a bushel of potatoes or corn, a peck of turnips, a bag of feathers, a keg of whisky, dinner for the peddler and his horse.

- Bank Notes. Include a discussion of antebellum paper money with currency cards as well. Use images of antebellum currency with a discounted value underneath for each card. Make sure students understand the difference between par and discounted values before the bidding starts, but these visuals are great fun. If a group asks if you can provide change, rip a bill and return half.

- Bid Cards. Include as many bid cards as you have items so that families can submit a bid card for each item. The card should have a place to list family name and their bid.

- White or Chalk Board space to list items and purchasing family.

- Images of 6-8 commodities for purchase. Commodities might include Eli Terry clocks (~$6.75 cash, $8-9/credit), paintings ($.20 for a Rufus Porter likeness), books, a patented mouse trap, a scale, porcelain or ceramics, textiles like blankets, calicos, linens, and more. Create your own price list. The University of Missouri Library has a 19th century price guide by decade.

- Playing Cards: Print all cards single-sided.

- Game Play:

- Distribute cards to families, face down. All families should have the same number of commodity and cash cards (but not the same cards).

- The Yankee Peddler introduces himself, the number of items he has for sale, and the bidding process. He then introduces the first object. Sell it! As the Yankee Peddler, you want the highest price possible. Go ahead and give details about production, distribution, and social value of commodities. Do NOT reveal prices. Anxiety over how much the item is “worth” is a feature, not a bug, of the game.

- Families submit bids, face down.

- After collecting all bids, the family who has submitted the highest bid buys the item. The peddler can refuse to sell an item. Students often bid very low at the beginning and then very high toward the end of the game.

- To Win: when all commodities have been sold, tally up a final profit and loss for the peddler. Which family got the best deals for their produce relative to the cost? That family wins the game.

Conclusion

In drawing the game to a close, circle back to the discussions of market-based anxieties.

How do you know if you got a good deal? How do you know how much an item was “worth”?

What shapes prices? Is it just supply and demand? Is it the costs to bring an item to market? Discussing the social value of the goods and what went into their own evaluation of their bidding process can be worthwhile. How did competition shape the game? How might it have played out differently with open bidding? Do these capitalist market transactions feel like gambling?

Many other subjects can be incorporated into the game or its surrounding lesson plan. I started this game for my History of US Capitalism course, with a day on the reorganization of labor, industrialization, and child labor and another on banking controversies. I include yarns that reveal the “Yankee peddler” to be a global figure and connect him to foreign trade. Part of the utility of the game is how many intersections can be addressed, a Choose Your Own Adventure of lesson planning. Find any favorites in your own classroom? Please share!

Further Reading

On the history of game production, see Philip Orbanes, The Game Makers: The Story of Parker Brothers, from Tiddledy Winks to Trivial Pursuit (Cambridge: Harvard Business Review Press, 2003). On a provocative essay on those earlier games and morality, see introduction of Jill Lepore, Mansion of Happiness: A History of Life and Death (New York: Knopf, 2012).

While textbooks still frequently refer to the Market Revolution, rooted in books like Charles Sellers, The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815-1846 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), this game is not contingent upon that concept. More recent work, like Jonathan Levy’s Ages of American Capitalism: A History of the United States (New York: Penguin Random House, 2021) and Eli Cook, The Pricing of Progress: Economic Indicators and the Capitalization of American Life (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017) favor a focus on infrastructure per George Taylor, The Transportation Revolution, 1815-1860 (New York: Rinehart and Company, 1951).

On Yankee peddlers, see David Jaffee, A New Nation of Goods: The Material Culture of Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010) and “Peddlers of Progress and the Transformation of the Rural North, 1760-1860,” Journal of American History 78 (Sept. 1991): 511-35; Joseph T. Rainer, “The ‘Sharper’ Image: Yankee Peddlers, Southern Consumers, and the Market Revolution,” Business and Economic History 26 (Fall 1997): 27-44; T. Jackson Lears, Fables of Abundance: A Cultural History of Advertising in America (New York: Basic Books, 1994); J. R. Dolan, The Yankee Peddlers of Early America: An Affectionate History of Life and Commerce in the Developing Colonies and the Early Republic (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1964). For more on folklore, see Constance Rourke, American Humor: A Study of the National Character (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1931) and Chaim M. Rosenberg, Yankee Colonies Across America: Cities upon the Hills (New York: Lexington Books, 2015). For art history, see Terrence H. Witkowski, “Farmers Bargaining: Buying and Selling as a Subject in American Genre Painting, 1835-1868,” Journal of Macromarketing 16 (no. 2, 1996): 84-101.

A few classic works on capitalism as a game, see Ann Fabian, Card Sharps and Bucket Shops: Gambling in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Routledge, 1999); Jane Kamensky, The Exchange Artist: A Tale of High-Flying Speculation and America’s First Banking Collapse (New York: Viking, 2008); Karen Haltunnen, Confidence Men and Painted Ladies: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America, 1830-1870 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1982); Scott A. Sandage, Born Losers: A History of Failure in America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009).

On the history of money, see Joshua Greenberg, Bank Notes & Shinplasters: The Rage for Paper Money in the Early Republic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020); John McCusker, Money and Exchange in Europe and America, 1680-1775: A Handbook (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992).

On the global Yankee trader, see, for example, Jonathan Eacott, Selling Empire: India and the Making of Britain and America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016); Kariann Yokota, Unbecoming British: How Revolutionary America Became a Postcolonial Nation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); James Fichter, So Great a Profitt: How the East Indies Trade Transformed Anglo-American Capitalism (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010); Susan Bean, Yankee India: American Commercial and Cultural Encounters with India in the Age of Sail, 1784-1860 (Salem, Mass.: Peabody Essex Museum, 2001).

This article originally appeared in July 2023.

Rachel Tamar Van teaches early American history, the history of US capitalism, and family and genealogical history at Cal Poly Pomona in southern California. She has articles you might use to expand on the US China trade in Diplomatic History, the Pacific Historical Review, and the Routledge History of US Foreign Relations.