One hundred and seventy-five bunches of asparagus. Sixty-five bunches of radishes. Three varieties of beans. Eleven hundred heads of cabbage. Twenty-four thousand three hundred and seventy-five quarts of milk. Thirty bushels of apples. Three varieties of pears, most plentiful were the Seckel–two hundred bushels. Currants, gooseberries, strawberries, grapes. Altogether the Twenty-Fifth Annual Report of the Trustees of the New York Asylum for Idiots lists forty-one kinds of produce, their yields, and price. The year is 1875. If you were studying landscape history in upstate New York, you could use these reports to track the yield data across the last quarter of the nineteenth century. But you could also learn about the history of science, international communications, industrialization, education, disability, and the professionalization of social work. In the Superintendent’s Reports, 1851-78, you would come to know the institution’s director, Hervey Wilbur. I like the man and feel assured, after reading nearly thirty years of his remarks, that his interests squarely focused on the wellbeing of his charges. They were mostly young people, ages six to eighteen, New Yorkers who fell into the category widely known as “teachable idiots.” Today, we would describe these children by their diagnoses-names like Down, Asperger, Williams, or Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, or the general label, autistic. Some of Wilbur’s charges probably acquired their cognitive impairments from malnutrition, high fever, or accidents. But regardless of cause, he understood their humanity and had faith in their possibilities. And perhaps most important, he acknowledged the limits of his and other scientists’ knowledge about the brain’s relationship to the body: “Various methods of classification in the case of idiots have been suggested,” Wilbur reported in 1875, “but these are either arbitrary or based upon pathological distinctions that are valueless, for any practical purposes of classification.” He had been in the field for twenty-five years. He continued, “[A]s to the results of management and treatment or training and instruction, or as it is put the prognosis, I see no guide in such a system of classification for determining this.” The nomenclature has changed, but special education teachers and neuropsychologists today would agree: a diagnostic label is not a prognosis. The categorizing classification term–a medical diagnosis–does not predict or describe the child with a cognitive impairment’s possibilities for competence and achievement. It is one of the most difficult truths about cognitive disability to grasp and accommodate fairly nowadays. Wilbur was advocating the point within the terms of his own day, but even then the classification systems were constantly shifting. Think about the name changes of the New York State Asylum for Idiots, founded 1851. Why does it become, in 1891, the Syracuse State Institution for Feeble-Minded Children; in 1921 the Syracuse State School for Mental Defectives; in 1927 the Syracuse State School? Did the shift in nomenclature reflect an improvement in our understanding of the conditions? the services? the outcomes? In 1973, the onetime “asylum” became the Syracuse Developmental Center, then closed permanently in 1998. Like asylums for the mentally ill, the state-run schools for children and adults with cognitive disabilities found across the United States from the 1850s until the 1990s were usually self-contained communities as isolated from society’s mainstream as prisons are today. The New York State Asylum opened in 1851 with about thirty students; the population doubled by 1853. There were 250 by 1878, 850 in 1922. But even as the crowding worsened and living conditions deteriorated, residents and staff must have found moments of refuge, sources of resilience.

I like to think this was possible at the Syracuse New York State Asylum during, say, a few days in September 1880. At work in the kitchen, the women would be swept up in aromatic clouds of cooking pears, applesauce, jellies. Residents and staff working side by side, filling glass mason jars with fruit, listening to the jars jiggle as they boil in vats. I want to believe that in November the entire community, residents and staff, knew the pleasure of eating homegrown pears canned in sweet heavy syrup. That’s when they are best, their texture still firm, the taste of summer still evident. I first tasted home-canned pears as a child in the 1950s. I grew up in a world in which the majority of young people with cognitive disabilities, rich or poor, still lived lives segregated from the community. This ‘other segregation’ is mostly over now. By federal law passed in the 1970s, children with disabilities are integrated in their communities’ public schools. I am an artist, not a historian, but my work is about the historical legacy that people with disabilities encounter. As an artist making documentaries in film and radio, I use history–its methods and records–to seek out the etymologies of habits of thought that persist in the here and now. I need this conversation with the past: Disability history invigorates my vocabulary, my imagination, it satisfies a deep personal need to know, even when what I learn is harrowing or sorrowful. My need to engage in this conversation with disability history arose because I have an on-going dialogue with my children about their encounters with it. At some point, your children may encounter this need too, as disability is the one category of identity any of us can join at any time. To help bridge this generation gap, and to accelerate the opportunities for young people to explore the historical experience of disability and identity as a disabled person in society, I founded a museum. It’s virtual, no bricks or mortar. But it’s a real museum with programs; there’s a library, a museum with exhibits, and an education area. The library is a searchable digital archive of primary sources (text documents, visual stills, and in the future, an audio collection: oral histories, radio programs and advertising, 78-rpm lectures) related to disability history. The museum sector will contain interpretive exhibits that draw library artifacts together and explore themes and topics in disability history. The education sector will provide curriculum materials linked to library artifacts and museum exhibits. Only the library is open now, but the wings will unfold in the foreseeable future. The library ‘borrows’ its materials from public and private collections around the country. It contains digital surrogates of materials about different groups of people with disabilities. The collections are searchable, and because our audience ranges from sixth graders to scholars, the finding aids are quite flexible–there are tools for keywords, dates and date range, sorting, formats, sources, and–for those users who want a quick sense of what’s there, we’ve created general subject directories. We aim to represent the range of disability history resources by selecting representative artifacts from the genres where disability history is found: veterans’ pension documents, the circus sideshow, moral literature, postcards of institutions, deaf- and polio- and blind-community newspapers and newsletters, service-club ephemera and meeting minutes. We love to find and post items that are truly unique. And we include, from 1775-1990, personal accounts and objects created by people with disabilities about their own experiences. We add to our collection at the rate of about one hundred artifacts every four to six weeks. We cannot be comprehensive; historical evidence relevant to the experience of people with disabilities, once you start looking for it, is simply everywhere. People with disabilities, after all, have always been here. The one area where we will not concentrate efforts, unless there is a need to use the materials in a museum exhibit, is traditional medical history–the tools of the trade, the landmark discoveries and experiments. This material is abundantly recorded and available in other collections. The Disability History Museum is interdisciplinary in approach, but the shared experiences of people, not their diseases, are what is most essential to our collecting mission. So, for example, a different sense of the world of Hervey Wilbur and his charges and the staff at the Syracuse Asylum can be discovered in nineteenth-century Sunday-school stories about children with disabilities.

Pull up Jessy Allan, a little novelette, first published in 1824. It’s about a girl who must make a commitment to God, but then needs to have a leg amputated, without the aid of anesthesia. Will her commitment see her through? In this tale, religious faith provides palpable comfort. But these stories contain much more than moral visions and proscriptions. Poor Matt; Or, The Clouded Intellect is an 1869 tale about a ‘visitor’ and a cognitively disabled boy seemingly based on fact. Matt’s affliction, and his care, are understood in theological terms. But beyond the theological underpinning you also see the visitor and the local community around Matt practicing what we today call early childhood intervention techniques–speech, occupational, and physical therapy. And he improves; he is educable and in the community. Then there are those tales like Patience and Her Friend, where Patience’s crisis involves submitting to God’s will and its social corollary–never complaining or expressing anger. It’s a restriction that in her case, Patience, a hunchback girl with a beautiful friend, seems particularly cruel. In Crazy Ann, the theological requirement is mercy: compassion is abundant in this story, and mental illness is ascribed to natural, not divine, causes.

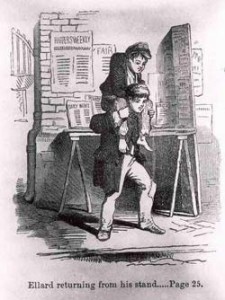

John Ellard: The Newsboy, 1860, is one of my favorites in this genre. It’s a memoir by one of the founders of the Philadelphia Newsboys’ Home, Frederick Starr. He introduces us to a real boy with abundant character. Though there is the obligatory deathbed salvation scene and accounts of religious services, the intent of the book seems to be to prove that this group of smoking and drinking, urban street urchins is salvageable. This is a well-observed portrait of a proud, independent, adventurous disabled child and his buddies. Starr tells us what he knows about Ellard and friends, where they were born, how they work, their habits and interests, and the role of the Home in their lives. Cleanliness, godliness, drink and risk, they are all in this book, but it is not a fiction, so gentle sentiments are important to it. This is a midcentury account of urban street kids with visible and invisible disabilities. They are orphans, runaways from poverty, abuse or neglect, the children of alcoholics: today you find them on the streets in Rio, Los Angeles, Moscow, Lagos, Islamabad, Chicago. For something related but different in the realm of religious experience, try Thomas Gallaudet’s Sermon, On the Duties and Advantages of Affording Instruction to the Deaf and Dumb, 1824. It’s an inspirational talk, printed and sold as a tract by Isaac Hill. According to a preliminary note the speech was not designed “to solicit pecuniary contributions, but to excite in the public mind a deeper interest than has hitherto been felt for the DEAF AND DUMB.” Fundraising actually was a goal, but contemporary readers will find ‘the ask’ awesome. First, Gallaudet poses a question: Who are the heathen of our day? After listing the unconverted across the continents, he directs his listeners to the nonbelievers here at home, and then he cites another category:

Yes, my brethren, and I present them to the eye of your pity, an interesting, an affecting group of your fellow men;–of those who are bone of your bone and flesh of your flesh; who live encircled with all that can render life desirable; in the midst of society, of knowledge, of the arts, of the sciences, of a free and happy government, of a widely-preached gospel; and yet who know nothing of all these blessings; who regard them with amazement and a trembling concern; who are lost in one perpetual gaze of wonder at the thousand mysteries which surround them; who consider many of our most simple customs as perplexing enigmas, who often make the most absurd conjectures respecting the weighty transactions of civil society, or the august and solemn rites and ceremonies of religion; who propose a thousand enquiries which cannot be answered, and pant for a deliverance which has not yet been afforded them. These are some of the heathen;–long-neglected heathen;–the poor Deaf and Dumb, whose sad necessities have been forgotten, while scarce a corner of the world has not been searched to find those who are yet ignorant of Jesus Christ.

In Gallaudet’s vision we are potentially all God’s children, but only when we know the Protestant Word. Sign language is the means to bring these heathen out of darkness. Gallaudet directed the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, a school he cofounded with Laurent Clerc and Mason Cogswell. He is writing this sermon nearly a decade after studying sign language with Clerc, a French deaf man and teacher. Clerc describes how he learned to communicate–in English–in his Diary of their voyage to America in 1816.

The diary is about a deaf man’s life, a life richly textured, adventure filled. Like many of the artifacts in the Disability History Museum, it makes us ask, what is a disability story? In following the Syracuse Asylum trainees back into the community (and many did return), we need to ask: When does an impairment become a limitation in someone’s existence? When reading Isaac Hunt’s Astounding Disclosures! Three Years In A Mad House, his account of time spent at the Maine Insane Hospital, we need to ask: When does a legal definition of disability, in this case insanity, become more important than a individual’s sense of his or her own authority? What happens when we shift from a moral assessment of a disabling experience to a medical one? What happens when we shift from considering the circumstance of a specific individual with a tragic story about impairment, to considering groups of individuals with similar impairments as minority populations with basic human and civil rights? Disability issues are deeply complex and vexed topics in our culture. This is not new. But today we live in world where a map of the human genome helps predict what kinds of disabilities all of us are potentially vulnerable to acquiring in our life span or passing along to another generation. The historical study of the experience of people with disabilities points toward a historical understanding of the body and its differences: the human species and how we have conceptualized and understood the variations within it. Hervey Wilbur would be glad for the contemporary technologies that let us see inside the structures of the brain and our genes, but I think he would still be skeptical and cautionary about our willingness to confuse categories of classification with prognoses.

This article originally appeared in issue 2.3 (April, 2002).

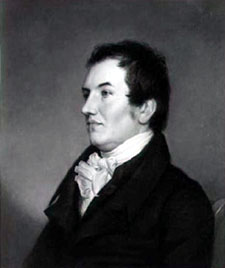

Laurie Block founded DisabilityMuseum.org, a virtual museum, in her role as executive director of Straight Ahead Pictures, Inc., a small nonprofit company whose mission is to create innovative media projects and educational forums that use archival materials and oral history to foster community dialogue about contemporary social issues. Block coproduced, narrated, and wrote Beyond Affliction: The Disability History Project, a four-hour radio series broadcast on NPR, and winner of the Robert Kennedy Journalism Award, 1999. She also produced and directed the award winning feature documentary FIT: Episodes in the History of the Body, broadcast on PBS in 1994.