There is a classic early episode of The Simpsons in which the denizens of Springfield eagerly prepare for their town’s bicentennial celebration. As part of a school assignment, precocious eight-year-old Lisa Simpson decides to investigate the exploits of her town’s founding father, Jebediah Springfield. She begins with the best of intentions, hoping to lionize a local hero. After some vigorous historical sleuthing, however, she uncovers a terrible truth: the man universally celebrated as a fearless pioneer of the western plains was actually a “murderous pirate” named Hans Sprungfeld. Hardly a patriotic hero, he was an assassin and a fraud who had tried to kill George Washington and whose tongue had been “bitten off by a Turk in a grog house fight.”

The Amistad case is usually presented as a key chapter in American history, a commentary on slavery as a distinctly American dilemma. Virtually all scholars who discuss the event pay little or no attention to the fate of the captives after their return to Africa, and when historians do attempt some accounting of the activities of the survivors, the story remains vague or incomplete.

Needless to say, Springfield residents are dismayed by Lisa’s findings and refuse to believe them. Her teacher gives her an F for “dead-white-male-bashing.” Even local historian Hollis Hurlbut (voiced by the marvelously deadpan Donald Sutherland) refuses to accept the truth. Undeterred, Lisa persists in her effort to defrock the villainous Sprungfeld. She convinces authorities to exhume his corpse and discovers new evidence to corroborate her theory. But, on the cusp of revealing her proof to the world, Lisa has a change of heart. She realizes that the legend of the hometown hero has united her small community. The myth itself, it turns out, is worth preserving, and she abandons her revisionist project. Although the moral message is not one that most professional historians would embrace, it speaks to a larger truth. Those looking to reappraise the careers of treasured celebrities had best tread lightly; iconoclasm is not always in vogue.

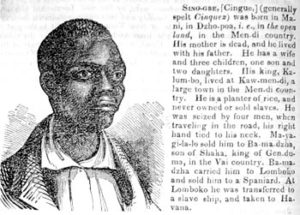

As leader of the 1839 Amistad slave revolt, the man known as Joseph Cinqué has earned a rightful place in our pantheon of heroes. The general outline of his story is well known. Kidnapped in Mende (in the hinterland of what is now Sierra Leone) and carried across the Atlantic to Spanish Cuba, he was one of many victims of an illegal but still thriving international slave trade. After his arrival in Havana in the summer of 1839, he and fifty-two other Africans were transferred aboard the schooner Amistad, destined for a lifetime of forced labor on Cuban plantations. Cinqué and some of his fellow captives managed to seize control of the vessel and attempted to sail home but were intercepted by the United States Navy as they veered into southern New England. Black and white abolitionists championed the rebels’ cause over a period of several years, and after a series of legal challenges that culminated in a dramatic Supreme Court showdown, the survivors were finally allowed to return home.

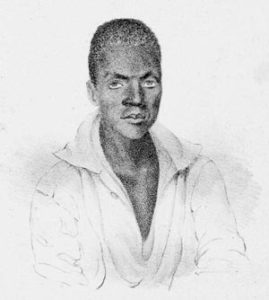

The informal representative for the Amistad group during their stay in America, Cinqué became one of the most celebrated Africans of the nineteenth century. He has been immortalized in portraits and novels and dominates the screen in a multiple award-winning film by Steven Spielberg (fig. 1). Like the larger-than-life monument to Jebediah Springfield featured prominently on the Simpsons’ town green, a fourteen-foot bronze statue commemorating his bravery stands just blocks from my apartment, in downtown New Haven, Connecticut. So, I must admit, I felt more than a little uneasy when I discovered evidence that appeared to substantiate rumors that Cinqué had participated in the slave trade upon his return to Africa. Perhaps Lisa Simpson was right. Perhaps old ghosts are best left undisturbed. Yet, I could not resist the urge to investigate this troublesome accusation. Especially now, in the aftermath of the two hundredth anniversary of the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade, there is no better time to reopen old controversies and revisit longstanding myths.

Over the past year, I have been investigating the life of ex-convict and radical antislavery activist George Thompson, including his role as director of the American mission station established in West Africa as an extension of the Amistad victory. Knowing that most of the Amistad survivors had deserted the mission long before Thompson’s arrival in the late 1840s, I suspected they would play only a very minor part in my story. But a brief reference in his memoir, the humbly titled Thompson in Africa, caught my attention. Tucked away in the middle of page twenty-four, following an account of his dinner with the governor of Sierra Leone and just before an update on his aggressive campaign against intoxicating drinks, Thompson announced that the famous Cinqué had been married in the house of an elderly native. According to Thompson, he had “conducted badly” thereafter and left the colony for Jamaica. What could this mean? Thompson was a prolific diarist; his published letters and journals alone amount to over two thousand pages. But I could not find much beyond this stray comment.

The 1839 Amistad uprising was one of only a few truly successful slave revolts in the history of the Atlantic World, and the Supreme Court trial that ensued is now widely recognized as a pivotal event in early American history. The brief reference to Cinqué in Thompson’s memoir had piqued my interest. So, like any curious student, I hurried to the nearest library to check out the existing scholarly literature. What I found was both disappointing and perplexing. Very little is known about Cinqué. The details of his life both before and after his capture remain obscured behind a haze of rumor and speculation. Even his true name is unclear. The Latinized version most popular during his lifetime was concocted by white slave traders in order to mask their illegal activities. His abolitionist allies tended to refer to him as “Cingue” or “Cinque,” while some modern historians prefer the Africanized “Sengbe Pieh.” (I have chosen to use the former in the interest of historical accuracy and because he seems to have presented himself as such in correspondence with his abolitionist friends.) These ambiguities stem from a biased and incomplete historical record, but they also reflect a deeper problem in the historiography of slavery.

Despite the widely heralded international turn in historical studies over the past two decades, the entire African phase of the Amistad revolt has been, and continues to be, ignored. The Amistad case is usually presented as a key chapter in American history, a commentary on slavery as a distinctly American dilemma. Virtually all scholars who discuss the event pay little or no attention to the fate of the captives after their return to Africa, and when historians do attempt some accounting of the activities of the survivors, the story remains vague or incomplete. Authoritative texts published as recently as 2006 devote only a few sentences to the lives of the former captives and get a number of the basic facts wrong, including the location of Mende (Cinqué’s homeland) and the number of white missionaries who accompanied the rebels upon their return. Most mysterious of all was the question of what had happened to their illustrious leader; no one seemed to know.

Nine years ago, preeminent Amistad scholar Howard Jones published an article in the Journal of American History that directly confronted Cinqué’s activities in Africa. Jones was especially concerned with rumors that the rebel hero had engaged in slave trading upon his return and traced such accounts to an obscure retrospective issued in the 1940s. He argued that there was not one shred of documentary evidence that could corroborate the story, and most experts today seem to agree. Yet the bulk of Jones’s research focused on books published in the twentieth century by novelists and academics. The disparaging remark in Thompson’s memoir suggested that Cinqué was the object of controversy at a much earlier date.

I returned to the library. A dissertation by the late Clifton Johnson, founding director of Tulane University’s Amistad Research Center, offered a wealth of information on the establishment of the American mission station in West Africa. Johnson concluded that “some” of the former captives had engaged in the slave trade and “proved a great hindrance to the mission.” But his primary source was the same dubious text identified by Jones—parts of which were noticeably plagiarized. Research published in 2000 by English professor Iyunolu Osagie offered a more sympathetic overview of the experience of the repatriated Africans and speculated that white authorities had labeled Cinqué “a ‘bad nigger’ because he did not cooperate with the missionary agenda.” But this only presented another dilemma. If the accusations of slave trading were utterly false, as Jones and Osagie maintained, what had prompted them? Could they have been conjured out of thin air simply because Cinqué refused to join the mission? Or did they have some basis in reality? I decided to dig through the early records of the Amistad mission to see for myself.

After their landmark victory in the United States Supreme Court in the spring of 1841, most of the former captives of the Amistad were eager to return home, and the scores of black and white activists who had aided their case were eager to comply with their wishes. Black abolitionists, in particular, interpreted the Supreme Court victory as a providential calling—a sign from God to spread the antislavery gospel in Africa—and led the effort to carry this message back across the Atlantic. Joining forces with the white, mostly Congregationalist, leadership of the original Amistad Committee, they formed the nucleus of what would eventually become the American Missionary Association. Their goal was to establish an antislavery outpost somewhere in the vicinity of Sierra Leone, with the Amistad captives as its charter generation. Three white missionaries and two black assistants were recruited for the job. But when they all piled on board the Gentleman in New York harbor in late November 1841, the relationship between the thirty-five former captives and their would-be benefactors was tenuous at best.

During the two-month voyage to Sierra Leone, the recently emancipated Africans worried that their white friends might abandon them to the captain for “a barrel full of money” and kept a close eye on the night sky and the ship’s compass to ensure they were following the proper course. They had good reason to be suspicious—when they had seized the Amistad three years earlier and attempted to return home, the surviving crew had secretly maneuvered the ship in the opposite direction at night. Tensions ran high as the group neared the African coast. European privateers suspected the Gentleman was a slaver, and it narrowly escaped capture when it stopped for supplies at São Tiago in the Cape Verde Islands. When the group finally arrived in Freetown, Sierra Leone, the hunt for friends and relatives began in earnest, and most of the Africans left the colony after a short period of time. Cinqué, who had been reunited with his brother at Freetown, remained in the area and helped the missionaries explore the coast for a suitable location for the mission.

Despite high hopes for a stable population of pious, industrious converts, the mission community began to disintegrate almost immediately. Problems agreeing on a site for the mission were made worse by conflicting ethnicities. Although commonly referred to as “the Mendians” by white Americans, in reality, the Amistad survivors were composed of at least six different West African ethnic groups, and not all wanted to remain in the same place. Mende territory, assumed to be the ideal location for a mission outpost, was buried deep in the interior, well beyond the sphere of British protection and surrounded by war and the slave trade. It took two years before a permanent base was established at the village of Kaw-Mendi in the Sherbro region of West Africa, 150 miles southeast of Freetown and about “two days walk” from Cinqué’s home.

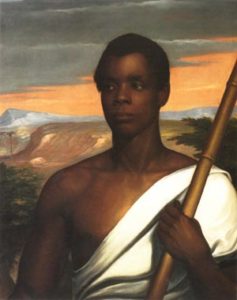

The white missionaries had difficultly maintaining their authority over the remaining Africans. The Christian piety and discipline that had seemed so promising among some of the captives during their stay in America quickly melted away. One of the survivors got into a violent brawl with locals and was almost shot. Another began sharing mission supplies with his paramour. Yet another became dangerously intoxicated at a friend’s funeral. While preparing to leave the United States, church authorities had informed the missionaries that the Mende had no real “system of religion,” that they were essentially blank slates waiting to be inscribed by the benevolent hand of Christian Civilization. So the agents were shocked to find so many reverting to “heathen” practices virtually overnight (fig. 2). William Raymond, a white abolitionist who supervised the missionary operation for nearly six years, wrote home that it might “be better for me and the mission if they should all leave me, and I had another set of men.” Not long afterward, he dismissed all but four of the remaining group from his care, “on account of their bad behavior.”

The most famous of the Amistad survivors proved especially vexing for the missionaries. According to reports published by the antislavery press, Cinqué had been living with his father and working as a rice farmer when he was kidnapped and sold across the Atlantic (fig. 3). The veracity of these claims remains an open question; other accounts insisted that he was a prince or that he was a slaveholder who had trouble paying off his debts. Whatever the case, Cinqué proudly embraced his role as leader of the rebellion and, because of his celebrity status, acted as an unofficial spokesperson for the rest of the group. Audiences across New England declared him “a powerful natural orator … born to sway the minds of his fellow men,” and white abolitionists imagined his potentially illustrious career as “a preacher of the cross in Africa.” But their unmitigated adulation only bred disappointment.

When he left New York in November 1841, Cinqué assumed he would be in charge of the entire expedition and that the missionaries and all their supplies would be under his control. He decided to pursue an independent course when he realized that this would not be the case. Evidence from the antislavery press suggests that he became a conventional merchant, probably trading rum, tobacco, and various kinds of local produce. He did remain in the vicinity, however, and clashed openly with the white missionaries. William Raymond thought he was “both dishonest and licentious” and was not pleased when he attempted to carry away some of the younger Amistad survivors for a ritual clitoridectomy, or female circumcision. A major confrontation was avoided when the young women, who remained closely attached to the missionaries, refused to leave. Raymond declined to support the woman Cinqué had married in Freetown and at one point told him to remove all of his belongings from a communal home owned by the mission. Another missionary blamed Cinqué for causing “most of our troubles.”

After the first few months, as the missionaries gradually accepted the fact that Cinqué would not be joining their settlement, this kind of criticism dropped off precipitously. Even William Raymond was reluctant to completely dismiss Cinqué. During a brief trip home in the summer of 1843, he pointed out that the celebrated insurrectionist had played a key role in securing the land for the mission at Kaw-Mendi and seemed to approve of his entrepreneurial activities along the West African coast. Such statements were self-serving for the missionaries, who were in constant need of financial support. But they also signal a growing rapprochement with the Amistad survivors as the missionaries shed their initial optimism.

The evidence provided by George Thompson corroborates reports by Raymond and others that Cinqué left the colony for Jamaica sometime around 1845. Thompson’s reference to his “bad conduct” is less clear but probably reflected Cinqué’s earlier troubles with the white missionaries. Thompson, who arrived in West Africa in May 1848, probably never met the hero of the Amistad. It is unlikely that he had read reports about Cinqué’s behavior before leaving—he was serving out a twelve-year prison sentence for aiding fugitive slaves during this period. Still, he must have heard stories about Cinqué from the natives or the small population of British colonists.

The true meaning of Thompon’s statement remains open to interpretation. To “conduct badly” could mean any number of things for an abolitionist missionary operating in West Africa in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. During his tenure at Kaw-Mendi, Thompson punished native congregants for everything from Sabbath breaking and petty theft to adultery and homosexuality. More than a few of the mission residents were excommunicated for holding slaves, although it is not clear whether any of these were Amistad veterans. Many years after Cinqué’s disappearance, the African convert William Brooks Tucker left the mission and became involved with the slave trade. He was one of Thompson’s star pupils at the time, and it is possible that his story was later incorporated into the Amistad mythos alongside discussions of Cinqué. But it is impossible to know for sure.

In order to better understand Cinqué’s possible connection to the slave trade, it is necessary to take a much closer look at the world he and the other survivors encountered upon their return. West Africa was a region dominated by centuries-old indigenous cultures but profoundly altered by contact with the broader Atlantic World. The Europeans who set up makeshift slave clearinghouses, or “factories,” along the coast held tremendous financial and political power in the region and did extensive business with indigenous traders. When William Raymond moved the Amistad mission from Sierra Leone to Kaw-Mendi in 1844, he was shocked to discover that a Spaniard named “Luiz” was operating a large slave-trading factory just downriver. In fact, Luiz had sold many of the original Amistad captives, and he pressured the local chieftain to wage war against the American mission.

The Spaniard faced fierce opposition from Raymond. The twenty-nine-year-old missionary had been expelled from Amherst College for his uncompromising abolitionism and had cut his teeth working among fugitive slaves in Canada. He wasted no time establishing Kaw-Mendi as an antislavery sanctuary, even using mission funds to redeem captives from the surrounding countryside. With Raymond’s help, the British eventually dislodged the factory and expelled Luiz. Raymond purchased the friendship of the local chief for a considerable quantity of cloth and tobacco shortly thereafter. But he had been lucky. He was vastly outnumbered and almost certainly would have been kidnapped or killed if the Royal Navy had not intervened. A decade later, with British forces redirected toward the Crimean War, the coastal slave trade continued to thrive and large-scale slave plantations were established in the area surrounding Sierra Leone.

It is not hard to find examples of native complicity in the slave trade. The market in human lives was part of an international system of unfettered greed in which both Europeans and Africans conspired to exploit the less fortunate. Slavery was ubiquitous along the West African coast throughout the nineteenth century and played an integral role in the local economy (fig. 4). So it is certainly plausible that Cinqué and the other survivors had at least some contact with human trafficking. For ambitious merchants of all colors, the slave trade was often the quickest route to wealth. And an increasingly global economy only amplified the realm of opportunity. Twelve human beings could be purchased for just one large barrel of tobacco outside Sierra Leone and resold to planters in Cuba or Brazil for many times their original price.

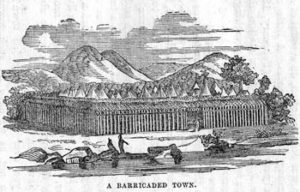

The British Empire’s efforts to suppress the transatlantic slave trade had little more than symbolic impact on the domestic market. Indeed, most of the Amistad survivors were in serious danger of being re-enslaved if they ventured outside British-controlled Freetown. This state of affairs led to a maddening cycle of enslavement and redemption, as scores of former captives left the colony in search of lost family members and friends. “Some Mendians have been sold into slavery,” wrote American missionary James Steele, “then captured and brought here—then they have gone back, been sold, captured and brought here a third time.” The effect of the interior trade was so deeply ingrained that the missionaries could read it in the local architecture. Bucolic towns and villages had evolved into elaborate fortresses surrounded by deep trenches and accessible only by narrow passageways. Some featured double rows of walls topped with thick layers of brush and studded with small openings so that musketeers could fend off invading war parties (fig. 5).

Raymond’s settlement at Kaw-Mendi provided a certain degree of protection for those who agreed to live by its rules. But, for everyone else, it was almost impossible to avoid choosing sides in the endless civil wars that fueled the domestic slave trade. In November 1845, Raymond reported that James Covey, the sailor and former slave who had served as an interpreter during the Amistad trials, had allied himself with a local warlord and was participating in a slaving expedition. Some of the Amistad survivors found themselves on opposing sides of the same conflict. During an attack on the West African town of Mperri, Covey and Kinna (alias Lewis Johnson) were arrayed against former captives Fuliwa (George Brown), Sokoma (Henry Cowles), and Sa (James Pratt). Despite the protestations of his friends, Sa was taken prisoner and killed after the battle. It is not difficult to imagine Cinqué becoming embroiled in one of these brutal and unpredictable feuds. The situation had become so extreme by the end of the decade that one of the American missionaries published a letter in the National Era suggesting that the Amistad captives be renamed “the Amistad capturers.”

Without any concrete data tying Cinqué directly to the slave trade, however, the case remains highly speculative. In fact, the deeper I researched, the more I realized that there is substantial evidence indicating he is completely innocent of the charge. An unpublished letter, penned by white activist Hannah More and buried deep in the archives of the American Missionary Association, is especially significant. Originally a schoolteacher working among Native Americans on the western frontier, More journeyed across the Atlantic in the early 1850s to support George Thompson and the other abolitionists in West Africa. There she encountered a number of the Amistad survivors and used the wedding celebration of former captive Sarah “Margru” Kinson to compile an oral history of their ordeal. The survivors recalled their capture, rebellion, and emancipation in vivid detail for More. Most importantly, they continued to celebrate Cinqué. Some had even committed parts of his speeches to memory and were able to recite them verbatim. There was no mention of any later betrayal.

Diehard skeptics might argue that these men and women had good reason to forget such negative or harmful activities. As the late Carl Sagan once said, “The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” But, in this case, the silence of both published and unpublished documents seems highly unusual. Although antislavery boosters in the United States preferred to emphasize the mission’s small successes, they were remarkably candid about its difficulties, and there appears to be very little censorship of the many detailed reports issued by the white missionaries throughout the 1840s. Worried about creating a bad impression on his donors, Amistad Committee member Lewis Tappan admitted a temptation “to suppress part of this intelligence”—his very own Lisa Simpson moment. But, to his credit, he concluded that “the TRUTH ought to be communicated to the public.” Reports of the ritual circumcision debacle and Raymond’s frequent arguments with Cinqué were published and circulated in full, as were the occasional problems with the other Amistad veterans.

If Cinqué had become involved in the slave trade to any great extent, such juicy news almost certainly would have found its way into the missionaries’ voluminous correspondence. Assuming there was a conspiracy to hide this information for political gain, the matter would have to be discussed between the missionary agents and their supervisors in America. Yet none of their field notes contain so much as a hint that Cinqué was trading anything other than produce during his time in Sierra Leone. Even opponents of the antislavery movement, who eagerly pounced on the news of Cinqué’s relapse into heathenism as proof that the mission had failed, said nothing about his participation in the slave trade. Considering the ferocious intensity of the conflicts over slavery and abolition throughout the nineteenth century, it seems strange that they would neglect to mention it.

So what does all this mean? It is easy to see how the surviving evidence, the scattered correspondence, the brief journal entries, the cryptic allusions to “bad behavior,” could lay the groundwork for later rumors and allegations. But even if the charges against Cinqué are entirely bogus, they are rooted in real historical conflicts. The struggle of the white missionaries to control the Africans in their charge provided the immediate context in which such rumors could take hold and spread. The abolitionist agents and their supporters in America were neither crude racists nor simple-minded imperialists; it is hard to imagine them subscribing to stereotypes of the “bad nigger” so prevalent during this period. Even as he lamented the shortcomings of the Amistad group in the pages of the Anti-Slavery Reporter, Lewis Tappan reminded his readers that many calling themselves “Christian” had done far worse. But this did not stop the missionaries from calling out apostasy when they saw it. Cinqué’s real sin, in their eyes, was his ongoing challenge to their authority over the mission. And, in this way, he was not unlike many black activists who became frustrated with white paternalism and decided to pursue a more independent course.

Only a few months before the victorious Amistad captives set sail for Africa, a black correspondent from New Haven, who had probably met Cinqué during the rebel hero’s lengthy imprisonment there, published his thoughts on the subject in the New York newspaper the Colored American (fig. 6). The question of the day was whether black abolitionists should remain subordinate to the white-dominated American Anti-Slavery Society or establish their own separate organization. But the debate spoke to a much larger anxiety. “I am one of those who believe that colored men best know their own wants and grievances, and are best capable of stating them,” he wrote. “Let our white friends, if they wish to help us, give us their countenance and money, and follow, rather than lead us.” I cannot help thinking that Cinqué, if he were here today, might say the same.

If anything, Cinqué’s struggles with his white benefactors only reinforce his hero status. There is no Hans Sprungfeld, no tongueless pirate fiend, lurking behind the most famous of the Amistad rebels. But an excessive focus on this single figure would be a mistake. Framing the Amistad rebellion as a typical American story of individual triumph over oppression obscures the harsh realities that Cinqué and the other survivors faced upon their return. Even after winning their Supreme Court case, the Amistad veterans could not escape the shadow of slavery, and viewed from an African perspective, their story highlights the enduring and insidious reach of the slave trade. At the same time, it draws our attention to the international scope of antislavery activism and the commitment of both white and black abolitionists to open an African front in their revolutionary crusade. Surely this is a form of heroism as well.

Further Reading:

My analysis of the early years of the Mendi Mission is based on a close reading of the correspondence from both white missionaries and native Africans, especially as published in the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Reporter and the Union Missionary between June 1842 and August 1846. Complete runs of both newspapers are extremely rare, so I am grateful to the staff at Cornell University’s Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Yale University’s Sterling Memorial Library, and the American Antiquarian Society for their generous assistance. The American Missionary Association Archives, housed at Tulane University, are the standard resource for all things Amistad, including the missionary efforts in West Africa. This collection is also available on microfilm, but the current index is woefully inaccurate and some of the filmed documents are completely illegible.

The definitive modern work on the Amistad revolt and subsequent trials remains Howard Jones, Mutiny on the Amistad: The Saga of a Slave Revolt and Its Impact on American Abolition, Law, and Diplomacy (New York, 1987). Jones’s landmark article defending Cinqué against allegations of slave trading, along with replies from several preeminent historians, was published in the Journal of American History 87 (December 2000): 923-50. For an excellent analysis of the veneration of Cinqué and the celebrity status of the Amistad rebels within the United States, see Richard J. Powell, “Cinqué: Antislavery Portraiture and Patronage in Jacksonian America,”American Art 11 (Fall 1997): 49-73.

The earliest mention of Cinqué as a slave trader can be found in Fred L. Brownlee, New Day Ascending (Boston, 1946). Although he relies heavily on Brownlee, there is still much worthwhile information on the Mendi Mission in Clifton Herman Johnson, “The American Missionary Association, 1846-1861: A Study of Christian Abolitionism” (Ph.D. diss., University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1958). For a more recent account of the African dimensions of the Amistad saga, see Iyunolu Folayan Osagie, The Amistad Revolt: Memory, Slavery, and the Politics of Identity in the United States and Sierra Leone (Athens, Ga., 2000). Details on the commercial economy of the Sierra Leone region throughout this period can be found in Allen M. Howard, “Nineteenth-Century Coastal Slave Trading and the British Abolition Campaign in Sierra Leone,” Slavery & Abolition 27 (April 2006): 23-49.

This article originally appeared in issue 10.1 (October, 2009).

Joseph Yannielli is a graduate student in the department of history at Yale University. His essay “George Thompson among the Africans: Empathy, Authority, and Insanity in the Age of Abolition” is forthcoming in the Journal of American History.