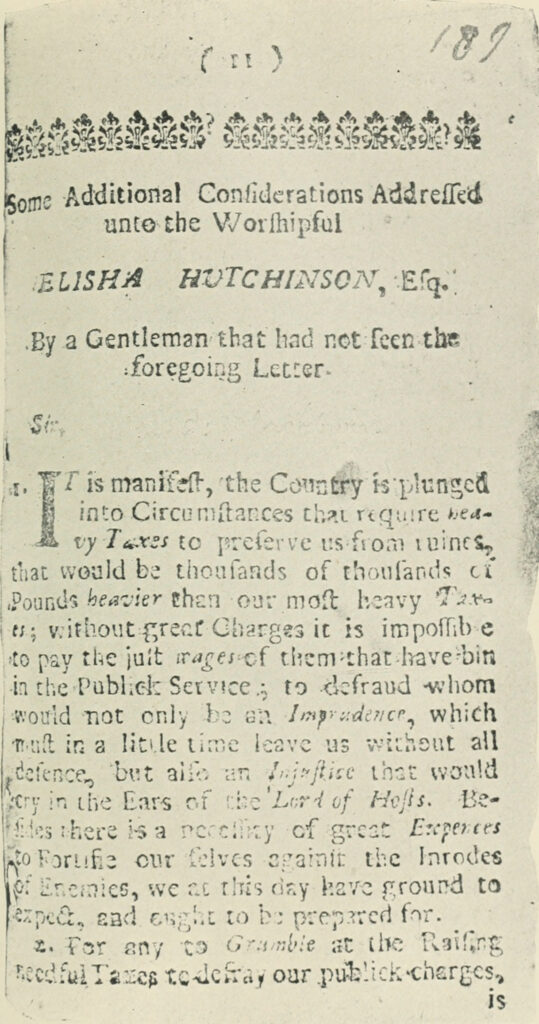

The Hutchinson family is famous in the history of colonial Massachusetts. At the beginning was Anne, a religious dissenter who brought the colony of Massachusetts Bay to the edge of civil war. At the end of the colonial period there was Thomas, a royalist and the last civilian governor. Both were banished by the people of Massachusetts and soon died in exile. Between these failed troublemakers lies Elisha Hutchinson, Anne’s grandson and Thomas’ grandfather. Though far less famous, one of his deeds in Massachusetts influenced the history of the world. This is his story.

The Middle Hutchinson: Elisha, 1641-1717

By leading the risky but eventually successful financial operation, Elisha justified his name.

The Hutchinsons, a family of merchants, left Boston with the banished Anne in 1638. Soon after, Anne’s son Edward returned to Boston. In 1641, his first son was born. The boy was named Elisha after a biblical prophet and miracle worker. The name, meaning “my God’s salvation,” was popular among Puritans and separatists. Young Elisha was never able to hide. First, his grandmother’s legacy was still fresh in memory. Second, he grew to the very unusual height of six feet, two inches (a visiting Londoner would remark he was “the tallest man that I ever beheld”). As the eldest son of a merchant, his career was foretold. He joined his father’s mercantile and real estate business and married a merchant’s daughter named Hannah Hawkins. Through a Rhode Island cousin of the Sanford family, the Hutchinsons sent livestock and food to Barbados. Horses sent to that richest English island operated mills that squeezed sugarcane, extracting the sweet juice and leaving out the slaves’ blood, sweat, and tears. To their credit, Edward and Elisha were brave enough, in spite of Anne’s heretical legacy, to protest Massachusetts’ persecution of Baptists.

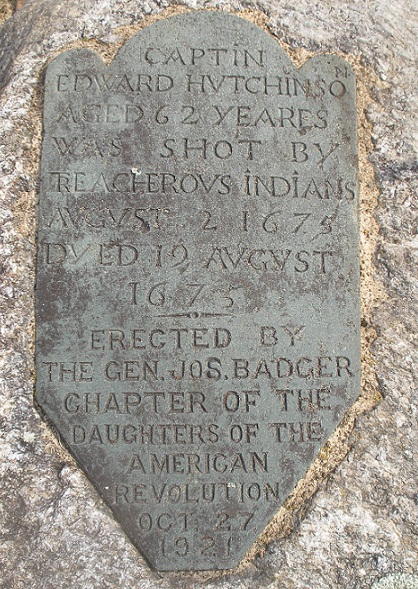

King Philip’s War was a turning point in Elisha’s life. As it began in 1675, Edward Hutchinson was sent on diplomatic missions to secure peace with several tribes. On one such journey the delegation was ambushed and Edward was wounded. He died of his wounds in Marlborough, where his body inaugurated the cemetery. It was probably Elisha, his heir as patriarch of the Hutchinsons, who penned the tombstone’s text: “Captin Edward Hvtchinson aged 62 yeares was shot by treacherovs Indians Avgvst 2 1675 dyed 19 Avgvst 1675.” In line with Puritan tradition, Boston pastor Increase Mather “knew” that Edward died because of a recent church dispute.

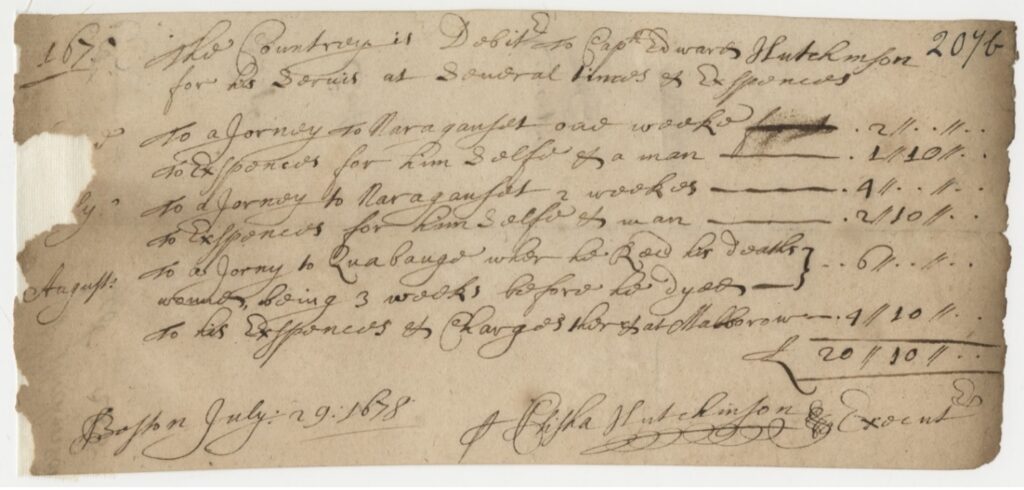

Elisha submitted Edward’s account with the colony in a chilling, formal document: “The country is debitor to Capt. Edward Hutchinson for his service,” including “To a journey to Quabauge where he received his death’s wounds, being 3 weeks before he died.” At the wage of two pounds a week for diplomats, his painful endurance was worth six pounds. Fourteen months later, Elisha lost his wife, Hannah. Like so many other women before the modern age, she died in her seventh childbirth within a decade. This annus horribilis left Elisha alone in charge of both the family and its businesses. As was common, he quickly remarried—a merchant’s daughter again. His new wife, Elizabeth, was recently widowed when her husband, merchant John Freake, was killed in a freak accident: a Virginia ship exploded in Boston harbor.

Boston and the colony soon bombarded the new Hutchinson patriarch with public offices. By 1680 Elisha became a deputy at the legislature (General Court), town councilor, judge in a merchants’ court, sealer of weights and measures, fire officer, and militia captain. The king’s agent Edward Randolph, who led the effort to bring down the chartered government of the Massachusetts Bay Company, identified Elisha as one of the few “great opposers” to the king, and almost had a duel with him. In 1684, Elisha was elected a councilor and continued until a new regime—the Dominion of New England—was imposed in 1686 by England.

Elisha took his offices seriously. The Boston Athenaeum holds a book that belonged to him, a collection of the colony’s laws that he used as a judge and legislator. It is full of notes that he added to make his work accurate and efficient. Bound with the laws is a handwritten copy of Massachusetts’ 1641 Body of Liberties—the only surviving copy of the first English code of laws in America.

During the dictatorial Dominion period, Hutchinson joined a local bank project, but then he left for England to lobby against Governor Edmund Andros’s dismissal of all local land titles. He was soon joined by Harvard president Increase Mather and later by his close friend Samuel Sewall (he appears often in Sewall’s famous diary). In the winter of 1688–1689, Elisha saw the Glorious Revolution in England, but missed a later imitation revolution in Boston, which toppled the Dominion.

Hutchinson and Sewall returned to Boston in December 1689, bringing King William’s tentative approval of the return of General Court rule in Massachusetts. They retook their councilor positions and Hutchinson was appointed militia major as King William’s War worsened. Hutchinson became the leading man on war finance, participating in all the committees that planned the invasions of Acadia and Canada. He wrote about expectations of “plunder enough taken [in Canada] to defray all the charges.” As Boston’s new tax commissioner, he soon reckoned with the failure of these expectations.

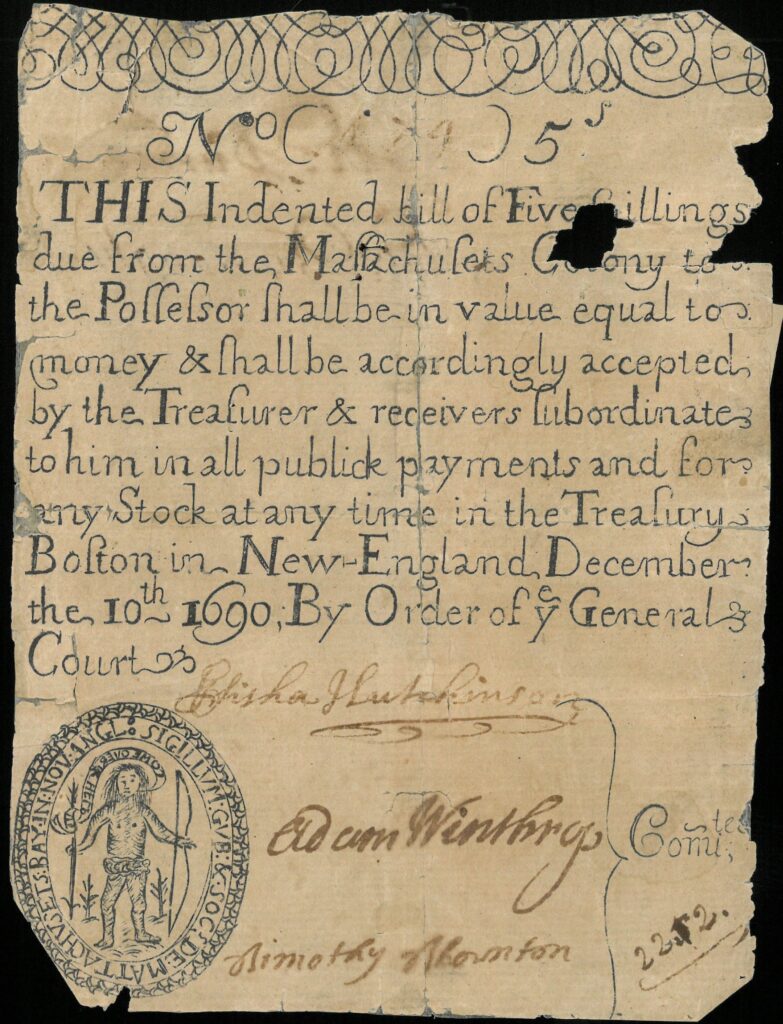

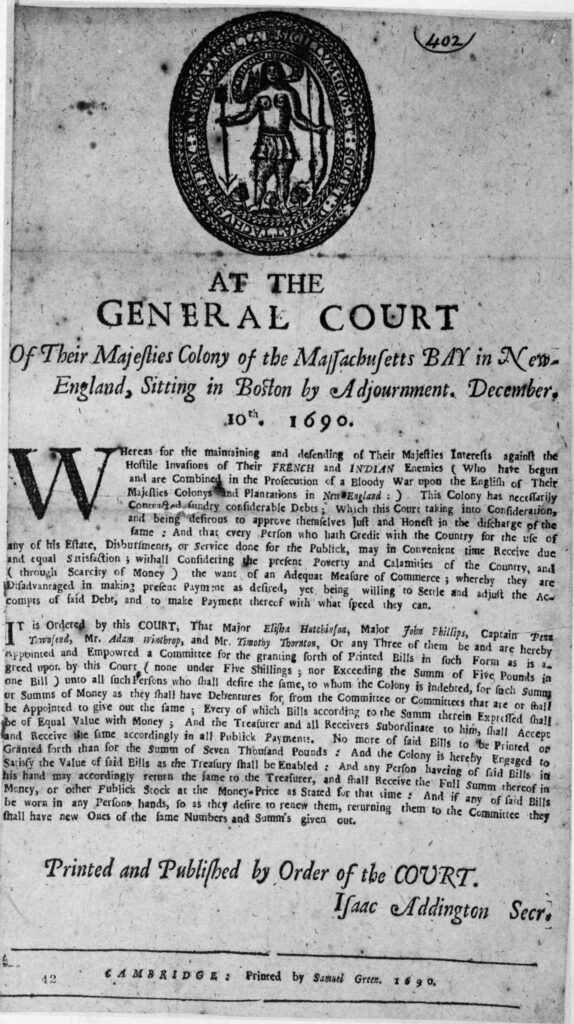

In November 1690, soldiers and sailors returned from Canada defeated and demanding pay, but the government had nothing to give them. Taxes were raised to unprecedented levels to collect funds to pay them, but collecting taxes in a difficult winter, not only in coins but also in grains, would have taken a very long time. The soldiers and sailors became “mutinous,” and so in December 1690 the government resorted to issuing paper money. Those “bills of credit” are commonly known as the first American paper money (which is correct only if “American” refers to the area of the future United States; Dutch Brazil, Antigua, and Canada had already had paper money). But the real significance of the 1690 money was its unique legal status. Unlike all previous paper moneys in (greater) America, Europe, and China, it was not forced on all sellers under threat of penalty and there was no credible promise to convert it into precious metal coins or other valuable commodities. Its only legal support was the government’s commitment to accept it in tax payments (legal tender for taxes in modern terms). This is very similar to our modern currency (which is also legal tender for debts).

The reason for the invention was that England prohibited Massachusetts from creating money. Massachusetts was not among the few colonies whose charter permitted independent coinage. The royal coinage monopoly in England therefore implied that Massachusetts was not allowed to produce coins. However, in 1649 Parliament executed the king and abolished royalty. Therefore, in 1652 Massachusetts opened a mint and made its coins legal tender for debts and taxes. After the Restoration, in the late 1670s, the mint became the key symbolic flashpoint between king and colony and was viewed by English officials as treasonous. Eventually, the mint closed in 1682 and the colony’s charter was revoked in 1684. The issue resurfaced in 1689 as Hutchinson and Sewall helped Increase Mather negotiate with the new monarchs William and Mary about the charter’s renewal.

With such unpleasant recent history, and while still awaiting charter restoration, 1690 Massachusetts could not afford to create formal money, of whatever material. Therefore the colony only made “bills,” which happened to have small, round denominations convenient for shopping, and forced neither soldiers nor sellers to use them as money. Only tax collectors were forced to accept these bills. This was supposed to induce sellers (who were all also taxpayers) to voluntarily accept bills from soldiers.

The government appointed a committee of merchants to issue the bills, granting them much discretion regarding quantity, denominations, and timing. The committee was led by Hutchinson, while Treasurer John Phillips was listed second. In the sixty-year history of hundreds of Massachusetts committees, this was very unusual and thus significant. That the Treasurer was listed second in the colony’s most important financial operation ever, implies that, in modern terms, Elisha sponsored the bill. He either invented the new currency or he supported and promoted it more than others. His experience in trade, war finance, banking, military, tax collection, and diplomacy prepared him to understand that this new money could work: it would be accepted by soldiers, and then by sellers, and England would not mind. Much risk was involved in this unprecedented experiment, but the lives of Anne and Thomas Hutchinson prove that Elisha’s dynasty was fearless to the point of recklessness.

This is not a Great Man story. Hutchinson’s diverse background was representative of his class of legislators. His friend Samuel Sewall, who wrote the draft of the novel paper money, was less experienced as a merchant, diplomat, and militia officer, but he was the owner of the closed mint, a former manager of Boston’s printing press, and a Harvard graduate who might have read relevant monetary ideas by Plato, Aristotle, and Hobbes.

By leading the risky but eventually successful financial operation, Elisha justified his name. He performed a financial miracle and brought salvation to the godly colony. He may have also explicitly prophesized the future of money, but the only recorded prophecy—and an incredibly accurate one—came from pastor Cotton Mather, Increase’s son, who is best known today for the Salem witch trials and early inoculation. Cotton wrote in 1697: “In this extremity they presently found out an expedient, which may serve as an example, for any people in other parts of the world, whose distresses may call for a sudden supply of money to carry them through any important expedition.” As the colony’s founder John Winthrop famously said in 1630 with a different intention, indeed the “eyes of all people” were eventually upon them.

A year and a half later, Elisha was involved in the arrests of elite suspects in the Salem witch trials, and he advised the judges “to see if they could not whip the Devil out of the afflicted.” The colony had recently been rechartered as the Province of the Massachusetts Bay, and Elisha was reelected as a councilor every year. He was never governor or treasurer, but he kept leading paper money committees for the rest of his life.

Grandson Thomas, the renowned historian, wrote that Elisha “seems never to have been successful in business, apt to involve himself in debt upon plans of payment which did not succeed according to expectation.” Thomas specifically noted a later business venture that hurt Elisha so badly he ended up living off his wife’s property. But as the foremost anti-paper money activist in 1740s Massachusetts, Thomas probably also hinted at the events of 1690—Elisha’s reckless plunder forecast that culminated in the beginning of paper money.

When Elisha’s second wife, Elizabeth, died in 1711, she was buried with her first husband, John Freake, surely at her request. Elisha did not give up on her and when he died in 1717, he was buried with them. He continues to fight Freake for her love in the afterlife, forever, under a slab in Boston’s Granary cemetery. He lies just a few feet from the Boston Athenaeum, where his law book is buried.

Elisha Hutchinson, quietly standing in his family tree between a famous grandmother and a famous grandson, was a key figure in a revolutionary moment in the global history of money. He led the first-ever use of money that relied neither on intrinsic value like gold nor on totalitarian forced acceptance in all transactions, but merely on money’s circulation into and out of the treasury of the emerging modern fiscal-military state. In this sense, today we all use Massachusetts money. In spite of its flimsy appearance, this money has been a double-edged sword of immense power, second perhaps only to nuclear weapons: it has performed miracles in wars and recessions but has created nightmarish episodes of inflation worldwide.

Further Reading

The article is based on parts of the author’s book Easy Money: American Puritans and the Invention of Modern Currency, published by the University of Chicago Press in 2023. Specifically, Hutchinson’s first-ever biography (covering his life until the Glorious Revolution) is detailed there in Chapter 11 and is mostly based on records of the City of Boston, Suffolk County, and the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Company, and Samuel Sewall’s diary, as listed in the book’s Notes and References. Chapters 12 and 13 cover the background for the 1690 invention and the invention itself; most of the relevant facts for the episode appear in: Robert E. Moody and Richard C. Simmons, eds. The Glorious Revolution in Massachusetts, Selected Documents, 1689–1692 (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1988). A general account of the Hutchinson dynasty, as written by Governor Thomas Hutchinson, was published in: Peter Orlando Hutchinson, ed. The Diary and Letters of His Excellency Thomas Hutchinson, Esq., vol. 2 (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1886). All these sources are freely available online at the Internet Archive, except for the Colonial Society of Massachusetts volume which is available on the Society’s website.

This article originally appeared in April 2023.

Dror Goldberg is a senior faculty member in the Department of Management and Economics at the Open University of Israel. Before publishing the abovementioned book, his research on the theory, history and law of money was published in academic journals in economics, legal history, and economic history.