Disease permanently robbed Oliver Shaw of his sight as a youth. But instead of despairing about his damaged eyes, Shaw (1779-1848), who made his adult life on Westminster Street in Providence, Rhode Island, cultivated his ear. He became an esteemed pianist, church organist, and music teacher, as well as a modestly prolific composer of hymns, marches, and waltzes. Local sites and historical events of Rhode Island and southeastern New England frequently inspired him, along with his son, Oliver J. Shaw (ca. 1813-1861), who followed in his father’s footsteps to a thriving career as a musician. In 1840, one of the Shaws—likely the younger—published a curious composition titled Metacom’s Grand March. It was dedicated to John W. Dearth of Bristol, Rhode Island, the colonial settlement established on the very homegrounds of the Pokanoket-Wampanoag sachem Metacom, or King Philip. Philip was one of the most influential Eastern Algonquian leaders of the late seventeenth century. He was also the namesake of the conflict known as King Philip’s War, which seared New England and the Native Northeast between 1675 and 1678. The war destroyed English settlements, roused anti-Indian fears among colonists, and decimated or dispersed countless tribal peoples, who were attempting to maintain their landholdings, political autonomy, and cultural distinctiveness amidst rising tides of English settler colonialism. Philip’s homegrounds in upper Narragansett Bay lay at the geographic epicenter of the violence, and it was on the mountainside that Philip died following pursuit in August 1676.

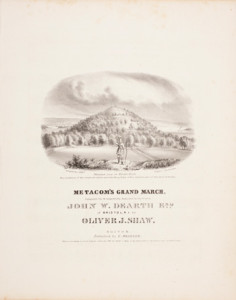

By the time Shaw took up the war and its landscape as musical subjects, Philip and Mount Hope figured very differently in Euro-American imaginations than they had nearly two centuries earlier. No longer was Philip a treasonous, despicable heathen, as he had appeared in the 1670s to his English antagonists. (They thought him so “Blasphemous,” Jill Lepore argued in The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity, that Cotton Mather posthumously silenced him by ripping the jawbone off his skull.) Nor was his Mount a forbidding, swampy wilderness resistant to colonial presence. Shaw romanticized Philip, heroically elevating him to martial stature in the formal strains of his Grand March. If the composition’s title did not convey adequate meaning, the accompanying illustration on the sheet music’s cover clarified the message (fig. 1). It showed a picturesque western view of Mount Hope, depicted as a conically shaped hill partially denuded of trees, crisscrossed by roads or walls, and topped by a tiny structure. In front of it posed “the renowned Indian warrior King Philip.” This stylized Philip confidently brandished a large bow, while reaching back into his quiver for an arrow.

How Philip came to figure in the Grand March involves a story of music’s complex intertwining with memory in colonial contexts. Music played an important role in Native/settler encounters of early America, as well as in the remembrance of cross-cultural violence. As a crucial turning point in the region commonly called New England, King Philip’s War has persisted in collective memories for more than three centuries, haunting tribal as well as settler imaginations and understandings of history. Memory—slippery to define, but characterized here as the usable forms of the past handed down to posterity—is frequently a collective enterprise, involving group rituals and performances. Aural elements animated many of these activities: war chants, mourning laments, victory songs, and folk ballads. Metacom’s Grand March exemplified one strain of commemorative musicality: genteel, even nostalgic colonial appropriations that played off notions of the noble savage or fearsome foe, and claimed Philip as a regional founding figure.

But the Northeastern soundscape was never wholly controlled by Euro-Americans. Counter-traditions of indigenous musicality associated with the war and its aftermath also endured, affirming indigenous continuity, presence, and power in a region too typically represented as devoid of Native peoples following the colonial “Indian Wars.” By tracing a range of metamorphoses in music connected to King Philip’s War, we can see how unstable memories of these events became over the centuries, adjusting in response to changing social circumstances and musical trends. We can also better understand how intensely localized commemorative sensibilities could be. For many composers and performers inspired by King Philip, their attentions were less beholden to national (“American”) articulations of identity, and more so to the minor, even parochial, concerns of particular towns, regions, and tribes.

Additionally, while the mid-nineteenth century brought a flowering of musical treatments of Philip, it is important to contextualize this period within a longer sweep of time. Native and colonial peoples all cultivated distinctive forms of music-making prior to the crisis of the 1670s, while in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, Algonquian communities and their music have undergone noteworthy revivals. Recent mainstream revisitations of the war’s meanings have also used music as a tool for re-centering indigenous practices conventionally marginalized by popular interpreters. Taken together, these multi-generational developments demonstrate how people of the Northeast and beyond have persistently turned to music as a way of confronting—or skirting around—an intensely contested watershed in early American history.

Well before conflict with the English broke out around Mount Hope in summer 1675, Algonquians’ ceremonies and everyday life incorporated music in key ways. At nighttime, lying side-by-side in wetus, Algonquians would “sing themselves asleep.” Powwows, or shamans, sang as they practiced rituals, prayer, and medicine, sometimes with onlookers joining in “like a Quire.” Nipmucs “delight much in their dancings and revellings,” Daniel Gookin observed about a community gifting celebration: “at which time he that danceth (for they dance singly, the men, and not the women, the rest singing, which is their chief musick) will give away in his frolick, all that ever he hath,” an event akin to Narragansetts’ Nickómmo feasts/dances. To send deceased relations to the afterlife, some communities buried tiny brass bells with their dead, possibly used in rattles, jingles, or other sound-making items.

To mourn their relations, Narragansetts undertook structured rituals of vocalizing grief: “blacking and lamenting they observe in most dolefull manner, divers weekes and moneths”; “morning and evening and sometimes in the night they bewaile their lost husbands, wives, children brethren or sisters &c.” What, exactly, this “lamenting” consisted of Roger Williams did not specify in his Narragansett/English lexicon, A Key into the Language of America (1643). Nor did other English observers record fine-grained notations of Algonquians’ musical practices. But their indirect commentaries, along with material traces recovered by archaeologists, attest to a rich aural milieu intertwined with tribal cosmologies and lifeways. This music was functional, not simply aesthetically or sonically experimental. Algonquians used music as a conduit to sources of power, and as a community-building mechanism that connected the living to a multitude of animals, plants, landforms, and an ancient community of ancestors.

Sustained contact with European settlers transformed some Algonquian musical traditions. In the Praying Towns established in the mid-seventeenth century, psalm-singing in the Massachusett dialect served as a critical technique of religious and cultural conversion. But despite some early optimism about cross-cultural interactions, tensions between tribes and colonial authorities in Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, Rhode Island, and Connecticut escalated at mid-century. Settlers grew wary of certain Algonquian behaviors, including community gatherings and their accompanying sounds. The English were particularly suspicious of dances, which were important rituals in the prelude to war as tribal parties engaged in diplomacy and felt out each other’s intentions for alliances. The brash Plymouth colonist and military ranger Benjamin Church attended one such event hosted by Awashonks, the sunksquaw, or female leader, of Wampanoags located at Sakonnet, east of Narragansett Bay. In his postwar memoir (a freewheeling account that trafficked loosely in facts), Church remembered how he and Charles Hazelton “rode down to the place appointed, where they found hundreds of Indians gathered together from all parts of her dominion. Awashonks herself in a foaming sweat, was leading the dance.” Such dances, he wrote, were “the custom of that nation when they advise about momentous affairs.”

Following the war’s outbreak, colonial soldiers and Native war-parties grappled for control of territory, and sound played a critical role for both as a medium of communication. English troops took horns into combat to signal to each other, for instance. Rumor had it that the sounding of a trumpet “without order, did much hurt” on one campaign, though evidently the metallic blast carried poorly in the woods. When Mohegans allied with the English dismembered a Narragansett captive, they inflicted pain while “making him danceround the Circle, and sing, till he had wearied both himself and them.” This allowed the captive to preserve honor by displaying mettle in the face of certain death. For English captives removed from their homes and thrust into unfamiliar surroundings, Algonquian music-making heightened the sense of dislocation. Mary Rowlandson vividly described a Native attack on Lancaster, Massachusetts, in February 1676, in which part of the trauma was visual: “It is a solemn sight to see so many Christians lying in their blood, some here, and some there, like a company of Sheep torn by Wolves.” But as she elaborated in The Sovereignty and Goodness of God (1682), she also felt distressed by boisterous vocalizations of the Natives, who were “roaring, singing, ranting and insulting, as if they would have torn our very hearts out.”

The first night of her captivity, Rowlandson was taken up a hill within sight of the smoldering town. She recalled the spectacle: “Oh the roaring, and singing and danceing, and yelling of those black creatures in the night, which made the place a lively resemblance of hell.” The “joyfull” Natives feasted on slaughtered sheep, calves, pigs, and fowl. After that she “removed” west into a “vast and desolate Wilderness”—well-known homelands to Algonquians—and periodically heard loud celebrations among victorious Natives returning from offensives:

Oh! the outragious roaring and hooping that there was: They began their din about a mile before they came to us. By their noise and hooping they signified how many they had destroyed …Those that were with us at home, were gathered together as soon as they heard the hooping, and every time that the other went over their number, those at home gave a shout, that the very Earth rung again… Oh, the hideous insulting and triumphing that there was over some Englishmens scalps that they had taken.

These songs and exclamations, which struck Rowlandson as “noise” rather than tonally, symbolically sophisticated communication, would have sounded noticeably different from the austere singing done by New England Puritans in worship.

King Philip’s War caused massive casualties among Algonquian communities through direct assaults, as well as starvation and cold as tribal peoples were forced away from resources of their customary homelands. Algonquians’ complex rituals for dealing with death likely changed under the exigencies of wartime. The massacre at Great Swamp in December 1675, and the equally devastating massacre at the waterfalls of Peskeomskut in May 1676, made traditional practices of mourning difficult. Native survivors fled the scenes to seek refuge in other places and regroup, since it was risky to remain and inter the bodies of their fallen relations in the usual ways. Perhaps they engaged in “lamenting” and associated forms of grieving in their diasporic locations. It is also possible that Native peoples who survived, and their descendants, managed to return to these sites of devastation to mourn, despite territorial dispossessions and growing colonial restrictions on Native mobility. In a tantalizing shard of “tradition,” a “gentleman” owning land at Mount Hope reported “he remember[ed] a squaw, formerly belonging to Philip’s family, who lived to extreme old age, and annually repaired to the Mount, to weep over the place where he was slain.” Published in the Massachusetts Magazine (1789), this account may have been invented. Or it may have been evidence of ongoing Wampanoag connections to that landscape and its unsettled past.

“Indian Wars” raged in the Northeast for decades after the formal closure of King Philip’s War, in conflicts that drew northern French and Wabanaki communities into strife with New Englanders. English men, women, and children taken captive found themselves drawn into Native orbits, and during their forced sojourns, they heard astonishing new music. John Gyles was taken in 1689 from Pemaquid in mid-coastal Maine to a Wabanaki settlement at Madawamkee, where he encountered this: “a Number of Squaws got together in a Circle dancing and yelling.” He found himself pulled into the ring, until his “Indian Master presently laid down a Pledge and releas’d [him].” Gyles maintained ethnographic curiosity about the Natives with whom he lived, and documented other instances of singing during his time among Wabanakis. To express gratitude for a successful bear hunt, for example, a female elder and captive “must stand without the Wigwam, shaking their Hands and Body as in a Dance: and singing, WEGAGE OH NELO WOH! which if Englished would be, Fat is my eating. This is to signify their thankfulness in feasting Times!” As war fostered uneasy intimacies among captives and captors, these settlers observed selected dimensions of Algonquian cultures that otherwise would have remained beyond their circles of seeing—and hearing.

One intriguing account of Algonquian singing from this later period arose from the repercussions of King Philip’s War. At Cocheco (Dover, New Hampshire), the trader and military leader Richard Waldron had hundreds of “strange” Indians, refugees from the war’s southern theater, seized during a “sham fight” staged in September 1676. It was an act of betrayal that sat poorly with the neutral or “friendly” local Algonquians who remained. In 1689, during the early stages of King William’s War, Native forces struck back at Waldron in retaliation for this and other grievances. Two Native women infiltrated the settlement to open its doors for nighttime attackers. According to tradition, one of those women sang an ominous song to the over-confident Waldron. It may have warned him of the imminent violence, or perhaps mocked him with cryptic verse:

O Major Waldo,

You great Sagamore,

O what will you do,

Indians at your door!

But heedless of her singing, the garrison and Waldron himself fell as Natives attempted to push back the colonial frontier.

As the eighteenth century progressed, violent Native/settler confrontations tapered off in southern New England. Some colonists preferred to forget the area’s blood-soaked past and focus on the future. But others decided to commemorate ancestral losses in public ways. Perhaps people sang at Sudbury, in eastern Massachusetts, in the 1730s when Benjamin Wadsworth, president of Harvard College, installed a stone memorial to his father. Captain Samuel Wadsworth and troops had been killed there in an engagement with Natives in April 1676. President Wadsworth’s diary is silent about the proceedings, unfortunately. Overall, eighteenth-century colonial commemorations of the war are somewhat elusive in the archives, especially at the level of “folk” practices. (The original Sudbury memorial stone and a larger, nineteenth-century monument presently stand in a town cemetery that has hosted Memorial Day commemorations, accompanied by singing and drumming related to King Philip’s and subsequent wars.)

By the early years of the American republic, colonial violence became fodder for more formalized Yankee commemorations of local, regional, and national heritage. In 1835, residents of South Deerfield, Massachusetts, and surrounding towns decided to erect a monument at “Bloody Brook” to honor colonial troops killed in King Philip’s War. Thomas Lathrop and his company of North Shore militiamen (the “Flower of Essex”) fell to a Native ambush in the Connecticut River Valley in September 1675. That loss loomed large in settler imaginations thereafter. The commemoration was an enormous spectacle, said to attract 6,000 visitors. A choir and band performed, and several “original hymns” specially composed for the occasion solemnized the proceedings, which culminated in the laying of a cornerstone for an obelisk. In a major coup for the small town, organizers secured the presence of politician Edward Everett. He delivered a rousing oration commemorating colonial sacrifices, while briefly mourning the supposed vanishing of Indians from the valley.

Harriet Martineau chanced to be traveling through the area at the time. The sharp-eyed British commentator dissected the proceedings with an acid tongue, and published the critique in Society in America. The theatrics left her unimpressed, including the band’s musical efforts: “They did their best; and, if no one of their instruments could reach the second note of the German Hymn, (the second note of three lines out of four,) it was not for want of trying.” The ensuing oration “deeply disgusted” her. So did an amateur painting of the ambush exhibited in the Bloody Brook Inn. Overall, Martineau found the Bloody Brook commemoration a grotesque spectacle, involving inept folk performances and shameless electioneering by politicians angling for the western Massachusetts vote.

Martineau’s dyspeptic analyses notwithstanding, Yankees tended to revel in these grassroots commemorations of Anglo-American ancestors and the colonial past. Decades after the installation of the cornerstone, Everett’s nephew Edward Everett Hale composed “The Lamentable Ballad of Bloody Brook,” presented in 1888. Though the piece evidently was read aloud rather than being set to music, the “Ballad” invoked the genre of folkloric songs to give New England a distinctive piece of mythology. Its lines elevated colonial casualties to martyred stature:

Oh, weep, ye Maids of Essex, for the Lads who have died,—

The Flower of Essex they!

The Bloody Brook still ripples by the black Mountain-side,

But never shall they come again to see the ocean-tide,

And never shall the Bridegroom return to his Bride,

From that dark and cruel Day.—cruel Day!

The antebellum period proved a popular moment for revisiting the meanings of King Philip and the colonial period more generally. It was an era when the six-canto poem Yamoyden: A Tale of the Wars of King Philip (1820) appeared, and when James Fenimore Cooper published a frontier romance based on the war, titled The Wept of Wish-Ton-Wish (1829). In 1833, orator Rufus Choate urged New Englanders to develop romantic mythology about their own regional past, holding up King Philip’s War as an ideal subject. Not only literary luminaries found romantic inspiration in Philip. Musicians also tapped into this growing popular fascination, in compositions like Metacom’s Grand March. Oliver J. Shaw’s 1840 piece—to be performedcon spirito—was part of a “grand march” genre that included other martial-themed compositions, to be performed with gravity and ceremonial pomp. This stylistic choice indicated that Shaw’s work was honoring Philip as a worthy leader, rather than lampooning him or denigrating him as a mere “savage.”

Shaw’s Grand March was generic in one sense, invoking notions of Indian nobility and exoticism circulating in American consciousness at a national level. But it also responded to local topography and traditions. Shaw intimately knew the environs of Providence and Rhode Island, along with neighboring corners of southeastern Massachusetts, and Mount Hope was undoubtedly familiar terrain. He dedicated the piece to John W. Dearth, Esq. of Bristol, whom he may have known through common interests. (Dearth was identified as a “teacher of music” in the 1870 census.) Bristol in 1840 was thoroughly colonized terrain, having been claimed by English settlers soon after the conclusion of King Philip’s War and developed as a seaport and village. The grounds were thus formally removed from Wampanoag land-holdings, although Natives labored as servants/slaves in colonial households, and may have continued to travel along the peninsula and Mount. Later in the nineteenth century, members of the Rhode Island Historical Society made pilgrimages en masse to Mount Hope for commemorative festivities, with particular energy around the bicentenary of King Philip’s War, ca. 1876. These antiquarians also installed monuments marking Philip’s “Seat” and the alleged spot of his death. But it is not apparent that such prominent events were underway when Shaw developed his composition, or if his source of inspiration lay elsewhere. Whether anyone ever performed the Grand March for an audience is also unknown at present—either in its original instrumentation (possibly for band), or in the arrangement for piano. The piece may have attained renown in local circles. Or it may have languished unheard, the musical token of one composer’s affection for a place, a past, and a friend.

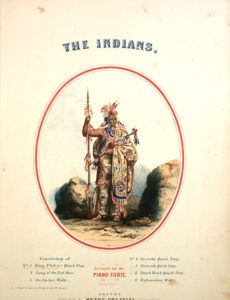

Shaw was not alone in taking King Philip as a muse in the antebellum period. “King Philip’s Quick-Step” (fig. 2) was piece No. 1 in a collection titled The Indians (1843), arranged by Simon Knaebel for piano. Published by Henry Prentiss in Boston, its front page bore a gaudy chromolithograph of an Indian draped in Plains-style regalia, carrying a spear in his right hand. The “Quick-Step” was more upbeat than the Grand March, and the collection contained other pieces on comparable themes: “Song of the Red Man,” “On-Ka-Hye Waltz,” “Osceola Quick Step,” “Keokuck Quick Step,” “Black Hawk Quick Step,” “Nahmeokee Waltz.” This final waltz referenced the fictional female Indian featured in John Augustus Stone’s wildly popular nineteenth-century play Metamora; or, the Last of the Wampanoags, a romanticized theatrical treatment of King Philip’s War. In its final scene, Metamora stabs Nahmeokee to death to spare his wife from capture by the English, then falls to English fire. Drums and trumpets sounded as the curtains closed.

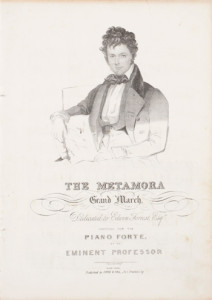

The play’s star, the charismatic actor Edwin Forrest, received a musical tribute in the form of The Metamora Grand March, published in New York in 1840 and dedicated to him. Composed by an anonymous “eminent professor” and arranged for piano (D-major, 4/4), this Grand March directed the pianist to perform in a Marziale manner (fig. 3). The sheet music featured on its cover the elegantly suited Forrest posing in a chair. It memorialized not the original historical Metacom, as Shaw’s march did, but instead the celebrated white performer many degrees removed. The Grand March conceivably could have been played during one of the numerous showings of Metamora. (A Philadelphia performance of 1863, for instance, promised that an orchestra under Mark Hassler would play “a Selection of the most Popular and Classical Music.”) Many pieces from this period approached King Philip’s War with a degree of regret for a tragic past, albeit a dramatic one; and with unease about losses caused by colonial “conquest”—sentiments at an apex during the hotly contested Indian removals of the Jacksonian age, which New Englanders were eager to critique even as they sidestepped Native struggles on their own doorsteps. But such pieces showed more interest in the idea of Indians than in actual, contemporary indigenous people.

Native Americans had not disappeared, despite Euro-American tendencies to write them off as a doomed race. Those who remained were capable of musically mobilizing King Philip for their own ends in the same period. Thomas Commuck (1805-55), who self-identified as Narragansett, removed from the New England region to the Brothertown community of Christianized Indians, and in 1845 he co-produced a hymnal that incorporated a profusion of Algonquian names. (Thomas Hastings did the harmonizations.) Among the names were individuals and locations prominent in King Philip’s War and the Native Northeast: Sassamon, Wetamoe, Annawon, Pocasset, Assawomset, Seconet, Pokanoket, Tispaquin, Philip. “This has been done merely as a tribute of respect to the memory of some tribes that are now nearly if not quite extinct; also as a mark of courtesy to some tribes with whom the author is acquainted,” Commuck explained in the preface to Indian Melodies (fig. 4). The handful of direct references to Narragansett heritage (like hymns titled “Canonchet” and “Netop”) formed pieces of a multi-tribal mosaic, fittingly emblematic of the composite community at Brothertown.

The names did not appear to bear any particular relation to the content of the hymns, however, some of which derived from the well-known Isaac Watts. Indeed, the earnest expressions of Protestant faith would have been at odds with many figures’ anti-colonial stances. But they were not entirely dissimilar from other Native Christian worship music of the time (following the “Indian Great Awakening” of the mid-eighteenth century), and they signaled admiration for the real historical figures referenced. Commuck’s goal in publishing the hymnal was not strictly memorial. He also hoped to

make a little money, whereby he may be enabled, by wise and prudent management, to provide for the comfortable subsistence of his household, and be enabled, from time to time, to cast in his mite to aid in relieving the wants and distresses of the poor and needy, and to spread the knowledge of the Redeemer and his kingdom throughout the world.

Here, King Philip had been re-purposed to support Christian charitable works by members of an Algonquian diaspora. Though separated from ancestral homelands, they committed themselves to fashioning a new, viable Indian community in the west.

Yankee musical tastes morphed in the latter nineteenth century, decades that brought major political and territorial blows to contemporary Algonquians. The state of Rhode Island illegally “detribalized” the Narragansetts in the 1880s, for example, and auctioned off tribal lands. Yet cultural fascination with historicNatives persisted. During the colonial revival’s burgeoning interest in Anglo-American heritage, casts of hundreds, even thousands, converged on town greens and in performance halls to enact the founding scenes of local history in pageants. All the while, they excised indigenous presence from the narratives, or relegated it to stock formulations. In Rehoboth, Massachusetts, Anawan Rock Pageant; or, The Atonement of Anawan: A Tercentenary Drama from the Indian Point of View dramatized the exploits and ultimate capitulation of Anawan, one of Philip’s advisors. Rehoboth laid claim to an enormous geologic feature said to be the site of Anawan’s 1676 capture, and the 1921 pageant spun its theatrics around it. Henry Oxnard designed the five-part drama for use in churches and granges. Performed at an energetic clip, the whole could be presented in under fifty minutes. Or it could be lengthened by inserting music between the parts.

Stage directions suggested the use of “Patriotic and Indian songs.” They helpfully provided a laundry list of popular tunes with zero connection to the war, but ample familiarity to the audience:

O, Columbia, Gem of the Ocean,

John Brown’s Body,

Battle Hymn of the Republic,

Juanita,

The Breaking Waves Dashed High,

America,

Katherine Lee Bates’ America, to the tune of Materna

The directions also suggested a slate of “Indian Songs” like “From the Land of the Sky-blue Water” and “The Sadness of the Lodge.” Both came from Charles Wakefield Cadman’s Idealized Indian Themes for Pianoforte, said to be derived from Omaha melodies. The final scenes prescribed closure and reconciliation. After being tried by an English court, Anawan died, and mourners attended his “Rude grave” while a piano tinkled “sad music.” A “Short dirge with tom-tom” also sounded. Then an Indian marriage occurred, followed by a symbolic dance set to music signifying “Victory of Peace Over War.” The pageant concluded with a collective rendition of “America the Beautiful.” The sing-along affirmed Euro-American sensibilities about the moral justification of colonial military conquest, and encouraged patriotic sentiments about the U.S. nation-state, a resonant theme in the aftermath of World War I.

Indeed, in contemporary times of global upheaval, King Philip’s War emerged as a way to express anxieties about combat and social roles. William Schofield’s novel Ashes in the Wilderness used music to delineate gender norms as it unabashedly sexualized the sunksquaw Awashonks, whose dance Benjamin Church attended. First serialized as “Narragansett Night,” then published in book form in 1942, the work spoke to concerns of World War II, portraying dashing male heroism and stoicism on fields of battle. Its male protagonists went by jaunty nicknames like Ben and Chris, while Awashonks received the diminutive moniker Fire Girl. A pivotal scene was the Native dance at which Church attempted to win Awashonks’ loyalty to the English. “She danced to the roaring and crackling of the ceremonial flames and the heavy throbbing of the drums—to the thump of naked feet on the hard earth and the rising minor wails of her tribesmen,” read the vaguely pornographic beginning of the dance scene. It devolved into voyeurism as Ben let his masculine colonial gaze rove over the indigenous female body:

Her skin was dripping with sweat, and the firelight glistened over it, making it look like wet bronze. Her slender body weaved and twisted, curving with the dance. He watched her leaping high toward the flame tops, with her back braids tossing wildly and her breast beads outflung; and he watched her stoop earthward, to pound the dirt with clenched fists and then to leap aloft again, her arms thrown upward, her stomach and face gleaming in the firelight.

For an instant, Ben found himself dangerously absorbed with the Native ritual rather than maintaining expected distance as an English spectator: “He caught himself swaying his head from side to side, in time with the rapid pounding of the drums and the yells of the warriors dancing in Fire Girl’s footsteps.” The obvious physical vivacity and sensuality of Awashonks contrasted sharply with the demure roles attributed to Tina, Chris’s colonial love interest.

Perhaps surprisingly, King Philip’s War, unlike other major events and conflicts of early America or the trans-Mississippi frontier, has not received major film treatment à la Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves (1990), Michael Mann’s The Last of the Mohicans (1992), Walt Disney’s Pocahontas (1995), or Mel Gibson’s The Patriot (2000). Those films’ soundtracks, by renowned composers like John Williams and John Barry, achieved widespread acclaim and honors. The closest approximation to popular treatment for King Philip’s War has come not from Hollywood, but from PBS. We Shall Remain, a five-part American Experience series, aired in 2009. The nationally televised production began with an episode titled “After the Mayflower,” which examined Dawnland Algonquian communities like the Wampanoag and their increasingly acrimonious relations with English arrivals. The episode culminated with King Philip’s War, the death of Philip, and the display of his head atop a pike at Plymouth.

Rather than attempting dramatic bombast, the series mounted a sobering investigation that aimed for cultural authenticity and scholarly rigor. Understated music for the entire series was scored by John Kusiak, principal composer for Kusiak Music of Arlington, Massachusetts. Among the credited “Native Music Consultants” were Victoria Lindsay Levine and Annawon Weeden, the former an ethnomusicologist specializing in Amerindian subjects, the latter a Wampanoag actor, performer, and activist who played the role of Philip. The cultural pendulum had begun to swing. Instead of the earnest Euro-American mythologizing (and stereotyping) of the nineteenth century, this production showcased more ethnohistorically grounded types of sound, compatible with the series’ critical perspectives on indigeneity and colonialism.

The most unusual recent treatment of King Philip’s War may be a foray into musical theater. Song on the Windre-animated the forced removal of Natives to Deer Island in Boston Harbor in 1675-76, where many died. Written by David MacAdam, founding pastor of New Life Community Church in Concord, Massachusetts, it was produced through New Life Fine Arts. Song on the Wind interpreted King Philip’s War and its lead-up through a religious lens, focusing on the “Praying Indians.” A multiethnic cast performed scenes of John Eliot’s meeting with potential converts, as well as the beginning of King Philip’s War, sung to the tune “A Shot in the Dark.” For the exile to Deer Island, set designers recreated the windswept island hills inside the theater. That episode portrayed the island internment as a trial of Native converts’ new faith. The first full production premiered in 2004 in an historically resonant location: Littleton, Massachusetts, site of the Praying Town Nashoba. The production received generally enthusiastic receptions. Yet its interpretation of the colonial period was not uncontroversial: “a story of love and betrayal, sacrifice and courage, shared hopes and dreams that transcend racial and cultural differences.” Its emphasis on reconciliation, common humanity, and shared experiences of suffering and grace stands at odds with some Native communities’ (and historians’) emphases on long-term conflict and colonialism, political struggle for decolonization, and a range of perspectives on spirituality and Christianity.

Today in the Northeast, Native music is diverse and dynamic, and often an integral part of commemorations related to King Philip’s War, which remains a sensitive historical touchstone. Native musicians perform at annual commemorations at Deer Island and the massacre grounds at Great Swamp. Besides mourning the wartime loss of ancestors, these are occasions to re-gather communities, speak out against state colonialism, and affirm indigenous and occasionally cross-cultural solidarities for the future. “Drums” and singing groups that perform at community events and on the powwow circuit include tribally specific and intertribal ensembles like the Iron River Singers, Mystic River Singers, Eastern Suns, Nettukkusqk Singers, Wampanoag Nation Singers and Dancers, Urban Thunder, and Rez Dogs. Native-language songs are important components of their repertoires. They audibly demonstrate the revival or recovery of indigenous languages that have been preserved or brought back from endangerment through collective efforts.

Over the past centuries, music keyed to subjects like “Indian War” has performed a range of cultural work. For Euro-Americans, it frequently tapped into serious, deep-seated anxieties about cultural and political legitimacy, and was used to consolidate suitable mythologies about New England’s and America’s foundational moments. Metacom’s Grand March exemplified that spirit. At times, it accomplished a reductive function, making immense violence and dispossession into grounds for public entertainment. Among Algonquian communities, music has conveyed distinctive understandings about a period of tremendous dislocations. It has performed grave, even sacred functions of perpetuating community memory, affirming tribal identities through shared repertoires, and mourning the dead. Perhaps most important, these indigenous musical traditions have pushed back against colonial representations of Indians as defeated, vanished people or romantic stereotypes. Instead, they audibly insist on the endurance and reinvigoration of tribal identities in modernity, in the shared space of the Northeast.

Further reading:

King Philip’s War and its contested meanings have inspired scholarship like Jill Lepore’s The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity (New York, 1998), which analyzed the conflict’s national resonances and effects on language. For an examination of how the war has shaped local understandings of landscape and heritage, see Christine M. DeLucia, “The Memory Frontier: Uncommon Pursuits of Past and Place in the Northeast after King Philip’s War,” The Journal of American History 98:4 (March 2012): 975-997. Sound played a critical role as American settler colonialism and frontier violence pushed across the continent, Sarah Keyes argued in “‘Like a Roaring Lion’: The Overland Trail as a Sonic Conquest,” The Journal of American History 96:1 (June 2009): 19-43.

Roger Williams was an astute though flawed observer of Narragansett culture and language, and he noted the singing “like a Quire” and “lamenting” in A Key into the Language of America: or, An help to the Language of the Natives in that part of America, called New-England. Together with briefe Observations of the Customes, Manners and Worships, &c. of the aforesaid Natives, in Peace and Warre, in Life and Death (London, 1643). Patricia E. Rubertone explored Williams’ legacy and Narragansett mortuary practices, including the brass bells, in Grave Undertakings: An Archaeology of Roger Williams and the Narragansett Indians (Washington, D.C., 2001). Erik R. Seeman critiqued other indigenous and colonial “deathways” inDeath in the New World: Cross-Cultural Encounters, 1492-1800 (Philadelphia, 2010). Mary Rowlandson’s captivity narrative, one of the most widely read and taught texts from early America, is available in a recent edition annotated by Neal Salisbury, The Sovereignty and Goodness of God by Mary Rowlandson with Related Documents (Boston, 1997).

Indigenous, colonial, and European musical/sonic practices all underwent transformations following “contact.” For example, Puritan missionizing sparked Algonquian musical translations among the “Praying Indians,” as Glenda Goodman described in “‘But they differ from us in sound’: Indian Psalmody and the Soundscape of Colonialism, 1651-75,” The William and Mary Quarterly 69: 4 (October 2012): 793-822. Other transformations are traced in Olivia A. Bloechl’sNative American Song at the Frontiers of Early Modern Music (New York, 2008), Gary Tomlinson’s The Singing of the New World: Indigenous Voice in the Era of European Contact (New York, 2007), and Matt Cohen’s The Networked Wilderness: Communicating in Early New England (Minneapolis, 2010).

Euro-American musical representations of Native Americans have been thoroughly examined by Michael Pisani in Imagining Native America in Music (New Haven, 2005). He catalogued relevant sources in “A Chronological Listing of Musical Works on American Indian Subjects, Composed Since 1608” (2006). Thomas Commuck’s biography and collaboration with Thomas Hastings are discussed in Hermine Weigel Williams’ study Thomas Hastings: An Introduction to His Life and Music (Lincoln, Neb., 2005). The influence of Christianity among New England Native communities, along with its intersections with traditional practices and beliefs, continues to capture scholars’ attentions. For surveys about the region’s southern parts, see William S. Simmons and Cheryl L. Simmons, eds., Old Light on Separate Ways: The Narragansett Diary of Joseph Fish, 1765-1776 (Hanover, New Hampshire, 1982), David J. Silverman, Faith and Boundaries: Colonists, Christianity, and Community among the Wampanoag Indians of Martha’s Vineyard, 1600-1871 (New York, 2005), and Linford D. Fisher, The Indian Great Awakening: Religion and the Shaping of Native Cultures in Early America (New York, 2012).

Rufus Choate delivered his plea for mythologizing in “The Importance of Illustrating New-England History By A Series of Romances Like the Waverly Novels,” delivered at Salem, Mass., in 1833, and published in The Works of Rufus Choate, with a Memoir of His Life vol. 1, ed. Samuel Gilman Brown (Boston, 1862): 319-346. This type of mythologizing, which proliferated in nineteenth-century America, tended to distort indigenous histories and deny the contemporary persistence of Algonquian tribal communities, as Jean M. O’Brien argued in Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England (Minneapolis, 2010).

At Mount Hope, Native and non-Native connections to those historically significant grounds have endured through the present day, as Ann McMullen showed in “‘The Heart Interest’: Native Americans at Mount Hope and the King Philip Museum,” in Passionate Hobby: Rudolf Frederick Haffenreffer and the King Philip Museum, ed. Shepard Krech III (Bristol, Rhode Island, 1994): 167-185. Other modern rituals continue to link communities to the 1675 massacre site of Great Swamp; Patricia E. Rubertone has discussed these in “Monuments and Sexual Politics in New England Indian Country,” in The Archaeology of Colonialism: Intimate Encounters and Sexual Effects, eds. Barbara L. Voss and Eleanor Conlin Casella (Cambridge, 2012): 232-251. Contemporary Native music and performance merit an essay of their own. For one Northeastern/Wabanaki case study, see Ann Morrison Spinney’s Passamaquoddy Ceremonial Songs: Aesthetics and Survival (Amherst, Mass., 2010).

Local and regional archives are crucial for uncovering “folk” or vernacular memorial practices. My research on King Philip’s War has taken me to dozens of public libraries, town historical societies and museums, and other small sites, in addition to the perhaps better-known state historical societies of New England and repositories like the American Antiquarian Society. For example, the libraries of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association and Historic Deerfield, located in Deerfield, Mass., contain a wealth of manuscripts, newspaper clippings, and ephemera about commemorations at Bloody Brook, while the Blanding Public Library in Rehoboth, Mass., has materials about “Anawan Rock.” The South County Room of the North Kingstown Free Library in Rhode Island maintains an extensive regional history collection. The Goodnow Library in Sudbury, Mass., holds items pertaining to the Wadsworth monument(s). Collections at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center are useful for Pequot and regional Native studies. I first encountered Metacom’s Grand March not in the Rogers Free Library of Bristol, Rhode Island (home to numerous items about Mount Hope), but in the Special Collections of the Newberry Library in Chicago, which has long supported research on Native topics.

This article originally appeared in issue 13.2 (Winter, 2013).