After that, Wheatley and Wooldridge’s lives followed surprisingly parallel courses. Both experienced a rise in status, boosted by aristocratic patrons within British imperial society, only to suffer from the disruption of the American Revolution. Wheatley became a published author, gained her freedom, married John Peters, and had children, but could not finance a second collection of poetry in the straitened economy of wartime America. Phillis Peters died young in 1784.

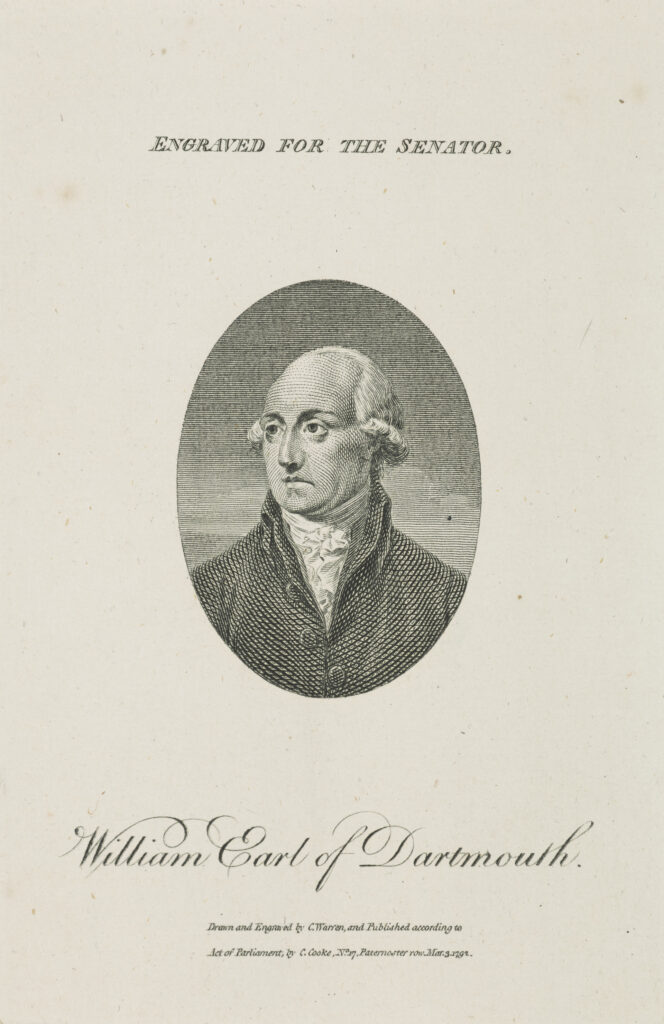

As for Thomas Wooldridge, after his father-in-law William Kelly died in 1774, he became the business partner of Susanna’s brother Henry and assumed her father’s role as a leader among the London merchants doing business in America. Wooldridge met with such prominent advocates for the colonies as Edmund Burke and Josiah Quincy Jr. and testified to Parliament about shipping losses. In November 1775 the Earl of Dartmouth was replaced as Secretary of State, but Wooldridge no longer needed his patronage. London property-owners elected him as an alderman in 1776, and then he was chosen sheriff of London and Middlesex.

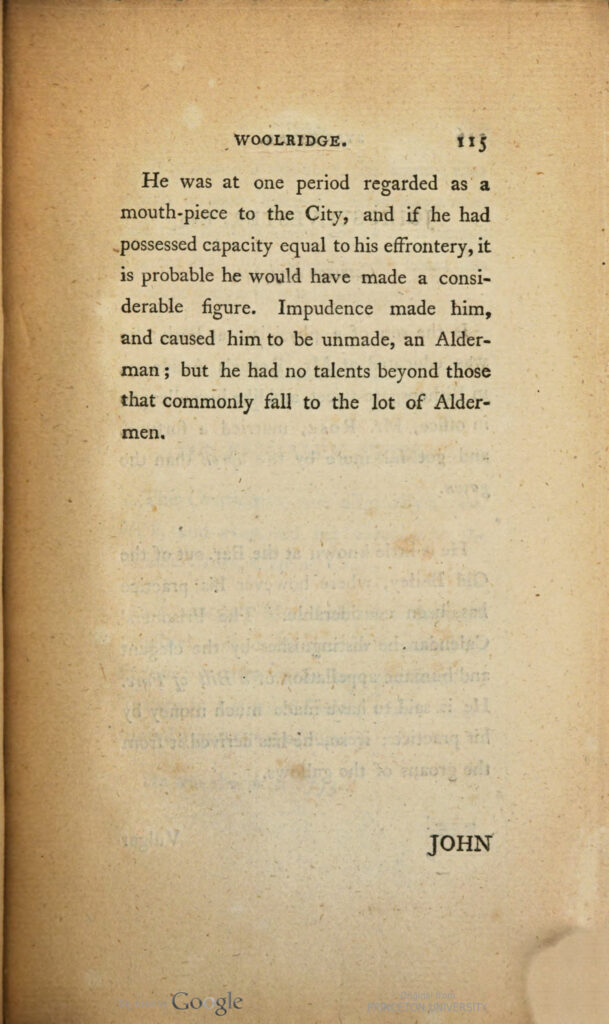

By that time, however, the war with America and the death of Henry Kelly in 1776 had forced the firm of Wooldridge and Kelly into bankruptcy. Wooldridge kept his seat as an alderman and the sympathy of the London press through the war—evidently people accepted that the business failure was not his fault. But peace brought an end to that stasis. Citizens now complained that the alderman was corruptly squeezing money from his office. Wooldridge was locked in debtors’ prison in 1783 and had to declare bankruptcy again, this time to a much less understanding response. The other aldermen took the unprecedented step of stripping Wooldridge of his seat. A 1799 publication looked back on him and declared: “Impudence made him, and caused him to be unmade, an Alderman.” Nonetheless, the city continued to provide Susanna Wooldridge with substantial sums, “independent of her husband, for the support of herself and her children.” This pension helped support her through the lawsuits over the Wooldridge and Kelly debts, which lasted for years on both sides of the Atlantic.

Financially broken, Thomas Wooldridge made his way back to America alone. In January 1794, at the age of fifty-four, he died in Boston, ten years after Phillis Wheatley had died in the same town.

Further Reading

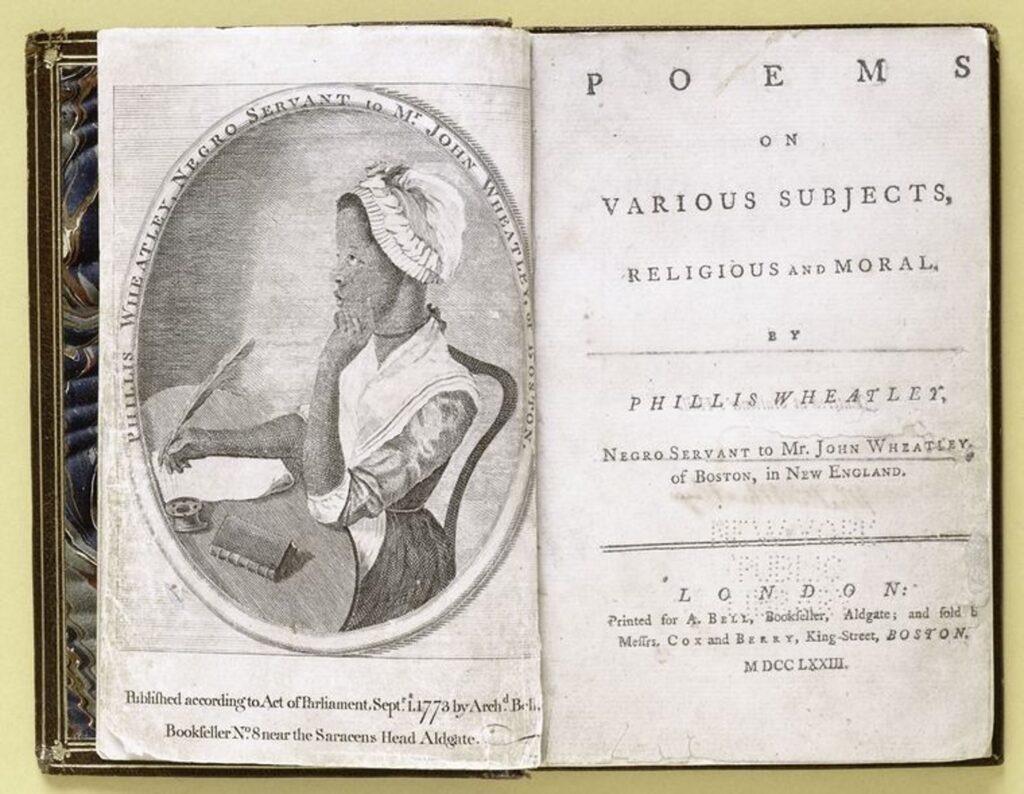

Vincent Carretta wrote the first thorough biography of Phillis Wheatley, published in 2011 under the title Phillis Wheatley and republished with new material as Phillis Wheatley Peters: Biography of a Genius in Bondage (Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 2023). David Waldstreicher’s The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley: A Poet’s Journeys Through American Slavery and Independence (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2023) analyzes her poetry in the context of specific moments in her life, including a detailed discussion of her response to Wooldridge’s challenge in 1772.

Carretta also edited Wheatley’s Complete Writings for Penguin Classics (2001), building on John Shields’s The Collected Works of Phillis Wheatley (1988). However, possible new poems continue to be identified, most recently by Waldstreicher (“Anonymous Wheatley and the Archive in Plain Sight: A Tentative Attribution of Nine Published Poems, 1773-1775,” Early American Literature 57, no. 3 (2022): 873-910) and Wendy Raphael Roberts (“‘On the Death of Love Rotch,’ a New Poem Attributed to Phillis Wheatley (Peters): And a Speculative Attribution,” Early American Literature 58, no. 1 (2023): 155-84.

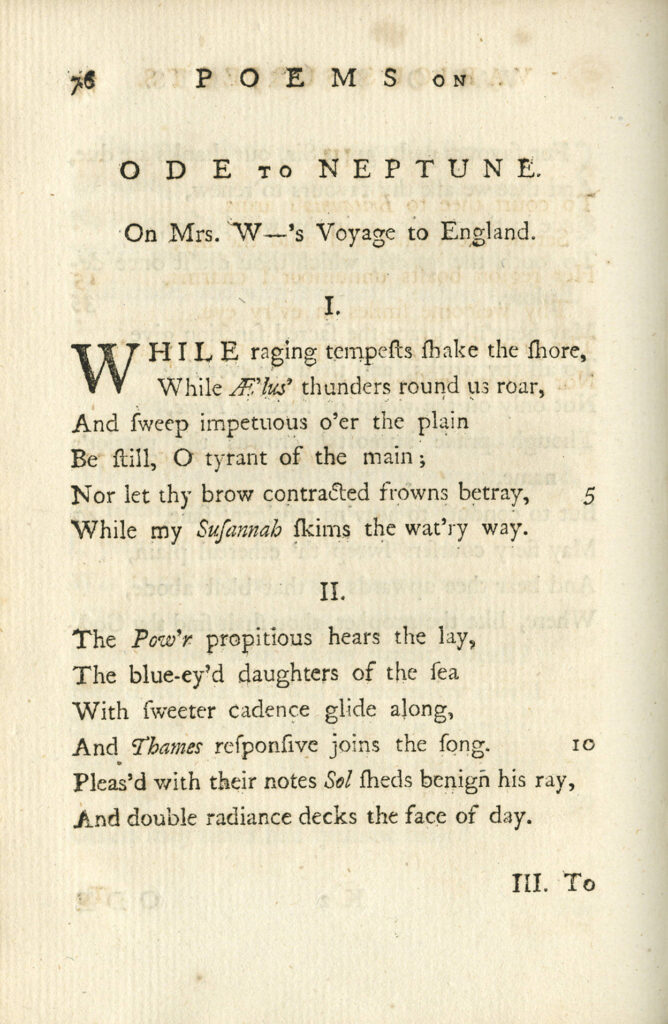

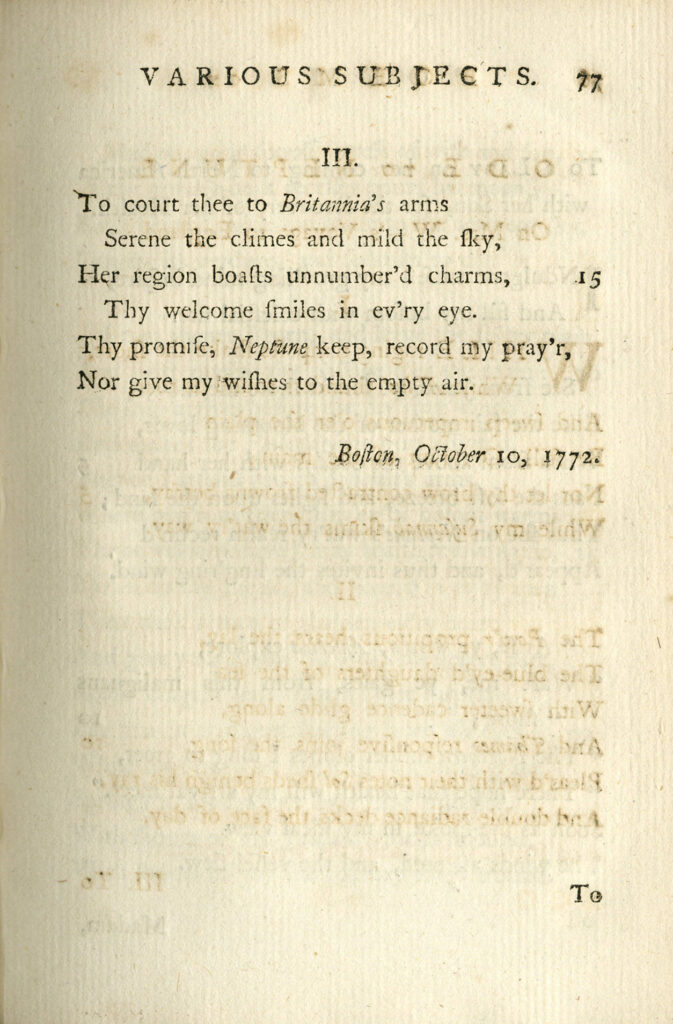

There are many interesting literary studies of Wheatley’s poetry and explorations of her significance in African American culture. Some discussions of Wheatley are based on myths or misunderstandings, however, and analyses of “Ode to Neptune” based on identifying its “Mrs. W—” as Susannah Wheatley or Patience Wright are among them. James Rawley explored the importance of Wheatley’s entry into the evangelical circle of the Countess of Huntingdon and the Earl of Dartmouth in James A. Rawley, “The World of Phillis Wheatley,” New England Quarterly 50, no. 4 (Dec. 1977): 666-67.

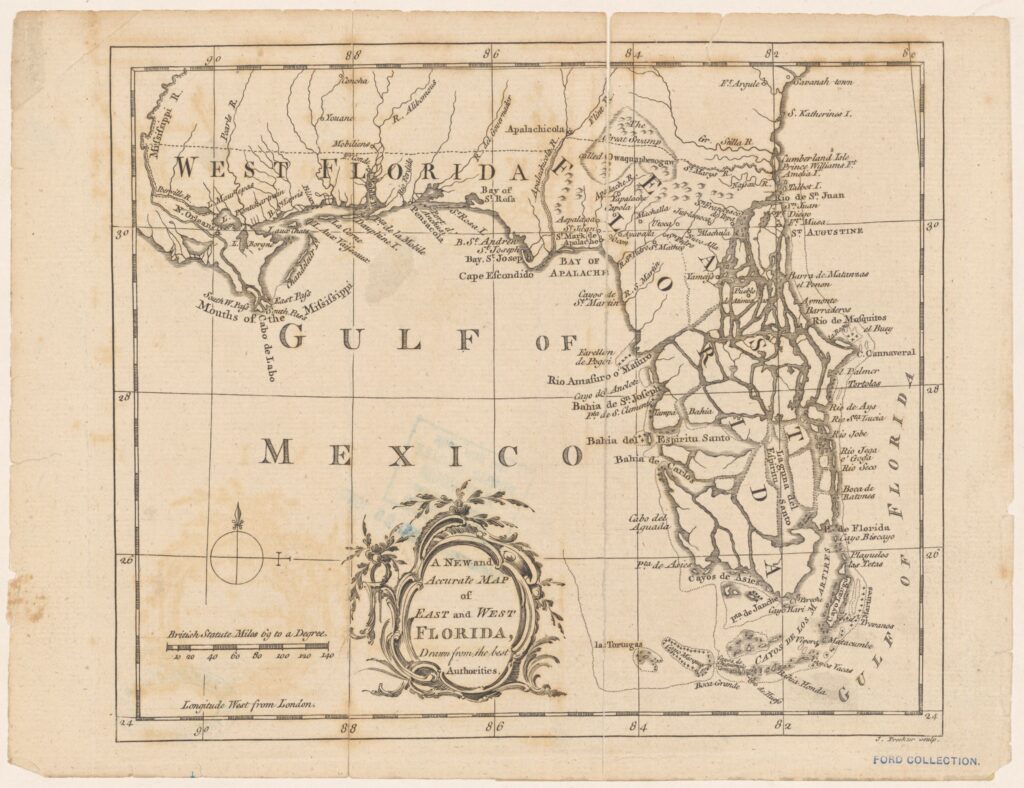

Thomas Wooldridge’s upward career can be tracked through his correspondence in The Manuscripts of the Earl of Dartmouth, vol. 2: American Papers (London: H. M. Stationery Office, 1895); Charles Loch Mowat, East Florida as a British Province, 1763-1784 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1943); and “Debates of a Political Society” in the London Magazine and Monthly Intelligencer, vol. 44 (1775), 333-41. His downward career is evident in The Swindler Detected: or Cautions to the Public (London: G. Kearsly, M. Follingsby, J. Stockdale, 1781); City Biography, Containing Anecdotes and Memoirs of the Rise, Progress, Situation, & Character, of the Aldermen and Other Conspicuous Personages of the Corporation and City of London (London: W. West and C. Chapple, 1799); and a death notice in the Boston Columbian Centinel, January 4, 1794. Ben Saunders has collected material for “The Thomas Wooldridge Biography Project.”

This article originally appeared in May 2023.

J. L. Bell is the proprietor of the Boston1775.net website, offering daily helpings of unabashed gossip about the people of Revolutionary New England. He is the author of The Road to Concord: How Four Stolen Cannon Ignited the Revolutionary Warand the study Gen. George Washington’s Home and Headquarters—Cambridge, Massachusetts for the National Park Service.