Don’t look now, but the country’s money is changing. Really changing. After decades of consistency, the greenback has begun a startling metamorphosis in its appearance. It all began in 1996. Out went the modest busts of the dead, replaced by enormous heads with impossibly high foreheads and hair straight out of an advertisement for Rogaine. The new notes made a fetish of asymmetry. The presidential portraits sidled leftward, and strange and shiny numbers made their appearance on the lower right-hand side of several of the high-denomination bills, printed in a green—or is it black?—ink. And no sooner had we come to terms with the fresh look than the Bureau of Engraving and Printing let loose a new twenty-dollar bill that featured, of all things, a light-blue eagle floating to the left of Andrew Jackson’s head. A pale peach stripe now runs through the center of the bill, and the little iridescent “20” has changed from green to gold. Even the back of the note, which had up until then been left unchanged, was given a sprinkle of tiny yellow “20s,” making the White House look as though it has been encircled by a swarm of angry bees. Any user of the once-staid United States currency would be entitled to ask: What’s going on here?

While it is tempting to ascribe our money’s makeover to American envy about the new Euro notes, the threat of counterfeiting was the real impetus for the change. After some seventy years in which the look of the greenback changed very little if at all, the country is adopting a novel look for its currency in the hopes it will deter a new and technologically savvy generation of criminals. But if history is any guide, the Treasury Department has an uphill fight ahead of it; counterfeiters have a knack for circumventing almost any obstacle put in their way. That said, the challenges the government now faces pale in comparison to the monetary misery of an earlier epoch, when counterfeiting assumed epidemic proportions, eventually becoming symbolic of a crisis of confidence in the nation’s currency, and perhaps in its emerging economic culture as well.

It has been called the “golden age of counterfeiting” by one historian. Between the Revolution and the Civil War, counterfeiters operated with impunity throughout the United States. Many became folk heroes for their exploits, and more than a few observers in the fledging republic feared that the economy would drown in a flood of bogus currency. Newspapers of the day published breathless warnings of counterfeits circulating throughout the country. An issue of Niles’ Weekly Register from 1818 warned of a single fraudulent emission of notes, telling its readers that “more, much more, perhaps, than a million of dollars in counterfeit and altered notes, have very recently been manufactured.” The warnings only intensified as the decades passed, and by the early 1860s, the New York Times concluded that “there are very few persons, if any, in the United States, who can truthfully declare their ability to detect at a glance any fraudulent paper money . . . In spite of all precautions,” the paper observed, “every merchant has his pile of counterfeit money, and his hourly fear of having it increased.”

The antebellum era’s counterfeiting problem was a consequence of the nature of the money supply at this time. There is a tendency to assume that the greenback is a timeless creation, that the nation-state has always taken the lead in issuing and safeguarding the currency. Nothing could be further from the truth. Prior to the Civil War, the United States exercised little control over the money that circulated within its borders, having abdicated that responsibility decades earlier.

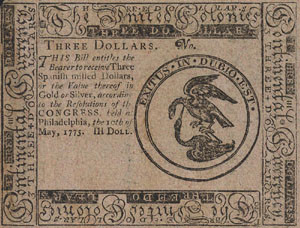

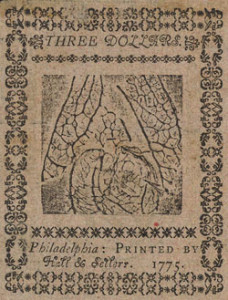

In fact, the roots of the problem date back at least to the previous century, when the colonists began issuing paper money contrary to the wishes of the imperial authorities. They had good reasons: in a specie-poor economy, it was absolutely necessary to have some circulating medium with which one could transact business. The British passed laws banning the practice, but to no avail. And a curious North American tradition of monetary democracy—the right to “make money,” literally—was born, one that reached its apotheosis during the American Revolution, when the fledgling nation financed its independence with a flood of paper money.

Constitution marked an attempt to reverse this trend in that it forbade individual states from issuing “bills of credit.” Yet at the time, those three words had a very specific meaning: the paper debt of governments (and occasionally individuals) issued as legal tender. Paper money issued by state-chartered banks, or “bank notes,” did not have the same pretensions, being nothing more than surrogates of money, slips of paper that could, in theory, be converted to real money (specie) when presented at the counter of the issuing bank. Within a few years of the ratification of the Constitution, a growing number of states had chartered banks and other corporations that could issue their own money. The upshot was not, perhaps, what the framers of that document had in mind when they attempted to “shut and bar the door against paper money,” in the words of one delegate. While only a handful of corporations issued their own notes in the 1790s, approximately 250 did by 1815, and by 1830, the number climbed to 330. Ten years later that number jumped again to 901, dipped in the early 1840s, and then skyrocketed again in the 1850s. By 1860, some 1,562 banks, or “rag manufactories,” as one critic called them, churned out a dizzying stream of colorful bits of paper.

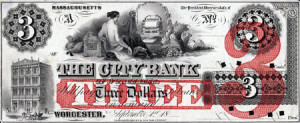

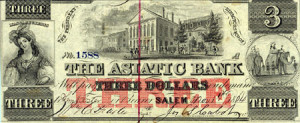

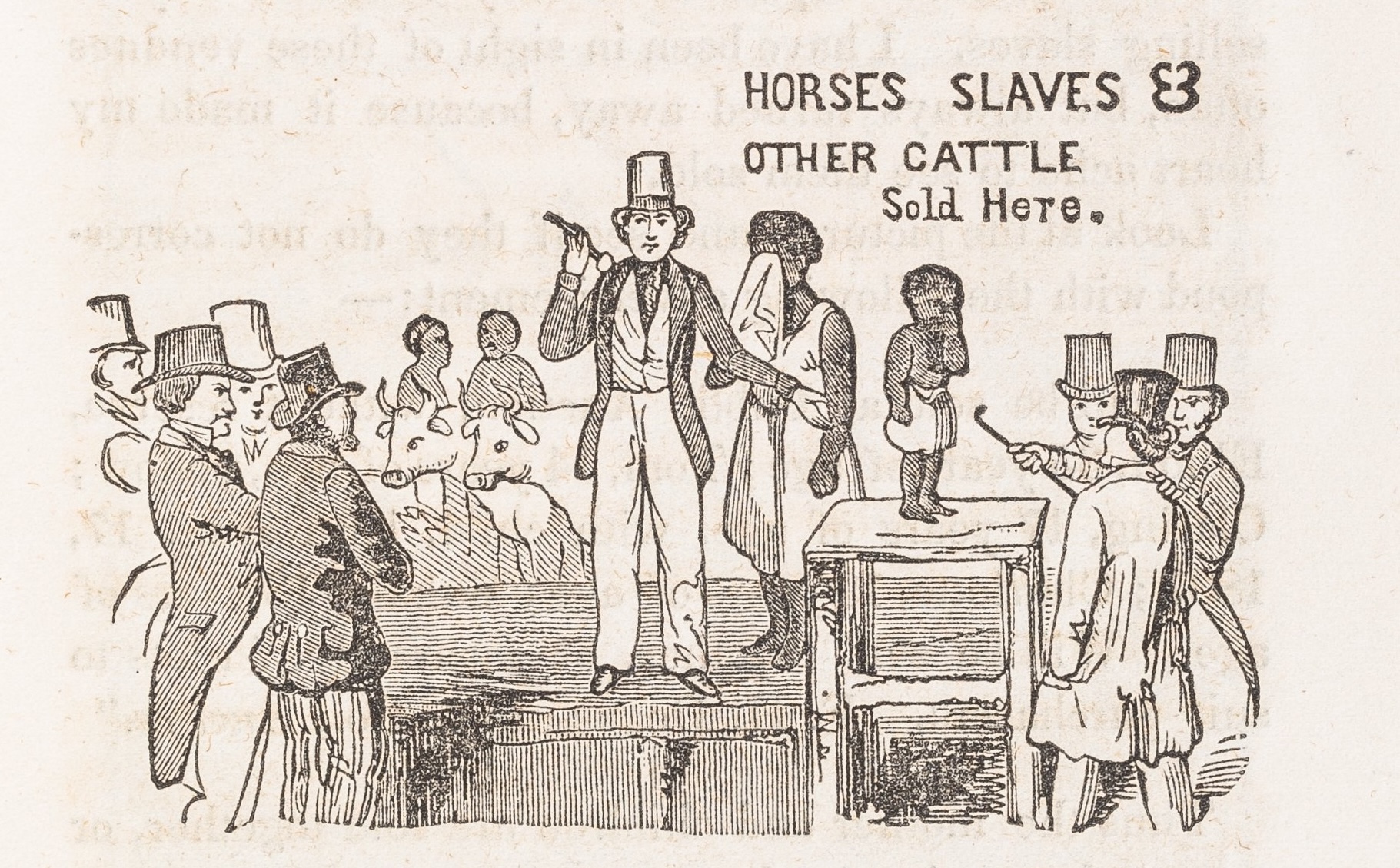

Banks, left to their own devices, did not issue their notes in concert, nor did they subscribe to a uniform design. As a consequence, the look of an individual bank’s notes depended on criteria as disparate as the personal preferences of a corporation’s board of directors, the regional or commercial allegiances of the institution, and the relative cost of engraving the pictures, or vignettes, on the bills. Antebellum bank notes thus portrayed a bewildering array of individuals and events drawn from history, mythology, and fiction: Lafayette, Martha Washington, Saint George and the Dragon, Poseidon, Penn’s Treaty with the Indians, Archimedes, Santa Claus—even contemporary figures like P. T. Barnum, Lord Byron, Jenny Lind, Daniel Webster, and yes, Andrew Jackson. Other notes depicted allegorical figures representing commerce and industry, or stock figures such as slaves, farmers, tradesmen, and sailors. Still others showed ships, railroads, canals, wharves, shops, and other symbols of commerce. With every bank commissioning money of its own design (and in denominations, sizes, and colors of its choosing) more than ten thousand different kinds of notes bobbed up and down in the streams of commerce by the late 1850s, continually changing hands and baffling the uninitiated. Even the phrenologist George Coombe, no stranger to reading appearances, marveled in 1841 that “it has become a science nearly as extensive and difficult as Entomology or Conchology, to know the value of the currency.”

As Coombe recognized, the simple act of reading these notes posed a substantial challenge, one that grew more acute with every passing year. Early on, when only a few banks issued notes, it was relatively easy to remember the different designs, which made detecting counterfeits—or at least poorly rendered counterfeits —a relatively simple task. But as the decades passed, the market economy took root in the most remote corners of the new nation. Where the market went, banks and bank notes followed. And within the widening compass of capitalist relations, these monetary hieroglyphs drifted ever further from the institutions that issued them, making it increasingly difficult to keep track of the currencies in circulation, much less spot a fake.

It staggers the imagination to comprehend the extent and ubiquity of counterfeiting during the antebellum years. One estimate in 1862 observed that “out of 1,300 bank note issues, but 100 are not counterfeited,” and counted some 5,902 different kinds of bogus bills. Others claimed that fraudulent bills accounted for upward of a tenth, a quarter, or even a half of the paper money in circulation. Many of these fakes went beyond simple imitations. Instead, counterfeiters exploited people’s unfamiliarity with the currency by issuing notes that bore no resemblance whatsoever to the genuine article (spurious notes). Others produced notes with their title, locality, or denomination extracted and a new one put in its place (altered or raised notes). Still others dropped all pretense of authenticity, and arrogated the banking function, producing notes that sounded plausible (from the Merchants’ Bank of Utica, for instance), but which had no parallel outside the counterfeit economy. Such notes, while deemed counterfeit, blurred imperceptibly into yet another category of fraud, the notes of so-called “wild-cat” banks—institutions founded by unscrupulous financiers in remote areas for the express purpose of making it difficult, if not impossible, for the notes to be exchanged for gold and silver. Counterfeiting thus existed on a continuum of fraud where the dividing line between the solid and the sham vanished upon close examination.

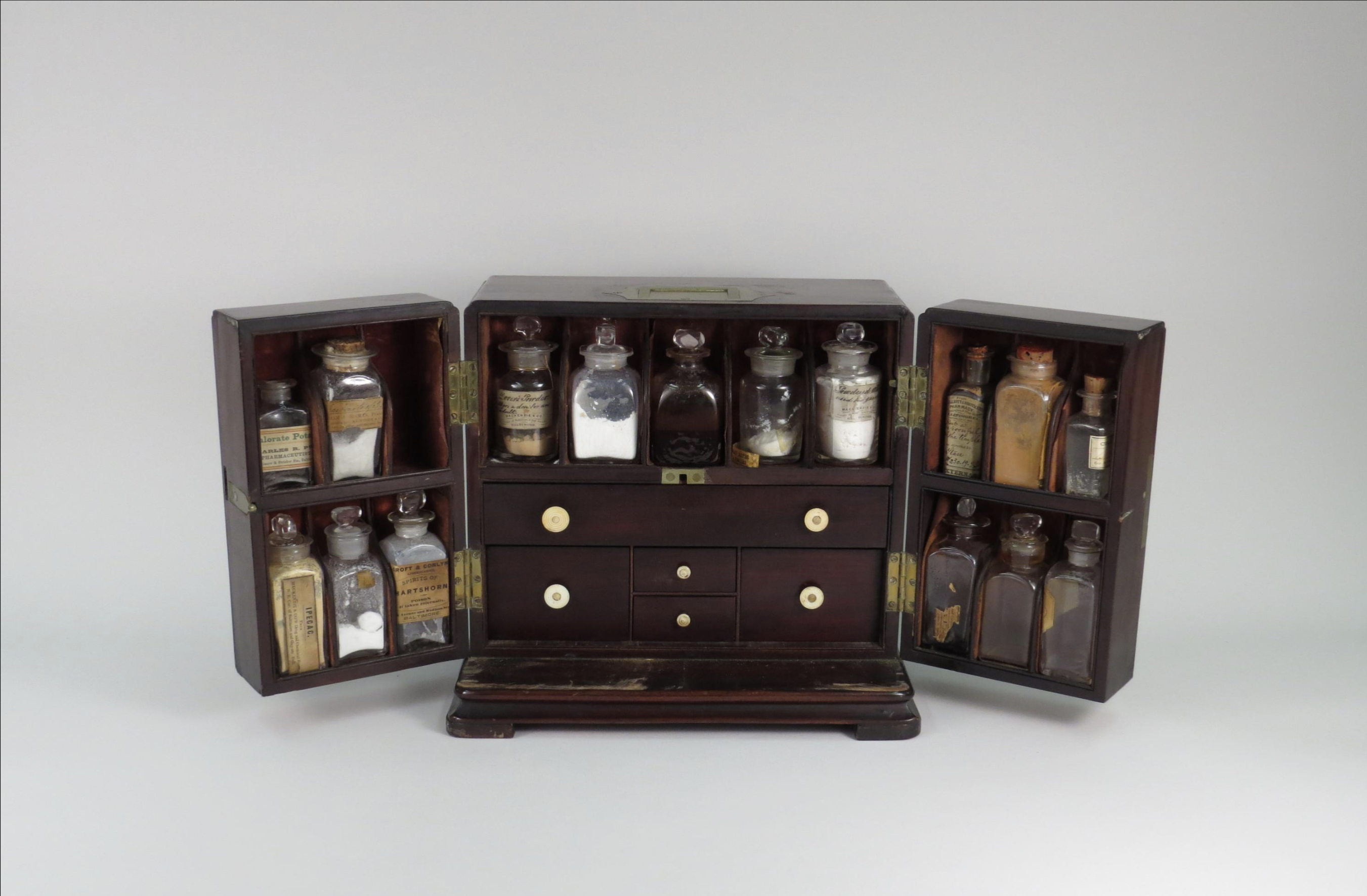

While the problem of counterfeiting at this time grew out of the diversity of the money supply (something that is no longer an issue), there are more than a few echoes of the past in the present battle against counterfeiting. Take, for example, the growing availability of technologies that can be turned to the counterfeiters’ ends. In the early nineteenth century, new engraving and printing techniques enabled bank-note engravers to produce infinite copies of the plates and dies used in the manufacture of notes, a process known in the bank-note engraving trade as siderography. All the elements of a bank note—the border, the pictures, or vignettes, and the denominations of the bills or names of the banks—could be copied endlessly with perfect fidelity. More than a few counterfeiters never went to the bother of engraving imitations—they could often get copies of the real thing. Add to that the discovery of chemicals and compounds capable of erasing and altering notes, and perhaps most important of all, the invention of photography in 1847, and the ease with which notes could be copied, altered, and otherwise forged grew exponentially between 1800 and 1850.

And now? A similar wave of cheap and easy-to-use computer hardware and software—color photocopiers and printers, digital scanners, and image manipulation software such as Photoshop—has flooded the market, enabling anyone with a bit of computer expertise and a criminal mindset to make their own money. Like the technological innovations of the past century, this equipment does not require extensive training to use, and is cheap and widely available for use at home, schools, printers’ shops, and a host of other venues.

The government’s response has been swift, if predictable. Seeing the writing on the wall—and fearing the printing in the wallet—the Treasury Department funded a National Research Council study in 1993 to investigate possible counterfeiting deterrents. The research team put safety features through countless tests, probing for weaknesses, trying to find ways to outwit the latest technology. The ongoing makeover of our money is a product of that first study, and will add about two cents to the cost of producing each note, a cost, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing assures us, that is to be defrayed by interest on government bonds held by the Federal Reserve. Fear not, taxpayers!

While the new designs may seem exotic and strange, there is nothing particularly new about any of them. The use of special inks, complicated watermarks, complex designs, and denomination-specific safeguards (such as printing “20” dozens of times on a bill) has a long and illustrious history. In the early republic, bank-note engravers and mechanics filed scores of patents designed to frustrate counterfeiters using precisely these devices. Want some anticounterfeiting paper? A proposal from 1822 that calls for the use of paper dyed with blue indigo might be of help. Or would special inks be of interest? Any of the different two-toned black and green inks developed in the 1850s would be of use. Watermarks? They went into widespread use in the early nineteenth century, with the manufacturers of bank note paper taking the lead. All of these anticounterfeiting measures have a history, and a rather long one at that. And in the past, counterfeiters have always managed to circumvent these obstacles. Indeed, they have an incentive to do so. The most dangerous counterfeit—and the one that is most likely to pass without much trouble—is one that perfectly imitates some safeguard the public believes to be inimitable.

It does not bode well for the Treasury Department. Yet one thing our government has going for it is that it need only protect a limited number of designs. Indeed, the strength of today’s money supply lies not with its diversity, but with its simplicity. With only six different types of bills in circulation, it is relatively easy to remember what face goes with what denomination, though more than a few people will struggle to remember when posed that question. Their amnesia is less a function a cultural illiteracy (or poverty) than a testament to just how secure they feel about the currency and how little they need to question the underlying value of these scraps of paper. We do not much read money any more. The bill is in our hands, it is green, and it has a number on it: that is all we need to know. Its virtue is its familiarity. Which is why the government has introduced the new anticounterfeiting measures over the space of close to decade, and in a series of very slow, staged steps. “The currency still has a familiar American look,” states the Bureau of Engraving and Printing on its Website. “The size of the notes, basic colors, historical figures and national symbols are not changing,” the Bureau notes reassuringly. “New features were evaluated for their compatibility with the traditional design of U.S. currency.”

That is debatable, given how they have tarted up Andrew Jackson. But the intent is clear: do not make radical changes or you risk shaking people’s faith in the paper in their wallets. The greenback has become so synonymous with the financial strength of the United States both at home and abroad that radically altering the design is dangerous. Such changes are only welcome when a nation wants a new start (Iraq, for example), or in the case of the European Union, when an entire region wants to carve out a new identity. But in general, preventing a few counterfeits is not worth the erosion of confidence that accompanies the wholesale revision of the symbols and signs that give our money its meaning. After all, in the absence of a gold standard, it is all based on confidence.

By contrast, the banks that issued notes prior to the Civil War worried little about what a change in the design of their notes would mean. If anything, a more expensive and artfully engraved note was taken to be symptomatic of the bank’s financial well being, while a poorly engraved or simple note could indicate a lack of resources and commitment. Individual banks and other note-issuing corporations did not have to shoulder the burden of national sovereignty; they had only to worry about their own interests and their own profit.

Despite all the counterfeiting, that system worked relatively well: the nation had a sufficient circulating medium to meets its insatiable need for credit. And while the system collapsed with some regularity—in 1818 and 1837 most dramatically—resulting in the suspension of specie payments if not national bankruptcy, it does not appear to have slowed down the pace of growth. Indeed, if anything, the sprawling system of state-chartered banks and the money they issued contributed to the nation’s economic ascent. The federal government played little role in any of this in the early nineteenth century, minting some coins and chartering the Bank of the United States, but otherwise steering clear of direct involvement in the monetary system. That process of disengagement only intensified after Jackson’s “Bank War” in 1832-33, which effectively transferred control of the money supply from the Bank of the United States to corporations chartered by the individual states. What prevailed in the early United States was not the most dignified monetary system, but it did work, in part because so many people were willing to suspend disbelief and accept otherwise worthless pieces of paper in the course of business. It was an era in which the distinctions between the real and the counterfeit had yet to coalesce.

But eventually they did coalesce, which brings us full circle back to the efforts of the federal government to protect the currency from counterfeiters. Short of funds during the Civil War, the North turned to the printing presses to finance the war, issuing the money that quickly became known as the greenbacks. Within a few short years, the convergence of the country and the currency was complete, and the older system of the state-chartered banks and their notes was swept away in a flurry of nationalist legislation, replaced by a uniform currency issued by the federal government and a select number of so-called “national banks.” The nation-state now had a vested interest in protecting the currency, and a new national policing agency was established to prosecute counterfeiters to the fullest extent of the law. Indeed, before the Secret Service began protecting the president, its members spent most of their time protecting the money supply from fraud, imposture, and insult. There is something telling about the fact that the greenback was considered a national symbol more deserving of protection than the head of state through much of the Gilded Age. That eventually changed, but even today, the job of protecting the money supply is central to the mission of the Secret Service.

By the early twentieth century, the Secret Service had largely succeeded in eradicating counterfeiting, and an era of almost unquestioned confidence in the greenback began. Little could those officers have imagined the present crisis of authenticity triggered by the proliferation of digital imaging. And so now the government has apparently come to the conclusion that a police force alone cannot protect the currency. It must harness technology as well. Today, as in the early republic, there is the hope that a splash of color, some watermarks, and a new look will frustrate the counterfeiting community. Perhaps, but as the bankers of the early republic could attest, it is one thing to make money more difficult to copy; it is altogether another matter to make it impossible to imitate.

Further Reading:

There is no serious history of counterfeiting in the United States, though Lynn Glaser, Counterfeiting in America: The History of an American Way to Wealth (New York, 1968) is not without its merits. Also helpful, if a bit earlier in focus, is Kenneth Scott, Counterfeiting in Colonial America (New York, 1957). On counterfeiting and the rise of the Secret Service, see David R. Johnson, Illegal Tender: Counterfeiting and the Secret Service in Nineteenth-Century America (Washington, D.C., 1995). For more on the rise of national monetary systems, consult Eric Helleiner, The Making of National Money: Territorial Currencies in Historical Perspective (Ithaca, 2003).

This article originally appeared in issue 4.4 (July, 2004).

Stephen Mihm is an assistant professor of history at the University of Georgia. He is presently writing a book about counterfeiting and capitalism in the nineteenth-century United States.