Howdy, friends! Some of you may already be familiar with the irreverent cowgirl I play at my blog, Historiann, which is my pseudonym as well as a blog devoted to “history and sexual politics, 1492-present.” If you read Historiann for a week or two, you know that she has a ranch somewhere out on the High Plains Desert in Colorado, where she keeps large animals, rides fences, and makes a lot of jokes about mucking out stalls and horses who have already left the barn. Historiann likes to tell you a little bit about her private life—but just a little. Readers know that she is a happily married heterosexualist, and that she likes to illustrate many of her posts with the sexy cowgirls drawn by midcentury artist Gil Elvgren, but that’s about all. Of course, Historiann is just a pseudonym for Ann Little, a mild-mannered History professor with a shockingly conventional life: I live in a one-story ranch house in Colorado—I don’t own a ranch, and both of my animals weigh in at less than 15 pounds. After nearly a decade in Colorado, I just bought my first pair of cowgirl boots!

Why do I bother to play cowgirl at nights and on weekends—shouldn’t I focus on something useful and productive, like writing my next book, learning to play the guitar and yodel cowboy-style, and/or training for the Slaughterhouse Derby Girls instead? (I’ve already got my Derby name picked out—Kitty Kitty Bang Bang. What do you think? Roller Derby is yet another world of pseudonymity!) I don’t get paid for blogging, my blog doesn’t accept advertisements, and I certainly don’t bother to put it on my curriculum vita, although Historiann is clearly linked to my professional identity and interests. My main interest in my blog is now the larger community of readers and commenters who connect me to a wider intellectual world and whom otherwise I’d never meet, work with, or encounter through any of the traditional networking strategies in academia. Forget what you’ve heard about supposedly cool Colorado college towns and so-called “liberal” academia—it’s lonely out here for a Marxist feminist early Americanist who writes eastern history. My (lightly) pseudonymous identity as a cowgirl probably plays a large part of my success in bringing folks together on the blog. I don’t want to burst your bubble, amigas, but Historiann is a lot more fun than I am—she doesn’t have any family or work responsibilities outside of writing about whatever she wants to write about, and acting as a welcoming host for guests who want to join online conversations about history, the academic workplace, feminism, contemporary politics, and the interesting intersections I find therein. Who knew that there would be 2,000-3,000 people a day interested in reading about my idiosyncratic and not necessarily interconnected interests? My playful pseudonymous identity helps pull it all together. (And, I think a lot of you eastern “Dudes” are pretty easy marks!)

In the crested buttes and slot canyons of the Internet that comprise the academic blogosphere, pseudonymity has been controversial. Every once in a while, a blogger who blogs under hir own name and professional identity writes a blog post about how pseudonymous bloggers are somehow dishonest or disreputable because they might engage in fabulism, or because they’re not living up to a (non-existent) shared ethic of blogging, which then erupts into what we in the biz call a “blog $hitstorm” when a bunch of pseudonymous bloggers write defensive posts about why they’ve chosen pseudonymity, or patiently explain yet again the differences between pseudonymity and anonymity. (For example, see “A Compendium of Posts about Blogging under a Pseudonym” by English professor and pseudonymous blogger Dr. Crazy.) Although I’m not truly pseudonymous, since my real life identity is clear on my blog on the “About Historiann” page, I want to speak up in defense of pseudonymity as a vital tradition in American letters, whether those letters are pixels on a screen or printed on a page. Being able to blog under my own name with only a playful pseudonym is a privilege of tenure as well as truer to my personal style—and since college and university faculty now work in a world in which fewer than half of us are even eligible for tenure, pseudonymity in the academic blogosphere is something that encourages and protects correspondence from graduate students, adjunct or temporary faculty, or untenured faculty. Pseudonymity might be a weapon of the weak, but it can play a strong role in building communities of likeminded scholars.

As many of the readers of this journal know, pseudonymity launched the career of Benjamin Franklin nearly 300 years ago. In an outrageous act of literary transvestism, the sixteen-year-old Franklin wrote in the voice of a middle-aged widow he called Silence Dogood, and under cover of night, slipped her letters under the door of his brother James’s newspaper, The New England Courant. For six months in 1722, the satirical dispatches attributed to Dogood appeared in the Courant and poked fun at Boston’s Puritan establishment. Franklin explains the elaborate ruse in his Autobiography:

But being still a Boy, and suspecting that my Brother would object to printing any Thing of mine in his Paper if he knew it to be mine, I contriv’d to disguise my Hand, and writing an anonymous Paper I put it in at Night under the Door of the Printing House. It was found in the Morning and communicated to his Writing Friends when they call’d in as usual. They read it, commented on it in my Hearing, and I had the exquisite pleasure, of finding it met with their Approbation, and that in their different Guesses at the Author none were named but Men of some Character among us for Learning and Ingenuity.

Franklin’s “young Genius. . . for Libelling and Satyr” was not the direct cause of his brother’s censure and month of imprisonment for offending Massachusetts authorities in the summer of 1722. Nevertheless, the Courant’s fame spread, and it continued to publish Silence Dogood’s missives as young Benjamin took over the day-to-day operations of the newspaper while his brother was jailed. Franklin credited the experiences of 1722 with introducing him to some of the most important work and many of the themes of his adult life—writing for an appreciative audience, courting the ire of both clerical and legal authorities, publishing a newspaper, and because of his brother James’s “harsh and tyrannical Treatment,” inculcating in him an “Aversion to arbitrary Power that has stuck to me thro’ my whole Life.”

As many Franklin scholars have noted, his decision to write in the voice of Silence Dogood was clever and perceptive. By taking on the identity of a woman named “Silence,” he underscored the absence of authority he had as a social critic in a world where outspoken women were punished for their pride, and post-menopausal women in particular were either ignored, demonized, or praised for their piety in tedious funeral sermons published only when their silence was absolutely assured. But by choosing to write as an older widow, he appropriated the voice of an old Gossip whose opinions might nevertheless be credited by her neighbors and acquaintances because of her age and experience. Furthermore, his choice of surname was an obvious mockery of Cotton Mather’s Bonifacius: or Essays to Do Good (1706). The son and grandson of legendary puritan divines and so prolific a writer as to be a one-man full employment scheme for the printers of Boston, Mather was the face and relentless voice of the puritan establishment in early eighteenth-century Boston. But the teenaged Franklin knew that Mather was getting older—a living relic of the last century, he was pushing sixty in 1722 and had been badly bruised the previous year by a vicious public controversy over his advocacy for smallpox inoculation. Satirizing his worldview in the voice of an old widow made Silence Dogood the rough equal of Mather—a shocking inversion of Mather’s view of himself and patriarchal puritan society.

Franklin’s Silence Dogood essays are a tribute to a centuries-old teenage wit that remains fresh and perceptive. His first essay opened with a comment about the importance that the reading audience places on the station and reputation of writers:

The generality of people now a days, are unwilling either to commend or dispraise what they read, until they are in some measure informed who or what the Author of it is, whether he be poor or rich, old or young, a Schollar or a Leather Apron Man, &c. and give their Opinion of the Performance, according to the Knowledge which they have of the Author’s Circumstances.

Franklin recognized that choosing pseudonymity instead of anonymity and creating a colorful backstory for Silence Dogood made for more interesting and more colorful writing, besides satisfying a reader’s desire “to judge whether or no my Lucubrations are worth . . . reading.” Dogood tells us in this first essay that she was a poor, fatherless, seaborn child who, as it happens, shared Franklin’s zest for self-improvement and upward mobility. In the second Dogood essay, we learn that she entered service to a “Reverend Master” who had never married. Dogood turned his head and by and by, dear reader—he married her. Franklin’s portrait of Dogood’s sexually ambitious youth was a beam in the eye of the senior generation of puritan ministers. Could a sixteen-year-old apprentice get away with that in printer’s ink? Probably not—but an imaginary widow just might be able to pull it off.

Franklin is notable in American letters as a writer who more often than not published his work under pseudonyms. The great game of Franklin scholars for nearly 200 years has been attributing yet another pseudonymously published work to him—but as James N. Green and Peter Stallybrass note in Benjamin Franklin: Writer and Printer, “the danger of this enterprise is that it obscures the lengths to which Franklin went to erase authorship.” I would add that a brief survey of some of the pseudonyms attributed to Franklin show a real commitment to writing in women’s voices. Besides Dogood, he also wrote as “Ephraim Censorius, Margaret Aftercast, Martha Careful, Caelia Shortface, the Busy-Body . . . Patience, the Casuist, the Anti-Casuist, Anthony Afterwit, Celia Single,” and of course, Richard Saunders and Poor Richard, among many others. This mixture of feminine, masculine, and androgynous pseudonyms is typical of his choice of pseudonyms through his publishing career.

Other writers for Common-place have noted in years past that the modern political and academic blogospheres resemble nothing so much as the world of journal writing and print culture in the antebellum era. W. Caleb McDaniel wrote in 2006 about how in reading the journals of reformer Henry Clarke Wright (1797-1870), he concluded that Wright “shared several traits with the prototypical blogger—his eccentric range of interests, his resolution ‘to write down what I see and hear and feel daily,’ his use of journals to ‘let off’ rants of ‘indignation,’ his utopian conviction that writing might change the world, and (not least) his practice of spending the ‘greater part of the day writing in his room,'” something that might sound familiar to a lot of bloggers. In 2007, Meredith L. McGill wrote optimistically about the spirited writing she finds on self-published blogs and of blogging’s potential to destabilize the authority of modern print culture. However, she also noted that the absence of any code of ethics or standards among bloggers can undermine the credibility of the enterprise. For example, McGill notes that blogs have “suffered from the accusation that their much-vaunted inclusion of diverse sources and of voices is a sham made possible by pseudonymity,” which may be employed by both bloggers and their commenters alike. She also quotes Charles Dickens’ complaint about the absence of redress when magazine and newspaper editors decided to reprint his stories. The author, he said, “not only gets nothing for his labors, though they are diffused all over this enormous Continent, but cannot even choose his company. Any wretched halfpenny newspaper can print him at its pleasure—place him side-by-side with productions which disgust his common sense.”

Clearly, the roots of the boisterous and frequently libelous print culture in the Early Republic and antebellum eras were planted deep in the eighteenth century with the birth of newspapers and magazines. In eighteenth-century newspapers, there was no clear and stable distinction between fact and fiction in the varied articles that might be written afresh, ripped off from other newspapers, or reconfigured for a local audience. Eighteenth-century British and U.S. copyright laws covered only books—newspapers and magazines were exempt from copyright laws, which may explain the jumble of frequently borrowed news and refashioned entertainments found in early American newspapers. Publishers like James Franklin, like many proprietors of Websites and news aggregators today, were just looking for content. He felt no ethical obligation to verify the identity of Silence Dogood or any of the other anonymous or pseudonymous writers he published.

Many users of the Internet see a great deal of value in pseudonymity, and use it variously both in blogging and commenting on blogs. As McGill wrote in these pages four years ago, “[b]loggers’ willingness to risk the credibility of their medium in order to retain the pseudonymity that fuels the expansion of the blogosphere should tell us something about the importance of concealed identities to the history of authorship.” The blog that probably makes the greatest use of pseudonymity in the great American literary tradition is Roxie’s World, a blog by University of Maryland English Professor Marilee Lindmann. Roxie’s World, like Historiann, is only lightly pseudonymous. “Roxie” is a dead dog—Lindmann’s late wire-haired retriever—and the blog is written in her voice via her “typist” named Moose (Lindemann.) Lindemann (as Moose channeling Roxie) blogs about nineteenth-century American literature while playing with different pseudonyms, voices, and literary conventions. Emily Dickinson and Willa Cather are regular subjects at Roxie’s World, and because this is a blog that channels the afterlife, that great pseudonymous American writer Mark Twain appears occasionally to have a few drinks at a fictitious local pub called “Ishmael’s” and talk things over with Roxie and her typist Moose.

So why do so many academic bloggers blog pseudonymously? Like Franklin, they adopt pseudonyms because they can publish things that they otherwise couldn’t publish under their own names. There are some bloggers for whom pseudonymity is not only preferable, it may have been the only prudent choice. For example, GayProf, who blogs at Center of Gravitas, has written extensively about being a gay academic and his painful breakup with a boyfriend, in addition to writing about American Studies and Latino history in the U.S. Other bloggers like Dr. Crazy and medieval European historian Squadratomagico have written about their professional lives in ways that would be awkward or indiscreet if they wrote frankly about departmental politics or problems with students under their real life identities. I’m sometimes envious of the range of issues pseudonymous bloggers can address, and the specific and personal ways they can address them precisely because of their pseudonymity. Because I’m not fully pseudonymous, I don’t write about students or problems in my department. As I wrote last year, for me to do so would seem “at the very least disloyal, if not predatory.” I’m sure there are academic blogs that use pseudonymity as a weapon—but I don’t read them. Bloggers who merely complain about something or someone don’t have very interesting blogs, nor do I think they acquire or sustain a wide readership. Contrary to Silence Dogood’s prankish observations, “the generality of people now a days”—at least those who read blogs—recognize thoughtful writing and interesting ideas whatever their provenance.

Pseudonymity can work in the service of community-building in the blogosphere. As I’ve noted earlier, although I often criticize public figures and many of the features of academic and American life, I’ve tried to build a community of readers and commenters who can share stories and information and perhaps use that knowledge to their own benefit. Although I’m not fully pseudonymous, my commenters are overwhelmingly pseudonymous. Nevertheless, regular readers and commenters probably recognize the commenters who appear most frequently because most of them have individual personality traits or interests that remain fairly stable. That is, they fully inhabit the names or roles they’ve chosen to play on my blog, and their pseudonymity, as well as the role I play as Historiann, is key to the kind of supportive community I wanted to build.

One example of a blogger and commenters working together in community-building is the occasional feature I run in which a reader asks for the advice of the community of readers at large. I’ve given lots of unsolicited advice in blog posts, and strangely unlike real life, that has led to more and more readers sending me e-mails asking for help with various academic career problems. (To be clear: they’re not usually asking for my personal advice, but rather for the advice of my other readers and commenters!) So, I occasionally run “Agony Aunt”-type letters that seek help from my readers on a variety of issues: applying to graduate school, the academic job market, strategies for winning tenure, two-body/family issues in academic careers, and ideas for protecting their careers in the face of unfair treatment or even harassment. In these cases, I make use of pseudonymity or anonymity in the service of helping these readers—for example, “Hotshot Harry from Tucumcari,” “Tenured Tammy,” “Busted Barry,” and “Demoralized Debby” have all made appearances on the blog—and sometimes they join in the discussion in the comments about their problems.

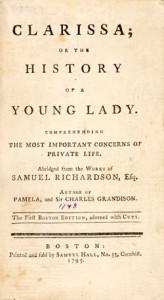

Only once has publishing pseudonymous or anonymous commentary on someone’s problems been even slightly controversial with my commenters. The one case I can think of provides an instructive example on a number of levels of both the uses and problems with pseudonymity and online conversations—and interestingly, includes allusions to eighteenth-century literature. Last spring, I ran a lengthy narrative by “Anonymous, an Assistant Professor in the Humanities” describing her frustrating attempts to get a maternity leave from her department. You’ll have to read the whole thing, but the long and short of it is her concluding line: “This experience can be safely filed under the heading ‘How to Alienate/Get Rid of Your Female Faculty.'” Anonymous was a reader who sent me an unsolicited e-mail about this—she was and is not known to me personally. I did not identify her university or department in any way, and before I published her story, I asked her to send me an e-mail from her institutional address so that I could verify as far as I could that her story was on the level. (At least, I could verify that she’s a real person in a real academic department.) A (presumably pseudonymous) commenter “clarissa” wrote that “something about this narrative . . . just doesn’t add up. . . The fact that her chair and dean are depicted as so clueless, malicious and out of touch adds just the right element of melodrama and, honestly, strains my credulity.” Ze commented later that Anonymous should read her faculty manual and take care of business rather than complaining anonymously on a blog: “[S]he uses the tropes of melodrama (poor young pregnant assistant professor being done wrong by villainous, likely mustachioed, administrators) and rather than acting, writes an anonymous blog post hoping that the sisterhood will save her.”

There’s a lot that we don’t know, and that even I don’t know about this exchange. “clarissa” might be entirely correct—after all, I don’t know Anonymous, and even if I did, I wasn’t privy to her conversations with her Chair or his exchanges with the Dean. Ze also makes a good point about the narrative conventions that Anonymous uses (wittingly or not) of an innocent young woman victimized by bad men. I presume that’s why the commenter chose the pseudonym “clarissa,” after Samuel Richardson’s 1748 novel about female virtue lost, Clarissa, or, the History of a Young Lady. (I didn’t see quite the same narrative conventions at work in Anonymous’s tale—I thought the department Chair looked inept and willfully clueless rather than evil, and I thought that Anonymous’s description of her assertive actions set her far apart from Clarissa Harlowe, but to each her own.) Here’s what I know, or think I know: the real life identity of Anonymous. I know where she teaches, and I know that lying about this kind of thing in a community of feminist academics is a really bad idea, especially when the blogger knows your name. I don’t know who “clarissa” is at all—the commenter left what appears to be an easily traceable academic e-mail address in the comment form that only I can see, but I can’t assume that the possessor of that e-mail address is “clarissa.” After all, the e-mail addresses of most faculty in the U.S. are easily located in a Google search and two or three clicks—so anyone can copy someone else’s e-mail address into the comments form on my blog.

There are 74 comments on that post—and a lot more ugly and annoying stories about U.S. academia’s continuing failure to acknowledge that there are now women on the faculty as well as on the staff. Overall that post was productive—a community of readers responded with their own struggles over their maternity leaves, and many (including Anonymous) commented about how helpful the resulting conversation was for them. That’s the best that blogs can do for their readers—make connections across geographies and time zones and create a community in which we can have conversations about things that aren’t covered in big media formats, and offer deeper conversations about issues that even academic publications like The Chronicle of Higher Education and Inside Higher Ed can cover only glancingly. Pseudonymity is an important tool for helping those conversations happen, especially when it comes to opening up these conversations to those who don’t have their hands on the levers of power and who aren’t protected by tenure—probational regular faculty, contingent faculty, and students. (You know—the majority of people in the academic workplace, whose silence is coerced by their relative powerlessness.) Like Silence Dogood and her inventor, the young Franklin, they’re expected to perform their labors without complaint.

Silence Dogood did well for the Courant by her silence. In fact, it was Franklin who outed himself as the author, perhaps because he couldn’t stand to hear others praising the trenchant wit of Silence Dogood instead of Benjamin Franklin. He explained that “I kept my Secret till my small Fund of Sense for such Performances was pretty well exhausted, and then I discovered it.” (He was, after all, only sixteen—and couldn’t yet imagine fully everything Silence Dogood might have learned in her lifetime.) Franklin writes that his brother James “thought, probably with reason, that [praise for the essays] tended to make me too vain,” and suggests that James’s resentment of Franklin’s pseudonymous success precipitated Franklin’s decision to escape his brother’s thrall, and Boston too, to go on to become one of America’s great newspapermen, humorists, inventors, autobiographers, and statesmen.

As a blogger, I can identify with Franklin’s statement that he sustained the Silence Dogood letters only “till my small Fund of Sense for such Performances was pretty well exhausted.” I don’t want to think about blogging into the void after I have nothing of real value left to offer my readers. But I’m closer in age and stage in life to Silence Dogood now than to the young Franklin, and this ain’t my first time at the rodeo. So I’ll continue blogging so long as my “small Fund of Sense” holds out, the readers keep showing up, and the creek don’t rise and wash out my Internet connection, anyway.

Further reading:

On Franklin and his early career as a writer, see Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, edited by Leonard W. Labaree (New Haven, Conn., 1964); David Waldstreicher, Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution (New York, 2004); James N. Green and Peter Stallybrass, Benjamin Franklin: Writer and Printer (New Castle, Del., 2006); and J. A. Leo Lemay, The Life of Benjamin Franklin, volume I: Journalist, 1706-1730 (Philadelphia, 2006). Albert Furtwangler addresses the “Silence Dogood” letters in detail as well in “Franklin’s Authorship and the Spectator,” New England Quarterly 52:3 (1979), 377-96. Meredith McGill’s essay “Copyright,” in A History of the Book in America, volume 2, An Extensive Republic: Print, Culture, and Society in the New Nation, 1790-1840, eds. Robert A. Gross and Mary E. Kelley (Chapel Hill, 2010), 198-211, is invaluable for understanding early American copyright law.

For more context on the man Silence Dogood’s letters mocked, see Kenneth Silverman’s definitive biography, The Life and Times of Cotton Mather (New York, 1985). On the Boston smallpox epidemic and inoculation controversy, see Robert V. Wells, “A Tale of Two Cities: Epidemics and the Rituals of Death in Eighteenth-Century Boston and Philadelphia,” in Mortal Remains: Death in Early America, eds. Nancy Isenberg and Andrew Burstein (Philadelphia, 2003), 56-67; and Margot Minardi, “The Boston Inoculation Controversy of 1721-1722: An Incident in the History of Race,” William and Mary Quarterly 61:1 (2004), 47-76.

On pseudonymity among bloggers and commenters, see Dr. Crazy, “A Compendium of Posts about Blogging under a Pseudonym,” Reassigned Time (http://reassignedtime.blogspot.com/2009/06/compendium-of-posts-about-blogging.html,) accessed November 16, 2010. I have written about gender, authority, and online personae in Ann M. Little, “We’re all Cowgirls Now,”Journal of Women’s History 22:4 (2010).

The author would like to thank T.J. Tomlin and Mark Peterson for their helpful comments and suggestions on an earlier draft of this essay.

This article originally appeared in issue 11.2 (January, 2011).