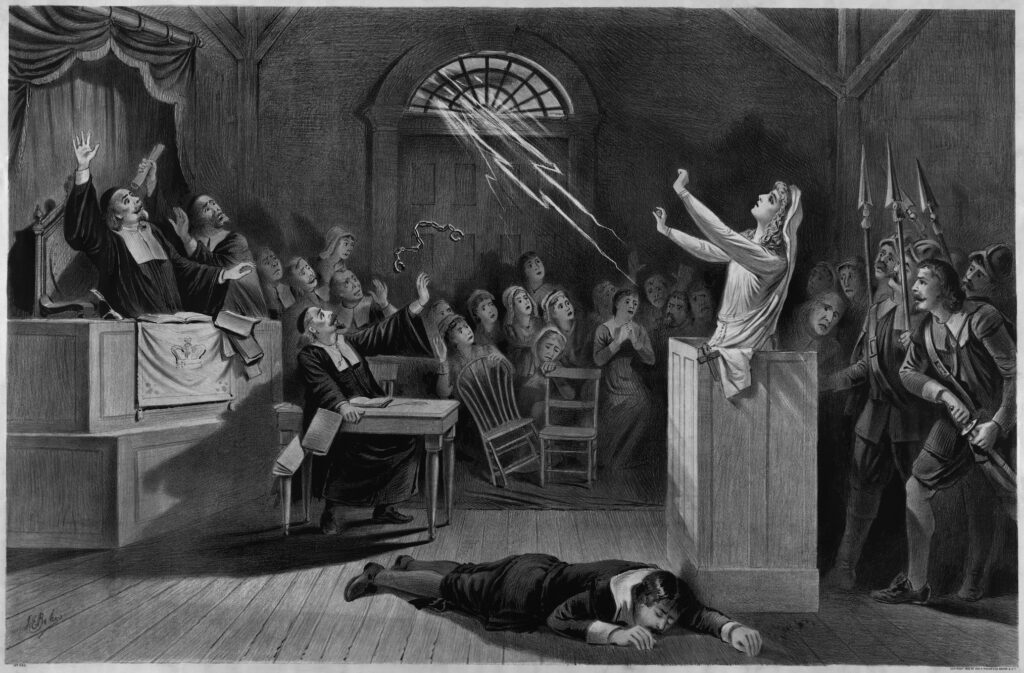

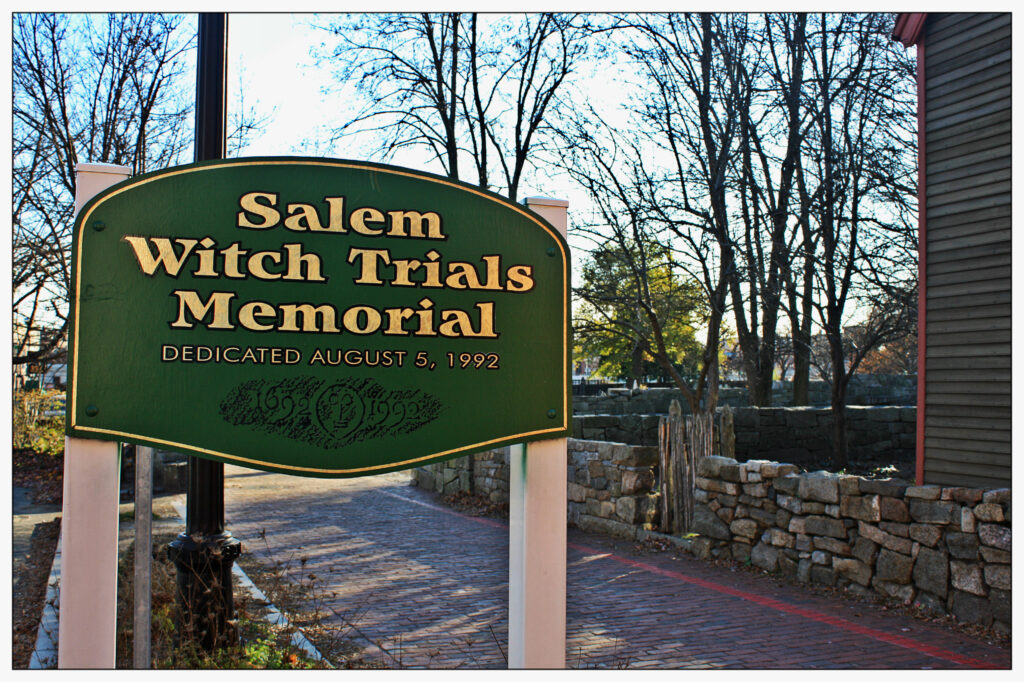

Salem, Massachusetts, has a witch problem, again. In 1692, the problem revolved around their alleged presence, with the colonizers of the Salem region fearful that malefic magic was aimed at their community. Today the difficulty arises from an attempt to monetize that history: in response to long-standing efforts to identify the city of Salem with witchery, Halloween tourism has overwhelmed the city’s historic links to witchcraft fear. In the process, they’ve all but eliminated the witches themselves. From witches’ presence as a cause of fear, we have arrived at a moment when witches are all but absent from efforts ostensibly intended to commemorate their experiences.

Salem’s Absent Witches

Such modest allusions to the colonial past were in the decided minority, however, swamped by the more generic Halloween ambience of the event.

Some of the tourists in Salem in the autumn are there for the witches, and they are bound for disappointment. From what I observed on a late September day, those with the greatest focus on witches themselves come at it from a vaguely feminist perspective. They understand witches as having been killed for being women who were powerful or at least different, and they come with a militant empathy for their plight in 1692. Arriving in the midst of Salem’s autumn extravaganza, they feel a disappointment similar, no doubt, to that of my students who come to a witchcraft class seeking a purely feminist interpretation. Our attention to larger political and social issues over the course of the term dismays those students, just as it does the (partially overlapping) group who come expecting evidence that in Salem actual witchcraft had been practiced. Watching the excesses of Salem’s “Haunted Happenings”, I share some of their feelings of disorientation and disappointment.

In Salem itself, the city’s association with witchcraft stretches the truth somewhat, since most of what happened in 1692-93 did not occur in the modern metropolis of Salem. Fear of witches first arose in what is now Danvers, then the rural hinterland known as Salem Village, a community beyond the boundaries of today’s city of Salem. The crisis reverberated out from the village to involve individuals in numerous other locations, including Salem town, neighboring Ipswich, more distant Andover, and eventually the colonial capital of Boston. Referred to as the “Salem witchcraft crisis,” this act of naming linked these events with that place. This happened even as the boundaries of Salem shrank, beginning when the village was finally allowed to become the independent town of Danvers. Although today’s Salem was as important for providing judges for the court that tried witches as it was for housing people who either leveled or were targeted by accusations of witchcraft, the popular image of witchcraft in colonial New England is irrevocably tied to the city of Salem. Popular fiction, when referencing early American witchcraft, invariably uses Salem as a shorthand term to encompass that history: Harry Potter’s international gathering of witches for a quidditch match, for instance, includes a delegation of American witches known through their residence in Salem. Many other fictional accounts similarly use Salem to stand in for witches.

Happy to exploit that connection, the Salem Chamber of Commerce has long tried to promote tourism from the platform witchcraft offers. Some components of the tourism extravaganza that overwhelms Salem these days have been around for decades. When a graduate student working in the archives there in the 1980s, I was bemused by advertisements for the Witch Dungeon tourist attraction. I knew that colonial Salem hosted no massive, ancient edifices capable of containing the stereotypical medieval dungeon. The dungeon concept, like much of popular witch lore in the United States, equates colonial prosecutions of witches in the late 17th century with (mostly earlier) European scares. The dungeon represents just one example of this tendency to understand New England and Protestant Salem in European and Roman Catholic terms.

Salem now offers stores and tourist attractions throughout the year that make the witchcraft link, but it is in the seven weeks surrounding Halloween that the city doubles down on its status as “Witch City.” Beginning in mid-September, Salem businesses present a host of “Haunted Happenings,” announced in the sixty-four-page free magazine touting products, tours, plays, and other opportunities on offer during those weeks. The Chamber of Commerce president proudly notes the more than one million visitors came to the city during the 2024 autumn festivities. Judging from the traffic and the strain on parking, the figure of a million over the seven-week event might this year be exceeded. When welcoming visitors to Salem’s spectacle, the president invokes the city’s past witches as the core component of the fabulously successful event. The statute of actor Elizabeth Montgomery playing the 1960s television comedy witch from Bewitched, permanently on display along Essex Street, playfully invokes the city’s claims to witch history.

Some tourists clearly agree that the event is about what they understand of 1692, judging from the crowds gathered on Salem’s Essex Street pedestrian mall. This blocks-long walking street serves as the epicenter of the lavish phenomenon. Attendees on the September day when I accidentally stumbled into the event tended to be more female than male, with women whose ages ranged from young adult to middle aged dominating the crowd. Many were dressed for the occasion, if not as historic witches, at least with the jewelry associated with New Age or Wiccan sensibilities or else in t-shirts proclaiming a feminist condemnation of witchcraft prosecutions. “They didn’t burn witches—they burned women” captured the sentiment. This militant statement was somewhat ruined for the well-informed historian by the thought that no one was burned at Salem. (That method of execution was used only by Roman Catholics who recognized witchcraft as the religious crime of heresy. The Protestant magistrates at Salem hung witches for civil crimes.) Continuing the colonial theme, some tourists, male and female, wore mushroom-shaped felt hats that were sold along the walking route—with a rounded crown, they were not the classic pointy witch hat of popular culture but instead seemed to be someone’s idea of colonial garb.

Such modest allusions to the colonial past were in the decided minority, however, swamped by the more generic Halloween ambience of the event. Take, for example, the many buskers lining the street. The official magazine showcased those buskers who came out in witch attire, and in doing so they highlighted them out of proportion to their actual presence. Running the gauntlet of Essex Street, I saw a guy in an ape suit, a Plains Indian in full headdress, a werewolf, a Dracula, a Smurf, a Bigfoot, a Jason, a Mario Brother, a Chuckie, a Frankenstein’s monster, a Captain Jack Sparrow, a Hannibal Lector, a Pennywise, and a Predator, as well as multiple characters from Nightmare before Christmas. Although horror was overrepresented in the costumed performers, having a high-end costume to don seemed the only real requirement for joining the ranks of entertainers. A connection to a scary movie was appreciated but clearly not required.

The witches, vastly underrepresented, had been replaced by costume characters from films. The local movie theatre did its part to promote the witchy element, showing the 1993 comedy film Hocus Pocus, starring Bette Midler, Sarah Jessica Parker, and Kathy Najimy. Interestingly, more recent popular film franchises featuring witches, such as Harry Potter and Twilight, were not highly visible, although storefronts selling merchandise related to both did find a place on Essex Street. Although a few people dressed to indicate their solidarity with the executed, they strolled through a party centered more on Halloween than on 1692.

Halloween’s predominance follows the recent trend amplifying that holiday in the U.S. Tours on offer to Salem visitors emphasize ghosts as much as witches (or more so), even proclaiming wrongly in one case that customers could experience what the accusers and prosecutors of witches most feared in 1692, witches and ghosts. Despite the feminist witch contingent in the crowd, the focus rested squarely on Hollywood horror and even on Halloween more generally. That holiday in the U.S. has shifted over the decades. Once a night for children in homemade (or cheap store-bought) costumes who “trick or treated” for candy from their neighbors, it has become a massive event for adults who dress up, go to parties, and spend lavishly on decorations. Indeed, predictions have it that Americans this year will spend an estimated $13,000,000 on Halloween. A chunk of that Halloween spending is making its way into Salem’s coffers, as local businesses use a vague gesture toward colonial-era witchcraft executions to entice Halloween tourists to their city.

So, what is the historian to do? I have long since stopped explaining to people about the burning versus hanging difference between continental Europe and New England, which goes over about as well as trying to tell one’s fellow academics that dashing sea raiders were mostly not pirates or that the term “puritan” had little historical resonance in New England. Salem in October is more an expression of our moment, with its wild consumerism and hodgepodge of dimly understood historical references, with consumer culture masquerading as historical critique.

The witch scare, an event of some significance in its own time, is little understood by popular audiences and is arguably become ever less so as a result of Salem’s “world-famous” autumn party. Efforts at repairing the inaccuracies mounted by local museums such as the Essex Peabody or by one-act plays presenting some version of the history hardly make an impression. The Salem business community has what it has long sought—an extravaganza bringing in tourism dollars, and the Halloween revelers are mostly pleased, even if a few (mostly women) could be heard to grumble about the dearth of witch-related programming.

My final take away was to muse over the most popular interpretation of the Salem witchcraft, that promulgated in the 1974 work Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft by Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum. That work helpfully seated the witch scare in Salem Village and demonstrated how it reverberated out from there. It suggested that the root cause of the villagers’ conflict was the rise of capitalism, with frightened residents fearful of change accusing those who enjoyed some economic success in the new system (or were associated with those who did so). I have always thought that argument weak, as I recently explained in an American Historical Review piece. As a result, it was ironic to see that today, at least, Boyer and Nissenbaum had the right of it: Salem witchcraft, whatever it was about in 1692, today marks the triumph of capitalism. Clearly, in today’s Salem capitalism has won. The witches, for their part, continue to be silenced and misunderstood even as a cascade of money pours into Salem’s coffers.

Further Reading:

Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum, Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1974).

Carla Gardina Pestana, “A Modest Proposal,” Commonplace: the journal of early American life, accessed October 26, 2025, https://commonplace.online/article/a-modest-proposal/.

Carla Gardina Pestana, “Early English Jamaica Without Pirates,” William and Mary Quarterly 71, number 3 (July 2014), 321-360. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5309/willmaryquar.71.3.0321

Carla Gardina Pestana, “The Origins of Witchcraft Crisis 50 Years Later — Paul S. Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum. Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft” American Historical Review 129, number 4 (December 2024), 1751-54. https://academic.oup.com/ahr/article/129/4/1751/7915353

This article originally appeared in November 2025.

Carla Gardina Pestana started her scholarly life studying religion in New England. Since then she has studied other places and topics as well, and teaches at UCLA. As a child, her homemade version of Halloween was her favorite holiday. Her most recent book is a history of Plymouth in its first years and in a broader context: The World of Plymouth Plantation (2020).