Long before wide-eyed American students left the cocoon of their colleges in search of adventures abroad, nineteenth-century American Protestant missionaries had set sail for parts unknown with a similar sense of excitement and trepidation. These were twentysomething men and women, often newly married and newly minted from New England seminaries, who had not chosen their destinations. Instead, they faithfully heeded the call of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) and were dispatched wherever this missionary organization deemed they were the most needed to bring its grand plan for moral reform to fruition.

Loosening the Tongue: Language Learning among Early American Missionaries to the Ottoman Empire

Especially in the early years, with no grammar books or dictionaries of spoken languages, missionaries relied heavily on their cultural know-how and linguistic expertise and came to learn about the nuances of Armenian culture through them.

In the first decades after its founding in 1810, the ABCFM established mission stations close to home—among the Cherokee in Tennessee, for instance—but more often across oceans and continents, where missionaries encountered entirely new cultures and ways of life. While dreams of religious revival rather than rollicking revelry were what led them to abandon their comfortable lives in the United States, they did share one pressing concern with today’s study abroad students: learning the languages of their host cultures.

This is the story of the linguistic trials and travails of the first band of American missionaries sent to evangelize the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire in the 1830s and 1840s. Seemingly unlikely targets, Armenians had adopted Christianity beginning in the fourth century and had their own ecclesiastically independent church. From the missionaries’ perspective, however, they were nothing more than “nominal” Christians who had strayed from biblical teachings and needed a new dose of spiritual enlightenment.

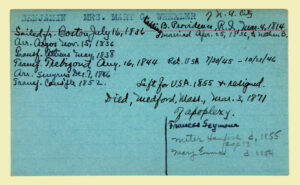

While the number of American missionaries who worked among Armenians in various corners of the Empire would swell later in the century, their numbers were much humbler at the start. With less word-of-mouth knowledge and fewer language-learning resources, the linguistic challenges they faced were also much more palpable. Yet in no time, not only were these young men and women from South Carolina, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and across New England teaching and preaching in local languages, but they were also supervising translations into them and, in the case of one particularly industrious missionary, codifying them in grammars and dictionaries.

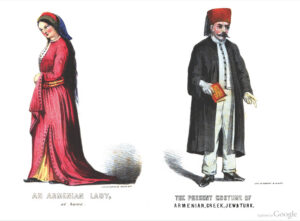

Male missionaries arrived in the mission field well versed in Greek, Latin, and Hebrew from their seminary days. But Armenian was a terra incognita for male and female missionaries alike, who embarked for the Ottoman Empire with little to no knowledge of the language. With its own distinct alphabet, a set of commonly used guttural sounds and few cognates with English, Armenian contained an array of unique stumbling blocks for them.

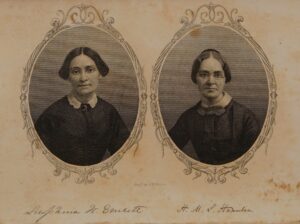

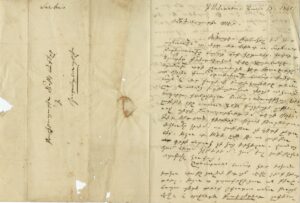

Nevertheless, many jumped into the study of Armenian with both feet. For example, Massachusetts-born Seraphina Everett initially devoted herself to studying Armenian for five hours each morning. She practiced by writing letters in her newly acquired tongue to her friend and fellow missionary Harriet Hamlin and by reading Armenian translations of The Pilgrim’s Progress and Robinson Crusoe. “Our great anxiety is to have our tongues loosed, and we are willing to toil for it,” Seraphina wrote to Harriet in 1845, the year both women arrived in the mission field at age twenty-two and twenty-five, respectively.

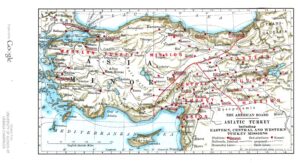

Upon stepping off the ship in Constantinople (Istanbul) or Smyrna (Izmir), however, the missionaries quickly realized that the linguistic landscape was far more complicated than they had imagined. First, there were different kinds of Armenian to master. In addition to sometimes mutually unintelligible spoken forms that varied by region, there was also a classical variety used only in writing. Imbued with prestige, this classical form was the main language of print at the time as well as the main language of religious texts and rituals.

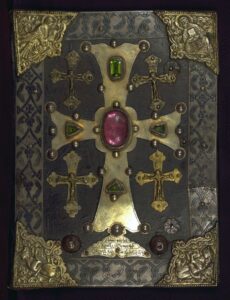

Second, much to their surprise, many Armenians did not, in fact, know any Armenian. Missionaries consistently expressed shock that even those who spoke regional forms of Armenian had little grasp of the classical language and thus could not understand the liturgy of the Armenian Church or the fifth-century Armenian translation of the Bible. When Massachusetts-born William Goodell first arrived in the Ottoman Empire, for example, he noted with dismay that the Armenians he met were much more apt to kiss religious books and to admire their bejeweled covers or gilded pages than to read them.

Beyond a widespread unfamiliarity with the classical language, some Armenians had no knowledge of modern forms of Armenian either and instead used Turkish or Kurdish in their everyday lives. This meant that to spread their message, those stationed in these communities needed to set about acquiring these languages too. As the ABCFM leadership in Boston expected them to get down to business preaching, teaching, writing and translating as soon as possible, learning the local languages quickly and starting to publish in them was of the essence.

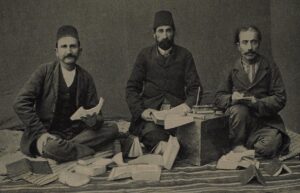

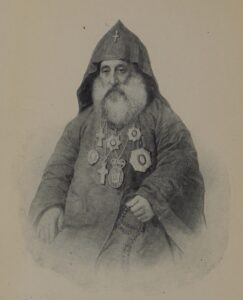

How did these Americans on foreign shores manage to navigate such linguistic diversity? How did they gain such a firm grip on these languages that they were able to convincingly convey abstract religious concepts in them? Here the missionaries were indebted to a small coterie of Armenians who were curious about, if not sympathetic to, their mission and message. Especially in the early years, with no grammar books or dictionaries of spoken languages, missionaries relied heavily on their cultural know-how and linguistic expertise and came to learn about the nuances of Armenian culture through them. This coterie included some of the most learned Armenians of the day who, while shepherding the missionaries into an Armenian social sphere, concurrently held positions as teachers, school principals, writers, and newspaper editors.

Often in exchange for English lessons, these Armenian intellectuals began by tutoring the missionaries in Armenian and Turkish, sometimes within days of their arrival. They were their language teachers, their interpreters, their cultural conduits. In a word, they were their voices in a new land. In the process, many became advisors, close collaborators and friends, living with the missionaries and their children and breaking bread with them. The South Carolina-born missionary John B. Adger, in particular, wrote with effusive affection and respect for his right-hand man, Sarkis Hohannisian, deferring to his expertise, including his news in letters back home to Charleston, and keeping vigil at his bedside in his final hours. Such warm, symbiotic relationships contrast sharply with the caste-like system imposed by later waves of American missionaries.

These “native assistants,” as they were called, were taking a considerable risk in associating with the missionaries. Armenian church leaders saw the missionaries as poachers among their flock and accused all who rubbed elbows with them of heresy, threatening them with excommunication, exile, social ostracization, and property confiscation. In their lifetimes and beyond, when these figures have been discussed in Armenian sources, there is rarely any mention of their intellectual labor for the mission, as if to avoid besmirching their reputation as Armenian patriots. These teachers, translators and interpreters were driven to do this work for a whole host of reasons: some were genuinely drawn to the missionaries’ alternative approach to Christianity; others thought their work could elevate Armenians spiritually and prompt reform within the Armenian Church; and others still were just looking for a way to make extra money.

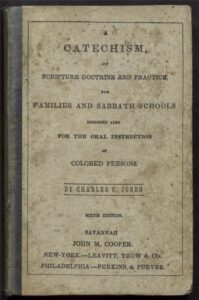

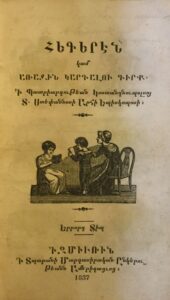

The most skilled among them were hired to work closely with the missionaries in the preparation of more than one hundred translations. Given the fierce resistance to their schools and oral preaching, publications were thought of as a way to introduce Armenians to Protestant ideas under the radar, entering homes and communities more easily and covertly than any missionary could. These books ranged from massive religious tomes to school textbooks to moralizing tales by the American Tract Society. In the first decades of the mission, these materials were published by an independent missionary press in Malta—and later in Smyrna—that used Armenian letters cast in Brooklyn, among other locales.

Preparing a translation was a long, painstaking, and collaborative process with a clear division of labor. First the missionary selected the text in consultation with the ABCFM and/or with fellow missionaries, at times abridging and adapting it for an Armenian readership. Then the Armenian translator prepared a first draft, careful to be as clear and idiomatic as possible so as not to alert readers to the text’s “foreignness.” This draft was thoroughly examined by the missionary, who considered whether all meanings had been accurately conveyed. In some cases, the missionary relied on his (never her) training in biblical languages and reviewed the translation against the Greek or Hebrew originals. If there was a discrepancy, the passage was marked for discussion. The missionary and translator then went through the entire text together, comparing the translation to the source text line by line and making revisions along the way. The missionary deferred to the translator and to the other Armenians he consulted in all matters of style and usage, relying on their knowledge of Armenian written norms and conventions. After multiple rounds of edits, the translation was typeset and the missionary reviewed the proofs, reading for errors in a language that he had sometimes only just begun to learn a few years earlier. Many reported that this exacting and laborious work took a tremendous toll on their eyes.

Missionaries responded to the linguistic diversity among Ottoman Armenians by publishing in a range of languages. They often specialized in preparing translations in either Armenian or Armeno-Turkish, the Turkish language written using the Armenian alphabet. Later in the century, a handful of books were also rendered into Armeno-Kurdish, the Kurdish language written using the Armenian alphabet. The key to accessing all of these publications was the alphabet primer, which numbered among the missionary press’s most popular books. Instilling the desire to learn to read—which was not at all widespread among Armenians at the time—was one of the missionaries’ primary objectives. This push was the first step in their evangelizing mission. For them, learning to read was crucial, because it would give Armenians the ability to interpret religious texts for themselves and to enter into a more direct relationship with the divine, without the mediation of the Armenian priest.

To this end, the missionaries also published their materials in vernacular rather than classical forms. In describing the linguistic status quo among Armenians in the 1830s to Sunday school children in his native Pennsylvania, missionary Benjamin Schneider tried to explain the need for vernacular materials in terms they could understand: “What would you think if your ministers should preach and pray in Latin? And how much would you learn, if your teachers should undertake to instruct you from the Bible in Greek or Hebrew? I think you would not long go to the Sunday-school.” Books composed in vernacular Armenian were so rare in the early years of the mission that some Armenians, especially those who disapproved of using anything but the classical variety in print, began to refer to it as the “language of the Protestant,” acting as if the missionaries had brought this form of the language with them from the United States.

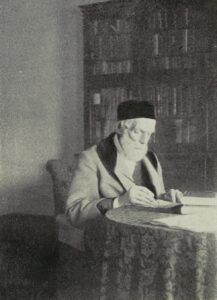

Missionaries often began teaching Armenians to read in the Armenian alphabet shortly after learning how to do it themselves. This was especially common among female missionaries, who promoted literacy among girls and women and organized lessons in their homes in the years before mission schools were established. The early missionaries who managed to become literate and conversant in local languages also did their best to help their successors quickly acquire these skills. No missionary did more in this regard than New Jersey-born Elias Riggs, who was said to have picked up languages as effortlessly as most people pick up a tune. To help new waves of missionaries find their linguistic bearings in the mission field, he composed a grammar of vernacular Armenian (1847), a dictionary of vernacular Armenian (1847), and a grammar of Armeno-Turkish (1856), all with English explanations. In addition to having been critical resources for new missionaries in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, these books are also vital for researchers in Armenian studies today, who are indebted to Riggs for having documented some of the ways mid-century Armenians spoke.

Whether they returned home to the United States after only a few years or lived out their lives in the Ottoman Empire, these nineteenth-century American missionaries were rooted in Armenian communities for the extent of their time with the ABCFM. This rootedness was deepened by their facility with the languages of these communities, ones that they had spent years working to master. The process of acquiring these languages and of publishing in them underscores the degree to which these missionaries were reliant on the sympathies and skills of those they had come to convert, complicating the expected power dynamic and revealing the indispensable intellectual labor of Armenians within the early American mission.

Further Reading

John B. Adger, My Life and Times (Richmond: Presbyterian Committee of Publication, 1899).

Emily Conroy-Krutz, Christian Imperialism: Converting the World in the Early American Republic (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015).

Mary Gladding Benjamin, The Missionary Sisters: A Memorial of Mrs. Seraphina Haynes Everett and Mrs. Harriet Martha Hamlin (Boston: American Tract Society, 1860).

William Goodell, The Old and the New; or The Changes of Thirty Years in the East, with Some Allusions to Oriental Customs as Elucidating Scripture (New York: M.W. Dodd Publisher, 1853).

Cyrus Hamlin, My Life and Times (Boston: Congregational Sunday School and Publishing Society, 1893).

H.G.O. Dwight, Christianity in Turkey: A Narrative of the Protestant Reformation in the Armenian Church (London: James Nisbet and Co., 1854).

Elias Riggs, Reminiscences for My Children by Elias Riggs, Missionary of the A.B.C.F.M in Greece and Turkey (n.p., 1891).

Benjamin Schneider, Letters from Asia Minor, Respecting the Greeks and Armenians. (Philadelphia: American Sunday-School Union, 1837).

Eli Smith, Researches of the Rev. E. Smith and Rev. H.G.O. Dwight in Armenia: Including a Journey through Asia Minor, and into Georgia and Persia, with a Visit to the Nestorian and Chaldean Christians of Oormiah and Salmas (Boston: Crocker and Brewster, 1833).

This article originally appeared in October 2022.

Jennifer Manoukian is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her research explores the social and intellectual history of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire.