We are used to hearing stories of Captain Cook, Captain Bligh, and the other big names of Pacific exploration. Their adventures have captivated countless readers since the middle of the eighteenth century. There was another set of explorers, though, who were travelling alongside these Europeans. And their stories are no less dramatic or remarkable.

As Greg Dening observes elsewhere in this issue, Pacific Islanders have always been adept travelers. Their history is filled with long-distance sea navigations, far migrations, inter-island trade, and inter-island battles. When European ships started anchoring by Tahiti, New Zealand, Hawai’i, or the islands of Micronesia, there were islanders who found the prospect of a new type of voyaging appealing. They decided to join some of the onward journeys. Ahutoru, a Tahitian, left with Louis Antoine de Bougainville and in 1769 became the first Pacific Islander to visit Europe. He enjoyed the charms of Paris for a year before boarding a ship that would have, had he not caught smallpox on the way, returned him to his island. Another well-known figure is Mai (Omai), visitor to Britain and one of the few among these travelers to survive the trip and return home. Less familiar are the names of Tupaia, Taiato, or Hitihiti; men who went exploring with Cook, and whose stories are included here.

The attractions of a trip with a British or French crew were sufficient to inspire many young men to present themselves as willing navigators, translators, or sailors. It was primarily young men who asked to go. (One woman stowed away on Cook’s ship Resolution before it left Tahiti to catch a lift to nearby Ra’iatea but she was an exception.) The reasons the young island men had for embarking varied, but there were social advantages in associating with exotic foreigners and in acquiring European goods and firearms. There was also the tantalizing opportunity to extend their horizons.

What follows is a simple telling of some of these men’s stories, short reductions of great yarns. But we must tell these tales: doing so offers some insurance that these dynamic, colorful strands are not omitted from the weave of Pacific history.

Tupaia: navigator and translator

When Captain Cook anchored in a bay on the northern coast of Tahiti for the first time in April 1769, he met Purea, the most powerful woman on the island. He also met her collaborator, a priest from the island of Ra’iatea named Tupaia. They were working towards a monopolization of the island’s sacred and political power. Tupaia was a respected figure in the Society Islands and something of a virtuoso. A member of the elite arioi society of travelers and performers for the god ‘Oro, he was a ritual specialist, skillful navigator, and negotiator. He had also witnessed in 1767 the extraordinary visit of the first ship from beyond the Pacific: Samuel Wallis’s Dolphin. He knew something of what to expect from these visitors. He established a friendship with the naturalist Joseph Banks, helped Cook in relations with chiefs and learned from the ship’s artists how to draw in European style. Near the end of the Endeavour’s stay he announced he was going to accompany them to England. Cook and Banks, on the lookout for a guide, felt he “was the likeliest person to answer our purpose.”

After leaving Tahiti, the Endeavour made several stops among the Society Island archipelago. In each place Tupaia used the correct ceremonial forms when greeting the chiefs, easing some of the tensions of these early meetings across cultural divides. In August they departed, as Banks said, “in search of what chance and Tupaia might direct us to.”

They steered southward towards New Zealand, to try to determine if it was the northern tip of a great southern continent. Tupaia drew maps and read the currents, weather, and sky. On reaching New Zealand, Tupaia helped establish working relationships between the Maori people and the European visitors. He was able to translate, as the language of the Society Islands was the original basis of the language of the Maori. His lineage was important: he was from the Maori’s ancestral homeland, Hawaiki (Ra’iatea), and was seen to hold substantial spiritual power (mana). There were still violent clashes and misunderstandings. Tupaia, though, created a lasting impression on Maori communities and it was the great priest, rather than Cook or Banks, who was most persistently asked after when voyagers stopped by.

After establishing that the two islands of New Zealand were not the bountiful continent they sought, Cook and his men departed for the east coast of Australia. In April 1770, Cook tried to land with a few officers, the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks, and Tupaia in a bay that would later form part of Sydney. Two men (of the Gweagal or Eora people) met them with shouts and spears. Tupaia tried in vain to find any words in common and Cook offered gifts, but the visitors only managed to get ashore after firing on the men. Without the ability to obtain food and information from the locals, Cook had to continue on up the coast. Tupaia was of help in northern Australia, when he was able to establish a trusting relationship with the Guugu-Yimithirr people.

From Australia, the voyagers made their way to Dutch Batavia (present-day Jakarta). There, in December 1770, Tupaia and his servant Taiata fell ill. Dismayed at ever having left Tahiti, Tupaia died a few days after Taiata.

Mai meets George III

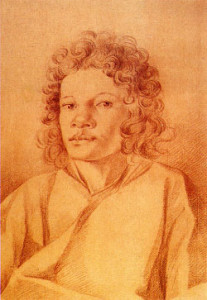

The most well-known Pacific traveler of the Age of Enlightenment is Mai (fig.2), a Ra’iatean who joined Cook’s second voyage at the Island of Huahine. Mai was born around 1753 into the ra’atira, a land-owning class. Like Tupaia, he had been exiled from his home island by the warriors of Bora Bora. He had also lost his father to them and remained bent on revenge. In September 1773 when Cook’s two vessels arrived, Mai saw an opportunity. He struck up some friendships with the men on the Adventure and, as he bragged to his compatriots, decided to travel to England and get the weapons he needed to avenge his father’s death.

Mai did not have the linguistic experience of the better-travelled Tupaia, but during the voyage he―and his fellow Society Islander, Hitihiti―helped the ship’s two naturalists, Johann and George Forster (father and son) with a vocabulary of the Tahitian language as well as with the ship’s relations in Tonga and New Zealand. Things did not run happily with the Maori they met, a rash of offenses being made against each side. After one incident in Queen Charlotte Sound on the south island, Mai went with one of the officers to look for a party of ten who had gone missing while collecting greens. They found them, cut up and being roasted. The Adventure had by this time lost company with Cook’s Resolution. Shocked and disheartened, Mai and the crew left New Zealand. Captain Tobias Furneaux, Cook’s second in command, directed their course back to England, eastward through empty, freezing latitudes, erasing hope of finding a southern continent.

In England Mai met the crème of English society, including the king and queen. Those at the royal reception applauded his grace, good humor, and charming manners, and extended a shower of dinner invitations. Mai’s chaperone, Sir Joseph Banks, was happy to promote his protégé, introducing him to the foremost figures of science, art, politics, and literature, and taking him on tours of cities and country estates. Mai learned to dance in the English manner, to shoot, to play chess, to ice-skate, and to read and write English. Philosophic debates in Europe on the nature of civilization were given extra fuel by observations of Omai’s “natural” civility, and the education he was receiving (containing so little Christian instruction) became a matter of public controversy. As interesting as his English experiences might have been, Mai retained his desire to return to Ra’iatea.

King George III had already promised a ship to return Mai to the Society Islands and the Admiralty Board was eager to find the coveted Northwest Passage, a theorized northern water route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Cook was the natural choice for the voyage and in the summer of 1776, just as the Americans were declaring their independence, he set sail on his third and final Pacific expedition.

On reaching the Society Islands in August 1777, the voyagers spent time in Tahiti and Moorea, then established Mai in Huahine (near Ra’iatea) on a piece of land where the crew assembled a prefabricated house for him. Mai’s English possessions ranged from pistols, ammunition, a suit of armor, cutlasses, a pair of horses and a monkey, model buildings, toy soldiers, an organ, a jack-in-a-box, and an electrical apparatus. He was not as careful as he should have been in distributing his gifts, but retained enough weapons and supporters within Huahine to achieve his desired military victory over the Bora Borans. He did not have long to celebrate. He died of a fever only two and a half years later.

Hitihiti’s Polynesian and Antarctic adventures

Hitihiti was as much an adventurer as Mai (fig. 3). He was of higher rank, being linked to the Puni chiefly line of Bora Bora, the most westerly of the Society Islands and home of Mai’s enemies. While Mai was negotiating to travel on Captain Furneaux’s Adventure, Hitihiti was volunteering for a place on Cook’s Resolution. Like many islanders, Hitihiti (also known by his former name, Mahine), had a workable command of English, was judged to be personable, and was accepted as a crewmate by the British mariners.

During the ships’ next stop, in Tonga, Hitihiti and Mai found that red feathers, a potent and sacred item in Polynesia, were abundantly available. They bartered for what they could of the feather-decorated clothes and lengths of cloth made of beaten bark (tapa). Hitihiti advised Cook to do the same; he knew how valuable they would be as trade items back in Tahiti. This advice was to prove important: at several points along the journey the islanders they were meeting would only give up pigs and other provisions in return for some of these feathers.

In March 1774, after spending over a hundred days at sea and desperately in need of food, the Resolution’s crew finally sighted the coast of Rapa Nui (Easter Island). The first islander to come on board was bombarded with questions; Hitihiti tried to make some headway but was constantly interrupted. He went ashore with the officers and although the island was bare, hot, and parched, some food was available for trade. Hitihiti’s eye was caught by the peoples’ carvings of human figures, feather headdresses, and a carved wooden hand. He managed to barter his lengths of tapa, a valuable commodity in Rapa Nui, for some of these items. He later gave the wooden hand to the Forsters, who in turn donated it to the British Museum, where it can be seen today.

Leaving Rapa Nui, Hitihiti’s verdict was “a bad land, a good people.” He was more pleased by the Marquesas, similar in so many ways to his own island home. He was also delighted with his visit to Takaroa, of the Tuamotu Archipelago, where he was able to secure some dogs with white, long hair of the sort valued for warriors’ ornaments in Tahiti. Returning to the Society Islands, though, was Hitihiti’s greatest moment of triumph. As the ship anchored in Matavai Bay in Tahiti, the people were amazed to see him there on deck, in European clothes, with an unsurpassed collection of exotic objects and red feathers. He was an instant celebrity. People flocked to hear his stories, women flocked to his bed, and people of ambition scrambled for his support.

Hitihiti decided to remain within the Society Islands rather than travel on to Europe. His fortunes waxed and waned, but he was still able to retain some of the advantages of his experiences. He also retained his role as friend of the British. In 1777 Cook met up with him and presented gifts from the British Admiralty and a personal gift of a chest of tools. William Bligh dined with him in 1788 during the Bounty expedition and, on returning in 1792, heard that Hitihiti had gone with Captain Edwards of the Pandora in search of the Bounty mutineers. His appetite for adventure seems to have been undimmed.

New Horizons

There were others; the Maori chief’s son Te Weherua and his friend Koa who went with Cook to Tahiti; Lebuu, son of the Palauan Ibedul, who traveled to Canton and England. The risk they all took in embarking with Europeans was that they would never return home. Like Ahutoru, Tupaia, and Taiata, the aspirations of the Maori and Palauan boys were defeated by European disease.

From the late eighteenth century an increasing number of European ships made stops at the islands of the western as well as the eastern Pacific, opening up more opportunities for travel. Islanders started to accompany missionary ships from the late 1790s as they took on the role of “native teachers” to help in the work of Christianizing the Pacific. In the decades that followed, increasing numbers of islanders would take to the sea aboard the many trading, whaling, missionary, and settler ships arriving in the region. Although some of this traffic represented the grim lurch of the colonial labor trade, islanders continued to employ the ships to their own ends.

Further Reading:

The cross-cultural histories of the Cook voyage are explored most effectively and enjoyably by Ann Salmond, The Trial of the Cannibal Dog (London, 2004) and Nicholas Thomas, Discoveries: The Voyages of Captain Cook (London, 2003). Cook’s shipboard journals have been edited by J.C. Beaglehole, The Journals of Captain James Cook, 4 vols. (Cambridge, 1955-67). For more on each of the islanders, see Salmond and Thomas as above, and also, for Tupaia: Greg Dening’s Performances (Chicago, 1996) and chapters in M. Lincoln, ed. Science and Exploration in the Pacific (Suffolk, 1998). Tupaia’s watercolors are in the British Library. For more on Mai, see E.H. McCormick, Omai: Pacific Envoy (Auckland, 1977) and Francesca Rendle-Short, ed. Cook and Omai: The Cult of the South Seas (Canberra, 2001). On Hitihiti, see Nicholas Thomas and Oliver Berghof, eds. A Voyage Round the World by George Forster (Honolulu, 1999). On Li Buu (Lee Boo): K. Nero and N. Thomas, eds., An Account of the Pelew Islands (London: 2001).

This article originally appeared in issue 5.2 (January, 2005).

Jenny Newell is a curator (Polynesia) in the Department of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, British Museum. She is writing a doctoral thesis on cross-cultural exchanges and ecology in eighteenth-century Tahiti.