Carwin’s reluctance to take full responsibility for his actions at the novel’s climax presents a significant example. Carwin blames his initial choice to test the Wieland family with mysterious voices on the inspiration of his “daemon of mischief.” You don’t have to squint too hard to see the similarities between daemon of mischief and that familiar Silicon Valley buzzword, disruptor, and what better way to describe his effect on the Wielands than Facebook’s old motto of “move fast and break stuff”? Carwin further denies reponsibility when he tries to persuade Clara that he did not give Theodore the command to murder his family:

Catharine was dead by violence. Surely my malignant stars had not made me the cause of her death; yet had I not rashly set in motion a machine, over whose progress I had no control, and which experience had shown me was infinite in power? Every day might add to the catalogue of horrors of which this was the source, and a seasonable disclosure of the truth might prevent numberless ills. . . .

I have uttered the truth. This is the extent of my offences. You tell me a horrid tale of Wieland being led to the destruction of his wife and children, by some mysterious agent. You charge me with the guilt of this agency; but I repeat that the amount of my guilt has been truly stated. The perpetrator of Catharine’s death was unknown to me till now; nay, it is still unknown to me.

In this dialogue, Carwin displaces the burgeoning responsibility he feels for creating a context that would destroy the lives of the Wieland family. Carwin transitions from recognizing that his imitations exacerbated Theodore’s break from reality to placing the blame on an unknown force. The last line of this passage, where he states that he still doesn’t know who killed Catharine, even as Clara has just informed him that it was Theodore, indicates that Carwin seeks to maintain his belief in a power outside human control.

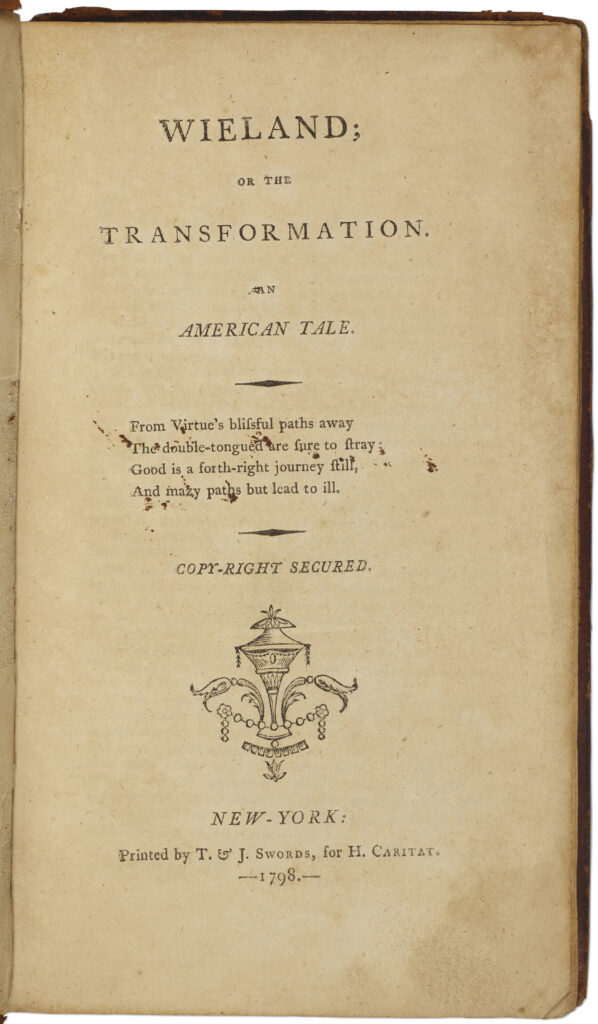

In the novel’s opening paragraphs, Clara tells her unnamed correspondent to: “Make what use of the tale you shall think proper. If it be communicated to the world, it will inculcate the duty of avoiding deceit.” There are plenty of examples of deception within the novel, and Carwin obviously represents an early example of the kind of confidence man that will become so prominent in subsequent American literature. But I don’t think Brown is just urging readers to be more cautious in avoiding scams and grifters here.

Instead, the kind of deceit the novel has in mind is the self-deception that occurs when we cast responsibility outside ourselves and make imagined external subjects responsible for decisions that are ultimately the product of our own cultural choices. Being aware of the possibility of such deceit strikes me as more essential than ever as generative AI becomes part of our classrooms, our workplaces, and our lives more broadly.

Further Reading

Emily Bender, Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell, “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” FAccT ’21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (March 2021): 610–623.

Charles Brockden Brown, Wieland; or The Transformation, ed. Philip Barnard and Stephen Shapiro (Cambridge, Mass.: Hackett Publishing Co., 2009).

Kevin Roose, “A Conversation with Bing’s Chatbot Left Me Deeply Unsettled,” New York Times, February 16, 2023.

Oliver Whang, “How to Tell If Your AI is Conscious,” New York Times, Sept. 18, 2023.

This article originally appeared in April 2024.

James M. Greene is Associate Professor of English at Indiana State University, where he also serves as the Faculty Fellow for Artificial Intelligence. He is the author of The Soldier’s Two Bodies: Military Sacrifice and Popular Sovereignty in Revolutionary War Veteran Narratives (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2020).