Memory gives rise to rites of observance only when the event speaks to the future.

How does one create memory around an event that has long been lost to history? How to celebrate the sesquicentennial of the end of the Civil War in the city most responsible for secession? How does one coalesce memory around an event that has been repressed or dissipated?

The surrender of Charleston was not an event memorialized by the city’s white or black citizens during the subsequent century and a half. The repression of the memory of defeat, failure, the loss of a generation of young men is perhaps all too understandable for those white families who have lived long in the land. For the newly liberated African American population, the day of the enactment of the Emancipation Proclamation was a day of jubilee, celebrated with parades and picnics until these rites were in turn repressed by the Charleston municipal government in the 1880s. Thereafter the oppressions of Jim Crow throughout the South made it seem that not much had been won worth celebrating after all.

These ruminations on rites of memory and the end of the Civil War would not have occurred to me if I had not, in the course of studying the history of Lowcountry foodways, discovered an event that made me look closely at the scene in the defeated city of Charleston in the two months following its surrender.

Charleston, 1865: A Feast for A City Divided

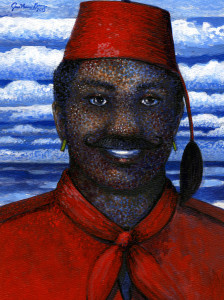

Charleston, S.C., the hotbed of secession, surrendered to Union Forces on February 18, 1865. The Union Army’s occupation liberated the approximately 10,000 slaves who remained in the city. Among them was the Lowcountry’s greatest chef and restaurateur, Nat Fuller, who had spent most of his life as a slave (1812-1866). On February 22, 1865, Fuller catered a George Washington’s Birthday celebration for Union generals Webster and Gillmore; he fed them on the same china he employed when he catered Confederate General P. T. Beauregard’s ball celebrating the capture of Fort Sumter four years previously. Shortly thereafter he reclaimed 77 Church Street, the original site of his restaurant, the Bachelor’s Retreat. There he hosted a banquet sometime in late April, inviting his former white clients, members of the city’s African American elite, and certain members of the provisional government to be his guests. At the time, a daily rice ration fed the 15,000 occupants of the city. Fuller, who had known the provisioners of the Union Army from the time when he supplied Charleston’s game market in the 1850s, somehow managed to secure a bounty of supplies from his old friends.

The audacity of Nat Fuller’s Feast was immediately recognized. Mrs. Frances J. Porcher, having returned from her evacuation of the city, found the event remarkable: “Nat Fuller, a Negro caterer, provided munificently for a miscegenat dinner, at which blacks and whites sat on an equality and gave toasts and sang songs for Lincoln and Freedom.” This grand dame of Charleston planter society knew exactly the significance of the feast. It heralded a new kind of civil society and promised a new ground for civility. For the first time in South Carolina an African American stood as host at a table around which blacks and whites sat subject to his hospitality and generosity.

Fuller’s Feast gestured at social reconciliation as an evolution of traditional local values—of hospitality and sociability. Its symbolic force depended on the fact that the person who initiated it did so as a natural expression of his own genius. If Fuller had not been a consummate culinary artist, if he had not demonstrated repeatedly over decades his devotion to an ideal of refined living, if he did not have so extensive a network of friends, clients, and colleagues, if he did not command a space that had a revered place in local memory, if he did not have the political savvy and business acumen necessary to secure abundant food in a time and place of scarcity, no one would have come to the feast. But Nat Fuller did have all this, and the feast took place, to the astonishment of many. Even members of the old power elite, despite their chronic myopia, recognized that a step was being taken into the future that boldly departed from the old way of doing things.

Charleston 2012: Bringing Reconciliation “to Life Again”

That was the story that I had chanced upon in 2012. The idea of possibly commemorating Nat Fuller’s Feast on the 150th anniversary of its occasion did not occur to me until a conversation in the New Orleans airport with chef Matthew Raiford as we waited for a delayed flight. An African American chef and farmer with deep Lowcountry roots, Raiford first chatted with me about our mutual interest in Gullah-Geechee food heritage. But soon the talk turned to the history of black fine dining, and the work of the great caterers in the eastern cities during the nineteenth century. I told Raiford the story of Nat Fuller. He immediately declared, “we have to do something to bring his life and example to life again!” He gave me the name of his friend, Chef Kevin Mitchell at the Culinary Institute of Charleston. Mitchell was the secretary of the Edna Lewis Foundation for African American Culinary History.

That was how the idea began, but there was still a long way to go. How do you get a community behind something? You have to get like-minded people to sign onto an idea. You have to publicly broach some possibilities. I briefly told the story of Nat Fuller and his feast in an article published in the December holiday issue of Charleston Magazine entitled “Charleston’s First Top Chefs.” Charleston had emerged in the past decade as a world tourist destination on the basis of its cuisine, its history, and its hospitality. But Charleston had a curiously vacant culinary history—it revered recipes rather than celebrated chefs. New Orleans had its Antoine and its Jean Galatoire; New York had its Lorenzo Delmonico. Boston had its Harvey D. Parker. Who did Charleston have? I argued that Nat Fuller could supply a focus for the city’s culinary past; his story could revise the history of defeat and Reconstruction and tell us something new about the ethic of hospitality. In the last sentences of the article I suggested that re-staging Nat Fuller’s Feast might be the most resonant way to commemorate the end of the Civil War in Charleston. The magazine’s editor, Darcy Shankland, was taken with the idea and urged me to develop it.

Before anything concrete could be done, we had to have a chef who could perform the artistry of Nat Fuller. In April of 2014 I approached the man whom Raiford had recommended, chef Kevin Mitchell. He and his colleague chef Mike Carmel listened to the story of Nat Fuller, and they instantly committed to the idea. They would put the resources of the Culinary Institute of Charleston behind the event.

We began our planning with several foundational premises. No institution would be given oversight of the planning or conduct of the event—no university, governmental agency, foundation, or association. We wanted to avoid the pitfalls of bureaucracy and proprietary sensibility, so we formed an ad hoc group of interested citizens affiliated with an array of bodies. We decided that the event would approximate the experience of the original as closely as possible. That meant the guests would be for the most part invitees; they would not pay for their meal, but receive it as a gift of the host. We also decided that the event would be a sociable meal, not a fundraising event, reconciliation workshop, or history lecture. Yet we wanted to raise historical consciousness of Fuller and his times; we wanted the work of reconciliation to be furthered, and we wanted the gathering to be something more than a gusto and gab fest.

A broad net was cast inviting people to the first planning session in September 2014. Those who answered the invitations and appeared at the monthly gatherings thereafter constituted the organizing committee—a diverse group of culinarians, academics, community leaders and artists. The first decision was about what to name the event, and we decided on Nat Fuller’s Feast, to reflect a sense of plenitude. The number of attendees was capped at 80. A few seats would be reserved for media and for patrons.

Reenacting without Romanticizing

Because reenactment has become a peculiarly dominant way of recalling the Civil War, we debated the extent to which we should take up that mode of memory. For diners to dress in crinolines and cutaways seemed too much a playful masquerade, and too reminiscent of those fantasies of antebellum moonlight and magnolias that have colored white nostalgia. So we quickly determined that it would be Fuller’s food that would be reenacted. Diners would appear in modern dress. But other attendees would recall the dress of the Civil War. Recalling the scene of the original feast—the military occupation of the war-battered city—suggested that we should have the African American reenactors of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment present at the event to recall the reversals of fortune experiences by Charlestonians in the spring of 1865. We determined to contact Joseph McGill and the regiment.

Next decision: who should attend the feast? The original company had been beckoned by invitation. We should do the same. But who should determine who received an invitation, and what should be the criteria for consideration? Dr. Bernard Powers, a historian of the world of African American artisans in the nineteenth-century South at the College of Charleston, agreed to chair the committee, a group that he recruited. Early on, that committee determined that Nat Fuller’s interests in reconciliation might best be served if, 150 years later, local men and women who had demonstrated an interest in promoting social dialogue, reconciliation, and community leadership would be invited, as well as community leaders, artists, and historians. We also determined that we would invite Nat Fuller’s descendants if any existed.

But there was a drawback: privately inviting attendees to the feast risked forfeiting public interest in the event. In order to share the event with a larger audience, we hit upon an ingenious way of piquing popular curiosity. With the aid of food writer Hanna Raskin of the Charleston Post & Courier, we held a contest open to anyone over 18 years old. Six seats would be reserved for members of the public who could make the most eloquent case, referencing Nat Fuller’s life and ideals, for why they should have a place at the table. This stimulated intense interest and gave rise to a number of cogent and persuasive petitions.

Nat Fuller and the Work of History

Yet newspaper contests or biographical sketches cannot replace history. One of the most time-consuming, but ultimately rewarding, labors associated with the feast was researching the story of this slave who became the “presiding genius” of Charleston cuisine while still in bondage. How did he learn so technical an art as pastry cookery? How could he possibly have secured materials for a feast in an occupied city in which the population received daily rice rations? How did he secure the liberty to run the Charleston game market or have his own three-story brick restaurant? Kevin Mitchell and I, with the aid of Jane Aldrich, began composing a biography of Fuller and an account of his food. The Lowcountry Digital History Initiative agreed to design a website using the material—it was launched two weeks before the April 19 date of the feast.

Because web venues for scholarship often do not handle details of documentation well, and web readers tend to become impatient with longer reading experiences, we decided to publish a booklet to be distributed gratis at the feast that would contain a 77-page treatment of Fuller’s life, his culinary context, and the food prepared. It also contained the menus, the sponsorship information, and the roster of people responsible for creating the event. This biography is currently on sale and the proceeds go entirely to two projects: the Nat Fuller Fellowship at the Culinary Institute of Charleston, and the Nat Fuller Curatorship for African American craft and art at the McKissick Museum, at the University of South Carolina.

When word of Nat Fuller’s Feast began circulating, interest began to grow beyond Charleston. One of the members of the original organizing committee, Dr. Jane Przybysz, director of the McKissick Museum, inquired whether we would consider having concurrent feasts staged at other places. Because the ideals that Fuller espoused were not restricted to a time and a place, we determined that we would welcome other Nat Fuller Feasts and arrange for the materials we prepared to be made available to the organizers. Feasts were set in motion in Columbia, South Carolina, and Clinton, South Carolina. Enthusiasm continued to grow and ad hoc feasts were held without our aid in New Hampshire and Jackson, Mississippi,.

Finding a Twenty-first Century Space that Could Welcome the Past

But back in Charleston, we still had to decide where the feast should be held. Did the building that housed Nat Fuller’s Bachelor’s Retreat still survive? Research by Jane Aldrich determined that it was indeed still standing—as 103 Church Street in Charleston, now the Charleston Renaissance Gallery, a fine art gallery devoted to the tradition of Southern painting, graphic arts, and folk pottery. We met with the owners, Robert and Jane Hicklin, who were delighted with the idea of hosting the event. However, a tour of the space indicated that, while it would be ideal for a reception, it would not serve for a sit-down dinner. At this juncture, Sean Brock, the James Beard Award-winning chef of McCrady’s and Husk Nashville, volunteered the use of McCrady’s Long Room, one of the great public dining rooms surviving from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in the city. Brock, a champion of southern food heritage, put his full authority and talent behind the project from the beginning.

With the location in place, our attention turned to the food. We were dedicated to ensuring that the feast in Charleston reflect the professional standards of cuisine and service that Fuller embodied. Kevin Mitchell headed the triumvirate of chefs who would direct the preparation of cuisine. Chef Banjamin “B. J.” Dennis would be in charge of the cocktail reception at the site of the old Bachelor’s Retreat. Sean Brock would handle the fish course and sauces. Kevin Mitchell would have general oversight of the banquet. Pastry chef M. Kelly Wilson would handle desserts. We hired a professional event manager, Stephanie Barna, a veteran of the Charleston food and hospitality. She proved an energetic and efficient organizer. We also felt it important to have a visual signature to the print materials associated with the feast—the invitation, the booklet, the menu, the archival video. We hired Marcus Amaker to give the feast a recognizable face.

A Problem Shared in Past and Present—How to Fund the Feast?