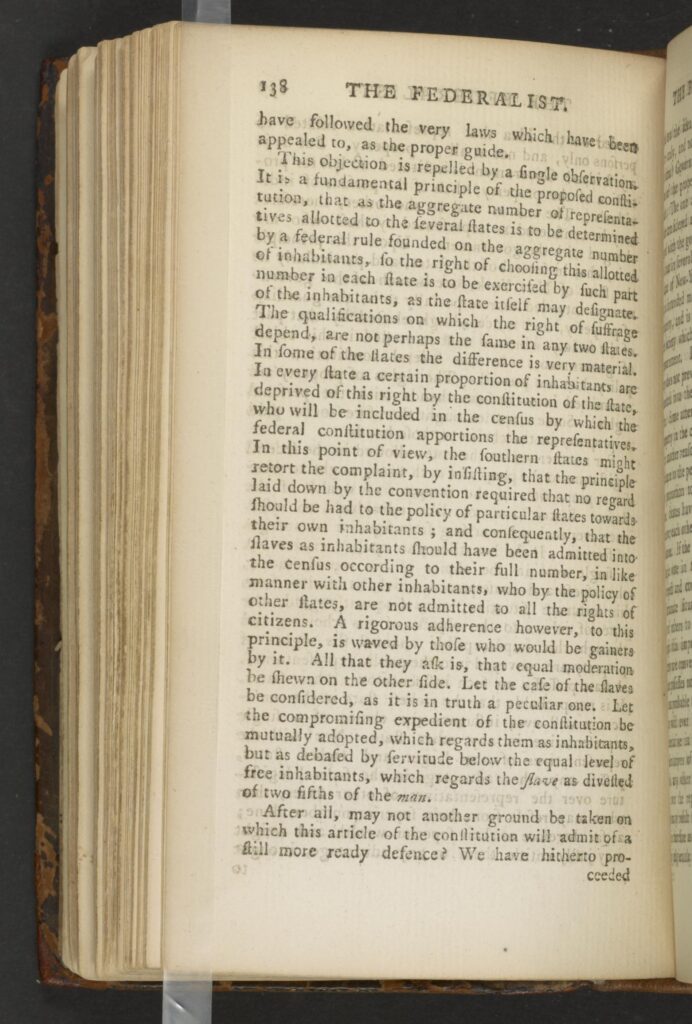

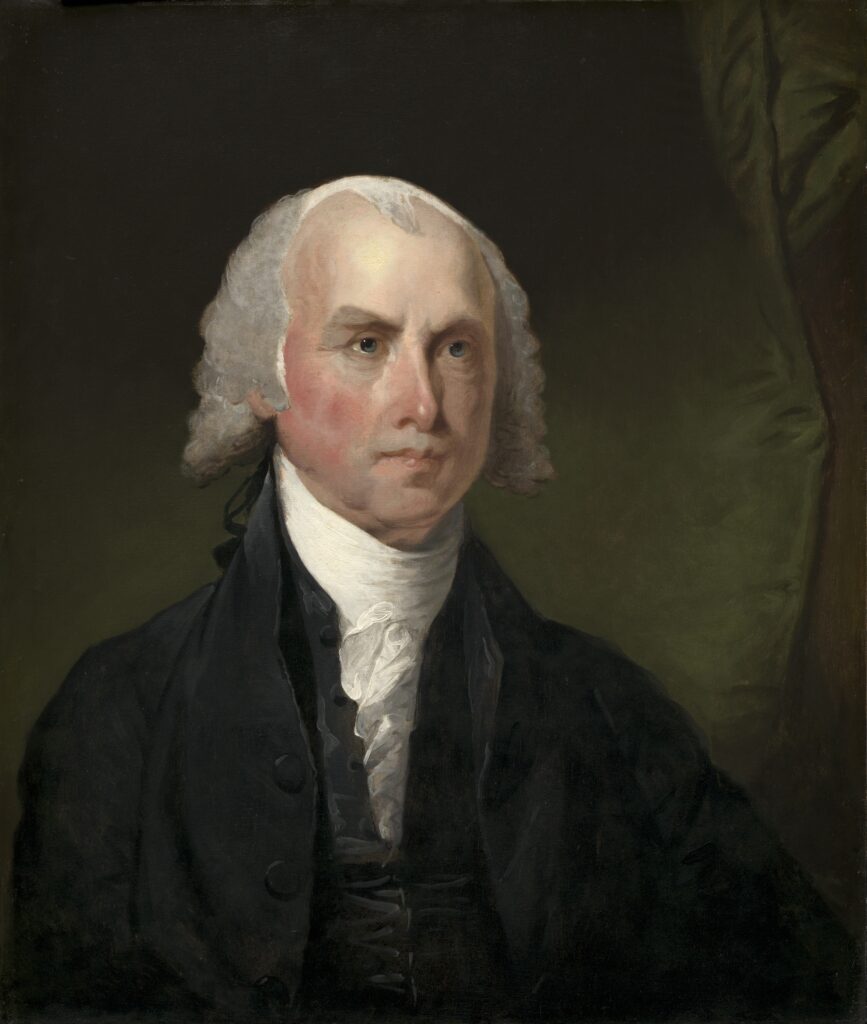

“Let the case of the slaves be considered as it is in truth a peculiar one. Let the compromising expedient of the Constitution be mutually adopted, which regards them as inhabitants, but as debased by servitude below the equal level of free inhabitants, which regards the slave as divested of two fifths of the man.” So wrote James Madison in Federalist 54.

Not “Three-Fifths of a Person”: What the Three-Fifths Clause Meant at Ratification

Denials of Black humanity, free and enslaved, coexisted with explicit acknowledgment that enslaved Black people, though legally deemed “property,” were people.

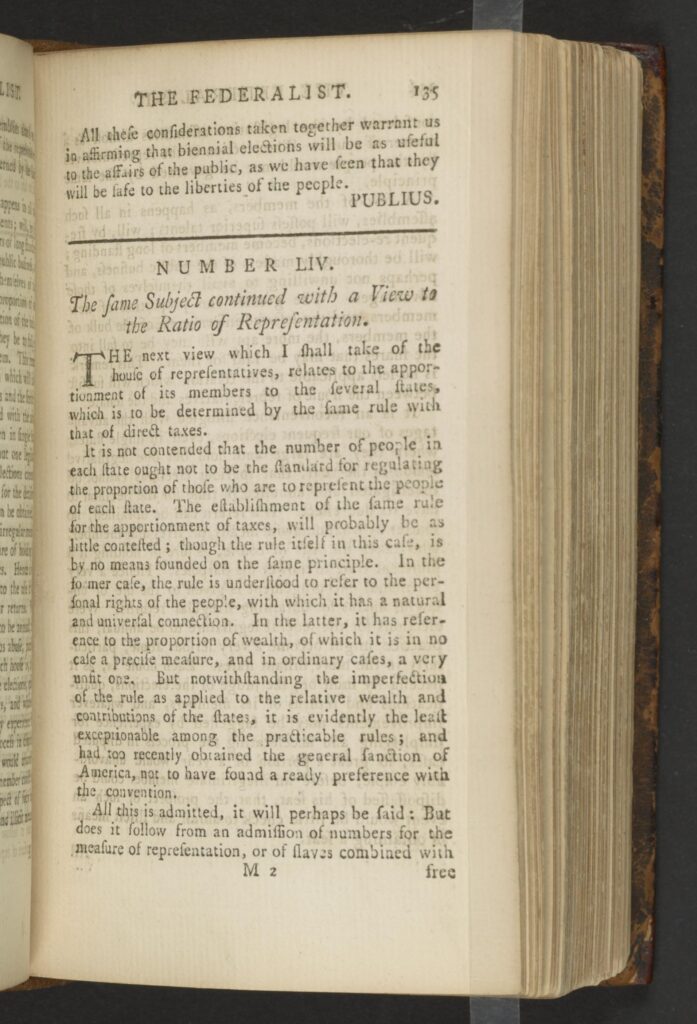

Madison was talking about the three-fifths clause of the United States Constitution. Appearing in Article I, Section 2, the clause read:

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.

At its most basic, the three-fifths clause stipulated that three-fifths of the enslaved population of a state would be counted alongside five-fifths of the free population for determining how many members in the House of Representatives each state received. Three-fifths of the enslaved population would also be subject to “direct Taxes,” should Congress impose any. But because the number of Electoral College votes would be determined by adding the number of Senators a state received (always two) to the number of House members a state was entitled to, a higher enslaved population would give a state greater influence over both the House (where all tax bills had to originate) and over the choice of president.

Madison’s phrase—divested of two fifths of the man—sounds akin to the most common way that scholars, teachers, and anyone else talking about the three-fifths clause today describes what it did: that it counted each slave as “three-fifths of a person.” This phrasing suggests a shared presumption among whites that black people were only fractionally human. There is certainly no shortage of examples of whites arguing precisely this, especially in the antebellum era. And, at first glance, that appears to be what the three-fifths clause is doing. The fraction “three fifths” is in the text itself, and though the word “slave” is never used, the clause is clearly talking about enslaved Black people. There are understandable reasons why it is so easy to assume that defenders of slavery on some level had to believe that Black people, free or enslaved, were innately not fully human.

Yet this phrasing is, at best, misleading. So far as I can tell, commentators on the three-fifths clause in 1787 and 1788—its defenders as well as its critics—did not use this phrase. Madison’s line appears to have come the closest, and even he did not mean that Black people were only sixty percent human. In fact, his argument, like that of other defenders of the three-fifths clause, rested on the assertion that enslaved Black people were three things simultaneously: subordinates to whites, legally the “property” of their owners, and human beings, through and through. Southerners like Madison had a vested interest in acknowledging that enslaved people were people, since states with large enslaved populations—Madison’s home state of Virginia most of all—would gain greater representation in the House and the Electoral College through the inclusion of three-fifths of the enslaved population.

Denials of Black humanity, free and enslaved, coexisted with explicit acknowledgment that enslaved Black people, though legally deemed “property,” were people. Either could be invoked at different moments by the Constitution’s defenders (who called themselves federalists) as well as its critics (whom federalists pejoratively labeled antifederalists) to drive home specific arguments they sought to make. But arguments that enslaved people were people, and those claiming they were “property,” did not divide cleanly along political or sectional lines. When we presume that arguments in defense of slavery and denials of full Black personhood had to go hand-in-hand, we can easily miss or minimize how important it was for those defending the Constitution’s protections for slavery to acknowledge, and at times even emphasize, the personhood of the enslaved. Closer attention to the debate over the three-fifths clause during the public ratification debate reveals how central the personhood of the enslaved was to the Constitution’s protections for slavery, and how explicit slavery’s defenders were that Southern states stood to gain by it.

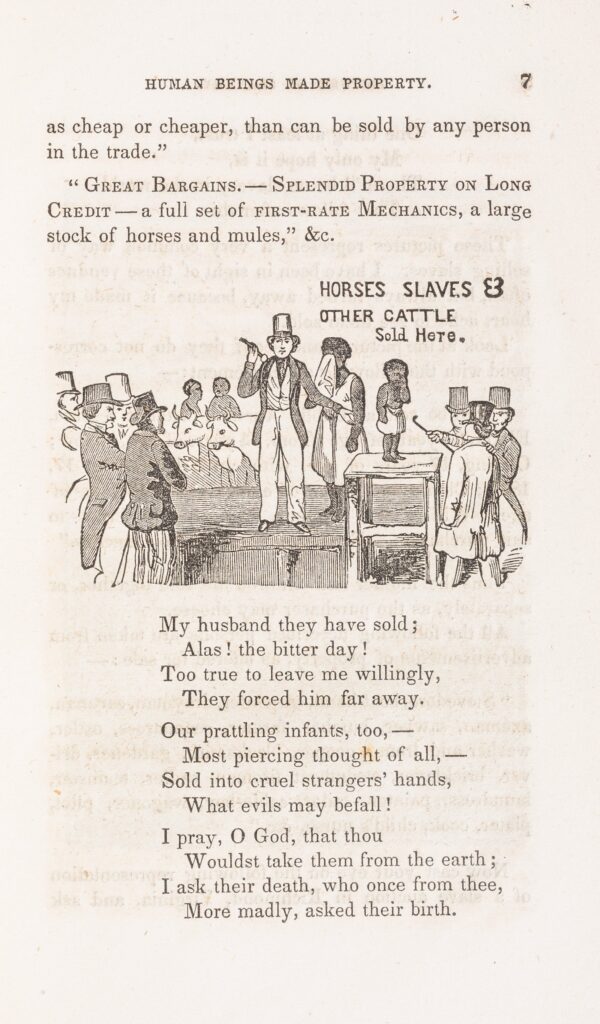

To be sure, whites North and South called the people they enslaved “property” constantly. They often used words like “Black” and “negro” as synonyms for “slave,” reflecting a tendency to equate Blackness with bondage. They frequently compared Black people to animals, especially beasts of burden. Slavery itself was brutal and, by its very nature, dehumanizing. Whites could (and did) claim that Black people, free and enslaved, were innately “inferior.” They could (and did) question whether Black people were capable of comprehending political ideals like liberty and equality, even when petitions or the prospect of violent revolt by the enslaved clearly proved otherwise. Most eighteenth-century whites denied that Black people deserved to enjoy the same political rights as white American citizens.

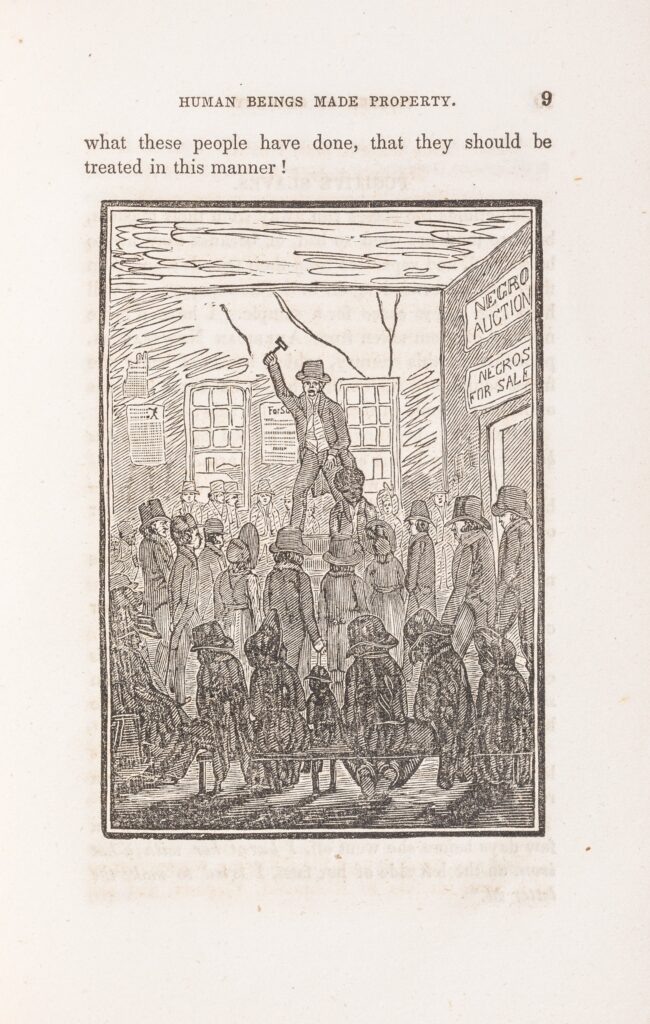

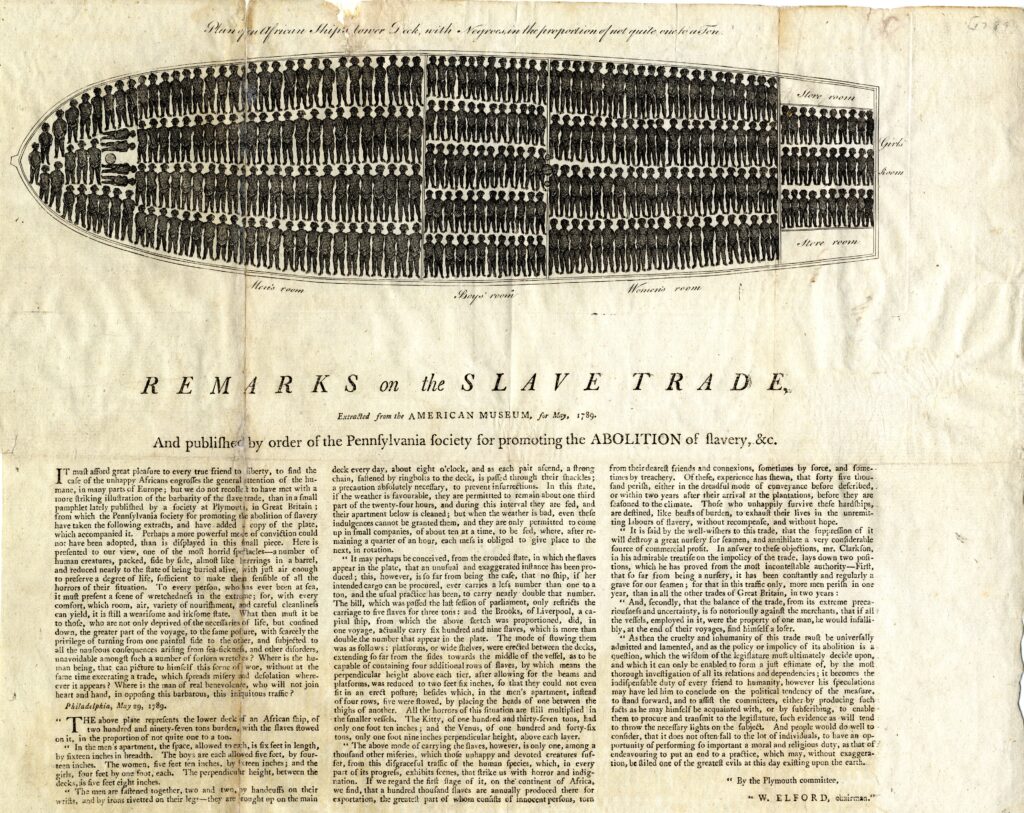

Yet none of these arguments should be taken as evidence that white people patently refused to acknowledge, let alone were somehow incapable of knowing, that Black people, free and enslaved, were people. Critics of the three-fifths clause, especially Northern antifederalists, stressed the personhood of the enslaved to underscore how brutal slavery and the trans-Atlantic slave trade was. A New York antifederalist, writing under the pseudonym Brutus, did precisely this in the fall of 1787. “What adds to the evil is, that these states are to be permitted to continue the inhuman traffic of importing slaves, until the year 1808,” the pseudonymous Brutus explained in his third letter, linking the three-fifths clause to Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution, which forbade Congress from “prohibit[ing]” the slave trade “prior” to that year. “[A]nd for every cargo of these unhappy people, which unfeeling, unprincipled, barbarous, and avaricious wretches, may tear from their country, friends and tender connections, and bring into those states, they are to be rewarded by having an increase of members in the general assembly.”

Frightening as that was, the prospect of increased, perhaps insurmountable Southern power was not the only concern on many Northerners’ minds. Another was what including three-fifths of the enslaved population in each state implied about the relative equality of Black and white people. Abraham Fuller, a delegate at the Massachusetts ratifying convention, thought “the rule of proportion . . . five slaves to three freemen” was “but equal, for slaves are but chattels.” But his colleague, Francis Shurtliff (spelled “Shurtleff” in Theophilus Parsons’ notes), “want[ed] to know whether five smart negro slaves are to be equal to three of our children.”

This was the most typical way to characterize the three-fifths clause: not as a fraction (“three-fifths of a person”), but as a ratio (“five slaves” treated “equal to three freemen”). The point was to stress the comparative representation of enslaved and free people, and often, to compare the relative value of enslaved and free labor, not to claim that the Constitution rendered each enslaved person forty percent less human than their free counterpart. Not all enslaved Black people would count toward apportionment. That could certainly be interpreted as a reflection of “inferiority”: of enslaved labor, of enslaved laborers, or of Black people more generally. Any given white person could hold one or more of these views at the same time. But none meant that enslaved Black people were not people. That very fact provoked the cringeworthy comparison between “smart,” productive “negro slaves” and white children at the Massachusetts ratifying convention. It was also on the mind of North Carolina antifederalist William Goudy, who combined this worry with concern about direct taxes in one blunt statement: “I wish not to be represented with negroes,” Goudy stated flatly, “especially if it encreases my burthens.”

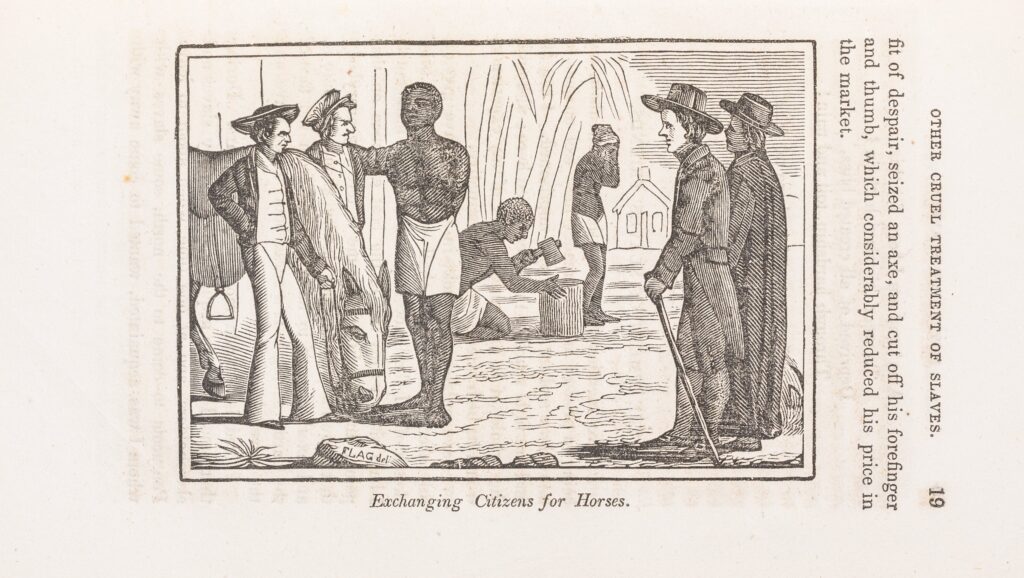

To emphasize the hypocrisy of Southerners’ insistence that slaves were “property,” and to challenge the political advantage Southern states stood to gain courtesy of the three-fifths clause, Northerners frequently compared Black people to beasts of burden. For all his sympathy for human victims of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, Brutus made this very comparison in the very same letter in which he referred to enslaved Africans as “unhappy people”: “If this be a just ground for representation, the horses in some of the states, and the oxen in others, ought to be represented,” Brutus wrote. “For a great share of property in some of them, consists in these animals; and they have as much controul over their own actions, as these poor unhappy creatures, who are intended to be described in the above recited clause, by the words, ‘all other persons.’” Dehumanizing comparisons like these reflect Northern white fears of both increased Southern political power, on the one hand, and even the remote possibility of Black citizenship, on the other. The personhood of the enslaved lay at the heart of both fears. The point of such comments was to claim that because Southerners called enslaved people “property,” it made as much sense to count animals owned by Northern whites toward apportionment as it did to count enslaved people owned by Southern enslavers. Which was to say, not at all.

By our twenty-first century standards, that argument is absurd. It was absurd by eighteenth-century standards, too. And federalists, especially those from the South, had a ready answer. Three-fifths of the enslaved population counted toward apportionment, and beasts of burden didn’t, because enslaved people were not animals. This claim was in no way incompatible with either whites’ widespread belief in Black “inferiority,” or enslaved people’s legal status as “property.” Slaves, federalists countered, were persons, just as the Constitution said they were.

“It is true, that slaves are property,-but are they not persons too?” one Southern federalist, writing under the pseudonym A Native of Virginia, asked readers: “Does not their labour produce wealth? And is it not by the produce of labour, that all taxes must be paid?” Enslaved peoples’ general status as subordinates to free persons, and their more specific status as wealth-producing possessions of their masters that had monetary value of their own, did not change the fact that they were people. “The Convention justly considered them in the light of persons, rather than property,” A Native of Virginia continued, “But at the same time conceiving their natural forces inferior to those of the whites; knowing that they require freemen to overlook them, and that they enfeeble the State which possesses them, they equitably considered five slaves only of equal consequence with three free persons.”

A Native of Virginia was addressing Southern criticism that focused on the potential tax burden the three-fifths clause imposed. Referring to enslaved people’s “natural forces” as “inferior” and clearly distinguishing between “three free persons” and “five slaves,” A Native of Virginia nonetheless challenged Southerners who might be “accustomed to consider their slaves merely as property; as a subject for, not as agents to taxation.” A Native of Virginia reminded readers that that was not all enslaved people were. The three-fifths fraction provided due consideration for enslaved people as property whose labor and bodies were sources of wealth, and as persons fundamentally different from beasts of burden. That was why not all of them would count toward apportionment, like free persons, but it was also why not all of them would be subject to “direct taxes,” either. “What rule of federal taxation so equal, and at the same time so little unfavourable to the southern States,” A Native of Virginia asked readers, “could the Convention have established, as that of numbers so arranged?” Thus, the argument went, the three-fifths clause ought to satisfy those inclined to believe representation should be based on wealth, and those who believed it should be based on population, since enslaved people counted in both categories.

This was why Southern federalists saw no contradiction in calling slaves “property,” and no shame in admitting that counting three-fifths of the enslaved population alongside all of the free population “was highly favourable to the southern interest.” A pseudonymous federalist, An American, reminded Southerners how much they stood to gain if the Constitution were ratified. “By the present arrangement, you may enjoy the weight and power of five votes and a half for 168,000 slaves, being three fifths of your whole number of blacks,” An American told members of the Virginia ratifying convention in a piece published in a Pennsylvania newspaper in May 1788. “Power has been given to your state with no sparing hand. You (suffer me respectfully to say so) of all the members of the union, appear to have the least cause of complaint.” What made it possible was that enslaved people were people, not merely possessions. Whatever tax burden Southern states would carry would come with additional representation: a more than fair trade-off by any estimation.

This argument for Southern power also proved compatible with the very arguments that Northerners brought up to disparage Southern slavery: that slavery was inherently less efficient and productive than Northern “free” labor, and that it was inherently more risky because slaves could revolt at any time. Both these inherent risks, and the advantages the South stood to gain if the Constitution were ratified, stemmed from the simple fact that enslaved people were people. In fact, the very risks inherent to slavery justified the power the Constitution conferred on slave states. Some “who opposed an unlimited importation” of Africans, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney told his colleagues in January 1788, thought slaves dangerous because they could be convinced by “an invading enemy” to “turn against ourselves & the neighbouring states, and that as we were allowed a representation for them in the house of representatives, our influence in government would be increased in proportion as we were less able to defend ourselves.” The very fact that slave societies were more vulnerable to revolts because slaves were people made it all the more necessary that Southern states receive some consideration for them in the Constitution. An American called them “a dangerous species of population,” and believed that, “when proper arrangements shall be made and occasion shall require,” the South “can rely on the most useful and friendly aid from the north.” In other words, the protections required to maintain this system of enslaving people would, in effect, bind the Northern and Southern states together via a shared interest in maintaining security from slave violence.

Collectively, Southern federalists pointed to the personhood of the enslaved to argue that whatever power the Constitution vested in slave states via the three-fifths clause was not the outrageous act of rank hypocrisy that Northern antifederalists made it out to be. Rather, the three-fifths clause prudently reflected slaves’ dual status of property and persons simultaneously. A Constitution that denied either status completely would not distribute political power and potential tax liability in a way that reflected the basic reality of slavery as an economic system or as a legal regime that rested fundamentally on the coerced labor of human beings.

That was Madison’s point. Because an enslaved person worked for a master, and not for themself, and because an enslaved person could be sold, brutalized, and chained by their enslaver, that enslaved person “may appear to be degraded from the human rank, and classed with those irrational animals, which fall under the legal denomination of property.” But Madison argued that that understanding was incomplete. The enslaved were also “no less evidently regarded by the law as a member of the society; not as a part of the irrational creation; as a moral person, not as a mere article of property.” This was not simply because they were “protected” from brutalization unlike other forms of property and “punishable” for offenses, Madison explained. It was rather because the law deemed it so. The “mixt character of persons and of property”—what Madison called enslaved people’s “true character”—“is the character bestowed on them by the laws under which they live; and it will not be denied that these are the proper criterion; because it is only under the pretext that the laws have transformed the negroes into subjects of property, that a place is disputed them in the computation of numbers; and it is admitted that if the laws were to restore the rights which have been taken away, the negroes could no longer be refused an equal share of representation with other inhabitants.”

Madison admitted that this benefited Southern states. But Northerners could not have it both ways. They could not count the enslaved “in some degree as men, when burdens were to be imposed,” but omit them from the apportionment tally by arguing they were strictly property. They could not “reproach the southern States with the barbarous policy of considering as property a part of their human brethren” and then turn around and “contend that the government to which all the States are to be parties, ought to consider this unfortunate race more compleately in the unnatural light of property, than the very laws of which they complain!” The Constitution already counted “other inhabitants” (like white women and children, though Madison did not list these examples specifically) on a one-to-one basis with free white men. By this measure, Madison suggested, counting three-fifths of the enslaved population was something of a bargain for the North. Would Northerners prefer all slaves counted toward apportionment?

For Madison, as for other defenders of the three-fifths clause, an enslaved person was not “three-fifths of a person” because they were their master’s property any more than they were only “three-fifths” the property of their master because they were a person. It should be obvious that none of this makes slavery more “humane.” It means that the Constitution gave enslavers a vested interest in acknowledging that the people they claimed as “property” were people. The three-fifths clause allowed enslavers to exploit the humanity of people they enslaved, to use the fact of their personhood, for political gain. Whether defending or criticizing the three-fifths clause, participants in the public ratification debate were convinced that how the Constitution treated enslaved people—as “property” and as “persons”—would be the key to the future of slavery, Southern power, and racial hierarchy.

Further Reading

Primary sources related to the three-fifths clause and the ratification of the Constitution may be found in:

The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution Digital Edition, ed. John P. Kaminski, Gaspare J. Saladino, Richard Leffler, Charles H. Schoenleber, and Margaret A. Hogan (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009).

Secondary sources:

Mary Sarah Bilder, Madison’s Hand: Revising the Constitutional Convention (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017).

Robin Einhorn, American Taxation, American Slavery (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2006).

Jan Ellen Lewis, “The Three-Fifths Clause and the Origins of Sectionalism,” in Barry Bienstock, Annette Gordon-Reed, and Peter S. Onuf, eds., Family, Slavery, and Love in the Early American Republic: The Essays of Jan Ellen Lewis (Charlottesville: The University of Virginia Press, 2021), 254-80.

Jan Ellen Lewis, “What Happened to the Three-Fifths Clause: The Relationship Between Women and Slaves in Constitutional Thought,” Journal of the Early Republic 37 (Spring 2017): 1-46.

Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010).

Matthew Mason, Slavery & Politics in the Early American Republic (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

Leonard L. Richards, The Slave Power: The Free North and Southern Domination, 1780-1860 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000).

David Waldstreicher, Slavery’s Constitution: From Revolution to Ratification (New York: Hill and Wang, 2009).

Sean Wilentz, No Property in Man: Slavery and Antislavery at the Nation’s Founding (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019).

Christopher D. E. Willoughby, Masters of Health: Racial Science and Slavery in U.S. Medical Schools (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2022).

This article originally appeared in September 2024.

Nathaniel C. Green is Professor of History at Northern Virginia Community College. A specialist in early U.S. political culture, he is the author of The Man of the People: Political Dissent and the Making of the American Presidency (University Press of Kansas, 2020; paperback, 2024). He is currently at work on a book-length study of the three-fifths clause, tentatively titled Three Fifths: The Constitution, Slavery, and the Toxic Politics of Compromise.