Commenting on the first of his numerous collaborations with Mark Twain, the illustrator Daniel Carter Beard recalls that his relationship with the author was enabled by an unnamed “Chinese story.” In his autobiography, Hardly a Man is Now Alive: The Autobiography of Dan Beard, he writes:

Mr Fred Hall, Mark Twain’s partner in the publishing business, came to my studio in the old Judge Building and told me that Mark Twain wanted to meet the man who had made the illustrations for a Chinese story in the Cosmopolitan and he wanted that man to illustrate his new book, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. The manuscript was sent to me to read. I read it through three times with great enjoyment.

The Chinese story in question was Wu Chih Tien, a serialized novel purportedly “translated from the original” by the early Chinese American author Wong Chin Foo and the first novel published by a “Chinese American.” (In fact, Wong Chin Foo coined the term “Chinese-American,” and claimed to be the first Chinese person to be naturalized as an American.) Beard’s illustrations for Wu Chih Tien—whose plot features a prince leading a revolt against a usurping empress—may have appealed to Twain on numerous levels: they present historical scenarios from roughly 140 B.C. to 120 B.C.; they depict period costumes, depraved aristocrats, epic journeys, expert horsemanship, and magical events with versatility and grace; and they elegantly supplement a plot that pits a national populace against a brutal and corrupt regime. Twain’s interest in Wu Chih Tien did not stop at Beard’s illustrations: a passage from his notebooks disparaging a travelogue published in the February 1889 issue of Cosmopolitan reads: “Pity to put that flatulence between the same leaves with that charming Chinese story.” More broadly, Wu Chih Tien addressed an interest in China, Chinese immigrants, and transpacific sites of U.S. imperialism that spanned Twain’s career. In 1868, Twain published an article praising the Burlingame Treaty for supporting China’s self-determination and equal status with Western nations, as well as the rights of Chinese laborers in the United States. Over the following decades, Twain continued to write—without always publishing—sporadic essays exhibiting strong sympathies with the Chinese in the United States, ranging from Roughin’ It and the unfinished “Goldsmith’s Friend Abroad Again” to “Disgraceful Persecution of a Boy” and the posthumously published “Fable of the Yellow Terror.”

Given Twain’s interests in the “charming Chinese story,” its illustrator, and the broader topic of Western incursions in China, it seems likely that he continued to peruse chapters from the novel as they appeared in subsequent months. While Twain was editing and revising A Connecticut Yankee, he may have read the May 1889 installment of Wu Chih Tien, which describes a battle strategem that incorporates both the technology of gunpowder and the military tactics of Sun Tzu’s Art of War. “In the pass, through which ran the main road to the camp, [General Mah] ordered deep pits to be dug, and these were filled with powder that was to be exploded by fuses if the foe succeeded in entering the defile.” A few pages later, the explosion kills thousands of the corrupt empress’s soldiers:

At length they gained the pass, and poured in till the foremost men could see the white tent of the prince, with his banner above it.

Then they cheered till the echoes trembled; and, as if this had been the signal, the rocks from the tops of the pass came thundering down, and the powder-pits at the bottom were fired, and twenty thousand men were hurled into the sky.

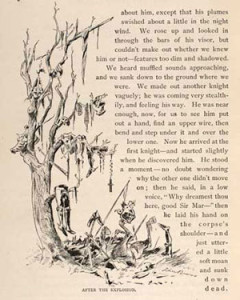

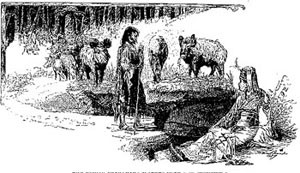

The toppled rocks and explosion lead to a momentary victory, as enemy soldiers retreat from a pass suddenly filled with “blood and the limbs of torn men.” Whether he read this passage or not, Twain probably noticed Beard’s rendering of this scene in one of Wu Chih Tien‘s largest and most striking illustrations (fig. 1). It is easy to imagine that this image secured Beard’s position as Twain’s illustrator of choice: Beard was offered the contract for illustrating A Connecticut Yankee in June, just a few weeks after this image appeared.

This scene from Wu Chih Tien bears a striking resemblance to the descriptions of exploded buildings and bodies that recur throughout A Connecticut Yankee (figs. 2 and 3). In that novel’s climactic scene—a massacre euphemistically named the “Battle of the Sand Belt”—the Connecticut Yankee and his followers instantaneously slaughter tens of thousands of knights by detonating “dynamite torpedoes” buried beneath a sand belt. “Great Scott! Why, the whole front of that host shot into the sky with a thunder-crash, and became a whirling tempest of rags and fragments; and along the ground lay a thick wall of smoke that hid what was left of the multitude from our sight.”

Connecticut Yankee and Wu Chih Tien share more than a fascination with the brutally effective use of explosives. Both novels project modern ideas and technologies into the past to counteract conventional opinions about the progressive nature of history and the socially backward status of non-Western civilizations. By doing so, Twain and Wong countered the nativist visions of white masculinity characteristic of popular romance novels featuring historical or foreign settings. Reading these novels together helps us better understand how contending visions of empire, “progress,” and racial inequality were presented and debated in works of literary fiction. It also makes visible affinities between the two writers and their audiences that—in spite of Twain’s career-long interest in the Chinese—neither author noted in print. As platform lecturers, humorists, newspaper editors, and occasional political activists, both Twain and Wong understood how entertaining adventure novels could sway public sentiment and politics.

Both A Connecticut Yankee and Wu Chih Tien seem out of place when compared with popular romances published in the 1880s and 1890s. Romantic adventure novels responded to the closing of the U.S. frontier and the rise of industrial capitalism by projecting ideals of force, passion, and physicality onto medieval and foreign cultures such as Richard Harding Davis’s Soldiers of Fortune (1897), Charles Major’s When Knighthood Was in Flower (1898) and F. Marion Crawford’s Via Crucis (1899). In these romances, masculine American heroes could rescue themselves from becoming urbane, sophisticated, and over-civilized by heroically rescuing kingdoms and romancing exoticized women in historical and/or foreign settings. While the rage for historical romances was fueled by the rise of cheaper periodicals in the 1890s, the groundwork for the genre’s success was laid in the 1880s. That decade saw the publication of Lew Wallace’s vastly popular historical novel Ben-Hur (1880); the revival of interest in Sir Walter Scott by critics who saw in his corpus (as historian T.J. Jackson Lears puts it) “the emblem of a larger, fuller life”; and widespread anxieties about industrialism’s enervating influences upon Anglo-Saxon men.

Hank Morgan, the Yankee protagonist and narrator of A Connecticut Yankee, provides a satirical counterpoint to the romantic heroes of Sir Thomas Malory, Sir Walter Scott, Alfred Lord Tennyson, H. Rider Haggard, Lew Wallace, and other authors popular in the 1880s. Twain’s novel derives much of its humor from the distance between Hank’s utilitarian perspective and the chivalric ideals that his contemporaries often associated with medieval society. Mysteriously transported to the sixth century, Hank quickly rises to power as King Arthur’s chief advisor by passing off scientific feats and nineteenth-century technologies as “magic.” In an allegory of imperialist development, Hank introduces modern technologies of transportation, communication, education, hygiene, governance, and war to medieval England. However, these reforms precipitate increasingly strident forms of antimodern resistance, to which Hank responds with increasingly violent measures that culminate in the novel’s explosive finale. The contradictory nature of Hank’s design is eloquently expressed by his mixed metaphors of enlightenment: he figures modernity as both a benign mechanical lever ready to “flood the midnight world with light at any moment” and a “serene volcano…giving no sign of the rising hell in its bowels.” Twain thus satirizes both romantic accounts of the past and imperialists’ arrogant, often violent schemes for “modernizing” colonized lands and populations. According to Lears, Twain’s novel expresses a deep ambivalence about the culture of “antimodern vitalism” which associated physical vitality with the heroic past: “It is possible to imagine the Yankee as Twain himself, tossing on his bunk, torn between loyalty to the respectable morality of the bourgeoisie and longings for the lawless realm of childhood.”

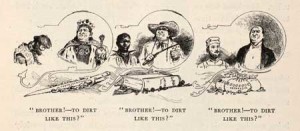

A Connecticut Yankee‘s satire is directed at multiple targets. First, it undermines the romanticization of the past by juxtaposing medieval romances like Malory’s Morte d’Arthur with historical analysis gleaned from works such as William Lecky’s History of European Morals from Augustus to Charlemagne (1869) and History of England in the Eighteenth Century (1878-1890). If historical romances fantasized that swashbuckling performances could be reenacted in foreign battlefields of the present, Twain exposes how chivalric ideals masked the oppressive regimes of the Catholic Church and feudal state. Calling in question the very notion of historical progress, A Connecticut Yankee also highlights resonances across historical periods by associating medieval peasants with antebellum American slaves, poor whites, and industrial laborers (fig. 4). Twain also links a peasant mob to “a time thirteen centuries away, when the ‘poor whites’ of our South who were always despised and frequently insulted, by the slave-lords around them, and who owed their base condition simply to the presence of slavery in their midst, were yet pusillanimously ready to side with slave-lords in all political moves for the upholding and perpetuating of slavery…” (fig. 5)

Although A Connecticut Yankee‘s references to imperialism are more circuitous, they are also more ubiquitous and compelling than its references to antebellum slavery and Gilded Age capitalism. The novel invokes relations of imperialism by alluding to Gatling guns and Christopher Columbus’s use of a lunar eclipse to control “savage” populations. More importantly, the ideology of imperialism informs Hank’s entire project of enlightening the sixth century through technological, political, and behavioral transformations. Imagining that his avowed goal of progress justifies blowing up buildings, posing as a magician, establishing a secret school or “man-factory” for indoctrinating young men, and slaughtering recalcitrant knights, Hank embodies both an outlook and a set of strategies characteristic of imperial regimes. Critics including Kaplan, Steven Sumida, and John Carlos Rowe have associated Hank’s violent and surreptitious methods of disciplining medieval subjects with historical phenomena such as the British empire, U.S. policies of Indian Removal and assimilation, and various Western incursions on Hawai’ian sovereignty which culminated in its annexation by the United States in 1898. Sumida, for example, points out that just prior to writing A Connecticut Yankee Twain had attempted an unfinished novel about how Christian missionaries affected the lives of Hawai’ians. Rowe links the novel to China by suggesting that Hank’s duel with five hundred knights echoes the celebrated death of the British colonial officer “Chinese” Gordon. Although he died while fighting Madhists in Khartoum, “The legend of Chinese Gordon as imperialist hero begins with his appointment in 1863 as military commander of the forces organized by the United States and Great Britain to quell the Taiping Rebellion…and to prop up the tottering Manchu dynasty in China.”

A Connecticut Yankee famously concludes with Hank reluctantly enacting his own version of a colonial massacre, only to be trapped by the heaps of decaying corpses he has created and, finally, put into an indefinite sleep by Merlin. Hank’s project backfires on both a practical and a moral level: not only does England’s peasantry prove too recalcitrant to turn against the Church and aristocracy, but the failings of sixth-century feudalism are repeated in the failures of nineteenth-century capitalism. Twain’s novel exposes the violence and hypocrisy underlying ideals of physical force, chivalric masculinity, and historical progress—ideals that were becoming central features of popular historical romances as well as the antimodern writings of people like Frank Norris, Theodore Roosevelt, and Brooks Adams.

Like Twain, Wong Chin Foo made a name for himself by creating and manipulating controversy in the periodical press (fig. 6). Wong’s prolific publications—mostly in the form of nonfiction essays and sketches—appeared in many of the same periodicals that Twain published in around the turn of the century, including Cosmopolitan, The Independent, Youth’s Companion, Harper’s, North American Review, The Atlantic, and The Chautauquan. Throughout his public career, Wong’s careful self-fashioning as an exiled Chinese nationalist makes it difficult to distinguish between his public persona and biographical facts. In 1873, he told the New York Times that he had been sponsored by “an American lady philanthropist” to attend “a Pennsylvania college” where he graduated with honors and observed American “social and political clubs, benevolent societies, trade unions, &c.” before returning to China. The biography of Wong that appeared in the monthly Shaker Manifesto (1879) is typical:

Though only 26, he has visited this country twice, has been an officer of the imperial government at Shanghai, and a rebel against the present Tartar emperor. For this last a price was set on his head, and he was hunted for months, never getting into such serious danger as when he put himself into the hands of English missionaries, who, finding out who he was, decided to give him up to the emperor. He remonstrated against their betrayal of him to torture and final execution by cutting him into 18 pieces; but they promised to obtain him the favor of simply having his head cut off, and thereupon locked him in a room, and told him to put his trust in Jesus. Disregarding this very practical advice, he broke out and got to the coast, where an irreligious seaman gave him passage to Japan. Thence he came to San Francisco on a steamer which carried in the steerage 200 Chinese young women of the lower class, imported for infamous purposes; and on arriving he went into the courts and secured their freedom and return to their country.

The nineteenth century marked a turbulent period of China’s history, when missionaries and foreign settlements were encroaching on the cultural and political hegemony of the Qing Dynasty’s Tartar rulers. Wong put that turbulence to good use in creating a picture of himself for U.S. readers. He indicts Western missionaries in order to fashion himself as an exiled hero: a nationalist rebel with “a price…on his head” who manages to appeal to U.S. laws to liberate 200 Chinese slave women “on arriving.” The U.S. consul at Yokohama who helped him escape describes Wong’s exile in terms that could apply to Hank Morgan’s reform projects in A Connecticut Yankee: “not approving of the Oriental methods of government, [he] had attempted to establish—over night—a republican form of administration in that conservative empire.” In the United States, Wong attempted to sway public opinion against the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (which would be considered for renewal in 1892) by mobilizing cosmopolitan, parodic, satirical, and protest discourses in a variety of periodicals and newspapers. These strategies range from a comic dialect poem (“Moon faced gal on balcony floor/ See young fellow down by door…”) to publicly challenging anti-Chinese demagogue Denis Kearney to a duel, from touring as a “Buddhist missionary” lecturer to founding the first Chinese newspaper in the United States, The Chinese-American. Wong’s literary production and public performances consistently present the Chinese as subjects who are not only assimilable to U.S. norms, but who already possess qualities that Americans would identify with, such as sentimental tendencies, a passion for justice, and a strong sense of humor.

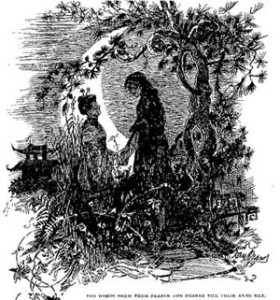

Although Wu Chih Tien, the Celestial Empress: A Chinese Historical Novel purports to be a “translation” of a Chinese narrative, I have not been able to identify a plausible source text. In the early 1880s, several literary periodicals announced that “Wong Ching Foo” was going to translate “The Fan Yong: or the Royal Slave,” a Chinese historical novel written by “Kong Ming” “twenty-two hundred years ago.” But Kong Ming was the name of a character in the classic Chinese novel Water Margin; “the Royal Slave” echoes the subtitle of Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko; and the earliest Chinese novels were written in the fourteenth century. All of this suggests that Wong was the author. Whether he wrote or translated Wu Chih Tien, Wong is responsible for both its language and commentary on Gilded Age assumptions about history, race, and masculinity. Loosely based on the controversial regime of the Empress Wu Zetian from A.D. 655-705, the novel begins with the concubine Wu Chih Tien usurping the throne, forcing the emperor’s newborn son into exile, and subjecting the populace to brutal taxes intended to fund her extravagant lifestyle. The plot’s focus then shifts from the empress to the prince, Li Tan, who grows into a tall, beautiful, talented, eloquent, and sympathetic young man. Hounded by the empress’s soldiers, Li Tan exchanges clothing with a swineherd to escape (fig. 7). He is then pursued by Tartars intending to sell him into slavery, but he escapes slavery—at least nominally—by indenturing himself to the cruel merchant Wu Deah. Just as the adoption of a swineherd’s clothes and the threat of being duplicitously sold into slavery echo recurring motifs in Twain’s novels, Wu Deah’s offer to Li Tan resonates with Twain’s interest in the blurry boundaries between “free,” forced, and indentured labor: “If you will pledge yourself to work for me for five years, I will give you fine raiment, plenty of food, and a nice bed where my slaves sleep; and when your time is up I will give you a new suit of clothes and five taels; and then you will be a very rich man—for a swineherd.” Immediately after Li Tan saves himself from slavery by accepting this offer, Wu Deah has him brutally whipped for failing to kow-tow properly.

At Wu Deah’s palace, Li Tan begins a romantic relationship with Sho Kai, Wu Deah’s poor niece. After the two pledge their love and the prince entrusts his fiancée with the imperial seal, Li Tan leaves to rejoin the rebel army. Sho Kai is tricked into believing Li Tan has died, and marries an arranged suitor in despair; Li Tan nearly enters into an arranged marriage, too, when he learns of Sho Kai’s apparent infidelity. Once these romantic complications are resolved, Li Tan and Sho Kai are finally married and the novel comes to a swift conclusion: the final battle for China’s capital is narrated in two short pages. The novel’s conclusion shifts from scenarios of punishment (including a graphic illustration of the empress’s half-naked body ablaze) to reports of the new emperor’s happy and fruitful marriage. Li Tan’s love match with Sho Kai signals a shift away from polygamy and arranged marriage towards a model of freely contracted marriage across class lines (fig. 8). In a period when U.S. law presumed that Chinese women seeking to enter the country were prostitutes, and when missionaries and other writers focused disproportionate attention on misogynistic Chinese practices such as footbinding, prostitution, polygamy, and infanticide, Wong’s novel builds towards an exemplary monogamous marriage: “And although [the emperor] might have had many wives besides Sho Kai, he was too happy to want another.” The arc of the novel thus moves from the polygamous situation from which Wu Chih Tien rose to power to one of the fundamental building blocks of Western liberal society: a monogamous, self-contracted, and prolific marriage.

Drawing on the conventions of historical romance, Wu Chih Tien thus represents heroic and liberally minded Chinese men in an era characterized by Chinese Exclusion and racist stereotypes ranging from the “Heathen Chinee” and “yellow peril” to Twain’s own effeminizing formulation (in Roughin’ It) of “The Gentle, Inoffensive Chinese.” By taking as its protagonist the handsome, robust, intelligent, sympathetic prince, Wu Chih Tien both appropriates and unravels the equation of whiteness with imperial manhood that would underwrite many historical novels of the 1890s. Ironically, the generic conventions of historical romances that make Li Tan’s triumph possible trap the novel’s female characters. The genre’s sexist logic contrasts the idealized male hero with both the passive Sho Kai—who is ultimately rescued—and the demonized usurping empress—who is ultimately burned alive.

As “a Chinese rebel chief…now an exile for the part he took in the rebellion to overthrow the present Tartar dynasty,” Wong would have had strong reasons for identifying with the exiled, liberal-minded prince. Likewise, Wong’s choice of subject suggests parallels between the usurping empress and the contemporary regime of the Manchu Empress Dowager Cixi in China. Cixi’s conservatism and political scheming came to a head in her power struggle against the reformist Prince Gong, who she felt had become too favorable to foreigners; in 1884, Cixi consolidated her power by forcing the prince to retire to private life. Exiled for promoting pro-Han and modernizing reforms in China, Wong framed his story of the revolutionary removal of Wu Chih Tien as an allegory—and an argument—for the overthrow of the Qing (Manchu or Tartar) dynasty in China (an overthrow that eventually occurred in the 1911 Xinhai Revolution). As Western nations were competing for commercial, religious, and political influence in China, Wong’s novel endorsed self-rule and reforms designed to strengthen the nation against foreign encroachments, as well as to protect the rights of Chinese living abroad. Generating support for a political revolution in China, of course, counteracts racist thinking by suggesting that the Chinese are capable of self-rule-even if that self-rule must be allegorized through the installation of a rightful, popularly supported emperor. Unlike most later popular romances that were set in foreign countries, national liberation in Wu Chih Tien does not call for the intervention of a heroic American man. By imagining Li Tan as an enlightened despot capable of ruling China objectively and responsibly, Wong reaffirms an earlier Harper’s article on “Political Honors in China” (1883), in which he argued that China’s system of rule is grounded in democratic systems of meritocracy and substantive (as well as merely formal) justice. Alluding to the Fifteenth Amendment, “Political Honors” argues that China’s system of assigning government positions based on competitive examinations differs from U.S. politics insofar as the former makes “no distinctions…relative to nationality, color, or previous condition to servitude.”

Wu Chih Tien suggests that China can adopt modern technologies of war and governance without the help of colonial rulers—indeed, the novel argues that China had already been ruled by an enlightened, monogamous, and liberal emperor over a century before the birth of Christ. As Wong put it in his controversial essay “Why Am I A Heathen?”, “we [Chinese] decline to admit all the advantages of your boasted civilization; or that the white race is the only civilized one. Its civilization is borrowed, adapted, and shaped from our older form.” Wu Chih Tien‘s depictions of the buried gunpowder strategem and an egalitarian emperor—which appeared months before Twain published on similar topics in his masterpiece of anachronism—surpass even Yankee in unsettling Eurocentric notions of technological and political progress. Through its strategic use of anachronism, the novel implicitly argues that, far from being “unassimilable” (as anti-Chinese agitators had long believed and as numerous Chinese exclusion acts presumed) to Western liberal practices, the Chinese had in fact invented many of those practices. Indeed, Wong’s argument about China’s prior invention of civilized practices suggests that Wu Chih Tien is not anachronistic at all: rather, it is anti-anachronistic. The novel emphasizes modern aspects of seventh-century China in order to unravel the representation of China as—to borrow Anne McClintock’s term—”anachronistic space,” or an atavistic space remote from historical “progress.” Reading Wu Chih Tien with A Connecticut Yankee provides a concrete reference point for the anti-imperialist allegory of Twain’s novel and shows that Twain was not alone in strategically deploying literary anachronism to combat the imperialist tendency to represent real and potential colonies as “anachronistic.” While A Connecticut Yankee has already been linked to multiple imperialist contexts ranging from the trans-Mississippi frontier and Hawai’i to Africa and India, Wong’s “Chinese Historical Novel” introduces a nonwestern, non-white nation that, in the second century B.C., was (by Hank Morgan’s standards) already more politically and technologically “advanced” than sixth-century England. Explosives, gunpowder, and meritocracy were not exclusively Western inventions: ironically, they could have been transported into sixth-century England from sixth-century China, rather than from the 1880s.

Further reading:

For a sampling of Wong Chin Foo’s literary production, see Wong Chin Foo, “The Story of San Tszon.” Atlantic Monthly 56:334 (August 1885): 256-63; Wong Chin Foo, “Why Am I A Heathen?” The North American Review 145:369 (August 1887): 169-79; Wong Chin Foo, “The Chinese in New York,” Cosmopolitan 5 (March-October 1888): 297-311. Studies of Wong’s writings and political activism include Qingsong Zhang, “The Origins of the Chinese Americanization Movement: Wong Chin Foo and the Chinese Equal Rights League,” in Claiming America: Constructing Chinese American Identities During the Exclusion Era, eds. K. Scott Wong and Sucheng Chan (Philadelphia, 1998); Carrie Tirado Bramen, The Uses of Variety: Modern Americanism and the Quest for National Distinctiveness (Cambridge Mass., 2000); John Kuo Wei Tchen, New York Before Chinatown: Orientalism and the Shaping of American Culture, 1776-1882 (Baltimore, 2001); and Hsuan L. Hsu, “Wong Chin Foo’s Periodical Writing and Chinese Exclusion,” Genre: Forms of Discourse and Culture 39:3-4 (Fall/Winter 2006): 83-105.

For a sampling of Twain’s writings on imperialism and anti-Chinese racism, see Mark Twain, “The Treaty with China,” New York Tribune (Aug. 4, 1868), reprinted inThe Journal of Transnational American Studies 2:1 (2010); Mark Twain, “Disgraceful Persecution of a Boy,”Galaxy (May 1870): 717-18; Mark Twain, “Goldsmith’s Friend Abroad Again,” in Collected Tales, Sketches, Speeches, & Essays 1852-1890, ed. Louis J. Budd (New York, 1992): 455-70; Mark Twain and Bret Harte, Ah Sin: A Dramatic Work (San Francisco, 1961); Mark Twain “To the Person Sitting in Darkness,” North American Review 182:531 (Feb. 1901): 161-76; Mark Twain, “The War Prayer,” in Great Short Works of Mark Twain, ed. Justin Kaplan (New York, 2004): 218-21; and Mark Twain, “The Fable of the Yellow Terror,” in The Devil’s Race-Track: Mark Twain’s “Great Dark” Writings, ed. John Sutton Tuckey (Berkeley, 2005): 369-72.

For studies of Twain’s engagements with imperialism, see Fred W. Lorch, “Hawaiian Feudalism and Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court,” American Literature 30:1 (Mar. 1958): 50-66; Stephen H. Sumida, “Reevaluating Mark Twain’s Novel of Hawaii,” American Literature 61:4 (Dec. 1989): 586-609; John Carlos Rowe, “Mark Twain’s Rediscovery of American in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court,” in Literary Culture and U.S. Imperialism: from the Revolution to World War II (Oxford, 2000): 121-40; Amy Kaplan, “The Imperial Routes of Mark Twain,” in The Anarchy of Empire in the Making of U.S. Culture (Cambridge, Mass., 2002); Joel A. Johnson, “A Connecticut Yankee in Saddam’s Court: Mark Twain on Benevolent Imperialism,” Perspectives on Politics 5:1 (2007): 49-61. On Twain’s career-long interest in China and the Chinese, see Martin Zehr, “Mark Twain, ‘The Treaty with China,’ and the Chinese Connection,” Journal of Transnational American Studies 2:1 (2010) online publication. On illustrations in Mark Twain’s writings, see Daniel Carter Beard, Hardly a Man is Now Alive: The Autobiography of Dan Beard (New York, 1939), and Henry B. Wonham, “‘I Want a Real Coon’: Mark Twain and Late-Nineteenth-Century Ethnic Caricature,” American Literature 72:1 (March 2000): 117-52.

On the historical romance, see William Dean Howells, “The New Historical Romance,” North American Review 171 (1900): 935-48; George Dekker, The American Historical Romance (Cambridge, 1990); Amy Kaplan, “Romancing the Empire,” in The Anarchy of Empire ; T. J. Jackson Lears, No Place of Grace: Antimodernism and the Transformation of American Culture (Chicago, 1994); and Andrew Hebard, “Romantic Sovereignty: Popular Romances and the American Imperial State,” American Quarterly 57:3 (September 2005): 805-30.

Thanks to Edlie Wong, Martha Lincoln, Cara Shipe, Kristian Jensen, Catherine Kelly and a Mark Twain Circle panel at the American Literature Association for responding to earlier versions of this essay.

This article originally appeared in issue 11.1 (October, 2010).