Mark Twain was obsessed with zombies. Huck Finn’s adventures in the antebellum South, for example, can be traced in part to Pap’s lurid nightmare about what my students recognize as zombies: “Tramp—tramp—tramp; that’s the dead; tramp—tramp—tramp; they’re coming after me; but I won’t go. Oh, they’re here! don’t touch me—don’t! hands off—they’re cold; let go. Oh, let a poor devil alone!” In violation of his own rule “that the personages in a tale shall be alive, except in the case of corpses, and that always the reader shall be able to tell the corpses from the others,” Twain’s writings are shot through with ghosts, skeletons, resurrected cadavers, and the walking dead. We know Twain as an author who dealt with great themes: childhood, innocence, slavery, freedom, conscience. But all these themes are entangled with his fascination with reanimated corpses—a fascination that has much to teach us about our own preoccupation with zombies. Like The Walking Dead and other 21st-century zombie plots, Twain’s writings bring the dead to life in order to meditate on the social and economic circumstances that produce hungry, ragged, and diseased masses. In Twain’s corpus, divergent iterations of the walking dead dramatize how unevenly cultural prestige and human rights are distributed across the lines of class, race, and nation.

Dead celebrities

As an irreverent realist and a regionalist author invested in tall tales and vernacular speech, Twain found his fellow Americans’ admiration of dead authorities absurd. In early hoaxes published in the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise, Twain satirized the popular fascination with dead bodies by describing a recently exhumed petrified body thumbing its nose at spectators and a man riding into Carson City “with his throat cut from ear to ear.” In his account of his travels in Europe, The Innocents Abroad (1869), Twain describes a trick that he and his travel companions frequently played on their European tour guides:

There is one remark (already mentioned) which never yet has failed to disgust these guides. We use it always, when we can think of nothing else to say. After they have exhausted their enthusiasm pointing out to us and praising the beauties of some ancient bronze image or broken-legged statue, we look at it stupidly and in silence for five, ten, fifteen minutes—as long as we can hold out, in fact—and then ask:

“Is—is he dead?”

According to this joke, the grandeur and accomplishments of historical personages such as Michelangelo and Christopher Columbus count as nothing next to the prestige of death. For Twain—who famously contrasts the ruined landscapes of the Old World with the natural sublimity of Lake Tahoe and Niagara Falls—the Grand Tour of Europe maintains artificial notions of greatness and hierarchy through the ritual adulation of long-dead authorities.

Even the child protagonist of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) is acutely aware of the reverence accorded to the dead. Feeling wrongfully punished and emotionally neglected by Aunt Polly, Tom fantasizes about dying: “And he pictured himself brought home from the river, dead, with his curls all wet, and his sore heart at rest. How she would throw herself upon him, and how her tears would fall like rain, and her lips pray God to give her back her boy and she would never, never abuse him any more!” Tom later indulges this narcissistic fascination with his own death by orchestrating his resurrection at his own funeral after he learns that he and his friends are presumed drowned. Along the way, Tom learns that Aunt Polly and others perceive the boys differently when they believe the boys are dead: instead of scolding and beating him, Polly remembers Tom as “the best hearted boy that ever was!” Later, when Tom and Becky are nearly given up for dead when they lose their way in McDougal’s Cave, their emergence leads to universal celebration: “it was the greatest night the town had ever seen.” Like the historical figures represented in European paintings and sculptures, Tom’s presumed deaths and reincarnations impart an ennobling aura.

Twain’s recently republished play, Is He Dead? (2003, written in 1898), further develops Tom Sawyer’s fantasy of being present at his own funeral. The comic plot is fueled by “This law: that the merit of every great unknown and neglected artist must and will be recognized, and his pictures climb to high prices after his death.” Hounded by poverty and debt, the painter Jean-Francois Millet decides to capitalize on this economic law during his own lifetime by faking his own death. This vastly increases the value of his paintings and saves Millet and his friends from their debtors. At the painter’s funeral, Millet’s scheme nearly fails when the king insists on viewing the body; however, the coffin has been filled with Limburger cheese as a precaution, and the rankness that overcomes the funeral guests when the coffin is unsealed dissuades them from looking. In Is He Dead? value emerges from the reputation of death: being presumed dead saves Millet from poverty, eviction, and debtor’s prison. Even more than it does for Tom Sawyer and the European celebrities of The Innocents Abroad, death turns everything around for Millet: it offers him new life possibilities. The following section will turn to stories concerned not with the celebrity status that death can impart upon one’s name, but with the body in the coffin.

Medical cadavers

Twain explored a darker instance of the reanimated dead in his treatments of “resurrectionists” who dug up fresh cadavers and sold them to medical researchers. The medical cadaver is in many ways the antithesis of the dead celebrity: its value derives not from its name and prestige but from its commodification as an anonymous object. Together, the dead celebrity and medical cadaver raise questions about whose deaths are memorialized, and whose deaths are ungrieved, forgotten, or commodified. Although they occur in novels focused upon Southern white boys, Twain’s references to medical cadavers significantly occur in scenes that highlight Tom and Huck’s encounters with racial difference.

In Tom Sawyer, Injun Joe’s first and last appearances occur in proximity to medical cadavers. Tom and Huck first encounter him in the cemetery, where he and Muff Potter have lured Doctor Robinson on the pretext of digging up a recently deceased corpse for medical experimentation. Injun Joe’s true purpose, however, is revenge: “Five years ago you drove me away from your father’s kitchen one night, when I come to ask for something to eat, and you said I warn’t there for any good; and when I swore I’d get even with you if it took a hundred years, your father had me jailed for a vagrant. Did you think I’d forget? The Injun blood ain’t in me for nothing. And now I’ve got you, and you got to settle, you know!” Toward the end of the novel, Tom encounters Injun Joe again when he and Becky Thatcher are lost deep in McDougal’s Cave. Injun Joe eventually dies in the cave, but his is not the only corpse that Twain—or others familiar with his childhood town of Hannibal, Missouri—would have associated with that cave.

The actual cave at the southern end of Hannibal was purchased by Dr. Joseph McDowell while Twain was a child. Twain later recalled that the cave “contained a corpse—the corpse of a young girl of fourteen. It was in a glass cylinder inclosed in a copper one which was suspended from a rail which bridged a narrow passage. The body was preserved in alcohol and it was said that loafers and rowdies used to drag it up by the hair and look at the dead face. The girl was the daughter of a St. Louis surgeon of extraordinary ability and wide celebrity. He was an eccentric man and did many strange things. He put the poor thing in that forlorn place himself.” If Injun Joe’s corpse stands in for the preserved body in McDowell’s cave, there are nevertheless stark difference between them: the former is sealed in the cave while still alive, and his body ends up hidden from sight, buried near the mouth of the cave rather than in the town cemetery. Although his funeral is well attended and his death memorialized by calling a cave feature “Injun Joe’s Cup,” this profane burial marks Injun Joe’s outcast status as a “half-breed,” a “vagrant,” and a criminal condemned to death.

In an episode excised from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), Jim tells a lewd “ghost story” about the literal reanimation of a medical cadaver. Asked by a former master (a medical student) to warm up a cadaver in preparation for a dissection, Jim goes to the dissection room around midnight and sits the cadaver on the dissecting table. When the cadaver’s eyes open, a terrified Jim covers its face with a sheet and then reaches down between its legs to fetch a candle. While Jim’s head is lowered between the cadaver’s legs, “down he comes, right a-straddle er my neck wid his cold laigs, en kicked de candle out!” Twain likely decided to excise these passages because their lewd attempts at humor and their caricature of Jim’s superstitions detract from the novel’s emphasis on Jim’s dignity.

But this expunged story about Jim’s unwilling intimacy with a medical cadaver—like Injun Joe’s proximity to them throughout Tom Sawyer—points to significant demographic factors in the sourcing of cadavers for scientific research. Nineteenth-century “resurrectionists” disproportionately targeted the corpses of socially vulnerable groups because they were less likely to be prosecuted for stealing those bodies. As Harriet Washington explains, slaves could not legally withhold consent for research or medical procedures conducted after their death. “If a master sent a sick, elderly, or otherwise-unproductive slave to the hospital, he usually gave the institution caring for and boarding the slave carte blanche for his treatment—and for his disposal.” Washington demonstrates that this targeting of black bodies persisted after Emancipation: “In 1879, five thousand cadavers a year were procured for medical use, most of them illegally, and in the South most were those of African Americans.” If biological differences were cited as justifications for racist practices during life, dead black bodies became a valuable resource for enhancing medical knowledge and health care made disproportionately available to white patients. The sourcing of medical cadavers thus maps out one way in which life and death circulated between white and nonwhite subjects in the nineteenth century.

Civil death

The racial logic behind the sourcing of medical cadavers approximates Twain’s account of tourists collecting the bones of native Hawai’ians in an early travel sketch entitled “A Battle Whose History is Forgotten.” The willful forgetting of the Hawai’ian past makes these remains ungrievable to Twain and his white travel companions, enabling them to collect and trade bones with little compunction: “I did not think it was just right to carry off any of these bones, but we did it, anyhow.” Situated beyond the scope of ethical compunction and legal protection, these desecrated bones are not only literally dead but dead in the eyes of law and society. This condition, which the legal scholar Colin Dayan calls “civil death,” illuminates Twain’s career-long pattern of conflating racialized characters with cadavers.

In his early, unfinished story “Goldsmith’s Friend Abroad Again” (1870-71), Twain depicts a Chinese immigrant named Ah Song Hi who is assaulted on the streets of San Francisco, arrested for “disturbing the peace,” beaten and called a “loafer” in jail by two Irish loafers, and convicted at a trial at which he is not permitted to testify. This narrative about the vulnerability of the Chinese in California breaks off with the remark that the newspaper reporter “would praise all the policemen indiscriminately and abuse the Chinamen and dead people.” Since neither the Chinese nor the dead people can bear witness in a California court, they have the same standing in the eyes of the court reporter.

Tom Sawyer makes numerous references to Injun Joe’s lack of legal recourse, and indeed depicts this inability to seek legal redress as the origin of his vindictive schemes. He first attacks Doctor Robinson because “your father had me jailed for a vagrant”; later, he attempts to attack and mutilate the Widow Douglass because her husband convicted him of vagrancy and had him “horsewhipped in front of the jail, like a nigger!” Injun Joe’s slow death in McDougal’s cave is also caused by a judge, who decided to prevent children from getting lost in the cave by having “its big door sheathed with boiler iron …and triple-locked.” A social outcast with a history of being arbitrarily jailed and whipped for vagrancy, Injun Joe dies in one of the few refuges available to him near town.

Injun Joe’s death has a source in “Horrible Affair,” an 1863 Virginia City Territorial Enterprise article attributed to Twain which tells of how a posse sealed a “noted desperado” in a cave, only to discover the next day “five dead Indians!—three men, one squaw, and one child, who had gone in there to sleep, perhaps, and been smothered by the foul atmosphere after the tunnel had been closed up.” As with Injun Joe, these Indians’ death by indirection results from their social vulnerability: the family was likely seeking shelter in the cave as a result of displacement, poverty, or persecution.

In Huckleberry Finn, Huck’s freedom and mobility are consistently contrasted with Jim’s immobilization. Whereas faking his own death gives Huck the freedom to experiment with new lives along the river’s shore, Jim’s movement paradoxically requires that he remain still, concealed in a swamp or cave, posing as a captured runaway, tied up on the raft, or painted blue and disguised as a “Sick Arab” who “didn’t only look like he was dead, he looked considerably more than that.” Jim looks more than dead because he is dead to the law, subject to being recaptured, punished, or sold by any white person he comes across. Twain’s most celebrated novel about a boy’s adventures is also a novel about a black man’s inability to move freely in the South, where antebellum slavery and post-Emancipation vagrancy laws both served to police black movement and capture involuntary black labor.

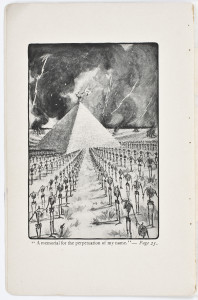

The unburied dead take on monumental proportions in King Leopold’s Soliloquy (1905), Twain’s satirical condemnation of King Leopold’s brutal rule in the Congo Free State. In Twain’s pamphlet, Leopold describes a proposed monument consisting of 15 million skulls and skeletons. The monument would consist of an enormous pyramid of skulls surrounded by “forty grand avenues of approach, each thirty-five miles long, and each fenced on both sides by skulless skeletons standing a yard and a half apart and festooned together in line by short chains stretching from wrist to wrist and attached to tried and true old handcuffs stamped with my private trade-mark, a crucifix and butcher-knife crossed, with motto, ‘By this sign we prosper.’” In his anti-imperialist writings, Twain makes a point of counting those killed by colonial governments and wars. This grotesque image of fifteen million unburied skeletons bears witness to the dead black bodies underlying Leopold’s wealth. Twain’s meticulous calculations of distances challenge readers to fathom such an immense number of corpses, while subtly pointing to connections between racist policies within the U.S. and Leopold’s colonial violence by noting that this configuration of skeletons “would stretch across America from New York to San Francisco.” By putting colonialism’s dead bodies on display, Twain’s imaginary monument gives a new meaning to his aphorism, “Only dead men can tell the truth in this world.”

Returning to Pap Finn’s nightmare about the walking dead, we can see that his terror stems from a sense of being on the verge of civil death. Pap fears being criminalized and stigmatized as an alcoholic drifter with no means of employment. Specifically, his nightmare seems to register his status as a vagrant or tramp—a criminal category that was disproportionately used to police and discipline black subjects in the post-Emancipation South. As a poor white “vagrant,” Pap risks the kinds of brutal punishment imposed on the “loafer” Ah Song Hi and the “vagrant” Injun Joe, as well as the status of civil death that characterizes so many of Twain’s black, indigenous, Chinese, Filipino, and Congolese subjects. Pap’s dream dramatizes one important reason for white Americans’ investments in Jim Crow and other racist policies: an anxious desire to differentiate between impoverished white subjects and racial “others,” to bind social status and state protections to race rather than class, to insulate whiteness from death.

Further Reading

Writings by Twain referenced in this article include “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses,” in ed. Tom Quirk, Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches (1994); “Petrified Man,” “A Bloody Massacre Near Carson,” and “Horrible Affair,” in eds. Edgar Branch, Robert Hirst, and Harriet Smith, Early Tales and Sketches, Vol. 1: 1851-1864 (1979); “Jim’s Ghost Story,” excluded manuscript passage, in ed. Stephen Railton, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (2011). Mark Twain and Medicine: “Any Mummery Will Cure” (2011) by K. Patrick Ober details Twain’s familiarity with Dr. Joseph McDowell’s cave. For important analyses of Twain’s representations of slavery and blackness, see Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992) and Eric J. Sundquist, To Wake the Nations: Race in the Making of American Literature (1993). For overviews of Twain’s treatments of race and empire, see ed. Shelley Fisher Fishkin, A Historical Guide to Mark Twain (2002). On the links between race, imperialism, and death in Twain’s writings, see Hsuan L. Hsu, Sitting in Darkness: Mark Twain’s Asia and Comparative Racialization (2015).

On social and legal manifestations of death, see Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (1982); Colin Dayan’s discussion of the “civil death” of convicted felons in the wake of emancipation in The Law is a White Dog: How Legal Rituals Make and Unmake Persons (2011); and Achille Mbem11222321be, “Necropolitics,” Public Culture 15:1 (2003). For an analysis of connections between death and nineteenth-century American conceptions of citizenship and freedom, see Russ Castronovo, Necro Citizenship: Death, Eroticism, and the Public Sphere in the Nineteenth-Century United States (2001). For a historical discussion of black medical cadavers and other instances of medical racism, see Harriet Washington, Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present (2007).

This article originally appeared in issue 16.3 (Summer, 2016).

Hsuan L. Hsu is a professor of English at the University of California, Davis, and author of Geography and the Production of Space in Nineteenth-Century American Literature (2010) and Sitting in Darkness: Mark Twain’s Asia and Comparative Racialization (2015). He is currently writing a book about olfactory aesthetics and environmental risk.