This year marks the two hundredth anniversary of the death of Eli Whitney, probably America’s most celebrated inventor after Thomas Edison. Whitney is known for two things: the cotton gin and interchangeable parts. The cotton gin is by far the more famous. Many have been taught that without it, cotton cultivation could not have spread across much of the South. Since cotton was cultivated by enslaved people, and the states most dominated by slavery were that ones that seceded from the Union to protect slavery, it has been said that the cotton gin was a necessary cause for the Civil War.

How Eli Whitney Single-handedly Started the Civil War . . . and Why That’s Not True

The real Whitney story is less grand than the legend, but more interesting and, ultimately, more edifying.

Necessary, but not sufficient. Secession was how southern leaders responded to what they saw as the northern free states’ growing aggression against them. But why did the North threaten the South, intentionally or otherwise? According to another common line of thought, the North was industrializing and didn’t need slavery, which was an old and inefficient way to produce things. Northern industrialists then dragged the agricultural South kicking and screaming into the modern world in a terrible war that could have been avoided.

This is where interchangeable parts come in. Making standardized and identical products–rather than customized and variable ones–is a core principle of industrial production. Practically, this means breaking production down into a series of highly specialized steps and mass manufacturing each component with machines instead of having skilled craftsmen make entire products from start to finish by hand. In this process, each instance of each component must be made with enough precision to be effectively identical to each other instance of that component—that is, parts must be interchangeable. Without this, industrialization as we know it isn’t possible.

It seems remarkable, then, that this one guy—Eli Whitney, the paradigmatic clever Yankee—invented both the cotton gin and interchangeable parts. It’s as if Whitney single-handedly set the South and the North on opposite courses of economic development that later collided with consequences at once deadly, tragic, and emancipatory.

It’s an incredible story. It just happens to be mostly untrue. The real Whitney story is less grand than the legend, but more interesting and, ultimately, more edifying. It dispels several widely held ideas that aren’t very true. First, that the Whitney cotton gin was essential for the rise of the Cotton Kingdom in the Deep South. Second, that the antebellum North was an industrial behemoth that overpowered the agricultural South. And most importantly, that technological innovation occurs in dramatic leaps and bounds made by individual inventors.

The Whitney Legend

There is a commonly repeated legend about Whitney himself, some of which is even true. Let’s start there. According to the legend, Whitney showed signs of remarkable mechanical aptitude from an early age. He was born in 1765 on his parents’ prosperous farm in Westboro, Massachusetts, where he could often be found in his father’s workshop messing about with the tools. By the time he was twelve he had mastered the craft of making nails, which were produced one at a time by hand in that era. He refined his skills by turning his nail-making into a business producing ladies’ hat pins. By this time all the people in the area were beginning to recognize that young Eli was more than an average tinkerer.

Whitney’s ambition led him to study at Yale University, where he excelled at his classes and made connections with influential people. When he graduated, Yale’s president arranged for him to go South to take a job as a tutor for a wealthy planter family. On the way South Whitney met Catherine Green, the widow of Revolutionary War hero and planter, Nathaniel Green. She was traveling with her plantation manger, Phineas Miller, another Yale graduate, whom Whitney quickly befriended. When the tutoring job didn’t work out, Green invited Whitney to stay on her plantation while he figured out his next move.

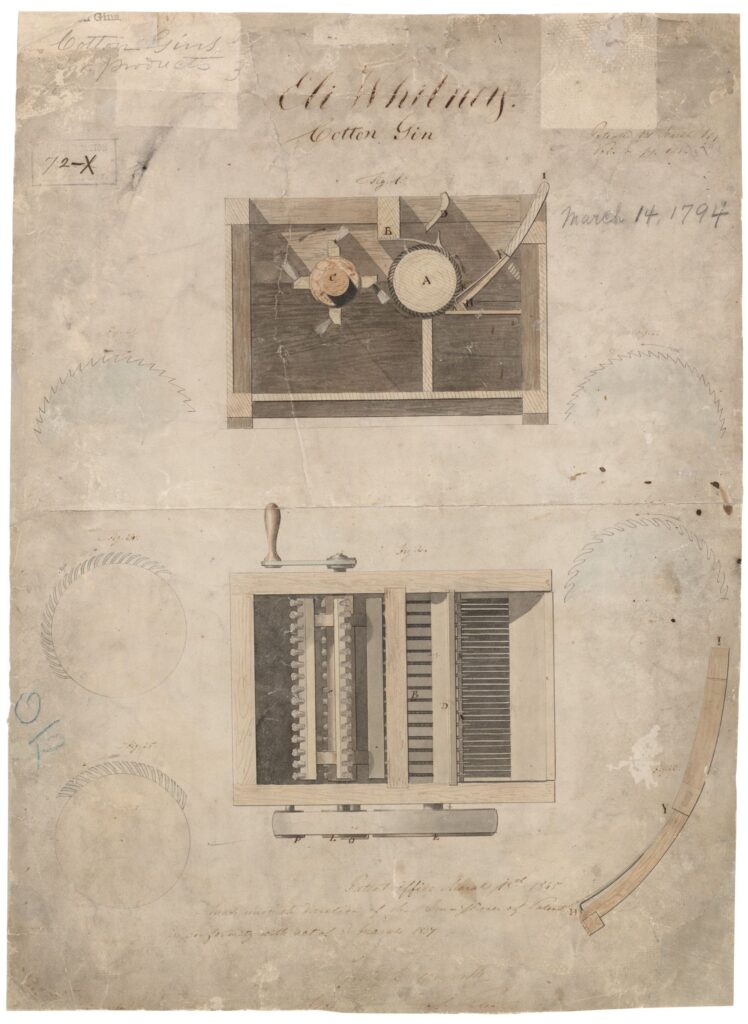

There, the legend goes, Whitney one day hit on the idea of a new kind of cotton gin. Working feverishly and in secret, he perfected the gin in several months and formed a partnership with Miller to patent and profit from it. Although the gin was a mechanical success, numerous patent infringements and lawsuits followed, denying Whitney and Miller their deserved profits and draining their resources. Whitney returned North and ultimately gave up on his first invention.

Instead, he shifted to his second great invention, interchangeable parts, which he pursued after securing an Army contract to produce small arms. To win the contract, Whitney had astounded government officials by displaying ten guns, disassembling their parts and mixing them thoroughly, then reassembling the guns, thus demonstrating that interchangeability was feasible. To go from mere achievability to bona fide achievement, Whitney built a new factory on the principle of interchangeable parts, replacing skilled craftsmen who built guns lock, stock and barrel with ordinary workmen operating specialized machines to manufacture each part, in quantity, to identical specifications.

So goes the legend. What actually happened?

What Actually Happened, Part 1: The Gin

To begin with, we do not really know much of anything about Whitney’s early life. The story of his youthful mechanical aptitude and the details about his nail and hatpin businesses come from a hagiography written by another Yale alumnus, Denison Olmstead, in 1832, seven years after Whitney’s death. Whitney himself never discussed this aspect of his life, at least not publicly in any surviving record. It seems reasonable to surmise that he did have some technological talent and ability, certainly considerable ambition, and perhaps a touch of vision.

But Whitney by no means invented the cotton gin. Ginning prepares cotton for spinning into yarn by separating the seeds from cotton fibers. Devices for carrying out this process, called gins, have existed since at least the early common era and were widely used in India and China throughout the period we today call the Middle Ages. These cotton gins used two rollers to squeeze the seed out of the cotton fiber.

From India, the roller cotton gin traveled to the Americas, where it was used by early English colonists in Virginia and other parts of mainland British North America as they searched for a profitable export crop. In the 1700s, British inventors and manufacturers successively mechanized every aspect of yarn and textile production, dramatically raising manufacturing capacity. This vastly increased commercial demand for raw cotton.

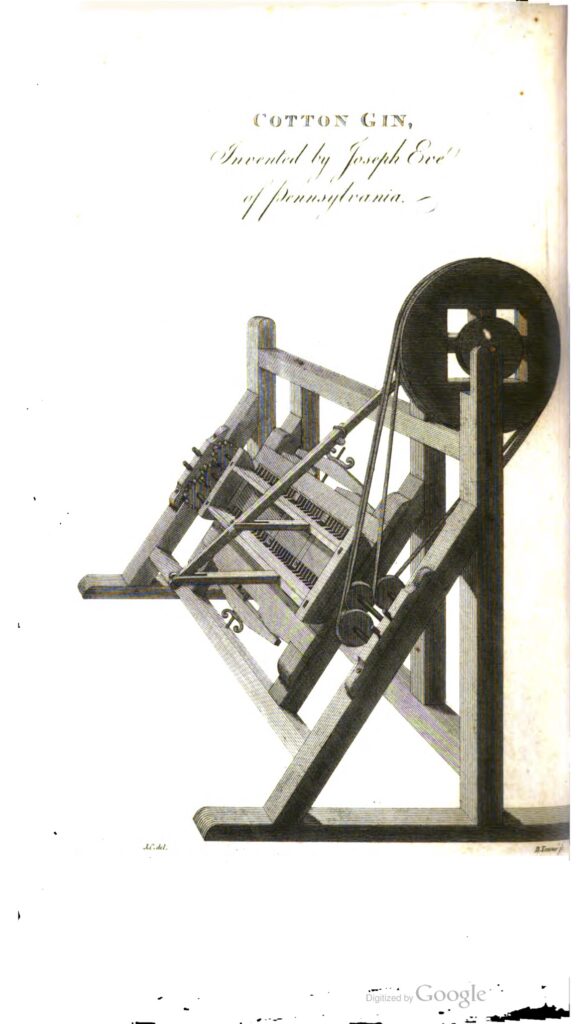

In response, roller gins were enlarged and improved. For instance, barrel gins included multiple rollers on one machine and could be powered by animals, water wheels, and windmills. These improvements, however, did not have much effect on labor productivity because they could not automate the process of feeding cotton into the gin. It was still necessary to have a different person for each set of rollers. Other improvements did increase productivity but not dramatically. For example, hand cranks for turning the rollers were replaced by treadles equipped with flywheels. These kinds of roller gins required strong men to operate and could cause serious injury if worked too strenuously for too long. In 1788, several years before Whitney came along, a Philadelphia-born inventor named Joseph Eve designed a new kind of roller gin that included an automatic feeder, for the first time promising significant productivity gains. It was complicated and “notoriously finicky,” but it worked.

The existence of these roller gins, and the rise of cotton production first in the Caribbean and then in the South, indicates that one key part of the Whitney legend is certainly untrue: there was no absolute bottleneck of production in the separation of cotton fibers from the seed. The bottleneck in part depends on the distinction between long-staple and short-staple, or green-seed, cotton. Long-staple cotton has a smooth seed that separates easily from the fiber, but it can only be grown in limited environments along the Carolina coastline. By contrast, short-staple cotton has a fuzzy seed that clings tenaciously to the lint fiber, but it can be grown throughout a much larger swath of the US South. According to the common view, only Whitney’s invention could effectively gin short-staple cotton. But this is untrue. By 1802, long before Whitney’s new machine had time to make a significant impact, the United States had become Britain’s largest supplier of cotton. Indeed, Joseph Eve relocated to Charleston, South Carolina, around this time and found success marketing his automated roller gins to farmers in the area, some of whom used it on short-staple cotton. The key point to remember here is that demand from Britain’s mechanized textile manufacturers drove the expansion of the Cotton Kingdom far more than any specific way of ginning.

Nevertheless, if Whitney did not invent the cotton gin, he did invent a cotton gin, one that worked very differently from its predecessors and had a much higher rate of output. That is, Whitney’s device produced more seeded cotton per worker per day, a significant achievement. How did it work? Roller gins squeeze cotton between two rollers, leaving a narrow space between, just wide enough for the soft fiber to pass through but not the seed. The seeds are pinched off and fall on the side where the cotton is fed in while the ginned cotton is pulled through and collected on the other side. Whitney did something else entirely. He hammered parallel rows of wire teeth around a wooden cylinder. The teeth pulled raw cotton out of a hopper toward a metal plate, called a breastwork, in which Whitney cut slits, or narrow openings for the rotating wire-teeth to pass through. As the teeth pulled the cotton through the slits, the seeds were shorn off. On the other side of the plate, the cotton was then detached from the teeth by a rotating brush. The advantage of this method was that it increased the productivity of a single worker by multitudes. In his 1793 petition for a patent, Whitney estimated that his gin raised labor productivity by a factor of fifty. This was an exaggeration, but if the true figure was a half or a quarter or even a tenth as much, it would have been significant.

Others rushed to copy Whitney’s innovation. However, there was a problem. Cotton merchants and manufacturers began to complain about the quality of the ginned cotton that Whitney’s design turned out. The Whitney gin tended to tear the fibers rather than preserving their length, as the roller gin did. This made the cotton harder to spin into yarn. As a result, roller gins continued to be produced and were widely used well into the 1820s and even later. Roller gin designs were also improved further to close the productivity gap with Whitney’s. This is another indication that the Whitney gin, though a definite technological advancement, was not the world-historical force it is typically presented to be.

Still, the higher productivity of the Whitney gin could not be ignored. Manufacturers learned to deal with the shorter fiber staples it produced and other gin makers improved its design. A key improvement was to substitute circular saws around an axel for Whitney’s wire-teeth hammered into a wooden cylinder. This made the teeth more durable. It also allowed for flexible positioning and easy replacement by using spacers in between the saw blades. The saw principle led to a lengthy patent suit that Whitney and Miller ultimately won on somewhat dubious grounds. By that time, however, Whitney was deeply in debt and despondent about ever profiting from the gin, and he had already returned North and shifted his attention to manufacturing muskets for the US Army.

It was in the patent suit that much of the Whitney legend was born. To negate the saw tooth design patent that another gin maker had received, Miller argued that Whitney had already included that idea in his original patent filing. (The inclusion was said to be implicit, because Whitney did not, in fact, mention it at all.) To generate sympathy for Whitney, Miller argued publicly and in court that had it not been for Whitney’s invention, cotton could never have succeeded in much of the South. In other words, Miller presented Whitney as the savior of a declining southern economy, who was pressing his suit only to recover a measure of the recompense he so plainly deserved. The judge largely bought this reasoning and repeated it in his decision. He thereby established the part of the legend by which Whitney’s gin rescued the South from economic stagnation and breathed new life into slavery.

Yet as we have seen, ginning was not a critical barrier to cotton production and improved roller gin designs continued in use for decades after Whitney came along. Moreover, Whitney himself was ultimately only one of many gin makers who improved the gin’s performance. We—meaning people generally in the modern world, but Americans in particular—tend to focus on lone inventor geniuses. But this is rarely how significant innovation actually happens. The case of interchangeable parts shows this even more clearly, so let’s turn our attention to that facet of the Whitney legend.

What Actually Happened, Part 2: Interchangeable Parts

Facing bankruptcy and desperate for credit, Whitney used his elite connections and the fame he had won from his gin design and patent suit, to secure a government contract to manufacture 10,000 muskets in two years. There is no evidence for the story of the reassembled guns that supposedly astonished government officials. Instead, Whitney’s need for money fortuitously coincided with the federal government’s need to appear to be doing something about the possibility of war with France. What better way to seem to be preparing than to make a deal with America’s most famous inventor? The federal government agreed to fund the construction of Whitney’s factory, which was to include advanced machinery that would supersede the need for craft skill.

Whitney ultimately produced the 10,000 guns, but it took him eight years and reams of excuses to do so. He never achieved anything like interchangeability in his lifetime. He did stick with the gun-making business and gradually improved his factory’s performance, which was further improved and modernized by his son in subsequent years. Evidence from Whitney’s factory shows that his gun pieces remained too variable for true interchangeability. Moreover, most of the work was done by hand filing rather than machine milling. During Whitney’s lifetime, the most important approach to machine-based mass production of interchangeable parts was happening in the federal government’s armory at Harper’s Ferry, in what was then still Virginia, under the direction of John Hall.

But Virginia’s slavery inhibited the full development of Hall’s innovations, and the techniques were increasingly perfected, instead, at the armory in Springfield, Massachusetts. This is not to say that the slave South hewed to a premodern or precapitalist mindset that devalued technological novelty. Not long after Whitney’s time, Cyrus McCormick, a Virginian, developed the mechanical reaper, undoubtedly one of the nineteenth century’s most important technologies. But slavery nevertheless weakened southern innovation in countless ways. It denied enslaved people education, including technical education, and any incentive to invent—circumstances that showed up in the South’s much lower per-capita patenting rates compared to the North. It denied enslaved people income, shrinking the domestic consumer markets that drove northern mass production. It was a factor in the South’s lack of cities, where aspiring technologists found one another and the financing to develop their ideas. It is telling that McCormick located his first major factory in Chicago. Similarly, in Springfield, Massachusetts, a whole ecosystem of skilled workers and specialized firms grew up around army contracting, eventually pushing decisively on the technological frontier. By the 1840s, parts were being made sufficiently uniform for interchangeability, though even then, much of the work was done by hand filing to finish the pieces to gauge.

Unlike with the cotton gin, when it comes to interchangeable parts Whitney has little claim to have contributed much. The idea itself was certainly not new with Whitney and many Americans, particularly in small arms manufacture, were experimenting with it. It would be wrong to associate success with one person. For starters, consider all the people who developed the various devices—the lathes, boring machines, milling machines, and so on—that standardized and shortened the work of turning out rough cuts of each part. And consider all the firms that made those machines. In addition, the continuing importance of very fine hand filing meant that many anonymous skilled artisans gradually developed ever-better handicraft techniques. These skills were passed on from workman to workman and remained crucial all the way through the end of the nineteenth century.

When we recognize that interchangeability was not achieved in any real way until the 1850s, and then only in small arms manufacture, we can better appreciate that the North, on the eve of the Civil War, was no industrial giant. The majority of northerners remained rural people, either farmers and their families or folks closely connected to the agricultural economy, such as agricultural commodity merchants or local blacksmiths, whose stock in trade was building and repairing agricultural implements.

This is the final nail in the Whitney legend, insofar as the legend is meant to explain the causes of the Civil War. When it comes to the outcomes of the Civil War—that is, who won the war and how—the North’s industrial lead relative to the South was indeed very significant. But when it comes to causes, the case is different, because the voters who put Lincoln in office were largely farmers and smalltown businesspeople. They were as much agricultural as the slaveholders.

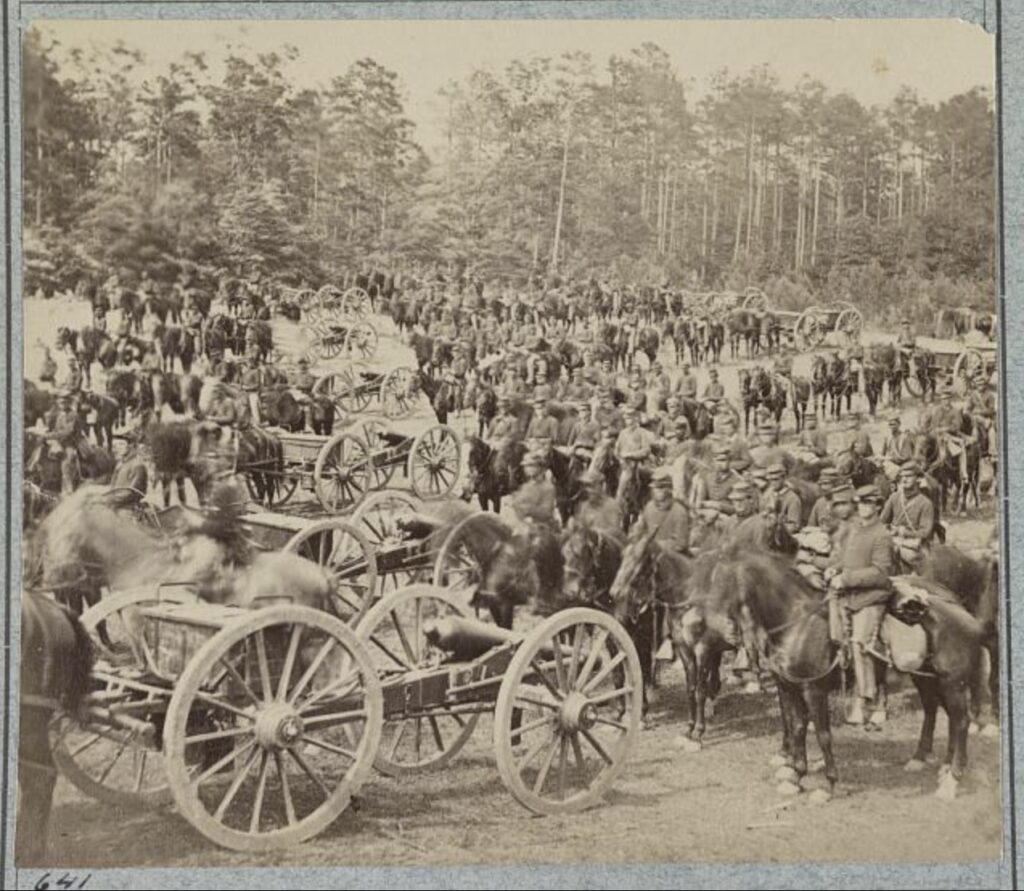

Even when it comes to the war itself, the Union’s industrial advantage can be easily exaggerated. The Union’s real strength was in logistics. Confederates actually did alright with the procurement of small arms and ordinance. They struggled much more in moving supplies to the right places. Railroads and shipping were one part of the Union advantage. But so was a less celebrated aspect of wartime supply and logistics: hay.

The Civil War was as much a war of horses as of people—perhaps more so. According to the most considered estimate, at least 3,000,000 equines (horses and mules) were required by the combined Civil War armies, and the true number “would probably exceed the estimated 3,213,363 soldiers who served.” These horses ate enormous quantities of food. Whereas standard ration for men was three pounds, for horses it was twenty-six, and for mules twenty-three.

Consider, then, William Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign, which set the stage for his famous March to the Sea. Sherman began with about 100,000 soldiers and 30,000 equines. Unlike in his rampage across Georgia, the terrain, timing, and ravaged state of the route from Chattanooga to Atlanta would not allow for “living off the land.” Consequently, almost everything had to be transported along a perilous route that wound its way 350 miles back through Tennessee and into Kentucky. Simple arithmetic will show that what must have most taxed this route was forage for the equines: 100,000 men x 3 lbs. = 300,000 lbs., and 30,000 horses x 23.5 lbs. (the average of the horse and mule ration) = 705,000 lbs. The ratio of equine to human food gets bigger still when calculated by volume rather than weight, because hay was anywhere from 2.5 to 5 times the bulk of grains.

This indicates that much of the war was actually about procuring, loading, transporting, unloading, reloading and again transporting large bales of hay, an effort that reached deep into the remotest corners of the rural North. At 200-400 pounds per bale, it required considerable scarce labor. As Union armies penetrated deeper into the South, those labor requirements increased in key forward depots. This was one reason why so-called “contrabands”—formerly enslaved people who had liberated themselves by fleeing to Union lines—proved so crucial to the war’s outcome. Without their labor, it would have been exceedingly difficult to keep the horses alive on which Union army mobility depended. All of this is simply to underscore that the North’s greater industrial capacity than the South, while certainly important, was far from the lone determining factor in the Civil War’s outcome.

To return to Eli Whitney, then, it is fair to say that he did invent a useful device—his innovative cotton gin—which became closely associated with the brutal expansion of slavery and cotton cultivation in the antebellum South. It is also fair to say that he understood the importance of interchangeable parts and participated—along with many others and without any notable success—in the attempt to achieve effective interchangeability. But he ultimately played a small role in the technological, economic, and political developments that came to define the sectional conflict. If he can hardly be blamed for starting the Civil War, he most certainly cannot be credited with winning it.

Further Reading:

For the Whitney legend, see his National Inventors Hall of Fame entry, or the recent National Constitution Center’s blog post of March 14, 2024, “The cotton gin: A game-changing social and economic invention.” The Whitney legend is so prevalent that ChatGPT replied to the prompt, “Tell me about Eli Whitney,” by stating that he “revolutionized the cotton industry” and “played a major role” in the development of interchangeable parts. The history of the cotton gin and Whitney’s role in its development is thoroughly investigated in Angela Lakwete, Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003). For Whitney and interchangeable parts, see especially Robert S. Woodbury, “The Legend of Eli Whitney and Interchangeable Parts,” Technology and Culture 1 (Summer 1960): 235–53 and Robert B. Gordon, “Who Turned the Mechanical Ideal into Mechanical Reality?” Technology and Culture 29 (October 1988): 744–78. The estimate for horses and mules in the Civil is from Gene C. Armistead, Horses and Mules in the Civil War: A Complete History with a Roster of More Than 700 War Horses (McFarland, 2013). The stuff about hay comes from my own research, some of which has been published as Ariel Ron, “When Hay Was King: Energy History and Economic Nationalism in the Nineteenth-Century United States,” The American Historical Review 128 (March 2023): 177–213. There is a lot to be said about how slavery affected southern technological innovation—much more than can be cited here—but a key perspective to be kept in mind is comparative: not whether there was any technological innovation in the South, but how much and what kind compared to other places. For a start, see the essays by Daniel Rood and John Majewski in Slavery’s Capitalism: A New History of American Economic Development, ed. Sven Beckert and Seth Rockman (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

This article originally appeared in October 2025.

Ariel Ron is the Glenn M. Linden Associate Professor of the U.S. Civil War Era and Director of the Clements Center for Southwest Studies at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. He is the author of Grassroots Leviathan: Agricultural Reform and the Rural North in the Slaveholding Republic and various other writings.