Before moving to northern California in 1997, every place I had ever lived was within reach of the Atlantic Ocean. For over three decades, and from various locations across the eastern U.S., the Atlantic had always been within a short walk to a long day’s drive from my home. I was so accustomed to the presence of the Atlantic in my everyday life that I relied on it to determine which direction I was headed. If the ocean was to my right, I was going north; if it was to my left, I was southbound. I didn’t realize the extent of my dependence on it until I moved to California where, in the days before GPS (and as a navigationally challenged human being), the Pacific’s presence on the “wrong” side of the world disoriented me so profoundly that I took wrong turns for years.

The Pacific demanded other adjustments as well. The Atlantic had been swimming-friendly, and I’d spent my childhood seeking relief from the scorching summer heat in its temperate and generally placid waters. The Pacific, however, turned out to be ridiculously cold, dauntingly fierce, and disturbingly unpredictable. I learned there was such a thing as a “rogue wave” that could unexpectedly arise to take an unsuspecting child or dog out to sea. I learned to make a habit of bringing a jacket with me to the beach, even in summer. Only after years of complaining that the water temperature made it impossible to swim did I finally buy a wetsuit, amazed to find this simple adaptation made it possible to enjoy being in the water. Several years afterward, I wore that wetsuit to my first and only surfing lesson, where—after spending half a day falling, over and over again, into an endless series of crashing waves on an overcast and deserted beach—I felt as if I’d finally figured out the Pacific.

Searching for an Early American Pacific

But I had moved to California in the first place to take up a position as a professor of early American literature, and it took even longer to change the syllabi and research projects that defined my work as a teacher and scholar. My teaching and research had always engaged, I thought, with a fairly wide-ranging representation of the early American literary landscape: texts by and about early European travelers and explorers, indigenous peoples, the Puritans, settlers and creoles and citizens in New England and the South, the Caribbean and the wider Atlantic world. These texts, however, rarely got me and my students—most of whom are from California and other western states—any farther from the Atlantic than the first three decades of my life had. If none of my students ever complained, I suspect it’s because they all shared the assumption that there was no early American literature from or about the Pacific (at least not until well into the nineteenth century, when a New Yorker named Herman Melville who had spent some time on whaling ships began to write and publish fiction).

It was when I was beginning a new research project on the early American novel in the context of the Atlantic during the age of revolutions that, ironically, my own assumptions about the early American Pacific began to change. At the time, my office was filled with library books on the revolutionary Atlantic waiting for me to read, and I was preparing to teach a selection of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century novels in a course on revolution and the American novel. That’s when one of my colleagues arrived at my office door with a handful of titles published by Heyday Books, a Bay Area press long dedicated to reprinting forgotten California writing. The title of one of these volumes in particular caught my eye, largely because of its date: Life in a California Mission: Monterey in 1786. Who was in Monterey in 1786, I wondered, and what exactly was life in California like then?

The slim volume turned out to be an account by the French explorer Jean-François Galaup de Lapérouse of his visit to the Spanish mission in Monterey. He described its priests and the mission system, as well as the animals and plants of the region. He also commented on the relationship of the Franciscan priests to the native population, going so far as to suggest that it would not be surprising if the latter were to rise up in rebellion one day. I wondered why a French explorer was on the coast of northern California at all in a period when revolutionary upheavals were taking place around the Atlantic. That question led me to discover that this small book was in fact only a tiny excerpt from Lapérouse’s journals describing his three-year circumnavigation of the globe, taken on behalf of the French crown—and in competitive response to the British expeditions by James Cook—to pursue scientific discovery and prospects for trade in the Pacific.

New Texts, New Maps

When I finally located a reprint edition of Lapérouse’s complete, two volume text, I found myself reading about places that no anthology or history of early American literature had ever taken me—the ports of Cavite and Manila, the island of Formosa, the peninsula of Kamchatka, the Ladrones, the Moluccas, the Society and Solomon Islands. Even when I recognized these names, I was hard pressed to identify where in the world they were actually located, much less where they were in relation to the Aleutian or Hawaiian Islands, to New Zealand or Indonesia, and to each other. My geographical confusion led me to order a large laminated Pacific-view map of the world from National Geographic, which I thumbtacked to the wall beside my desk and consulted repeatedly as I read. The map itself was a visual introduction to another view of the globe, for whenever I looked at it, I realized not only how incredibly watery the world looks from the middle of the Pacific, but also how remote, small, and marginal locations like Europe, New York, or Washington, D.C., appeared from this perspective. Even as Lapérouse’s journals introduced me to an entirely new eighteenth-century geography, the scholarly apparatus to the Hakluyt Society’s edition alerted me to a new eighteenth-century literary history made up of travel narratives by Spanish, English, Russian, French, Dutch, and American explorers and merchants, who documented their incredibly long voyages and often remarkable experiences in the Pacific.

But I was researching and planning to write a book on the novel and the revolutionary Atlantic. This new material was all terribly distracting—so much so, that I began to invent a future project on the Pacific even though I was only just beginning one on the Atlantic. It was as if I’d been pulled in by some kind of rogue research wave, and as this early Pacific writing began to exert an increasingly powerful rip-tide effect on my imagination, I even contemplated the possibility of abandoning the well-trodden ground of the revolutionary Atlantic altogether for its neglected Pacific counterpart. At moments, I found myself fantasizing about improbably creative ways of smashing these two projects together into a single one. Was there a way to integrate a chapter or two on the revolutionary Pacific into this book? How could I possibly bridge the thousands of nautical miles between the eighteenth-century Pacific and the eighteenth-century Atlantic?

I was forced to drop these worries in order to teach a course on the American novel in the Atlantic world and the age of revolutions—a course I had designed (and for which I had ordered books) many months earlier. Even if I had possessed the time or energy to redesign the syllabus at this point, there were no American novels I knew of set in the Pacific during this period, and as much as I loved reading and teaching Melville, I wanted to focus on these earlier decades and to work with texts that were less well known. As we read Susanna Rowson’s Charlotte Temple, Hannah Webster Foster’s The Coquette, and Charles Brockden Brown’s Ormond, my students and I discussed political radicalism, sexual seduction, the French and American revolutions, counterrevolution, and paranoia. But this time as I made my way through Ormond, I noticed a number of references to Ormond’s military and political activities in Russia that I had passed over before. Why would Brown bother to place his strange villain in such a far-flung location?

Finding the Pacific in the Atlantic

I had been taken to the Russian Pacific earlier by Lapérouse, who left Monterey to continue his voyage into the northern Pacific, including one five-day visit to Castries Bay on the far eastern coast of Russia. He described the Native peoples of Siberia at length, often comparing them to “American Indians” and remarking on the “despotic form of government” practiced there by the Russians. He was invited to a ball held by the governor of Kamchatka—a place name that had sent me to my new map to find a peninsula extending from Siberia into the northern Pacific. Could Brown have known about this part of the world? As it turns out, in the same year that Ormond was published, a magazine edited by Brown (The Monthly Magazine and American Review) included a review of the work of the German playwright August von Kotzebue that mentions his play Count Benyowsky; or, the Conspiracy of Kamtschatka. That drama stages the adventures of the Polish mercenary, Count Maurice Benyowsky, who fought (like Ormond) in the Turko-Russian war and was imprisoned in Kamchatka. (Kotzebue’s son, Otto, would go on to become a navigator who explored and wrote his own extraordinary narrative about the northern Pacific). In Kamchatka, Benyowsky seduces the daughter of the governor before escaping with other political prisoners into the Pacific with plans to head for Madagascar.

The play is based on Benyowsky’s own exciting if improbable memoirs, first published in French but later widely available in translation. In Kotzebue’s play, one of Benyowsky’s fellow prisoners keeps a copy of George Anson’s Pacific travel narrative, and the inmates fantasize about escaping to begin their own society on the island of Tinian, which Anson describes as a paradise of freedom where one might begin a new society. The Monthly Magazine article includes a footnote mentioning another play by Kotzebue titled La Peyrouse, which tells the story of the French navigator’s shipwreck in the Pacific, his Pocahontas-like rescue by a native woman named Malvina, and his marriage to her before his French wife arrives on the island, Miranda-like, after years of searching for him. The play ends with the two women proposing to live with Lapérouse in a series of three huts on the shores of this remote Pacific island, a kind of early modern south Pacific Big Love.

Brown’s later interest in Pacific utopias has been well established by scholars, but it was starting to look like that interest was already embedded in the earlier Ormond, whose titular character began more and more to resemble Benyowsky, that globetrotting political and sexual radical associated with East Indian commercial schemes. There was a global and transoceanic awareness in Brown’s novel that resonated with a version of late eighteenth-century Philadelphia I would only later come to learn more about: as the North American port most identified with high-profile trade to the East Indies, and as a city filled with merchants who had made astonishing fortunes (and others who had suffered great losses) from that trade. If I’d never noticed these textual and contextual elements before, it was because I’d been so preoccupied with the novel’s—and the city’s—Atlantic dimensions.

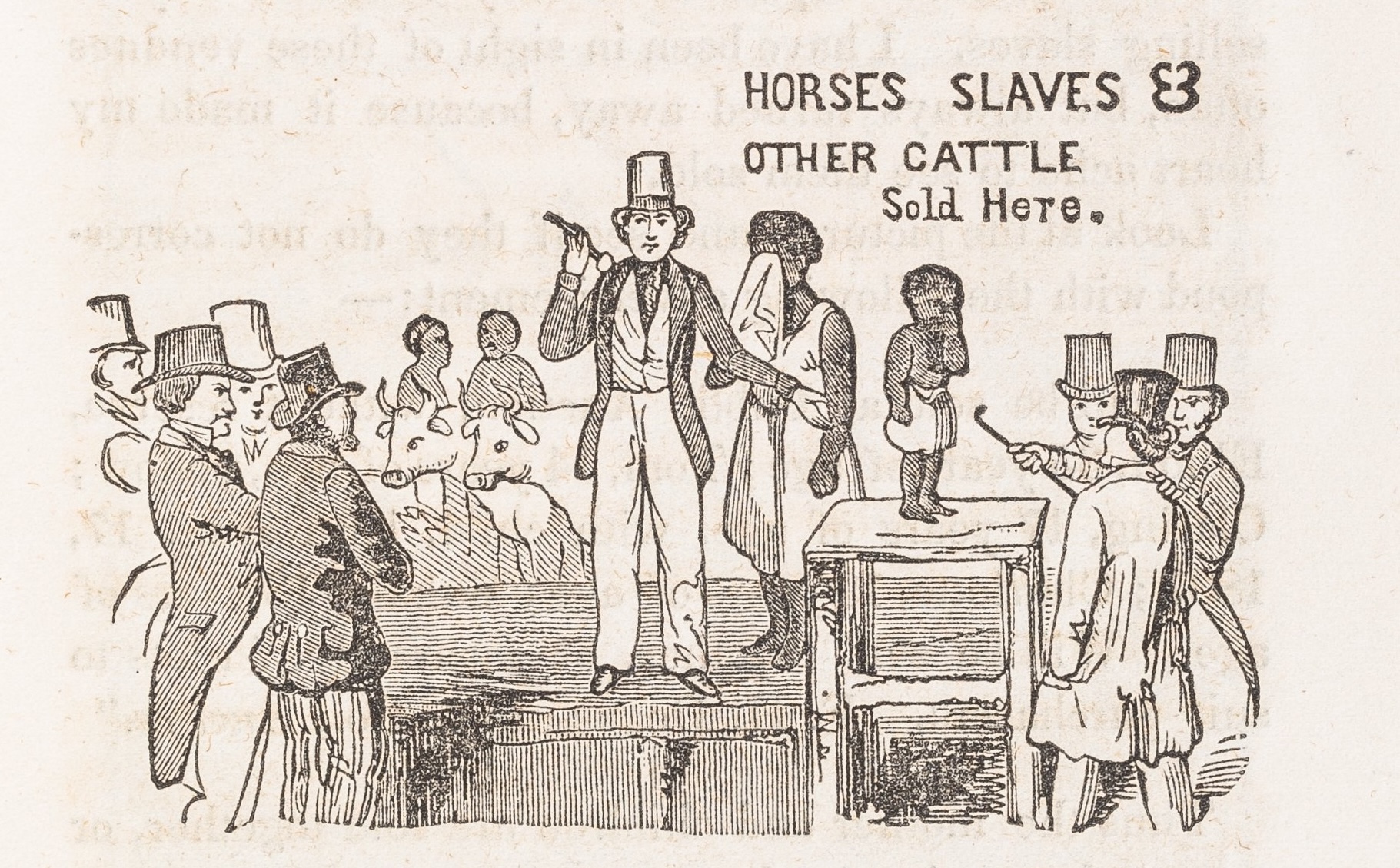

These intertextual discoveries opened up the prospect of writing a book chapter on Ormond in transoceanic context that would allow me to bring the Atlantic and Pacific together in the age of revolutions after all. But that was possible only because there were references to relevant geographical locations in Brown’s novel that I simply hadn’t noticed earlier, before dedicated reading in Pacific materials from the period had alerted me to their names, their significance, and the various texts and figures associated with them. The syllabus for my course moved from Ormond to William Earle’s 1800 novel Obi; or the History of Three-Fingered Jack—a novel about a slave revolt set in Jamaica which sustained an Atlantic awareness but which made absolutely no reference to and possessed no awareness whatsoever of the Pacific. I would have to seek out other novels instead if I wanted to pursue this new course.

It’s difficult for me to reconstruct exactly what happened as I read and taught Obi that quarter, and as a web of informing texts opened the novel up for me and connected it to the Pacific in completely unexpected ways over the following months. But I know it began with the novel’s curiously long footnote on the plantain tree, which appears in a description of the mountain hideaway of the heroic rebel Jack. The note was so disproportionately extensive that it eventually led me to notice the book’s other references to plant life and use of botanical language. I still wasn’t sure what to make of these when I noticed that one of the anti-slavery epigraphs on the original title page was attributed to a book by Erasmus Darwin called The Botanic Garden. I was intrigued enough to take a look at the complete text, and when I accessed it online via Project Gutenberg, I found what seemed to me an astonishing oddity: a two-volume poem, accompanied by a voluminous set of prose footnotes, that was at once a global encyclopedia of botanical knowledge, a manual to the sexual and reproductive lives of plants, and a searing environmental and political treatise about revolution. As I read more about this Darwin (the grandfather of Charles) and the eighteenth-century vogues in botanical collection and classification, my research quickly brought me to the Pacific. Numerous European transoceanic voyages (like that of Lapérouse) were spurred in part by the problems of revolution and slavery in the Atlantic, and they traveled to the Pacific in search of new products and markets. Among these were plants, highly sought after as profitable food, medicine, and luxury items.

The Pacific Breadfruit and the Atlantic Slave Trade

In the wake of the American Revolution, when Britain’s Caribbean sugar colonies were cut off from food imports from North America, Joseph Banks—who gained fame by returning from Cook’s first voyage with numerous new plant specimens (as well as sexualized accounts of indigenous women)—proposed to solve the problem of feeding the West Indian slave population by transplanting breadfruit from the Pacific island of Tahiti to the Atlantic’s plantation zone. He sent William Bligh on a ship named The Bounty on this voyage, a voyage which ended, of course, in what is perhaps the world’s best-known shipboard revolution. But Banks and Bligh tried again, and seven years before Obi was published, Bligh arrived in Jamaica with 66 breadfruit trees that were carried overland to the botanical garden of a planter named Hinton East. A 34-page catalogue of the contents of East’s garden was printed in several editions of Bryan Edwards’ popular History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies in the West Indies, an acknowledged source for William Earle’s Obi in which Edwards also compares Jamaica with Tahiti by drawing on John Hawkesworth’s collection of British Pacific voyages. Which brings us back to plantain.

Most accounts of the breadfruit scheme end by wryly observing that the project failed because slaves refused to eat the food, preferring their regular fare of plantain instead. By the time the breadfruit plants arrived in Jamaica, slaves had long been maintaining provision grounds where they grew plantain and other foodstuffs. Earle describes provision grounds in another, shorter footnote in his novel, and the fact that Jack’s medicine, food, and furniture all consist of plantain products suggest that his hideout is at or near a provision ground, a location often associated also with practitioners of obeah, the hybrid medical-spiritual practice from which the novel takes its title and from which its hero derives his revolutionary political power. The Pacific may not have been anywhere in the text of Obi, but it was there in many of the books on which it relied, there in the Jamaica in which its story was set, and there in the Atlantic world in which it was written and read.

By now, I realized that even though I was reading the same novels I’d read earlier, I was reading them differently, with a transoceanic awareness developed from my immersion in a variety of scientific, commercial, ethnographic, literary, and historical texts about the Pacific. It’s not that I found the Pacific everywhere; it was nowhere to be found in Foster’s The Coquette, as far as I could tell, and it didn’t seem to be present in Rowson’s Charlotte Temple, either (although Rowson’s brother Thomas Haswell did travel on three transoceanic voyages from Boston which took him to the Pacific Northwest, the East Indies, and Canton, China). But I was seeing the Pacific in all kinds of places I had never noticed before. Even novels that did not engage with that ocean’s concrete particulars often reflected the anxieties, interests, pressures, and possibilities of a world in which the Pacific had taken on a new importance, both on its own terms and in relation to the Atlantic. I began to remember the Pacific dimensions of other eighteenth-century texts where its importance has been diminished or forgotten, largely because as teachers and scholars we’ve been so focused on looking in other directions. Although it’s set in the Atlantic, Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe is based on Pacific stories of shipwreck, including that of Alexander Selkirk, who lived on the Pacific island of Juan Fernandez. The fantastic locations of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels are set in a very real geography, where Brobdingnag is positioned as a peninsula extending into the Pacific from the coast of North America, a kind of geographical mirror to Kamchatka. These canonical novels had forgotten counterparts, like the delightfully weird 1778 anonymous novel The Travels of Hildebrand Bowman, set in a series of imaginary south Pacific locations, including the continent named Luxo-volupto, where women sprout wings on their heads once they’ve seduced a man, and where the colony of Armoseria has risen up in rebellion against its indulgent and corrupt mother country—an obvious allegory for revolutionary America.

Is the Pacific American?

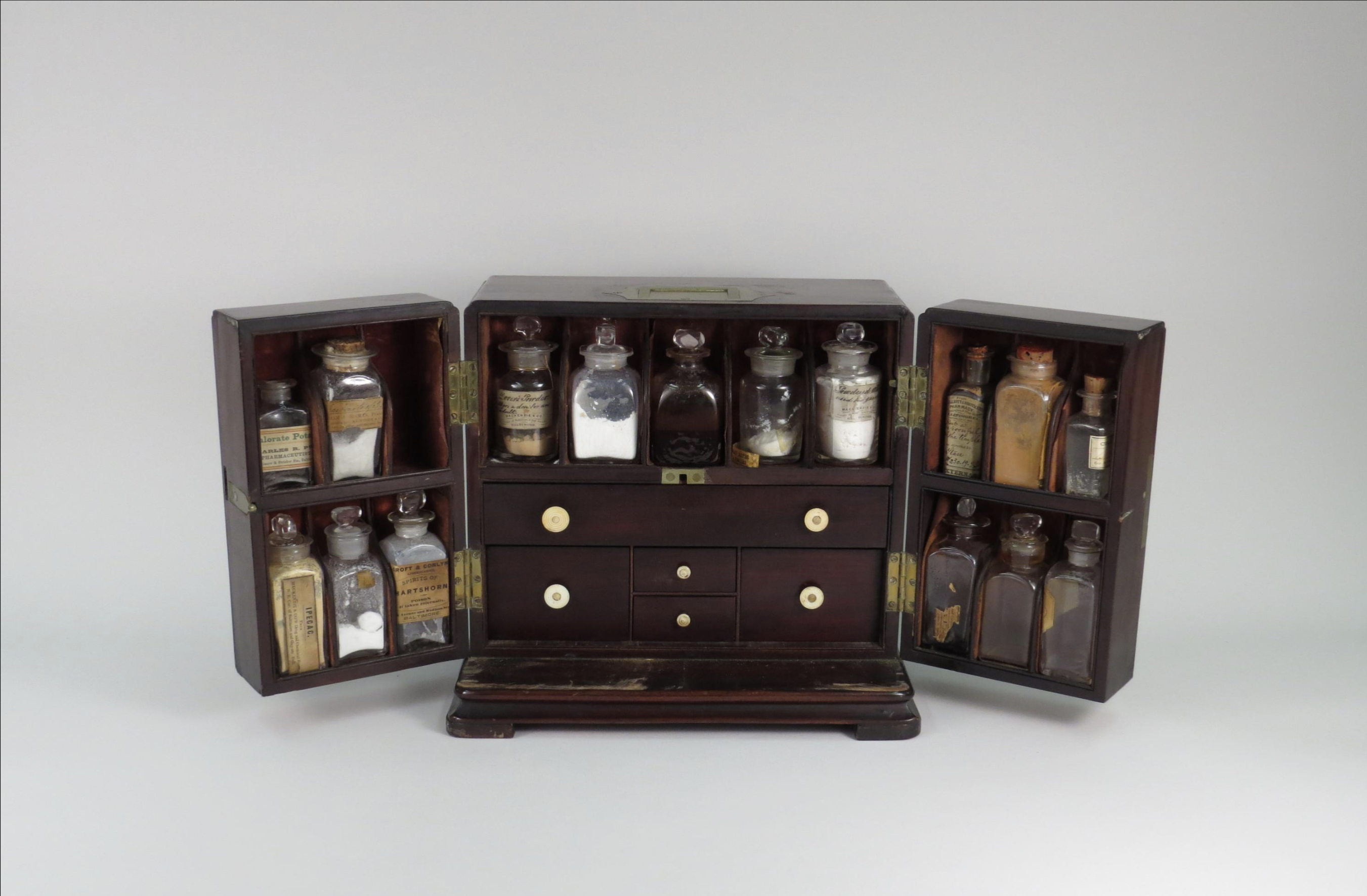

While I had found the Pacific in some surprising textual locations, I often faced a question posed to me as an Americanist working with this array of international texts written in (and translated from) multiple languages. In what possible sense were these American texts? Brown’s Ormond might seem unarguably American, but what about its sources? These included the narrative of a Polish-Hungarian count imprisoned in Siberia, written in French. English translations were published in book form in London and Dublin, in abridged and serialized form in a New York periodical, and advertised in Boston for potential subscribers. Benyowsky’s story was also turned into a play by a German playwright, translated and performed in London, reviewed in Philadelphia, and later performed in Baltimore on the same night that the Star-Spangled Banner debuted. Why Baltimore? Likely because that was where Benyowsky established a mercantile firm for commerce in slaves, and from which he sailed on his way to Madagascar—where he would be killed by the French. This isn’t an American text, but is it a Polish one? A French one? An English one? We might ask the same questions of the Pacific travel narratives by Lapérouse, Cook, Bougainville, and many others, which were similarly translated, abridged, serialized, and adapted into a variety of languages and forms. Many of those narratives and voyages are cited in the footnotes that populate Erasmus Darwin’s Botanic Garden, revealing his reliance on an international archive of travel narratives and natural histories that spanned the globe by crossing its oceans. Darwin’s book was published in London in 1791, and its first American edition was edited by Elihu Hubbard Smith, the physician who was also the close friend and onetime roommate of Charles Brockden Brown, whose novel Ormond appeared a year later.

Like the seeds of plants or radical revolutionary ideas, these texts traveled—they were translated, transplanted, renovated, revised. Labeling these texts with a single national marker, or limiting their identification to a single language or version, actually prevents us from following their routes of travel and transformation. Many of these texts will never make their way into American literature anthologies, nor should they. They represent an understanding of literary history that really can’t be represented by the form of the anthology, much less by any national, linguistic, or even continental designator. In fact, such designators often help to ensure that scholars and students of American literature will never encounter or engage with texts like these at all, much less venture into the tangled webs of their textual and intertextual histories. Anthologies and readily available editions might be thought of as home ports, familiar shores, from which students should be encouraged to depart in order to explore connections that can bring them to unfamiliar archives and unexpected locations. Sometimes we find new ways of seeing by facing the wrong direction.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Juliana Chang, Jackie Hendricks, Claudia McIsaac, and Robin Tremblay-McGaw.

Further Reading

The Pacific Routes issue of Common-place offers an excellent introduction to the early Pacific in the context of American studies. The two-volume Journal of Jean-François de Galaup de la Pérouse, 1785-1788 has been translated and edited for the Hakluyt Society by John Dunmore (London, 1994). Charles Brockden Brown’s Ormond is available in an exceptionally well-documented edition prepared by Philip Barnard and Stephen Shapiro (Cambridge, Mass., 2009). The two best introductions to Benyowsky are his own two-volume Memoirs and Travels of Mauritius Augustus Count de Benyowsky (Dublin, 1790), and August von Kotzebue’s Count Benyowsky; or, the Conspiracy of Kamtschatka, 2nd ed., trans. William Render (London, 1798). James R. Fichter’s So Great a Proffit: How the East Indies Trade Transformed Anglo-American Capitalism (Cambridge, Mass., 2010) and Jonathan Goldstein’s Philadelphia and the China Trade 1682-1846: Commercial, Cultural, and Attitudinal Effects (University Park, Penn., 1978) provide fine introductions to America’s and Philadelphia’s early involvement in the East Indies trade. Srinivas Avaramudan’s edition of William Earle’s Obi; or the History of Three-Fingered Jack (Peterborough, Ontario, 2005) is usefully read alongside Erasmus Darwin’s two-volume 1791 Botanic Garden (New York, 1978) and Edward Long’s 1774 History of Jamaica (New York, 1972). Beth Tobin’s Colonizing Nature: The Tropics in British Arts and Letters, 1760-1820 (University Park, Penn., 2005), Jill H. Casid’s Sowing Empire: Landscape and Colonization (Minneapolis, Minn., 2005), and Glynis Ridley’s terrific Discovery of Jeanne Baret: A Story of Science, the High Seas, and the First Woman to Circumnavigate the Globe (New York, 2010) provide excellent studies of botany, plant collection, and transplantation in transoceanic context. And look out for the forthcoming reprint of The Travels of Hildebrand Bowman from Broadview Press, edited by Lance Bertelsen.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.1 (Fall, 2015).

Michelle Burnham is professor and chair of the English Department at Santa Clara University. She has published widely on early American literature, and is currently completing a book on transoceanic American writing and the revolutionary Pacific.