The man had never met Ma’lokyattsik’i, but he hardly hesitated as he drove a pickaxe through her heart and toted away her salt. Also known as the Salt Woman or Salt Mother, Ma’lokyattsik’i lived in the form of a salt lake and had long attracted visitors from the pueblos of Zuni, Hopi, Acoma, Laguna, and beyond. These visitors came with care, carrying prayer plumes and gracious sentiments. Puebloan peoples even agreed among one another to leave behind weapons and warfare at their camps and villages whenever they needed salt. Puebloan peoples have long seen the Salt Woman as an animate part of their world. But the man with the pickaxe—a Spanish soldier led by Captain Marcos Farfán de los Godos—saw her as little more than an extractable resource, one that might justify imperial investment and colonial settlement in the continental southwest.

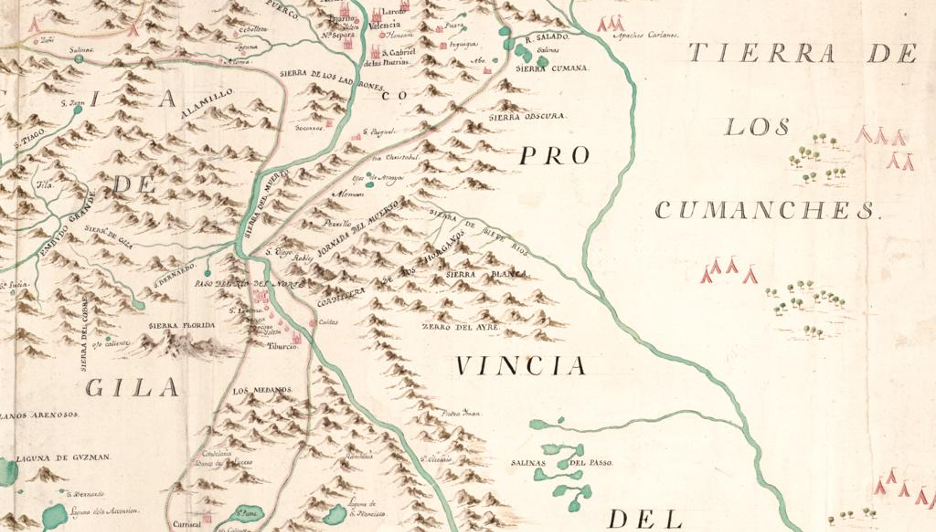

Beginning in the 1530s, Spanish expeditions invaded the North American interior in search of precious metals, profitable lands, and expendable labor. Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, Hernando de Soto, and other conquistadores often failed to find fabled cities of gold and inexhaustible silver supplies. Early Spanish invaders did, however, often find something less intrinsically valuable yet more immediately critical to their fate on the continent: they found salt. Though mundane relative to more precious minerals like gold or silver and marginal relative to colonial exports such as sugar or tobacco, local salt resources mattered deeply to the Spanish colonial project; salt sustained human and mammalian life, preserved food, and fulfilled other functions essential to survival. Access to these resources could make or break the Spanish Empire’s colonial aspirations in the North American southwest and, by extension, the continent. For most of Spain’s three-hundred-year colonial regime in the southwest, Spanish access to inland salt resources hinged upon existent Indigenous environmental knowledge, political power, and patterns of mobility and labor—precedents that long predated Spanish colonization and several of which continue to outlive it. As sites of contestation and coalescence, local salt resources were critical to the future of Indigenous polities and colonial projects across an increasingly contested corner of the continent.

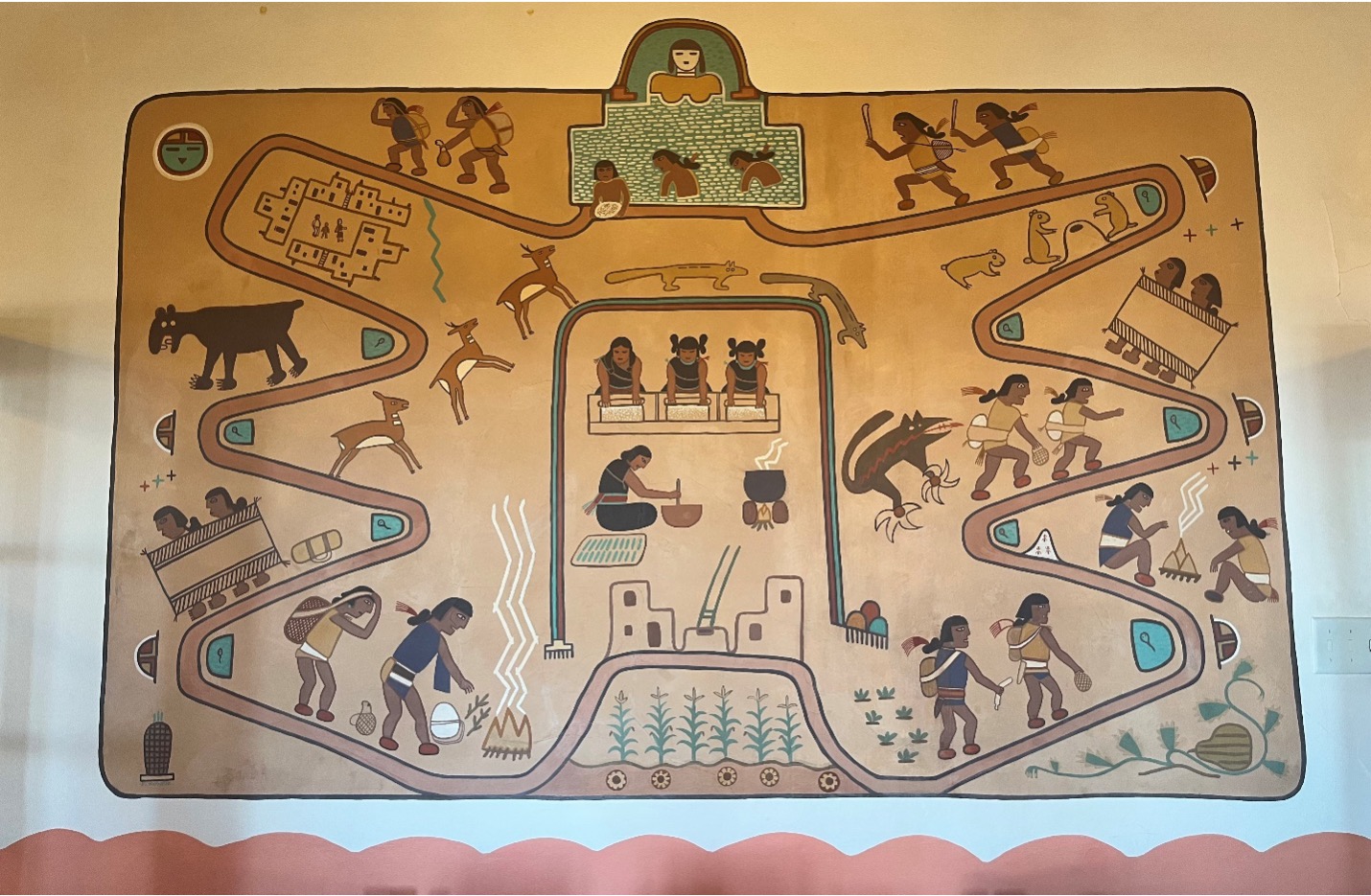

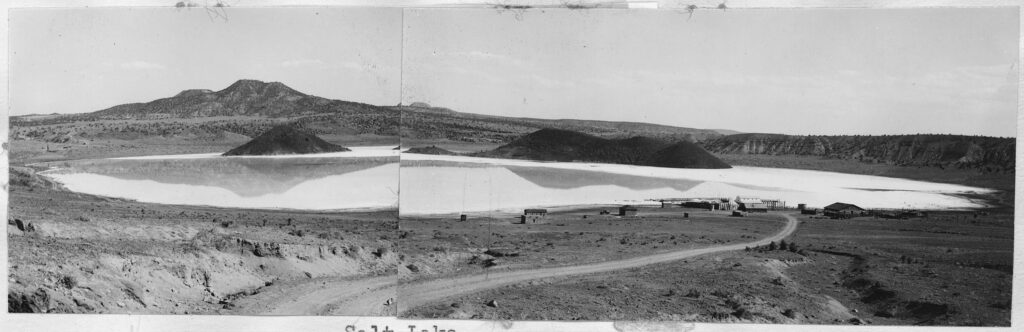

Native peoples in the southwest have long attached intrinsic value to salt resources. This includes the Zuni Salt Lake, a uniquely revered resource among many pueblos in present-day New Mexico and Arizona. According to one explanation, the Salt Woman (named Ma’lokyattsik’i, Mawa-sitsa, or Ma/k/nan/e in modern Zuni accounts) once resided at Black Rock near the Pueblo of Zuni, but wasteful Zunis who polluted her home prompted her departure. As punishment, Zunis would have to make an arduous trek from the pueblo to a remote volcanic maar some forty miles southward. Another narrative introduces the Salt Woman as a person “made of white powder” who visited the pueblos “to spread her mucous over the food,” a service shunned by the people. She then strayed far from the pueblos and allowed salt collecting rights “only to men who show respect for her.” Other pueblos articulated an affinity for salt resources in similar yet still distinctive ways. During a feast at Santa Clara Pueblo, Salt Old-Woman took human form and donned a white manta, white doeskin boots, and a white abalone shell. The feast, according to the diners, had not been properly seasoned, and so the Salt Old-Woman “rose and blew her nose into the food to salt it.” When the people refused to eat the food, she informed them “that their nearby salt lake would dry up and they would be forced to travel many miles to obtain salt” before vanishing. The Salt Old-Woman went east, past the Manzano Mountains, to live in the Estancia Valley, where over a dozen alkali and saline lakes blanket an ancient seabed. These histories may refer to pressure early Spanish colonization placed upon Puebloan peoples and the salt resources in their homelands, or they might harken to pre-colonial Puebloan pasts during which access to salt was a right to be earned through responsible stewardship. Whatever their exact origin, still-told Puebloan histories of the Zuni Salt Lake, Estancia Valley, and other resources explain the depth, delicacy, and dynamism of salt’s place in the southwest.