Haveman’s Magazines and the Making of America is a study in cultural sociology that explores the history of a print medium that flourished in the nineteenth century and beyond. Unlike a historian, the sociologist Haveman does not primarily seek to explain why magazines and their readers followed various paths. Instead the author aims to demonstrate that magazines promoted the creation of imagined, translocal communities. By assembling data on the chronology of the founding and survival of magazines, and by analyzing the specific places, urban and rural, where they were produced as well as their topical specialties, Haveman provides a significant contribution to scholarship on the early history of periodicals in the United States. Her primary audience is sociologists, but historians of printing, newspapers, the book, and of reading will find Magazines and the Making of America instructive.

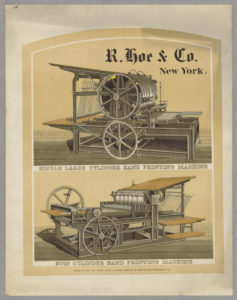

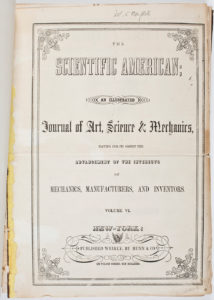

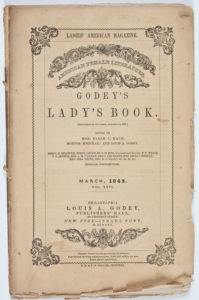

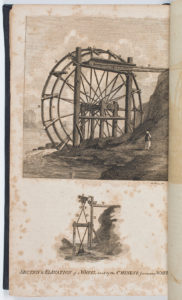

The study is divided into eight chapters. The introduction explains that, since newspapers and books have been much studied, magazines warrant fresh analysis that will enable readers to understand “the modernization of America.” Haveman’s second chapter sketches the chronology of American magazines from their fragile eighteenth-century beginnings, when they catered to the gentry, to the next century when magazines multiplied dramatically and came to serve far broader audiences. Chapter three provides a brief history of specific changes in the United States that encouraged magazines to flourish: the emergence of industrial printing, postal expansion and subsidies, the growth of literacy and the education industry, copyright protection, and the commercialization of authorship. Haveman’s fourth chapter treats the who, why, and how of magazine founding. Though first started by printers and gentlemen in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, by the 1820s magazines were being created in many locations, both by entrepreneurs to gain profits and by organizations to support their missions.

The author turns next to the proliferation of specific types of magazines. In separate chapters treating religious, social reform, and economy-related magazines—covering topics as diverse as agriculture, foreign missions, fraudulent currency, and scientific technology—she charts the broad reach of these periodicals. In a concluding chapter Haveman argues that evidence drawn from magazine history revises the conclusions of classic sociologists such as Emile Durkheim and Karl Deutsch in key ways. “The communities supported by magazines,” such as Sabbatarians, “could be simultaneously modern and antimodern” (272). By studying the development of this once new medium across time, she argues, we can better understand new media today. As she puts it, magazines were “both causes and consequences of fundamental shifts in American culture” (273).

Haveman’s book is primarily a study of production and, to a lesser extent, distribution. She does not address why Americans sought to be informed or why legislatures approved public policies that promoted information systems such as political parties and the U.S. post office. Because of this focus, the book’s contribution to our understanding of the formation and extent of translocal communities, both imagined communities of similarly disposed individuals as well as formally organized voluntary associations, is more doubtful. For instance, she does not investigate their cultural foundations in ideology, social structure, or practice. Likewise, she makes little effort to explain the actual reception of periodicals or how their content differed from or overlapped with that of newspapers. The creation of a translocal community, therefore, is asserted but not actually demonstrated. Haveman’s evidence does not describe whether and how subscribers and readers interacted with each other. The closest the author comes to considering reader response is to quote readers’ letters—authentic or not—to magazines, where readers supplied admiring testimonials to the usefulness of the publication. No private letter, no diary, no report of a conversation illumines how the contents of any particular magazine affected the way any person thought about their actual local or imagined translocal community. In like manner, county, statewide, and national meetings and conventions, where translocal communities were embodied in face-to-face encounters, are omitted from consideration. Instead the author uses the statistics of circulation and organization membership to infer the reality of translocal communities composed of reformers like abolitionists or denominations such as Methodists. This is persuasive up to a point, but for historians this is not new.

Much of the author’s discussion, derived as it is from historical scholarship of the past two generations, will be familiar to historians of the subject. Sometimes, as with Haveman’s account of ideas concerning intellectual property and the payment of authors, her treatment is attentive to the most recent scholarship; elsewhere, such as the coverage of education and literacy, it seems dated. And on occasion well-known information, such as the dramatic increase in urban growth, is presented at length. Perhaps in consequence, readers encounter generalizations so time-worn as to be banal, as when Haveman repeats a conclusion by Arthur Schlesinger Sr., provided nearly a century ago: “Urbanization fundamentally altered the nature of social life in America” (78).

The author has read widely in American historical scholarship and is generally well informed. Yet there are some puzzling omissions. The past generation’s work on the history of the book and the nature of reading practices, including William J. Gilmore’s Reading Becomes a Necessity of Life: Material Cultural Life in Rural New England, 1780-1835 (1992) and capped by the five-volume History of the Book in America (2007-10), evidently escaped the author’s notice. Admittedly this scholarship does not focus on magazines especially, but if one is to understand magazines’ place in American communication patterns, it is vital to consider them in the context of reading practices and within the broader range of communication systems, oral as well as printed.

Haveman’s apparent unawareness of key authors within this body of work, such as Robert A. Gross, David D. Hall, and Mary Kelley, is especially surprising since she does cite Richard B. Kielbowicz, News in the Mail: The Press, Post Office, and Public Information, 1700-1860s (1989), David Paul Nord’s Communities of Journalism: A History of American Newspapers and their Readers (2001), Nord’s Faith in Reading: Religious Publishing and the Birth of Mass Media in America (2004), and Ronald J. Zboray’s A Fictive People: Antebellum Economic Development and the American Reading Public (1993).

These gaps in what is evidently a thoroughly researched work are likely a consequence of an author working across disciplines. For cultural sociologists, Haveman’s historical recounting of American economy and society may prove fresh and informative. Moreover for historians, Haveman’s forty-one graphs and twenty-seven tables, together with her carefully explained methods of data collection and analysis—laid out in two appendices—can seem like overkill in this post-quantitative era of historical scholarship. Inasmuch as Haveman is seeking to establish objectively verifiable generalizations about when, where, and how magazines succeeded and failed, the data and her methods are crucial for sociologists. For historians who may be skeptical of the accuracy and reliability of nineteenth-century circulation data, the methodological explanation may be less important.

Whenever a scholar in one discipline crosses disciplinary boundaries, s/he risks running afoul of the expectations of some parts of the audience. As the preceding comments demonstrate, Haveman, as a sociologist, has here encountered an “outsider” critique. But historians as well as sociologists should admire and learn from Magazines and the Making of America. It provides the most sophisticated analysis of magazine founding that exists thus far, and it offers an interpretation of the cultural importance of magazines that warrants serious consideration. Moreover Haveman’s attention to the formation of translocal communities as a key part of the modernization process warms the heart of this critic, who long ago made that argument in Modernization: The Transformation of American Life, 1600-1865 (1976). Inasmuch as Haveman quotes that old work, this reviewer, flattered, might be said to tilt in the author’s favor.