“Making the right of citizenship identical with color, brings a stain upon the State, unmans the heart of an already injured people, and corrupts the purity of Republican Faith.”

(1841 Petition from the “Colored Citizens of Rhode Island to the Rhode Island Constitutional Convention”)

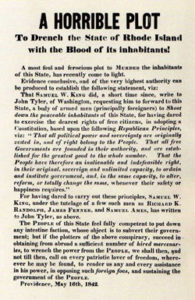

Early in the morning of May 18, 1842, Thomas Wilson Dorr, the “People’s Governor,” and a band of more than two hundred followers advanced on the state arsenal in Providence. The goal was simple: use the weapons within to seize power from Governor Samuel Ward King and forcibly establish the People’s Constitution. Having tried diplomacy and appeals to President John Tyler, the elite revolutionary Dorr turned to more drastic measures to achieve recognition as the legitimate governor of his native state. Rhode Island was now in a standoff between two men who each claimed to have been legally elected governor.

The 1842 standoff resulted from years of repeated attempts to revise the existing instrument of government, a charter granted by King Charles II in 1663. The charter had become outdated, and its restrictive suffrage requirements left many Rhode Islanders disenfranchised. After repeated attempts to redress the issue within the state legislature failed, reformers took matters into their own hands. For Dorr and his followers, the Declaration of Independence was “not merely designed to set forth a rhetorical enumeration of an abstract barrier to belligerent rights.” In late 1841, their Rhode Island Suffrage party sponsored its own popular convention to draft a new constitution. Delegates to the “People’s Convention” believed that they were acting on their constitutional right to alter or abolish an archaic government that no longer embodied the interests of the majority. The resulting constitution was subsequently promulgated and ratified in town meetings across the state. A government was then elected by universal, white, male suffrage under the new constitution. However, the Charter government was not about to go away quietly. On April 2, 1842, authorities issued an “Act in Relation to Offenses against the Sovereign Power of the State.” This act, which was derisively referred to by the suffrage supporters as the Algerine law, after the tyrannical Dey of Algiers, penalized anyone participating in elections under the People’s Constitution and declared that all who assumed office under the document were guilty of treason against the state.

Political observers recognized that the implications of the conflict extended well beyond Rhode Island’s idiosyncratic political history. James Simmons, Rhode Island’s Whig senator, remarked that if Dorr’s insistence on the right of the people to alter and abolish the government whenever they deemed necessary won out, it would place a powder “magazine beneath the fabric of civil society.” After the rebellion had been put down, the archconservative Francis Wayland, who was also serving as the president of Brown University, maintained that Dorr nearly plunged the nation “into the horrors of civil war.” In contrast, the aging Andrew Jackson maintained that the Dorrite movement was constitutionally legitimate, and represented the rightful exercise of the people’s power.

A lawyer by training, the 36-year-old Dorr (fig. 1), who idealized Jackson, was not cut out to lead a rebellion of the disenfranchised. Unskilled in military matters, Dorr’s attempt to fire on the arsenal with a 70-year-old cannon backfired in more ways than one. The cannons coughed up water, not lead balls. Even worse: many of his supporters deserted after the fiasco either because they feared arrest or because they disagreed with Dorr’s move from a war of words to armed conflict. One month later, Dorr and what was left of his followers reconvened at the village of Chepachet in northern Rhode Island. The primary purpose was to reconvene the People’s Legislature. However, when slightly more than 200 local supporters came to his aid and the hundreds he expected to arrive from New York City failed to make the journey, the disillusioned and disgraced People’s Governor fled the state.

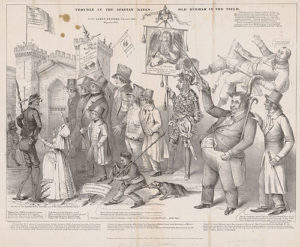

Back in Rhode Island, forces loyal to Governor King, including some 200 black men from Providence, summarily arrested hundreds of suspected Dorrites. The Law and Order forces, a coalition of Whigs and conservative Democrats, needed all the troops they could get their hands on because many of the state militia units were loyal to Dorr. Black participation in squashing the rebellion made a deep impression on William Brown, the grandson of slaves who had once been owned by the famous merchant turned abolitionist Moses Brown. At numerous points in his memoir, William Brown pointed out that many blacks “turned out in defense” of the newly formed Law and Order party. The “colored people,” according to Brown, “organized two companies to assist in carrying out Law and Order in the State.” One Dorrite broadside viciously depicted blacks at a table with dogs eating and drinking like barbarians at the conclusion of the rebellion. Indeed, the Law and Order party was frequently referred to as the “nigger party” by the Dorrites (fig. 2).

Ironically, the disenfranchised black allies of the Law and Order party helped to put down a rebellion that claimed to speak on behalf of the disenfranchised. Indeed, the black men who made such an impression on Brown played a key role in suppressing a rebellion that they once had every intention of joining because of its egalitarian ethos. Just as ironically, blacks’ support for the Charter government, a relic of Rhode Island’s colonial past, helped secure their voting rights when the state approved a new constitution in 1843. The former slave and staunch abolitionist Frederick Douglass maintained in his autobiography that the efforts of black and white abolitionists “during the Dorr excitement did more to abolitionize the state than any previous or subsequent work.” One effect of the “labors,” according to Douglass, “was to induce the old law and order party, when it set about making its new constitution, to avoid the narrow folly of the Dorrites, and make a constitution which should not abridge any man’s rights on account of race or color.” This legal triumph, the only instance in antebellum history where blacks regained the franchise after having it revoked, was rooted both in the particular political and economic situations of Providence’s black community and in the Revolutionary rhetoric that was part and parcel of Dorr’s attempt at extralegal reform.

Rhode Island’s black population was small, less than three percent of a total population that numbered 108,837 in 1840. Blacks resided throughout the state, but the majority were concentrated in Providence; in 1842, the year of the rebellion, the Providence Directory listed 287 blacks as head of households. By 1830, roughly one-half of Providence’s black population owned their own homes while the other half lived in tenements; the majority were situated in Olney’s Lane, Snow Town, and the evocatively named Hard Scrabble—all black enclaves in the seedy areas of the town. Most of the occupations listed for the “colored population” were for menial types of employment. Because they were denied higher paying manufacturing jobs in Providence, many blacks were forced to make ends meet by opening restaurants and taverns catering to the large sailor population that streamed into the port of Providence or working as domestic servants. William Brown’s memoir testifies to the various forms of discrimination that confronted Providence’s black population. “The feeling against the colored people was very bitter,” Brown wrote. Mobs were “the order of the day, and the poor colored people were the sufferers.” At theaters and lecture halls in Rhode Island, as in those across the North, blacks could only enter if they agreed to sit in the balcony. Black children were often prohibited from attending public schools with white children; above the elementary level, few schools admitted blacks. The black minister Hosea Easton proclaimed in a Thanksgiving Day address in Providence in 1828 that black youth were “discouraged, disheartened, and grow up in ignorance” because of the racism they faced. Racism led to more than discouraged youth. In 1824 and again in 1831, Providence experienced major race riots.

Despite these difficulties, many members of the black community prospered and acquired sufficient wealth to meet the freehold requirement before they were legally disenfranchised in 1822. Arguing that they were already citizens because of past military service during the American Revolution, blacks quickly pushed back against the state’s white ruling elite. Black leaders understood that they needed to encourage their community to demonstrate self-reliance, virtue, and the capacity for improvement if they were to regain their voting privileges. Nathaniel Paul, pastor of the New African Union Church in Providence, told his congregation in 1822 to work hard to “convince” the white world that although their “complexion might differ,” they had “hearts susceptible of feelings, judgment capable of discerning, and prudence sufficient to maintain” their “affairs with discretion.” Whatever status an immigrant managed to attain, his son would automatically be a native-born white man, unconditionally entitled to full legal rights and privileges. Black leaders, on the other hand, had to demonstrate the worthiness of an entire group anew with every generation. After years of working to create an image of respectability, Providence’s African American community hoped that the Rhode Island Suffrage Association, which was formed in March 1840, would take up their call for equal rights and helped them regain the franchise. Their hopes were quickly dashed.

If Providence’s blacks were frustrated by the limited rights granted them by the state government, the Suffrage Association was angered by the government itself. Ironically, the first American colony to declare its independence from British rule and industrialize was the last to relinquish a system of government based on a royal charter. As Dorr and his followers pointed out, the colonial charter, while progressive by seventeenth-century standards, posed any number of problems for a nineteenth-century American state. Some of the most pressing problems centered on the franchise, which restricted suffrage to men owning $134 in land or paying $7 in rent. But the market revolution of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries accelerated urban growth and contributed to the formation of a large landless class in and around the capital city of Providence. By 1840, Rhode Island had the highest proportion of manufacturing workers in the nation and was one of just two states in which more workers labored in manufacturing than they did in farming. However generous the charter may have seemed in the seventeenth century, by the 1840s, roughly 40 percent of the state’s white men, many of them Irish Catholic immigrants, were disenfranchised. Small wonder, then, that the attempt to reform the state constitution and expand the franchise attracted a large and enthusiastic following among white males. And small wonder that the extralegal attempt to draft a new constitution in 1841 received the support of a clear majority of Rhode Islanders. When the ballots were certified on January 13, 1842, the people of Rhode Island found themselves with two constitutions. A few months later, two men would run for governor under different constitutions.

As Rhode Island’s constitutional crisis unfolded, Providence’s African American community proved to be nimble political operators, despite the efforts of the Dorrites and the Charter authorities to use them as political fodder. Blacks managed to gain a measure of political power by supporting the Charter authorities, while at the same time helping to defend themselves against hostility from white suffrage reformers, who for the most part saw blacks and their abolitionist allies as a political liability and thus refused to remove the “white only” clause in the People’s Constitution. The conservative political satirist William Goddard, writing as “Town Born” in the pages of the Providence Journal, pointed out the Dorrites’ moral failings. Putting words into the mouths of a Dorrite speaking to blacks, “Town Born” wrote: “You may ride along in the same train of revolution with us if you please, but alas! It must be in the James Crow car.” “Town Born” asked the Dorrites that if “all men are born free and equal,” and if “the right to vote be a natural and inalienable right, why does the mere accident of color make a difference?” In reality, however, the Law and Order party saw blacks as a political and physical weapon that could be wielded against the Dorrites. As one female Dorrite said at the time, the Law and Order forces “made the colored men voters, not because it was their right, but because they needed their help.”

The Rhode Island Suffrage Association began gearing up for the 1841 constitutional convention months in advance. To mobilize supporters, the association advertised the convention in the press, stressing the need for universal turnout. “Let every man who is in favor of a Republican form of government go to the polls on the last Saturday in August, and vote for men good and true, to assemble in Convention,” proclaimed on announcement. The day before the vote, they exhorted citizens to go “TO THE POLLS TOMORROW: Let every American citizen in the State devote the day to his country.” Despite the inclusive language, the references to “every” American and “every” citizen, black voters were turned away on election day.

The Association’s refusal to recognize black voters in August turned out to be a portent of things to come. The deciding moment for black suffrage at the People’s Convention occurred on October 8, 1841. Just before the opening of the evening session, Dorr was presented with a memorial, a petition from members of the Providence black community, protesting the commitment of many of the delegates to universal white male suffrage.

At the start of the session, Dorr told the assembly that he had received the petition and asked that it be read by one of the secretaries of the convention. This request was challenged on the suspicion that the petition might have been written by a white person eager to discredit the suffrage cause. Dorr reassured his audience that the messenger who handed him the petition said that it was written by Alexander Crummell, the young black minister of Christ Church in Providence. Before coming to Providence, Crummell had fought an unsuccessful battle against New York Democrats in an attempt to abolish the $250 freehold for voting, which affected both whites and blacks. His tenure as pastor of Christ Church was riddled by controversy—he often disagreed with the parish officers. But as an educated minister Crummell often served as the de facto scribe and spokesman for the city’s black community. The memorial he drafted on the community’s behalf maintained that Rhode Island’s African American community was “unwilling” to let “this sore, grievous, and unwarrantable infliction” to be “made upon” their “already bruised hearts.” A white-only clause was regarded “as unwarrantable, anti-republican, and in tendency destructive; and, as such, we protest against it.”

The petition went on to explain that Providence’s blacks were mostly native born citizens; as a community, they had worked their way up to respectability and economic competence. As “citizens,” proclaimed the petition, they claimed an “equal participation in the rights and privileges of citizenship.” This was no different from the views of Aaron White Jr., one of Dorr’s close political allies, and a proponent of black suffrage. White would later argue that as “citizens of the Union” the “rights” of a majority of Rhode Islanders had been “in repeated instances most outrageously violated by the men in power beyond all question.” White hoped that “some way might be found that would at least restore” the rights “under the national Constitution.” Crummell’s petition went on to argue that as “native born citizens and not accustomed to a political creed repugnant to democratic principles and republican usage,” the signers were “members of the state of Rhode Island under the government of the United States.” The “repugnant” political creed was a reference to Catholicism, invoking common fear about the consequences of enfranchising the growing ranks of Irish immigrant laborers. The gist of the argument coming from the African American community, however, was that excluding them from the elective franchise was anti-republican, that it violated the cornerstone of Dorrite ideology. The petition was signed by Ichabod Northup, Samuel Rodman, James Hazard, George Smith and Ransom Parker, all leading members of the black community.

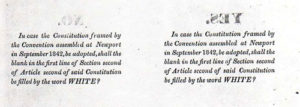

For a moment it seemed that the petition would be well received: Dorr himself openly favored it. He was afraid that the Suffrage party’s commitment to popular sovereignty would appear hollow if blacks were excluded from the franchise. Duttee J. Pearce, however, disagreed. Pearce, whom Dorr would later come to despise, argued that the People’s Constitution would never be ratified if it included a provision for black suffrage. Following the reading of the petition and after much discussion on the convention floor, the word “white” was retained by a vote of 46 to 18. Primarily to appease Dorr, a clause was inserted to submit the question of black suffrage to the people after the constitution had been adopted.

The race-based franchise endorsed by the People’s Constitution was a bitter disappointment to Rhode Island’s African American community and their abolitionist allies. Never mind that the Charter government, holding its own concurrent constitutional convention, had likewise excluded black participation. The Dorrites, who had dashed blacks’ expectations, attracted the greatest sanctions from anti-slavery activists—and in October of 1841 there was no shortage of abolitionists in Providence. Anti-slavery activists, sensitive to Rhode Island’s significance in the struggle for black civil rights, had scheduled their own convention to coincide with and influence the two competing constitutional conventions. A who’s who of New England abolitionism descended on Providence. William Lloyd Garrison, John A. Collins, Stephen S. Foster, Abby Kelley and Frederick Douglass were all in attendance. Kelley braved snowballs, rotten apples and eggs, jeers, and threats so “murderous” that she was long plagued by “troubled dreams.” This was nothing new for Kelley. In May 1838 she braved flying stones and brickbats in order to give an address at Pennsylvania Hall. Garrison had a sizeable number of admirers in Rhode Island through his marriage to Helen Benson, the daughter of one of the founding members of the state’s anti-slavery society.

The Dorrites and the abolitionists confronted each other in the middle of the anti-slavery convention’s deliberations, when Joseph Brown, president of the Rhode Island Suffrage Association, was allowed to address the assembly. Brown argued that the Suffrage Association was charged with advocating for the greatest good of the majority of citizens in the state, which was clearly composed of the white working class. Once universal suffrage was achieved for whites, Brown assured them, black suffrage would soon follow.

Garrison responded to Brown’s remarks in what one newspaper referred to as a “strain of epithets.” According to Garrison, the suffrage reformers “were engaged in a mean and contemptible business—the dastardly act of the Suffrage men show them to be possessed of mean and contemptible souls.” The anti-slavery convention concluded the following day with a number of resolutions, one of which was that no man who professes to be an abolitionist could consistently vote for a constitution with the word “white” in it.

The enmity between the two reform movements increased through the winter. Abolitionists cancelled their subscriptions to the New Age, the suffrage organ, attempting to bankrupt it. The state anti-slavery society also began publication of The Suffrage Examiner, a newspaper whose sole purpose was the defeat of the People’s Constitution. The tactics of the anti-slavery movement, ranging from barnstorming to press wars, proved ineffectual. In some instances, abolitionists were denied halls in which to hold their meetings; in other instances, speakers were harassed. Mobs of Dorrites broke up abolitionist meetings, made proslavery speeches, and derided the Charter government supporters as the “nigger party.” Although the mainstream press provided detailed accounts of these altercations, the suffrage papers paid hardly any notice.

As tension escalated, Dorrites who favored black suffrage could only ask for patience and promise action in the future. In a communication addressed “To the Abolitionists of Rhode Island,” Benjamin Arnold Jr., Samuel H. Wales and William Wentworth, who had voted in favor of black suffrage at the People’s constitutional convention, tried to reassure readers that the issue was not dead. They pointed out that the People’s Constitution mandated a referendum on black suffrage. The authors acknowledged the racism of many of the suffrage reformers, but pleaded with the abolitionists not to let this prevent them from supporting the People’s Constitution. The sentiments expressed by a friend of Dorr’s in Fall River, Massachusetts, are representative of many Suffrage party members. Expressing his disappointment that the People’s Constitution did not contain a provision for black suffrage, but also recognizing that the Charter government’s constitution was “still less liberal than the People’s in every other particular and absolutely and irretrievably shut the door against ever admitting the colored man to vote,” Louis Lapham maintained that he was “convinced” that the Suffrage party “had probably put that question in the most liberal shape that circumstances would at the time render successful.” According to Arnold, Wales, and Wentworth, the suffrage reformers were “bound to carry out” their “principles to every practicable, but not to every impracticable extent, because principle” would not permit them “to sacrifice a benevolent attainable object to a mere nominal and useless theoretical consistency.” In closing, the three authors reminded the abolitionists of the simple fact that the draft of the Charter government’s constitution contained neither provisions for black suffrage nor a clause for the future addition of it.

Following the ratification of the People’s Constitution, Dorr rallied his supporters to vote down the Charter constitution, with the precariously narrow margin of 8,689 to 8,013. The Charter government had gained ground among working class whites by removing the real estate requirement for native-born white men’s suffrage and by making effective use of nativist fear tactics. The Catholic bishop of Boston actually warned his flock in Providence to stay out of the Rhode Island dispute so as to avoid trouble. Support for Dorr and the People’s Constitution was eroding. As for Rhode Island’s African American community, despite its petitions and assistance from nationally renowned abolitionists, it was no better off than it had been before agitation for suffrage reform commenced.

During the early months of 1842, Dorr and his followers busied themselves setting up a new government under the People’s Constitution. Elections were held in April. Dorr and the other slate of candidates ran unopposed. With a throng of supporters winding their way through the streets of Providence, Dorr was inaugurated governor on May 3. That month it became evident that Rhode Island was on a collision course between the existing Charter government under Samuel Ward King and the People’s Government under Thomas Wilson Dorr. Even with all the disappointment created by the white-only clause in the People’s Constitution, blacks were slow to desert the People’s Government and were ready to take up arms to aid their cause. As late as May 17, the night before Dorr attempted to attack the arsenal (fig. 3), the members of Providence’s Christ’s Church seemed to favor supporting Dorr. The church’s record book noted that at the closing of the vestry meeting on the night of attempted attack, parishioners paid homage to the “People’s Governor.” But the fire bombing of their congregation on the evening of March 24 certainly made their decision to aid the Charter authorities easier. As historian Mark Schantz has noted, while it was unclear exactly who set fire to the church, “such an act fits the broader pattern of racial antagonism demonstrated by the suffrage reformers during the previous year.”

By June, when the Charter government called out its militia companies to put down the insurrection (fig. 4), Providence’s blacks were willing to cast their lot with the established government, the same government that had denied them the franchise for the past twenty years. More than 200 black men joined the nearly 3,500 men who comprised militia and volunteer companies. Like white volunteers, blacks policed city streets, manned fire companies, deployed throughout the state, and guarded Dorrite prisoners. William Brown recalled that blacks were integrated into the militia companies of the City Guard. A reporter for the Boston newspaper Emancipator and Free American noted that blacks in Rhode Island were “placed in the ranks according to their height and I saw no manifestation of disrespect toward either one of them, by any member of the company, but on the contrary all praised and honored them for their noble devotion to the interest of the great cause of regulated civil liberty which they were now called to defend.”

Such ready acceptance of black volunteers demonstrates the desperation of the Charter government. According to William Brown, Dorr supporters argued that “if it were not for the colored people, they would have whipped the Algerines, for their fortifications were so strong that they never could have been taken. Their guns commanded every road for a distance of five miles. Why then did you surrender your fort, I asked, if you had eleven hundred men to defend it? They said ‘Who do you suppose was going to stay there when the Algerines were coming up with four hundred bull niggers?'”

Regardless of the government’s motivation for incorporating black volunteers into its defense, Providence’s white community began to take notice. Just one day after the Charter government deployed its forces to Chepachet, the Journal noted approvingly:

THE COLORED POPULATION of our city, have come forward in the most honorable manner, and taken upon themselves the charge of the fire engines. They have pledged themselves to assist in the protection of property from fire and plunder, while the other inhabitants are engaged in the defense of the State.

The week following Dorr’s defeat at Chepachet, the city’s black community was represented in the July 4th parade by its own marching band, complete with musical instruments supplied by the state from items confiscated at Chepachet.

As tensions caused by the rebellion diminished in the early fall of 1842, the Charter government convened yet another constitutional convention and asked Rhode Islanders to vote on yet another constitution. Although it eased suffrage requirements, the reform constitution was a far cry from Dorr’s vision. It mandated a one-year residency requirement for freeholders, a two-year residency requirement for the native born without real estate but owning $134 worth of personal property. Naturalized citizens were still required to own $134 worth of real estate. The rural Democrat Elisha Potter noted in a letter to former governor John Brown Francis that the Law and Order party “would rather have the Negroes vote than the damn Irish.”

When the constitution was put before the state, all citizens who were to be admitted to the franchise under the new suffrage requirements were allowed to vote. The constitution was approved by a lopsided margin of 7,024 to 51 and the provision for black suffrage passed with 4,031 votes in favor to 1,798 against, a two to one margin (fig. 5). Even Dorr, the ardent antislavery Whig politician in the 1830s and friend of black suffrage in 1841-42, complained later that “naturalized citizens are not allowed to vote … while the blacks are on the [same] basis of the native whites.”

In the spring of 1843, with Dorr living in exile in New Hampshire and then Massachusetts, the Rhode Island Suffrage party decided that their best course of action was no longer revolutionary reform, but rather registration under the new constitution. Their goal was to retake the reigns of government through the ballot box. Their hopes were quickly dashed, however, as the Law and Order party easily won the election. On April 13, 1843, one of Dorr’s political correspondents wrote to the erstwhile reformer, blaming the resounding political defeat on Rhode Island’s black population. “The colored people, had they voted with us,” said Samuel Ashley “would have given us” the “majority.” Ashley maintained that blacks living in Providence “were cajoled, treated, collected together in the arsenal” and “made to believe as some have themselves since told me, that if they voted with” the Dorrites, “the People’s constitution, which rejected them as voters” would have been adopted. Dorr’s close friend Catherine R. Williams said that blacks “were marched like slaves to the townhouses to vote” in Providence and in Bristol.

In a society resting, rhetorically at least, on the ideal of equality, the boundaries of Rhode Island’s political community took on extreme significance in 1842 and 1843. The Dorrites, abolitionists, and black leaders all understood the “privileges and immunities” clause of the Constitution to provide a broad protection for a range of rights, including suffrage. However, as historian David Roediger has argued, blacks “were seen as anti-citizens” by the Dorrites. They were viewed “as enemies rather than the members of a social compact.”

In the pages of The Wampanoag and Operatives’ Journal, the famous journalist and novelist Frances Whipple Green maintained that in “excluding their colored fellow citizens from the rights and privileges, which they were seeking for themselves,” the Dorrites “forfeited the esteem and confidence of all the true and consistent friends of freedom.” According to Green, “the word ‘WHITE'” in the People’s Constitution was “a black mark against” the suffrage reformers. Yet while her abolitionist sympathies initially provoked her to express outrage at the “odious ‘WHITE’ Constitution,” Green eventually supported the suffrage cause and the People’s Constitution. Even though she was well respected in the black community for penning the 1838 memoirs of the part-Narragansett Indian, part-black whitewasher Elleanor Elbridge, Green was able to put aside her feelings of outrage at the exclusion of black voters in the People’s Constitution in order to work for suffrage reform for white workers. Like most of the Dorrites, Green quickly backpedaled on her egalitarian principles.

In her pro-Dorrite tract, Might and Right, penned two years after Dorr’s rebellion had been put down, Green lamented the fact that the abolitionists, “the professed philanthropists of the North,” failed “to enter their protest” against the treatment of the Dorrite prisoners. In her description of the inhumane treatment of prisoners held in the Rhode Island capital city of Providence, the coastal town of Bristol, and the city of Newport in the summer of 1842, Green remarked that if “a band of colored men had been marched through the streets … under the same circumstances all New England would have been in a blaze. I have yet to learn, that black men are better than white men, or that their rights are any more sacred.” Green’s allusion to “colored men” being “marched through the streets” referred to the surrender of suspected fugitive slaves to southern slaveholders, a prospect that was the focus of widespread anxiety and fear through the North. Green’s lament in Might and Right about the lack of abolitionist support for the Dorrites’ version of suffrage reform was somewhat disingenuous. She knew perfectly well why abolitionists failed to come to the aid of the Dorrites. Green herself had supplied the answer two years before. But looking back on the rebellion’s failure, Green took aim at abolitionists, arguing that their single-minded opposition to disenfranchisement based on skin color prevented them from seeing other, deeply felt inequalities in the state’s voting laws.

Abolitionists like Abby Kelley and Frederick Douglass refused to see things this way. Douglass maintained in his memoirs that blacks in Rhode Island “cared nothing for the Dorr party on the one hand, nor the ‘law and order party’ on the other.” What Douglass wanted for the black community in Rhode Island “was a constitution free from the narrow, selfish, and senseless limitation of the word white.” In the end, Douglass and Rhode Island’s blacks prevailed.

The cruel irony of a movement that predicated itself on adherence to the Declaration of Independence only to abandon it for political expediency was not lost on the black community. The Dorrites sang praises to equality and democracy while denouncing those who cautioned the people to respect property rights and order. Yet most advocates for suffrage reform chose not to broaden their definition of democratic equality to include blacks. The Dorrites insisted that small groups within the polity, especially the abolitionists, could not be allowed to impose their particular moral vision upon the whole. Blacks ignored the pleas from the Dorrite supporters to defer their claims on the franchise until after the ratification of the People’s Constitution. Instead, leaders such as Alexander Crummell worked hard to negotiate favorable ties with white aristocrats in order to ensure that Rhode Island’s African Americans received the rights due to them as citizens. They understood that equating the rights of citizenship with skin color brings “a stain upon the state.”

Further Reading:

The best account of the rebellion remains one by Patrick T. Conley, Democracy in Decline: Rhode Island Constitutional Development, 1776-1841 (Providence, 1977), pp. 290-379. Robert Cottrol’s study of Providence’s black community is invaluable. See The Afro-Yankees: Providence’s Black Community in the Antebellum Era (Santa Barbara, Calif, 1982). See also Christopher Malone, Between Freedom and Bondage: Race, Party and Voting Rights in the Antebellum North (New York, 2008). Mark Schantz’s chapter on the Dorr Rebellion in Piety in Providence: Class Dimensions of Religious Experience in Antebellum Rhode Island (Ithica, N.Y., 2000) is first rate. Ronald Formisano and Christian Fritz present engaging and thoroughly researched chapters on the Dorr Rebellion in their most recent works. See Formisano, For the People: American Populist Movements from the Revolution through the 1850s (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2007) and Fritz, American Sovereigns: The People and America’s Constitutional Tradition Before the Civil War (Cambridge, 2008). Readers interested in race and antebellum politics should consult David Roediger’s The Wages of Whiteness (London, 2007) and Joanne Pope Melish’s introduction to the recent edition of The Life of William J. Brown of Providence, RI with Personal Recollections of Incidents in Rhode Island (Concord, N.H. 2006).

This article originally appeared in issue 10.2 (January, 2010).

Erik J. Chaput is a Ph.D. candidate in early American history at Syracuse University. He has forthcoming articles on the Dorr Rebellion in Rhode Island History and the Historical Journal of Massachusetts. Russell J. DeSimone, an independent scholar, is the compiler of The Broadsides of the Dorr Rebellion (1992) and the author of Rhode Island’s Rebellion (2009).