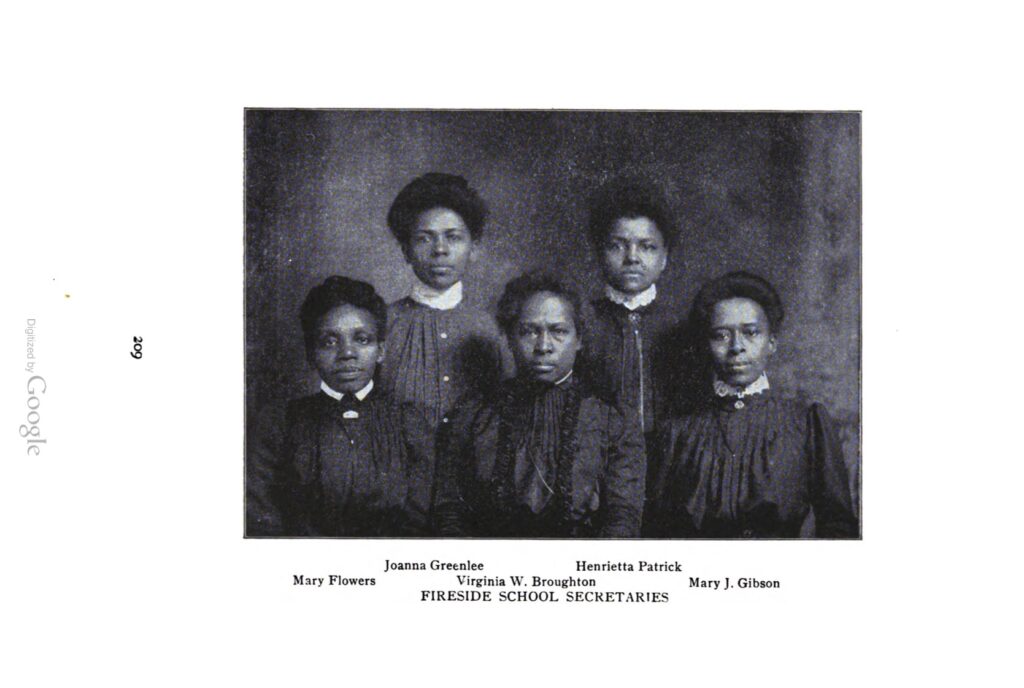

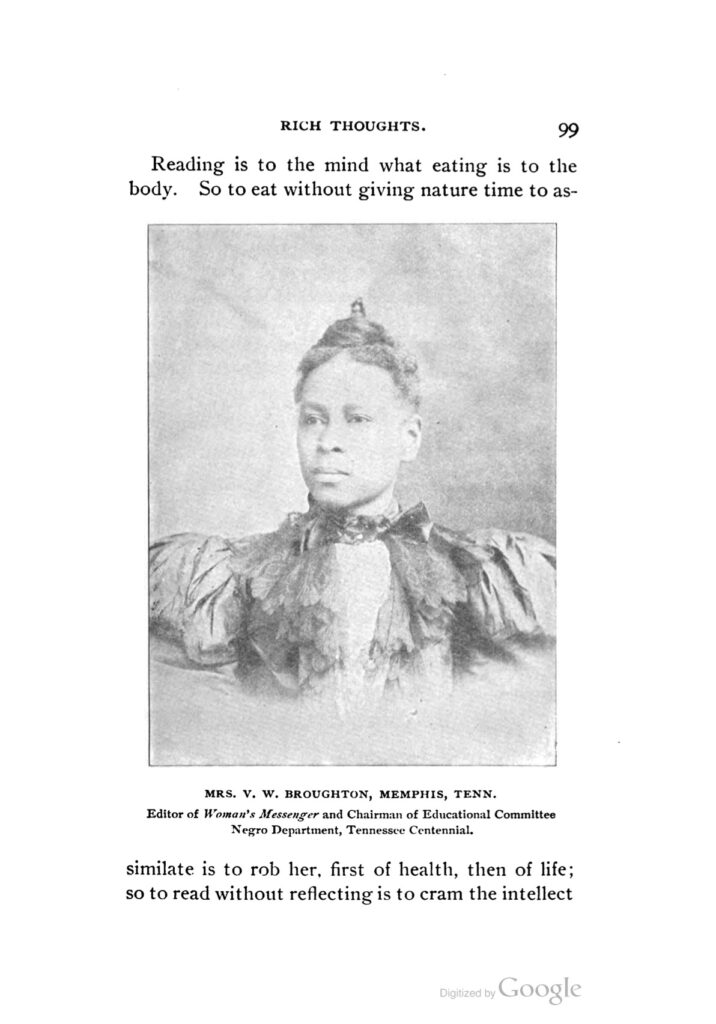

Virginia Broughton, a Black intellectual Holiness Baptist, presented and exemplified an empowered and independent Black Christian womanhood while forming sisterhood with white women beyond the accommodation versus protest dichotomy. This contributed to the maturation of self-awareness among Black women and men and provided guidance for their advancement. This foundational work paved the way for the subsequent Black intellectual and cultural revival movements and the establishment of civil rights legislation, such as Title IV and VI, which ban sex discrimination in education. Despite these advancements, the intersectional discrimination experienced by Black women in church and educational settings persists. Though the symphony of Broughton’s legacy continues to resonate, her example surely invites us to compose and play the final harmonious chord of gender equality through our collective efforts.

Further Reading:

Braude, Ann. “Women’s History Is American Religious History.” Retelling U.S. Religious History, 1st ed., Oakland: University of California Press, 2023, pp. 87–107.

Broughton, Virginia W., and Carter Tomeiko Ashford. Virginia Broughton: The Life and Writings of a National Baptist Missionary. 1st ed. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2010.

———. Twenty Years’ Experience of a Missionary. Chicago: The Pony Press, 1907.

Butler, Anthea D. “Unrespectable Saints: Women of the Church of God in Christ.” In The Religious History of American Women: Reimagining the Past, edited by Catherine A. Brekus, 161–83. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007. https://doi.org/10.5149/9780807867990_brekus.9.

Butler, Anthea D., et al. Women in the Church of God in Christ Making a Sanctified World. University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Douglass-Chin, Richard. Preacher Woman Sings the Blues: The Autobiographies of Nineteenth-Century African American Evangelists. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2001.

Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks. Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Johnson, Sarah. “Gender,” in The Blackwell Companion to Religion in America. Newark, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2010. Accessed May 6, 2024. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Lovett, Bobby L. The African-American History of Nashville, Tennessee, 1780–1930: Elites and Dilemmas. 1st ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

Moore, Christopher. Apostle of the Lost Cause: J. William Jones, Baptists, and the Development of Confederate Memory. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2019.

Moore, Joanna P. “In Christ’s Stead.” Autobiographical Sketches. Women’s Baptist Home Mission Society, 1902.

Popkin, Jeremy D.. Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian Insurrection. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/bayloru/detail.action?docID=485983.

Smith, Jessie Carney. “Virginia E. Walker Broughton (c. 1856–1934): Feminist, Missionary, Educator, Lecturer, Writer.” In Notable Black American Women, Book II, edited by Jessie Carney Smith, 57–60. Detroit: Gale Research, 1996.

Weaver, C. Douglas. Baptists and the Holy Spirit: The Contested History with Holiness-Pentecostal-Charismatic Movements. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2019.

Welter, Barbara. “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860.” American Quarterly 18, no. 2 (1966): 151–174, https://doi.org/10.2307/2711179.

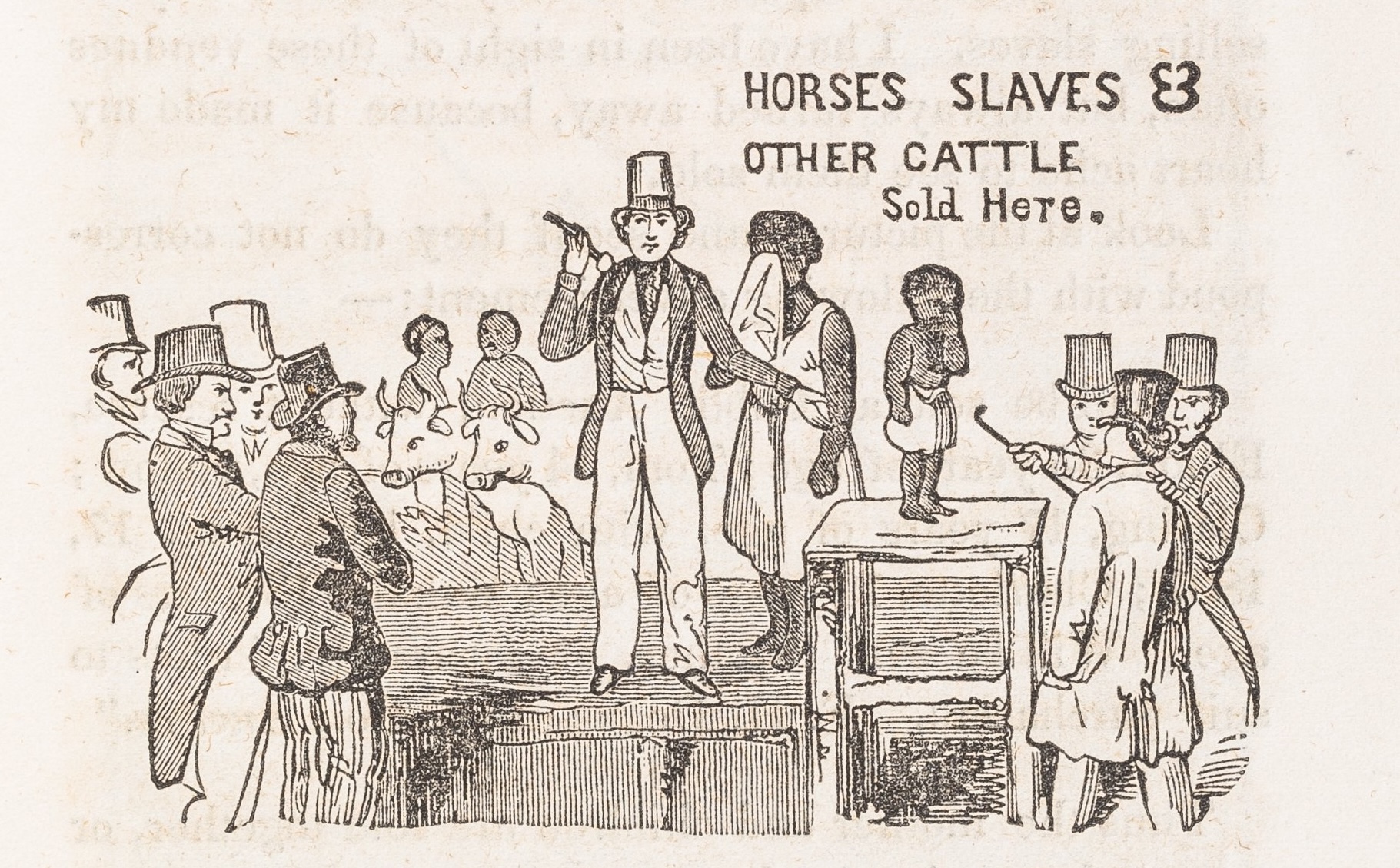

White, Deborah. Ar’n’t I a Woman? Female Slaves in the Plantation South. New York: Norton, 1985.

This article originally appeared in March 2025.

Ranmi Bae is a PhD student in religion at Baylor University. Her area of focus is the History of Christianity, in particular, the study of women, Spirit-led movements, and the interaction of Korean and American religious experience.