John Ledyard was ill and haggard. His normally erect frame was bent, making him look years older than his thirty-eight. His hands and arms were mottled with a series of closely placed reddish brown dots (tatau, or “tattoo,” as Captain Cook transcribed the Tahitian word) that resembled a tailor’s pattern for cutting fabric and that he had acquired while sailing with Cook. He carried a heavy overcoat, boots, and socks made from reindeer hide; a fur cap; and a pair of fox-skin gloves lined with rabbit fur. He was penniless, expecting, as he had for most of his days, that friends and acquaintances would provide the essentials of life. Aside from his clothing, his only valuable possession was a travel diary he had kept during his previous two years’ journey.

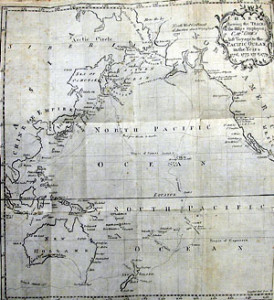

That journey had taken him overland from London to the Russian city of Yakutsk and then back to London, more than ten thousand miles in total. It was a journey Ledyard undertook alone, intending to survive through sheer determination and the good will of strangers. It was also an incomplete journey. Ledyard had planned to travel across Europe, Russia, Siberia, and the Russian Far East to the Pacific Ocean, and from there to reach the North American continent. He had hoped to become the first man to traverse the continent, traveling from west to east alone and on foot and depending on his limited knowledge of American-Indian languages and customs for his survival. He would collect scientific readings not with instruments and notebooks but with a crudely fashioned sextant and a pointed, stained stick, using the latter to tattoo on his body the coordinates of various landmarks.

Sadly, or perhaps fortunately, the trip was cut short. Russian authorities expelled Ledyard from their dominions before he reached the Pacific Ocean.

His return to London in December of 1789 was nonetheless a happy occasion. For he was greeted with news that a prominent British antislavery activist had formed the Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa. And the Association was pleased to employ Ledyard to journey to the headwaters of the Niger River, for which he would be paid a modest stipend and, if successful, would achieve the kind of celebrity he craved. He would also, he assured his patrons, return to the America in which he was born and attempt once again to traverse its great expanse. “He promises me,” wrote Thomas Jefferson, then American minister to France, “if he escapes through this journey, he will go to Kentucky and endeavour to penetrate Westwardly from thence to the South sea.”

He was, we all know, unable to keep his promise.

A misdiagnosed stomach ailment took him before he ever made it to inner Africa. The honor of making that journey would go to the great Scottish explorer Mungo Park. And the honor of crossing the American continent would not go to a lone traveler, banking on little more than native wit, but to Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the two American military officers later commissioned by the federal government to explore America’s unknown West.

I.

In death, John Ledyard numbered, for a time, among America’s most celebrated sons. Through the early 1790’s, glosses of his life, his letters, and his unpublished writings appeared in American newspapers and gentlemen’s magazines. And the New York editor and poet Philip Freneau solicited subscriptions for an edited collection of Ledyard’s writings, a project he never completed.

In 1828 Jared Sparks, the Unitarian pastor and eventual president of Harvard College, published the first life of Ledyard. The biography represents the culminating moment in America’s celebration of this tragic figure. It gave readers a John Ledyard admirable not so much for what he accomplished but rather for the way he lived. Sparks’s Ledyard approached his various and often impossible projects with fortitude and an abiding refusal to be cowed by failure. As summarized in the book’s final paragraph, “The acts of [Ledyard’s] life demand notice less on account of their results, than of the spirit with which they were performed, and the uncommon traits of character which prompted [him] to their execution. Such instances of decision, energy, perseverance, fortitude, and enterprise, have rarely been witnessed in the same individual; and, in the exercise of these high attributes of mind, his example cannot be too much admired or imitated.”

Sparks’s Ledyard is thus the supreme romantic hero. His adventures are not inhibited by worldly concerns or fear of physical suffering; like the ancient Stoics or the great saints of Christendom, he freely sacrificed himself for some greater cause. Writing amidst the explosion of market-driven individualism that enveloped Jacksonian America, Sparks no doubt saw in Ledyard a worthy role model for his increasingly materialistic, acquisitive countrymen. But of course there is much more to Ledyard, much that may not have interested Sparks.

Consider the following: beneath the stoic adventurer was a man in every way a product of that larger entity we have come to call the British Empire. Ledyard was born in the British colony of Connecticut. His family was thoroughly dependent on the British West Indies trade. His working life began aboard a merchant vessel plying the British Atlantic triangle trade. And his career as traveler and explorer was thoroughly intertwined with the British pursuit of empire. Captain Cook’s third Pacific expedition would never have happened had the Admiralty, the agency charged with protecting Britain’s oceanic trade, not sought easier routes to the rich Pacific basin. And Ledyard’s final two undertakings, the attempted crossing of North America and a journey to Africa, depended partly on the patronage of Britons whose imperial vision was refracted through the benevolent pursuit of scientific facts.

Ledyard was no innocent, unconscious pawn in all this. For in addition to being a product of empire, he was, or at least struggled to be, an agent in empire’s growth. As a lowly British marine, an author, a businessman, a traveler, and explorer, Ledyard looked to the Pacific. It was that vast, rich region that would raise this New Englander from obscurity and poverty.

In addition to a story of self-sacrifice, Ledyard’s biography is thus the story of thousands of Britons who came to see in empire not simply an abstract structure of the sort the American Revolutionaries attacked, but also a source of opportunity: opportunity for personal betterment, for self-realization, for wealth and honor, for all of those things that young Anglo-American men so desperately sought during the latter part of the eighteenth century.

For Ledyard, that is, empire was another arena in which young men could fight to achieve distinction and notoriety, an arena like other new frontiers of individual attainment, including the art market, the popular theater, and Grub Street. The latter proves especially important since Ledyard’s imperial life was equally a life of writing. Everything he did, whether sailing with Cook, crossing Siberia, or promoting the Northwest-Coast fur trade, depended on his ability to translate experience into prose. The written word, as much as patronage or trade, provided the sinews of John Ledyard’s imperial world.

II.

John Ledyard was born in Groton, Connecticut, in 1751, the son of a sea captain and the grandson of one of the colony’s most prominent politicians and magistrates. His early childhood was uneventful, punctuated by the comings and goings of his seafaring father. In 1762 when smallpox took Captain Ledyard, young John’s mother Abigail sent him, her eldest son, to live with his grandfather in Hartford.

A decade later, family connections allowed John to attend Dartmouth College, recently founded in the woods of central New Hampshire. But financial problems and personal clashes with Eleazar Wheelock, the college’s founder, led John to withdraw a year and a half after arriving at Dartmouth. Inspired by his intensely pious mother, John attempted to apprentice for the Congregational ministry, but finding no willing sponsor and desperate for work, he signed on as a common seaman aboard a New London merchant ship. In early 1776, John found his way to England on a fruitless search for wealthy relatives. As an able-bodied man with neither money nor an official letter of introduction, he became a target of Britain’s ceaseless battle against idleness. In Ledyard’s case, that battle meant a choice between life in the army or in the convict colony at Guinea.

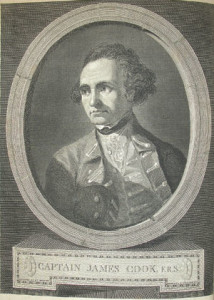

Ledyard chose the former but after his unit was ordered to leave for Boston to help put down a colonial rebellion, he petitioned for a transfer, claiming that he could not raise arms against his American brethren. The petition was successful and Ledyard was allowed to enlist as a corporal in the marines, those sea-soldiers whose primary occupation was not putting down rebellions in far off colonies but simply preventing them on his majesty’s ships. When the former North-Sea coal-hauling vessel H. M. S. Resolution, commanded by Captain James Cook, arrived in Plymouth at the end of June 1776, Ledyard joined its complement of nineteen marines.

Ledyard came to see that this voyage of discovery offered him more than simply freedom “from coming to America as her enemy.” The payoff for sailing with Cook would come not from any income paid by the Admiralty or from prize money (which was unlikely on a peaceful exploratory expedition), but from what the voyages did for its participants’ reputations. Under normal circumstances, that would come from military valor and sangfroid. But on a voyage of discovery, the young officers, midshipmen, and ambitious enlisted men had to find other ways to achieve distinction.

And many of them found this in an unlikely place: writing. Every crewmember who could do so kept a journal or notes for some future account of the voyage; others produced drawings and crude charts. That Ledyard saw in such writings a potential source of distinction is perhaps best indicated by the testimony of James Burney, brother of the novelist Fanny and first lieutenant aboard the Discovery, the Resolution’s consort ship. In a later account of Pacific exploration, Burney recalled that the American “had a passion for lofty sentiment and description” and that after Cook’s death, Ledyard attempted to persuade the voyage’s new commander, Captain Charles Clerke, to allow him to become official “historiographer” of the expedition. To this end, Ledyard presented Clerke with a specimen of his own ethnographic writing, presumably lifted from his personal journal. Ledyard, however, was unaware “how many candidates he would have had to contend with, if the office to which he aspired had been vacant; perhaps not with fewer than with every one in the two ships who kept journals.”

There is no way to know exactly what that number was. Nearly thirty journals and logs remain from the voyage but it is almost certain that many more such documents have been lost. There might have been those who, like Richard Rollett, a sailmaker on Cook’s second Pacific expedition, kept a journal “Interlin’d in his bible.” But if so, they seem to have suffered the same fate as the writings of James Bligh, master aboard the Resolution. Bligh would have been responsible for hourly entries in the ship’s log and, as was common practice, would almost certainly have kept a running journal, narrating the ship’s daily progress. But none of these are known to exist. Similarly, Ledyard’s own journal, which Burney implies he kept and which was supposedly the basis for his only published book, is lost.

III.

If for the moment, Ledyard’s writing did little to distinguish him, he hoped his conduct would. And perhaps the best indication that that conduct was in fact dutiful and worthy comes from Cook’s own written account of the expedition. Ledyard’s name appears there only once, when he volunteered to travel to a Russian camp on the Aleutian Island of Unalaska. In the brief passage describing the incident, Cook referred to Ledyard as “an intelligent man.” That Ledyard appears nowhere else in Cook’s journals is a testament to his good service since Cook almost never mentioned enlisted men by name unless they died or committed a crime.

Perhaps the young wanderer from Connecticut recognized that through quiet service an obscure enlisted man could—much as Cook, a former shop clerk, had done—rise up the naval hierarchy and achieve for himself the kind of recognition he craved.

After more than four years at sea, Ledyard was given reason to believe that his good conduct had served such a purpose. On September 23, 1780, as the Resolution prepared to return to the naval yards at Deptford, John Gore, the Virginian-born commander who had succeeded the deceased Captain James Clerke, promoted Ledyard to sergeant, the highest noncommissioned office in the marines. It was an act that perhaps emboldened Ledyard to petition the first lord of the Admiralty for an officer’s commission. As he wrote in that petition, “[W]hen I reflect that I can appeal to the testimonies of such as have done honour to our Navy, to the World, and to your Lordship’s Patronage . . . I flatter myself justified in looking upon your Lordship for a reward for my past and an encouragement for my future services.”

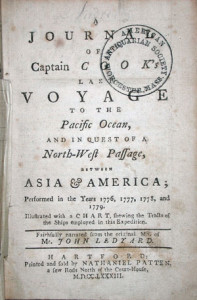

Though supported by the esteemed Gore, Ledyard’s petition failed to move the head of the Admiralty. Instead of an officer’s commission, this dutiful marine veteran found himself posted aboard a frigate cruising the waters off Long Island. Not surprisingly, the temptation of going home would overcome whatever loyalty the rebuffed Ledyard may have had to the navy. And in 1782, he deserted, probably with the help of his mother who lived in Southold, near the island’s northeastern tip. From here, he made his way to Hartford where, in 1783, he published a book entitled A Journal of Captain Cook’s Last Voyage to the Pacific Ocean, and in Quest of a North-West Passage. For the most part, the book is a dry travelogue; it shows little of the “sentimental thought and florid prose” that Burney found in Ledyard’s private discourse.

In early 1783, Ledyard successfully petitioned the Connecticut State Assembly for a copyright (the first ever issued for a book in the United States), apparently fearful that his book’s contents would be pirated. The danger was not so much lost book sales; this was still an age of rampant and unregulated plagiarism. Rather, it was the possibility that someone else would lay claim to knowledge that no other American had and that Ledyard had very good reason to believe would be much valued in the new United States.

The Revolutionary War had left American merchants searching for ways to free themselves from the trade routes of the British dominated Atlantic. And Ledyard had a solution to their problem. Recalling the untapped wealth of Nootka Sound off Vancouver Island he wrote,

[T]he light in which this country will appear most to advantage respects the variety of its animals, and the richness of their furr. They have foxes, sables, hares, marmosets, ermines, weazles, bears, wolves, deer, moose, dogs, otters, beavers, and a species of weazel called the glutton; the skin of this animal was sold at Kamchatka, a Russian factory on the Asiatic coast for sixty rubles, which is near 12 guineas, and had it been sold in China it would have been worth 30 guineas . . . Neither did we purchase a quarter part of the beaver and other furr skins we might have done, and most certainly should have done had we known of meeting the opportunity of disposing of them to such an astonishing profit.

The commercial possibilities of the Pacific were thus nearly unlimited. Those exotic goods, particularly Chinese tea and porcelain, that occasionally made it to North America, usually via Britain, and that were almost unaffordable could now be obtained for the price of a few sea otter skins. And the fur trade, which by the late eighteenth century had nearly vanished from eastern North America, could become once again a viable American business.

The Revolutionary financier Robert Morris found Ledyard’s case persuasive and paid him a modest retainer to secure a ship, crew, and other investors. But after one partner pulled out, Morris too abandoned Ledyard, leaving the former mariner with little hope of finding American support for his costly scheme. Part of the problem was that after Cook’s expedition, the Northwest Coast had become the focus of an increasingly tense dispute between the British and the Spanish. For an unarmed American merchant ship to venture into those waters was thus risky. Perhaps Morris and his colleagues recognized this and, still seeking alternative markets for American goods, decided to find a different route to Asia. They did this shortly after parting ways with Ledyard when on February 22, 1784, the 360-ton Empress of China sailed from New York for Canton. Instead of relying on Northwest Coast furs, this venture relied primarily on ginseng gathered from the New England countryside.

Shortly before the Empress sailed, Ledyard traveled to France in search of other investors, and formed a brief partnership with John Paul Jones, America’s first great naval commander. But nothing came of this and Ledyard found himself in Paris in 1787 with no money and few prospects. Thomas Jefferson suggested that he undertake a very different kind of enterprise, an enterprise that would take him to the Pacific not as a fur trader but as a lone traveler, trekking east across the North American continent.

IV.

If there is more to John Ledyard than Jared Sparks would have us believe, it lies not in Ledyard’s accomplishments, but, as Sparks suggested, in his way of living. To Sparks, the latter suggested stoicism and selflessness. But a fresh look at John Ledyard suggests something more. Far from simply a man of extraordinary determination and strength of character, John Ledyard was a man of his times. Where he went, who he knew, how he traveled, his peculiar talents all reflected processes that drew in people from throughout the British Empire. Even something so mundane as the writing of a travel journal can be understood in this light. Whether sailing with Captain Cook or traveling through the Russian Far East, Ledyard wrote with the expectation that his words would be consumed by men like Robert Morris or Thomas Jefferson, men who could find valuable talent in this strange traveler. It would be through their favor that Ledyard’s fragile purchase in this world would be extended. They would feed and cloth him. And they would affirm his good reputation, assuring him the kind of lasting notoriety that all aspiring men of the age sought. Empire would do for John Ledyard what it had done for so many aspiring young Britons, from Benjamin Franklin to Captain Cook, the fortunate son of an ordinary day laborer. It would make him a man worth knowing. And this was John Ledyard’s supreme desire. Writing to his mother shortly before his death, he observed, “Born in obscure little Groton, formed by nature and education . . . behold me the greatest traveller in history, exccentric, irregular, rapid, unaccountable, curious, and without vanity, majestic as a comet. I afford a new character to the world, and a new subject to biography.”

Further Reading:

Since Jared Sparks’s The Life of John Ledyard, The American Traveller (Cambridge, Mass., 1828), two complete biographies of Ledyard have appeared: Kenneth Munford’s John Ledyard: an American Marco Polo (Portland, Ore., 1939) and Helen Augur’s Passage to Glory: John Ledyard’s America (New York, 1946). Also see Larzer Ziff’s useful sketch in his Return Passages: Great American Travel Writing, 1780-1910 (New Haven, 2000), 17-57. The most comprehensive treatment of Ledyard’s Siberia journey is Stephen D. Watrous’s detailed introduction to his superb edition of Ledyard’s Russia journal and related writings, John Ledyard’s Journey Through Russia and Siberia, 1787-1788 (Madison, Wisc., 1966), 3-87. Also see my “Visions of Another Empire: John Ledyard, an American Traveler Across the Russian Empire, 1787-1788,” in The Journal of the Early Republic 24 (Fall 2004): 347-80. On Ledyard’s years with Captain Cook, see the introduction by Sinclair H. Hitchings to John Ledyard’s Journal of Captain Cook’s Last Voyage, James Kenneth Munford, ed. (Corvallis, Ore., 1963), xxi-xlix.

This article originally appeared in issue 5.2 (January, 2005).

Edward G. Gray teaches early American history at Florida State University and is writing a biography of John Ledyard.