On Finding the Earliest Known Poem by John Rollin Ridge, the First Native American Novelist

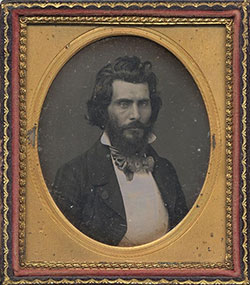

I sometimes think that I could recognize John Rollin Ridge’s voice anywhere. Considering he died in 1867—a widely hated California Copperhead newspaper editor, and the exiled scion of a once-powerful Cherokee family—this feeling is a bit uncanny. But, as many readers of Common-place can probably attest, spending a great deal of time with the work of a particular writer has the effect of rendering him familiar as an old friend. One grows accustomed to his repeated patterns of thought, his recurring metaphors, until finally one is able to recognize the writer’s voice as easily as that of a remembered classmate heard from across a crowded room. And it was this voice—by turns bombastic and anxious, deeply Christian and yet infused with the rhetoric of Romantic transcendence—that I recognized while flipping through a copy of the Arkansas State Gazette in the American Antiquarian Society’s reading room last January.

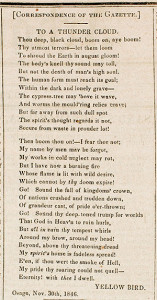

If John Rollin Ridge is familiar at all today, it is likely as the author of The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta, the first novel written by a Native American. Yet Ridge was a journalist for most of his career, and wrote throughout his life. I was visiting AAS to research Ridge’s California newspaper editorials from the 1850s for a dissertation chapter dealing with Mexican resistance in California after the Mexican-American War. On a lark, I thought I might take a look at a few of the local newspapers from places where Ridge lived during his teenage years. I didn’t expect to find much, but there it was: a previously unknown poem by a very young John Rollin Ridge, titled “To a Thunder Cloud.” It was even signed with Ridge’s pen name, Yellow Bird—an English translation of his Cherokee name, Cheesquatalawny. Even without the byline, though, I would have recognized that voice—dramatic, sing-song, redolent of violence—just about anywhere.

What was more, the poem appeared to be Ridge’s earliest extant publication. Appended to the text was a composition date of November 1846, when Ridge was only nineteen. That date was earlier than any other known Ridge poem, including those that exist only in manuscript form. Scholars have had a hazy awareness that Ridge wrote poetry as a young man (biographer James W. Parins refers to, but does not identify, “several … poems, published under the pen name Yellowbird”), but much of this writing remains undiscovered. His earliest identified poem, “To a Mockingbird,” was composed in May 1847, seven months after the composition of “To a Thunder Cloud,” and not published until years later.

Much of this early poetry strikes readers as derivative and unconnected to Ridge’s later complex politics. Take “Mockingbird,” for example. The speaker of this poem addresses the bird of the title, which sits on a high perch. Below, human beings suffer. Above, the bird watches. Does the bird empathize with suffering people, the speaker wants to know, or does it instead exist in an immortal realm of “living thought,” far removed from human concerns? Considering that another name for the Northern Mockingbird is the American Nightingale, it is perhaps unsurprising that the poem is reminiscent of John Keats’s more famous ode, which also links birdsong to immortality. But Ridge’s “Thunder Cloud,” it seemed, was inflected by the politics of the moment, and in ways that revealed the political dimensions of his other poems, like “Mockingbird.” In order to explain, I’ll have to back up.

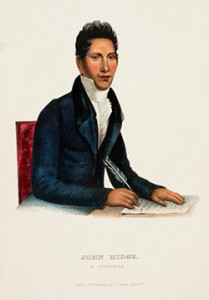

Although Ridge was occasionally composing poems in a Romantic mode by 1847, writing had not been his primary concern. The twenty-year-old’s life had been lived at the center of a political maelstrom. At the age of twelve he watched a gang of assassins brutally murder his father just outside the family home. This murder was the culmination of a conflict that had gone on for nearly a decade. Just prior to the elder Ridge’s death, there had been two Cherokee nations—one bordering Georgia and another just across the western border of Arkansas. The state government of Georgia, however, coveted the lands of the eastern Cherokee nation. White settlers had, over the years, attempted to seize portions of it. This resulted in a power struggle within the eastern Cherokee nation itself. On one side stood the Ridge family and their allies, who believed the eastern nation would eventually be lost and therefore supported a plan to sell it entirely in exchange for millions of dollars and lands in the West. Some compensation for this loss, they reasoned, would be better than nothing. On the other side were the supporters of John Ross, who wanted to stay and fight for their ancient rights.

In 1835, Rollin Ridge’s father, John Ridge, signed the Treaty of New Echota, selling the entire eastern Cherokee nation in exchange for lands in the West and financial compensation to be distributed among the Cherokee people. This led to the infamous 1838 Trail of Tears—the militarily enforced expulsion of the Cherokee people from their nation in the east. Thousands died. From John Ridge’s perspective, removal was the only option. He once compared it to the Exodus: a long march from slavery to freedom. But to John Ridge’s enemies, the treaty and removal constituted a betrayal. And so, in 1839, supporters of John Ross surrounded the Ridge family’s new settlement at Honey Creek, in the western Cherokee nation. They dragged John Ridge from his home and stabbed him twenty-nine times, killing him. Fearing for their lives, the surviving members of the Ridge household left for Arkansas a week later.

The conflict within the Cherokee nation continued during John Rollin Ridge’s teenage years, which he spent exiled in Arkansas. By 1845, the long-simmering feud between the “Treaty Party” (as the Ridge family and their allies came to be known) and the more powerful John Ross faction had broken out into widespread, sectarian violence. Ridge’s biographer, James W. Parins, writes that we simply cannot know the degree to which the teenage John Rollin Ridge participated in or was affected by the violence marking this period of his life. What is clear, however, is that he wanted to be involved in some way. Ridge formed inchoate plans to murder John Ross. He wrote a letter to a cousin asking for a Bowie knife. He praised the guerrilla tactics of an anti-Ross fighter. When the United States government brokered a peaceful settlement to the violence in 1846, and ratified this settlement in August of that year, it marked an end, at least temporarily, to the fighting. But Ridge’s letters from this period suggest that his mission to restore his family’s position—and not his goal of becoming a poet and author—remained foremost in his mind.

And this restoration was precisely what Ridge set about accomplishing. He received reparations for his father’s murder, as specified by the August 1846 treaty. He purchased the family farm at Honey Creek, near the Cherokee-Missouri border, which his mother had been forced to flee with her children nearly eight years before. And, in May 1847—the same month he wrote “To a Mockingbird”—Ridge married Elizabeth Wilson.

But the Cherokee nation was still riven by conflict. In 1849 Ridge murdered David Kell, a pro-Ross judge. (There is some evidence that Kell stole one of Ridge’s stallions and castrated it in order to provoke a fight that would enable him to justifiably murder the heir-apparent to a marginalized but still threatening political faction. If this was Kell’s plan, it proved to be something less than a complete success.) After this, the young poet was forced into exile, first in Missouri and then in California. It was then that he began to write professionally. At first he published articles about the California Gold Rush in newspapers and periodicals. Then, in 1854, Ridge published his first and only novel, The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta, a bacchanal of political violence set in U.S.-controlled California.

Or so goes the conventional account of Ridge’s writing. But the text before me pushed the timeline of Ridge’s authorship back by nearly a year. The poem I had encountered in the Arkansas State Gazette, “To a Thunder Cloud,” had been published on January 9, 1847. More importantly, it was dated November 30, 1846. I was looking at an example of Ridge’s poetry written not around the time of his marriage, but much earlier—only a few months after the U.S.-government brokered settlement between warring Cherokee factions.

And the poem was written in that recognizably bombastic Ridge style. Organized into two stanzas, made up of four and six tercets, respectively, the poem reveals a steely-eyed speaker unafraid of violence, death, or upheaval. Ridge begins by addressing the thunder cloud of the title:

Thou deep, black cloud, boom on, aye boom!

Thy utmost terrors—let them loom

To shroud the Earth in august gloom!

The body’s knell thy sound may toll,

But not the death of man’s high soul.

The speaker’s address offers a challenge to a malevolent natural order. Even the weather in the world of Ridge’s poem is dangerous, looming overhead with its “utmost terrors,” shrouding “the Earth in august gloom,” and tolling a grim, funereal knell. From any other nineteen-year-old poet, we might read the talk of death as merely imitative Romanticism—all that chiaroscuro, those picturesque shades of darkness and light. And yet Ridge’s early life had been defined by violence: the death of his father, the sectarian bloodshed in the Cherokee nation, and the senseless brutality of the Arkansas frontier, where, Ridge once wrote to an acquaintance, “the people sometimes fight with knives and pistols, and some men have been killed here, but the people do not seem to mind it much.”

And yet the text isn’t only inflected with Ridge’s violent past. It is also heavily invested in a transcendent individuality. In addressing the thunder, the poem valorizes the unique power of an individual to confront a terrifying natural order. Ridge begins the second stanza:

Then boom thou on!—I fear thee not;

My name by men may be forgot,

My works in cold neglect may rot,

But I have now a burning fire

Whose flame is lit with wild desire,

Which cannot by thy doom expire!

Go! Sound the fall of kingdoms’ crown,

Of nations crushed and trodden down,

Of grandeur cast, of pride o’er-thrown;

Go! Sound thy deep-toned trump for worlds

That God in Heav’n to ruin hurls,

But all in vain thy tempest whirls

Around my brow, around my head!

Beyond, above thy threatening dread

My spirit’s home is fadeless spread!

There’s a lot here. Ridge’s speaker resolves to accept the vicissitudes of fortune, and yet this acceptance is a screen for his defiance. Yes, he suggests, history may forget him and his works—all that as-yet-unwritten literature. But, despite this, he will struggle on. Ridge’s writing career would in fact be consumed by considerations of doomed struggle, particularly in the form of revolutionary bloodshed. His novel, The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta, considers a band of Mexican war veterans who wage a brutal conflict with white Americans, including U.S. soldiers. And Ridge’s newspaper editorials, written in later years, equivocate about the U.S. Civil War by nominally defending the Union but nonetheless heaping criticism on President Lincoln and acknowledging the South’s right of rebellion. The revolutionary perspective that defines these later texts is radically articulated even here, in a sing-song poem Ridge wrote when he was still a teenager. Acts of resistance, he suggests, are not to be measured by their potential for success. Kingdoms fall. Nations are crushed. And powerful factions—with their “grandeur” and their “pride”—are usurped. But the poem’s speaker remains undaunted. Victory is less important, in this worldview, than fearlessness.

But, perhaps most interestingly, the poem offers a pair of interwoven beliefs animating this fearlessness. It ultimately argues that these powerful, natural forces remain ineffectual because a Christian God holds out a redemptive promise of salvation and grace. This perspective would remain with Ridge throughout much of his writing career, although it appears in no more than a few traces in his novel. But lurking behind this conventional message of Christian salvation is a veneration of the individual. Ridge’s poem is brash in its defiance of impossible odds. He writes: “E’en, if thou wert the smoke of Hell, | My pride thy roaring could not quell—.” And while he ends on a final note of salvation (“Eternity! with thee I dwell”), the poet nonetheless has given us a speaker who fears nothing—not the natural world, not the fall of nations, not “the smoke of Hell” itself. Ostensibly, it is his faith in salvation that gives him this strength—it is the “Eternity” of the final line. And yet, in the preceding line, Ridge provides another explanation: “pride,” which the thunder’s “roaring could not quell.” The speaker finds strength both in his faith and, more blasphemously, in his own pridefulness.

Ridge’s poem, one might suspect, articulates his ambivalence about the new political order. It could also serve as a message to his enemies that he does not fear them.

Coming just a few short months after a treaty ostensibly settling the differences between warring Cherokee factions, Ridge’s poem, one might suspect, articulates his ambivalence about the new political order. It could also serve as a message to his enemies that he does not fear them. In late 1846 and early 1847, Ridge was putting into motion his return to the Cherokee nation: collecting reparations, re-purchasing the family settlement, moving into his family’s former home. Dated in late 1846, then, the poem becomes extraordinarily suggestive. If the poet does not fear the “smoke of Hell,” it is unlikely that he fears John Ross.

Ridge never stopped writing poetry. Yet during his lifetime he was known more as a Democratic newspaper editor than as a literary figure. Even his brief attempt to fashion himself as a novelist failed financially. After his death, his widow arranged for the publication of his collected poems. In an unsigned Preface, possibly written by Elizabeth Wilson Ridge herself, we learn that “Mr. Ridge lost in the excitement of political life his youthful ambition for literary fame.” The posthumous collection was an attempt to restore Ridge’s significance as a poet (the praise of the “Eastern … press” gets a mention), as well as to generate money for his widow. Interestingly, though, the collection does not include “To a Thunder Cloud,” either because the poem was lost or because it did not conform to the apolitical, literary version of John Rollin Ridge put forward by the preface.

The collection sold poorly, in any case, and Ridge was largely forgotten for over a century. In a 1979 article in MELUS, Thomas King identified Ridge’s Joaquín Murieta as the first novel by a Native American writer, and in 1990 Ridge’s writing was included in the Heath Anthology of American Literature. After that, interest in Ridge developed in more significant ways. Today, scholars like John Carlos Rowe and Mark Rifkin have done excellent work on Ridge, particularly in reconsidering his first and only novel. Despite this, there is much more to do. No complete scholarly collection of Ridge’s writing exists, and most of his prose remains scattered in nineteenth-century newspapers and periodicals from Arkansas to Texas to California, many of them un-digitized. For nearly a century, Ridge’s prediction that his “works in cold neglect may rot” seemed to have come to pass. Now, however, his voice—in all its bombast—is re-emerging.

Further Reading

While Ridge’s complete writings are not yet collected, his novel and many of the articles and poems he wrote throughout his life are available in print. See John Rollin Ridge, The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta, the Celebrated California Bandit, ed. Joseph Henry Jackson (Norman, Okla., 1955); John Rollin Ridge, Poems (San Francisco, 1868); John Rollin Ridge, A Trumpet of Our Own: Yellow Bird’s Essays on the North American Indian, eds. David Farmer and Rennard Strickland (San Francisco, 1981); and Edward Everett Dale and Gaston Litton, eds.Cherokee Cavaliers: Forty Years of Cherokee History as Told in the Correspondence of the Ridge-Watie-Boudinot Family, (Norman, Okla., and London, 1995).

The original manuscript of Ridge’s “To a Mockingbird” is housed in the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. A published version can be found in Ridge’s posthumous collection, Poems, from 1868. For the poem considered at length here, see Yellow Bird, “To a Thunder Cloud,” Arkansas State Gazette 9:2 (January 1847).

For a biography of Ridge, see James W. Parins, John Rollin Ridge: His Life and Works. (Lincoln, Neb., and London, 2004).

For the establishment of Ridge as the first Native American novelist, see Thomas King, “Additions to ‘A Bibliography of Native Novels.'” MELUS 6:4 (1979): 79.

For recent scholarship on Ridge, see especially John Carlos Rowe, “Highway Robbery: ‘Indian Removal,’ the Mexican-American War, and American Identity in The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta,” NOVEL 31:2 (1998): 149-173; Jesse Alemán, “Assimilation and the Decapitated Body Politic in The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta,” Arizona Quarterly 60:1 (2004): 71-98; and Mark Rifkin, “For the wrongs of our poor bleeding country’: Sensation, Class, and Empire in Ridge’s Joaquín Murieta,” Arizona Quarterly 65:2 (2009): 27-56.

This article originally appeared in issue 14.4 (Summer, 2014).

Gordon Fraser is a PhD candidate in English at the University of Connecticut. Last January, he held a Jay and Deborah Last Fellowship at the American Antiquarian Society. His scholarship has appeared in NOVEL, J19: The Journal of Nineteenth-Century Americanists, The Henry James Review, and Victorian Literature and Culture. His dissertation, “American Cosmologies: Race and Revolution in the Nineteenth Century,” deals with the literatures of revolutionary violence across the long nineteenth century, from Black Nationalism to Cherokee Nationalism to the Hawaiian independence movement. He is currently a Draper Dissertation Fellow at the University of Connecticut Humanities Institute.