An antebellum museum in cyberspace

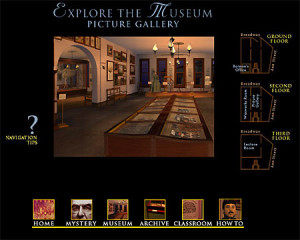

On July 13, 1865, one of the most celebrated institutions in the United States, the American Museum, burned to the ground. But thanks to the wonders of technology, it has been rebuilt—sort of—on a Website called The Lost Museum, sponsored by the American Social History Project of the CUNY Graduate Center, in collaboration with the Center for History and New Media at George Mason University. As it was managed by Phineas T. Barnum, the original American Museum was located in lower Manhattan and presented an ever-growing collection of wonders across five floors, ranging from “cosmoramas” and wax figures, to aquariums and live-animal specimens, to “moral representations” in the Lecture Room.

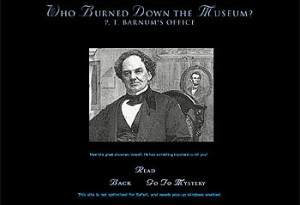

This new virtual version uses the resources of the Web to present artifacts relating to Barnum’s establishment and to recreate historically particular spaces of an antebellum dime museum. Here, we have a central room linked to three “floors,” containing “Barnum’s Office,” which houses, among other items, a desk adorned with a photograph of Barnum with Tom Thumb, an 1850 Illustrated Guide Book to the Museum, an 1844 image of Bowery B’hoys, and a handwritten letter expressing concern over cruelty to animals. The second floor contains a portrait gallery, while “The Lecture Room” on the third floor contains a screen, framed by a theatrical proscenium, on which the viewer can see magic-lantern slide shows about great fires or nineteenth-century etiquette. Perhaps in deference to the shorter attention span of today’s technology-saturated museum goers, the designers have made a selective version of Barnum’s museum. If antebellum visitors made an entire day of their trips to the real thing, you can be in and out of “The Lost Museum” in about half an hour.

Despite the verisimilitude with which it is portrayed, “The Lost Museum” does not exist in the physical world; it is, rather, an ingenious visual hoax. A virtual museum of oddities and artifacts, it offers a wide-ranging, interactive encounter with the cultural history of nineteenth-century America. In addition to electronic reproductions of historical objects and sources—daguerreotypes, illustrations, broadsides, printed books, manuscripts, and the other detritus that would have filled Barnum’s collections—the site includes a series of illuminating short essays on the museum’s social and cultural contexts. Unlike other pioneering virtual archives, such as the ground-breaking American Memory project of the Library of Congress, “The Lost Museum” recreates the experience of a museum from another era, encouraging us to get lost in the artifice of history. For here we are not just viewing a series of documents. We are exploring the particular, sometimes arbitrary ways institutions and scholars link artifacts to larger stories. More than a historical resource, “The Lost Museum” invites us, then, to ponder the narratives with which we stage authenticity, the material objects and practices with which every generation reimagines the kinship of truth and fiction.

Public Leisure and the Print Medium

Barnum remains our most reliable reference point for understanding the struggle between commerce and philanthropy in nineteenth-century America. In her 1997 study of dime museums, for example, the scholar Andrea Dennett baldly asserts, “The answer is clear: Barnum conceived his extraordinary museum for the purpose of entertainment—not education—and with profit as his central concern.” Dennett asserts that “education” and “entertainment” are timeless, discrete categories of experience, rather than concepts developed in the later nineteenth century to justify the mission of civic philanthropy and the modern university. She likewise holds pursuit of profit to be antithetical to a disinterested acquisition of knowledge. Like so many scholars of the American Museum, Dennett makes the outsized personality of Barnum himself—the very image that he so carefully cultivated in print media, in order to market and brand his exhibitions—exhibit A for achieving clarity about the past. In the nineteenth century, however, both producers and consumers of popular knowledge spoke about forms of “rational amusement” in ways that defy simple distinctions between education and entertainment. If Barnum’s name is now synonymous with the tricks of modern advertising, his entertainment succeeded by combining commerce and culture, challenging the simplistic meanings (passive vs. active, imagination vs. utility) that moralists—conservative politicians and evangelical ministers of the early nineteenth century, no less than cultural critics of the twentieth century—would attribute to these concepts.

So how did Barnum fashion American taste? As Neil Harris famously argued, Barnum developed an “operational aesthetic” that made learning about how he pulled off his stunts, hoaxes, and humbugs a major part of their appeal. Amidst rising scientific literacy and populist skepticism of expert learning, Barnum “trained Americans to absorb knowledge” by marketing his museum as an experience of “process,” of problem solving, and of information gathering. Or as another historian, Miles Orvell, puts it, “Learning to tell the true from the false, the lie from the truth, learning trust and mistrust, was part of a process of an acculturation” in a rapidly commercializing America. Another way to think about the value of Barnum’s museum, however, is as an introduction to mass communication, which engaged patrons in a distinctive kind of collective imagination. The latter was being made possible by the confluence of cheap print technology and novel spaces of urban leisure.

To further understand Barnum’s innovations, it is worth attending to his own aesthetic and moral design. To begin with, as he explained in his second autobiography, Struggles and Triumphs, Barnum wanted to attract the largest crowds possible by giving “them abundant and wholesome attractions for a small sum of money.” Like the huge theaters, concert halls, and hotels that competed for antebellum pleasure seekers and tourists, the American Museum sold recreation to “truly mass audiences” that numbered in the thousands. These were, as Harris notes, “heterogeneous groups of men willing to take off their hats and open their pocketbooks for art, but demanding entertainment at the same time.” Although scholars have tended to romanticize these audiences for their raucous, lowbrow, and socially varied character, Barnum suggested that there was no more “truly popular place of amusement” because it was “wholesome” and “attractive” to diverse customers. He “abolished all vulgarity and profanity from the stage,” for example, so that “parents and children could attend the dramatic performances in the so-called Lecture Room, and not be shocked or offended by anything they might see or hear.” And unlike most museums and concert halls, he banned the sale and consumption of alcohol from his galleries. He even hired private detectives to eject men who were drunk or women suspected of prostitution. Barnum made urban leisure safe for everyone.

Using print in innovative ways, Barnum’s promotions turned a visit to his museum into a new kind of imaginative experience. Barnum’s own repeated avowal of a profit motive—so often used to impugn techniques of modern advertising as amoral—underscores the fact that the ends of publicity were more instrumental than symbolic: to mobilize the actions of large groups of people. With commercial signage, broadsides, sandwich boards, and printed money, “a vast spectacle of writing and print [became] part of everyday life in the city by the 1840s and 50s,” the historian David Henkin writes, and Barnum’s “bold lettering and eye-catching graphics” made him, “quite literally, an urban man of letters.” Barnum understood that he owed his success to the “means of printer’s ink, which I have always used freely,” and that advertising was integral to the museum spectacle. Like modern marketing gurus, Barnum understood that he was not just selling particular goods or services. He was selling stories that heightened expectations and speculations about those goods and services. In short, Barnum beat his competitors by telling much better stories about his attractions. “My ‘puffing’ was more persistent, my advertising more audacious, my posters more glaring, my pictures more exaggerated, my flags more patriotic and my transparencies [or illuminated banners] more brilliant.”

Barnum repeatedly justified any particular fabrication that he advertised by pointing to the cumulative experience afforded by the museum. While extending the museum walls outward into the heterogeneous social and physical urban environment, the images and words of his printed advertising and planted “news” were always linked to a collection of bona fide objects and attractions, “a wilderness of wonderful, instructive and amusing realities.” Customers always got their money’s worth because they were only paying twenty-five cents, and there was always more to see. In his first autobiography, published in 1855, Barnum declared, “If a sight of my ‘Niagara Falls’ was not worth twenty-five cents, the privilege of seeing the most extensive and valuable museum on this continent was worth double that sum to any one who was enticed into seeing it by the advertisements.” If the exhibits fell short of what was promised, how much would you pay for another chance to trade in incredulity and wonder? Barnum shrewdly perceived the value of irrationality in a country that, as he put it, was overwhelmed by “a severe and drudging practicalness . . . [that] concentrates itself on dry and technical ideas of duty, and upon a sordid love of acquisition—leaving entirely out of view all those needful and proper relaxations and enjoyments which are interwoven through even the most humble conditions in other countries.” Barnum made sure his customers saw past the objects themselves to become participants in his public theater of the imagination.

Imagination and Virtual Experience

No less than Barnum’s museum, contemporary Web design entails the management of crowds. Because it is interactive and open ended, the user-friendly desktop computer has made our encounter with virtual space a matter of the hand-eye coordination we bring to moving cursors and clicking mice. For the rising generation of digerati, weaned on the ever-more seamless simulacrum of live-action and video animation, the intensive manipulation of on-screen images can itself seem awkward, an oddly old-fashioned way of encountering the past through artifacts that challenge the sophistication and flexibility one complacently assumes in the seemingly personal control of technology. For those unused to the rapid-response demands of Gameboys or the hair-trigger sensitivity of Xbox toggle sticks (or who can barely handle the remote control for home video and audio systems), what one finds in “The Lost Museum” often entails getting lost on the Internet. Accidentally pushing the wrong button or scrolling too haphazardly will—like following the strategic (mis)direction of Barnum’s famous “To the Egress” sign, which led some of his less literate (often Irish) visitors out a back door in search of a potential curiosity—land you on the sidewalk.

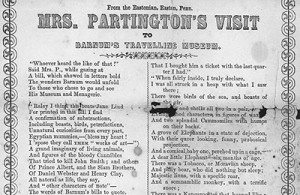

As with “The Lost Museum,” the navigation of Barnum’s collection in the nineteenth century assumed literacy in modern rituals and modern communication forms. Consider, for example, a broadside reprinted in the 1850s from a newspaper called the Eastonian, taken from the work of the American folk humorist Benjamin Penhallow Shillaber. The broadside narrates a visit to Barnum’s traveling museum in the voice of a censorious older woman, Mrs. Partington, who in a series of books had become a popular comic figure known for malapropisms and homespun wisdom. Throughout the first half of the text, this woman’s approach to the museum is clothed in elaborate, if not fanciful, words and phrases—”retrocession into the place,” “reproaching the tent,” “money I’d given him to pay his dismission”—that strain the particularly spoken coherence of common sense and the simple poetry of marketplace doggerel. But once inside the museum, Mrs. Partington is seduced by the visual wonder of the collection: “I truly declare, I was all struck in a heap with what I saw there.” These awkward verbal formulations give way to what Miles Orvell calls the “omnibus form” of descriptive detail, in which the arbitrary juxtaposition of objects is made natural by the merely rhythmic cadence of nouns and names:

Suits of armor, coats of mail

Together with the end of a comet’s tail,—

An Indian canoe, with a curious paddle,

A Mexican uniform, bridle and saddle,

The Point of an argument, wonderful shells,

And a Chinese pagoder all covered with bells.

If Partington’s entrance in the broadside, like her approach to the collection, is skeptical—”‘Whoever hear the like of that!’/Said Mrs. P . . .”—she leaves it in silent reverie:

The old lady, lost in admiration

Here cut the thread of her narration,

And spreading her handkerchief over her face,

And replacing her needles, in her tin netting case,

Settled to sleep, and to dream of Tom Thumb

And the wonders of Barnum’s great museum.

As a byproduct of the notoriety Barnum’s showmanship had achieved, the broadside suggests how fully Barnum’s exhibitions were already touring an information highway. Partington’s visit begins with her “gazing at a bill, which showed in letters bold the wonders Barnum would unfold . . .” Here, as in so much of the publicity that surrounded the American Museum, Barnum’s own reputation for promotion—and especially his facility with the “bold letters” of printer’s ink—is literally built into one’s encounter with the museum, providing the printed frame within which the retailing of goods and leisure “unfold” as “wonders.” But by animating its depiction of Barnum’s museum with extended quotation of Mrs. Partington, the broadside situates our understanding within the local networks of vernacular speech. What one knows in such a world is always filtered through the homely, colloquial social matrices of gossip, conversation, controversy, and argument that spread the popular taste for antebellum entertainment (no less than politics and literary sentiment) by word of mouth. As Barnum himself so often put it, the key to success in the business of culture was “to make people talk and wonder.”

What separates Mrs. Partington’s virtual experience of imagination from our own are the material frameworks through which audiences see and interpret objects. As recent scholarship by Benjamin Reiss, James Cook, and Bluford Adams has demonstrated, nineteenth-century audiences made sense of exhibitions such as the elderly former slave Joice Heth (billed as “Washington’s Nurse”) and other curiosities both living and dead by drawing on contemporary narratives about race, politics, and the exotic. But situated within the motley collection of the American Museum, objects continued to appeal to the traditional cult of the marvelous. As the literary critic Stephen Greenblatt has characterized that pervasive phenomenon, it is the “power of the displayed object to stop the viewer in his or her tracks, to convey an arresting sense of uniqueness, to evoke an exalted attention.” Much like its ancestor, the Renaissance cabinet of curiosity, the American Museum made the beautiful and the strange kindred forms. In doing so, it affirmed the power of man, nature, or the divine to defy the routine patterns and familiar assumptions of reality.

Objects displayed in museums today, by contrast, evoke the original contexts from which they were taken: the church wall, the royal burial chamber, the archeological dig, the vanished habitat, the ceremonial rituals of pre-modern tribes. They carry a resonance of otherness, differences of context and use that can only be partially recovered by catalogue descriptions and exhibition labels, whose very muteness endow objects with transcendent value as historical and aesthetic artifacts. We are expected to know their meaning mainly by silencing the informal narratives within which untrained viewers such as Mrs. Partington unfolded and circulated the social sense of Barnum’s wonders. Narrated within galleries organized by historical period, national context, artistic provenance, or stylistic tradition, objects became artifacts, whose authenticity and value are framed by omniscient scholarly narratives. As they came to be lit by boutique lighting pioneered in shop windows and department stores, these objects demanded the viewer’s deference to symbolic, immanent values, which—whether animated by the spirit of civilization, history, or an emerging anthropological sense of “culture”—divorced an artifact’s meaning from the vernacular networks through which Mrs. Partington would have grasped Barnum’s wonders.

The modern infrastructure of public culture thus gives us wonder without talk, specialized kinds of historical and aesthetic education mediated less by the operations of vernacular speech and popular taste than the methods and institutions of professional expertise. Museums of natural history, for example, introduced formal taxonomies into the preservation and display of collections. “It is not the objects placed in a museum” that constitute its value, as William Henry Flowers, a director of the British Museum argued. It is “the method in which they are displayed and the use made of them for the purpose of instruction.” Similarly, as historians and librarians, such as Harvard’s Justin Winsor, imported German methods to the American academy, a new “scientific history” displaced romantic narratives with documentary evidence that, as historian Steven Cohn notes in his intellectual history of late nineteenth-century American museums, “emphasized detail over values, facts over ultimate meanings.”

Converted into such documentary evidence, objects not only present arguments about the past, but become totems of professional authority, offerings at the alter of positivist objectivity, licensed and guarded by professionals and institutions of higher education. Throughout much of the twentieth century, ordinary people thus learned to see objects not through the screaming letters of broadsides but through the silent reading of books, exhibit labels, collection catalogues, and the like. The apparatus of professional expertise promoted textual truth over the merely antiquarian, the spiritual, and the just plain popular.

Digital Humbug

Seeking “to startle, to make people talk and wonder,” Barnum transformed the marketplace for leisure into a stage for “wonderful, instructive, and amusing realities.” The door of the museum, no less than the two dimensional broadsides that kept it before a mass reading public, was a portal to “realities” that engaged viewers in multiple processes of representation—visual, verbal, architectural, and performative. The speculations that Barnum puffed in print were only consummated when people were motivated to pay the price of admission—the visit by which otherwise standard offerings of mass leisure were made into personal experience. Countless people would leave the museum to write about what they saw in their diaries or letters or simply to talk about their visit with friends and strangers. No matter what they saw, patrons took self-conscious pleasure in the entrepreneurial making and unmaking of meaning.

The digital age has allowed countless museums and libraries to mount exhibitions that travel the information highway but in ways that make the event of a “visit” increasingly passive. Where “The Lost Museum” offers Internet access to a virtual environment, Mrs. Partington traveled to a place:

To see it, and wondered, and marveled

From the first to the last—from morning to night,

And vowed for no money would have missed the great sight.

Today, we can have experiences without actually going anywhere, through increasingly inert and imaginary forms of mobility pioneered in Barnum’s broadsides. Indeed, a New York Timesarticle from July 1, 2000, described “The Lost Museum” as “A Museum to Visit from an Arm Chair.”

Much like the cacophonous nineteenth-century city, every Website assumes the viewer’s ability to navigate particular symbolic codes. In place of the typographic carnival of nineteenth-century broadsides, they trade in the contemporary conventions of the home page, arrayed with icons and lists. They also assume—as does “The Lost Museum”—our facility with the visual and verbal clichés of movies and broadcasting; the faint sound of horses and carriage wheels on cobblestones tells us that we are deep into “history” (any time and place before the automobile), while black darkness signals its vaguely sinister elusiveness (can we ever fully see the past with clarity and objectivity?). Like Caleb Carr’s historical fiction The Alienist (New York, 1994) or Patricia Cline Cohen’s non-fictional history The Murder of Helen Jewett (New York, 1998), the site seeks to popularize the taste for nineteenth-century America by framing its cultural insights and artifacts in the narrative devices of an unsolved mystery: who might have burned down Barnum’s museum? The viewer is encouraged to navigate the documents and artifacts “housed” on the site by gathering clues, which suitably enough are indicated when the screen cursor becomes a question mark. In a clever touch, a notepad, done-up in the antiquated guise of nineteenth-century stationary, is furnished for viewers to record and store their clues, creating a personal narrative about what might have happened and why. With these tools in hand, the viewer becomes his or her own historian. For students, the device offers an elegant education in scholarly method. If the virtual realities of mass communication have removed the social dimension from leisure, Internet technology has, in such inspired sites as “The Lost Museum,” allowed us to regain the sense of wonder that once accompanied a trip to the museum. The site insists that we confront artifacts not as disembodied texts and images—the transcription of handwritten documents or photographic reproductions—but as three-dimensional objects. By moving their cursors across the screen, viewers can reproduce for themselves the increasingly old-fashioned optical effects of walking through a gallery, scanning a wall or room crowded with stuff, zeroing in on a particular object or image, focusing one’s attention on a detail. So too, even in its radically reduced number of artifacts, it recreates the eclectic visual experience of collection, the wonder that Partington attaches to the omnibus form of Barnum’s museum—the sheer quantity of objects linked to one another by the seemingly arbitrary logic of physical proximity, commercial expedience, and connoisseurship.

By blurring the line between entertainment and education, “The Lost Museum” allows us to recover an innovative space in the history of public leisure and popular taste. Ironically, the interactive breakthroughs developed for the Internet have given visitors new tools that succeed as education precisely because they trade in tricks of “rational amusement,” adapting the narrative frameworks and media literacy of modern commercial entertainment. If Barnum’s museum was lost to history, its spirit moves again in the humbugs of digital technology.

Further Reading:

Barnum’s comments can be found in his two autobiographies: P. T. Barnum, Struggles and Triumphs; or, Forty Years’ Recollections of P. T. Barnum, written by Himself (Buffalo, [1876] 1883) and P.T. Barnum, The Life of P.T. Barnum, Written by Himself (New York, 1855). For scholarly assessments of Barnum in American culture, see Andrea Stulman Dennett, Weird and Wonderful: The Dime Museum in America (New York, 1997); Neil Harris, Humbug: The Art of P.T. Barnum (Boston, 1973); Miles Orvell, The Real Thing: Imitation and Authenticity in American Culture, 1880-1940 (Chapel Hill, 1989); David Henkin, City Reading: Written Words and Public Spaces in Antebellum New York (New York, 1998); Benjamin Reiss, The Showman and the Slave: Race, Death and Memory in Barnum’s America (Cambridge, Mass., 2001); James W. Cook, The Arts of Deception: Playing with Fraud in the Age of Barnum (Cambridge, Mass., 2001); Bluford Adams, E Pluribus Barnum: The Great Showman and the Making of U.S. Popular Culture (Minneapolis, 1997). On museum history, see Ivan Karp and Steven Levine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display (Washington, 1991) and Steven Cohn, Museums and American Intellectual Life, 1876-1926 (Chicago, 1998).

This article originally appeared in issue 6.1 (October, 2001).

Thomas Augst is associate professor of English at the University of Minnesota. He is the author of The Clerk’s Tale: Young Men and Moral Life in Nineteenth-Century America (Chicago, 2003) and is currently writing a book about temperance reform and mass culture