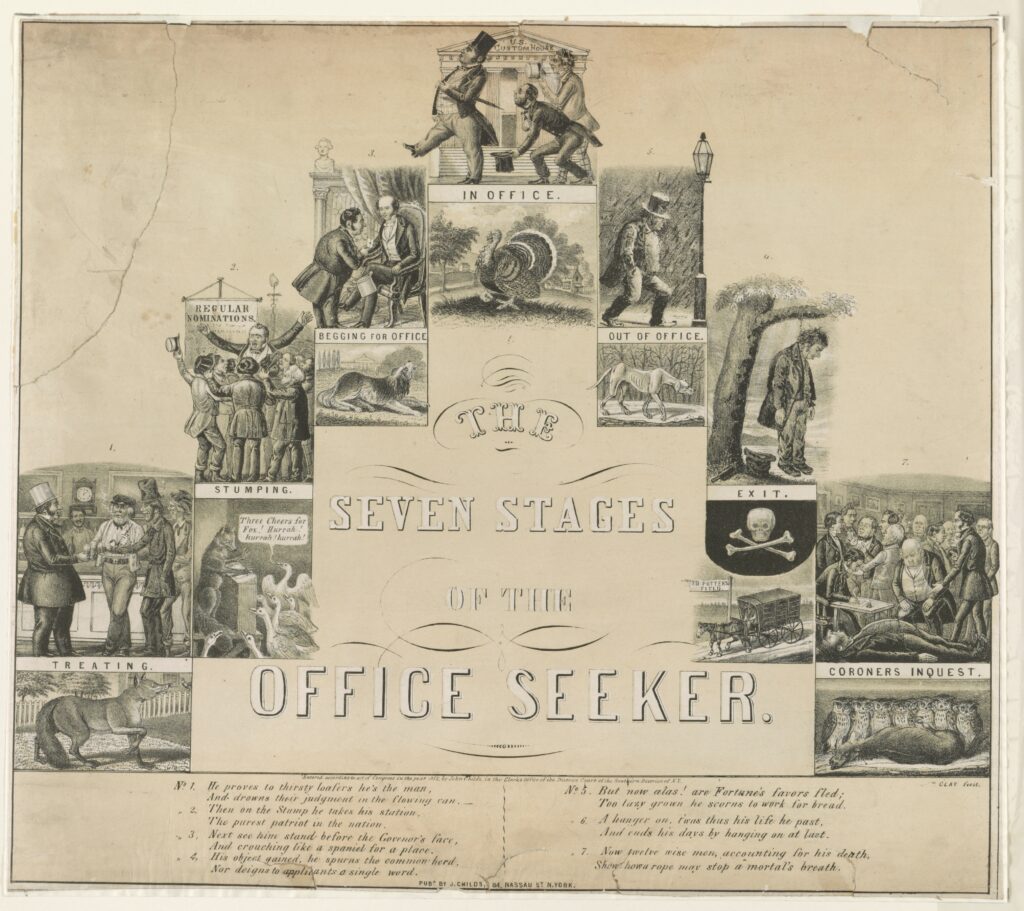

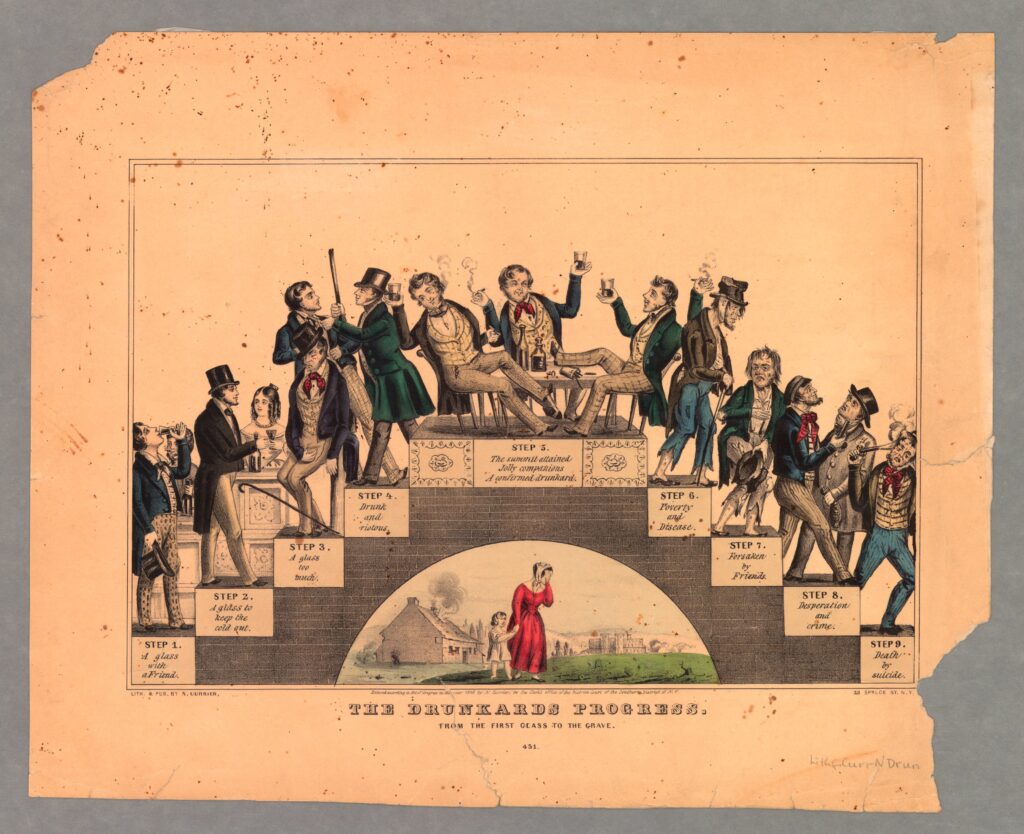

American politics during the 1840s and 1850s was party politics. But the parties themselves were fueled by spoils—the quest for patronage. Edward W. Clay once satirized the spoilsman’s climb to power in “The Seven Stages of the Office Seeker.” The political cartoon follows the rhythms of Nathaniel Currier’s temperance propaganda, “The Drunkard’s Progress.” In Clay’s version, advancing up the party ladder required foxlike skills of servility: plying voters with liquor, food, and flattery; stumping energetically on behalf of a party ticket; and then, like a dog, begging for favor at the feet of party leaders.

The Spoilsman’s Progress

Ambitious office seekers during the nineteenth century experienced wild swings of fortune that depended on the public’s mood and party benevolence.

The summit attained in Clay’s cartoon is glorious, symbolized by the strutting turkey. But removal invariably follows, represented by the avatar of a famished stray dog cast to the streets. A “coroner’s inquest” by the curious public examines the untimely cause of political death. In the final stage, the officeholder’s body is driven to a potter’s field. The spoilsman is discarded and forgotten. Party politics is a system, however, rather than the behavior of an individual, like Currier’s drunkard. The churn of public approbation invariably moves on to the next person. Fittingly, they, too, are destined to be a victim of party abuse.

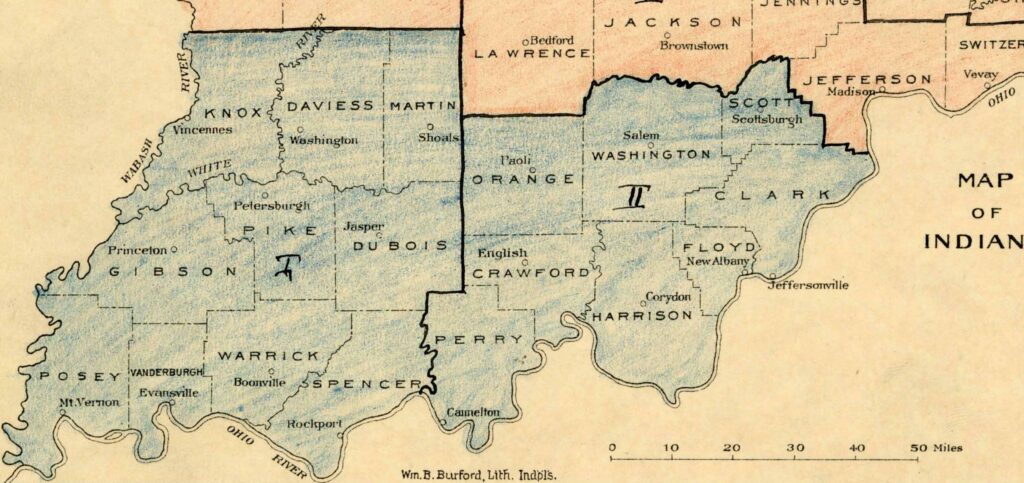

While some antebellum politicians did enjoy lengthy careers, two diplomats from Indiana’s First Congressional District, George H. Proffit and Robert Dale Owen, fit Edward Clay’s satirical arc remarkably well. Southwestern Indiana was an unlikely wellspring of diplomatic talent. The district spanned a region of the state called the Pocket. A narrow strip of counties located snugly between the Wabash and Ohio Rivers, the name took hold after the U.S. Congress carved Illinois out of Indiana Territory.

George H. Proffit served in the U.S. House from this seat from 1839 to 1843. A Whig merchant posted to Brazil by President John Tyler between December 1843 and August 1844, his sojourn was cut short by feuds stemming from presidential succession and party dissensus. Robert Dale Owen, an agrarian Democrat, succeeded Proffit in office for two terms in the U.S. House, after which he was sent to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1855 by Franklin Pierce. By the time Owen returned home in 1858, he found himself an outcast within his own party as a unionist with antislavery inclinations trapped within the party of secession.

Diplomatic Spoils

Diplomatic posts were highly coveted political rewards during the antebellum period. Foreign affairs were one of the few powers exercised robustly by the federal government, along with military functions, the regulation of commerce, and delivering the mail. Unlike a postmastership or a job at the customhouse (the latter is noted at the peak of Clay’s cartoon), diplomatic appointments came with the allure of prestige. Serving your country on foreign soil was still the domain of nobility among the world’s great powers. In the early American republic, the arena remained an honor reserved for the elite,

By the 1840s, however, a mission abroad dangled the prospect of status to even the most mediocre of placemen. Appointments also held out the prospect, if rarely the fact, of traveling in style to seemingly exotic places. Literary figures—writers, artists, and educators—sought foreign postings as way to travel widely while drawing upon a government salary.

The pathways of these two rivals, Proffit and Owen, to diplomatic appointments, and the ordeals they faced, tell us an important story about the old spoils system. Ambitious office seekers during the nineteenth century experienced wild swings of fortune that depended on the public’s mood and party benevolence. Hard work and good connections might carry political loyalists on a wave from obscurity to relative grandeur. But the threat of removal, dispossession, and even ostracism was always lurking around the corner.

For-Proffit Government

During the 1830s and 1840s, George H. Proffit served constituents simultaneously as a Whig official, federal bureaucrat, and as local merchant. The lengthy and contested process of Native dispossession was still underway when both he and Robert Dale Owen made their careers in southwestern Indiana. President Andrew Jackson’s policy of accelerating forced removal was overseen in the field by Proffit, an Indian Agent for the War Department, along with several other leading Indiana politicians.

Native peoples openly despised Proffit. On one occasion he was almost knifed in plain day in the Summer of 1837 at an encampment near Lake Keewaunay. An English-speaking Potawatomi woman, Do-Ga, christened him “Ko-cheese,” or louse, for the lack of respect he showed the families preparing for a long journey westward that would become a trail of death.

“Ko-cheese” was stuck to the beating heart of the Mississippi watershed’s borderland political economy. Born in New Orleans, Proffit began his career in the 1820s as a bargeman transporting goods along the Ohio River. At the time he represented Pike and Dubois Counties in the Indiana House of Representatives, championing a Mammoth System of canals and highways, he was also administering the federal government’s expulsion of the Potawatomi from Crooked Creek, earning a salary of $4 per day.

Proffit’s role in Native expulsion opened a path for the region’s land sales; and he purchased aggressively, buying roughly 1,500 acres of land around Petersburg and several lots in town. The Whig-backed system of state canals and highways that he promoted in the late 1830s aimed to valorize those new landholdings, including two of his lots in Evansville, the southernmost terminus of the Wabash and Erie Canal. Profitt was foremost a businessman. Treaty annuities paid by the federal government to Native peoples as legal compensation for lost territory were spent buying supplies from his two country stores.

Owenism After Utopia

Unlike his Whig opponent, Robert Dale Owen had no interest or capacity for business. He was known primarily by his connection to New Harmony, the utopian community founded by his father of roughly 800 people who moved onto 20,000 acres. Located off the banks of the Wabash River in Posey County, Indiana, the commune was launched in 1826 when it was a village of “four streets running toward the river, & six crossing these.” Robert the elder, an “enthusiastic talker” who carried himself with the countenance of a Roman senator, made a fortune in the textile mills of New Lanark, Scotland. But he decried the cut-throat competition and child labor produced by early industrial capitalism.

On the edge of American empire, the industrialist put visionary ideas about cooperative property to the test. He called it the “Social System.” But the experiment struggled almost immediately. The legacy of New Harmony lived on as the material basis for the son Robert Dale’s life as a bohemian radical. The patriarch conveyed the remaining property, an enormous estate worth $140,000 at its peak, to his family who stayed behind in America.

Robert Dale Owen established the Free Enquirer along with Fanny Wright. They expounded upon everything from Black emancipation to universal education to birth control when most Americans considered the topics risible. Living for a time in New York City, he supported the fledgling Working Men’s Party. So, the dedicated but small free-thinking community across the United States was surprised, and more than a bit disappointed, when he returned home to the Pocket and evolved into a committed Democratic partisan.

What first pulled into party politics was precisely that very thing upon which all republics are founded—the demand for more say in how his property was governed. He sprang into action in 1835 when he learned that his enormous New Harmony estate would be bypassed by the construction of the Wabash and Erie Canal, championed by George H. Proffit and the Whigs. After lobbying efforts to bring the canal route to his hometown faltered, Owen won election to the Indiana General Assembly and minor victories for the “modifiers” covering the pacing of construction and the payment of public debts.

In his new path, Robert Dale Owen proved to be an adept legislator with a reputation for compromise. “Practicable reforms” like channeling federal money to Indiana’s fledgling common schools or reforming state law so that widows could inherit property were “not radical as you understand the term,” he confessed to his father. But the measures were of “unquestionable utility as far as they go.” During his tenure in the U.S. House of Representatives, Owen was instrumental to building a coalition that finally chartered the Smithsonian Institution after eight years of inaction.

By 1845, the Indiana State Sentinel could proclaim in earnest that Owen “is the last man now living in the State” who would “violate his allegiance to just party discipline in the slightest degree whatever.” Defending President James Polk’s annexation plan in a speech on the House floor, Owen allowed to critics that it was unfortunate Texas was a slave republic. “But shall we count it for nothing, on the other hand,” he reasoned, “that we increase also, by one-sixth, our Union; happy, prosperous, blessed, even with her faults, as we feel her to be”? To this, he added: “We can find no Utopia to annex.”

Stumping

George H. Proffit was a “high toned but humorous whig.” Yet, he proved to be inept as legislator. In early 1842, Proffit and five other pro-slavery members of the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs quit in protest after John Quincy Adams’s reading of anti-slavery petitions. The sixth president deftly outmaneuvered them. Chairman Adams accepted their resignations and voted to replace them by a “shout of acclamation” from the remaining committee members. The rest of Proffit’s record in Congress was hardly more distinguished. He was a stump speaker, not a legislator.

As Edward Clay’s cartoon about the spoils system illustrates, campaigning was the kind of party service that mattered. The power to hold an audience’s attention was decisive in this era of mass politics. Entire careers, like those of Daniel Webster or Henry Clay, were built upon delivering orations, rhetorical expressions of moral superiority that were laden with references in Latin and Greek. Nobody could mistake George Proffit for such a gentleman. He was crude, funny, and relatable—a western politician.

When Proffit took the stump, he came “loaded seven fingers,” like a muzzle gun so heavily charged that the ramrod stood out seven inches. His specialty was the rousing “spread eagle” speech, a blend of patriotic sentimentality and partisan invective. He charged that Democrats were all Locofocos who would be content without nothing less than the destruction of banks, “robbing children of the property of their fathers,” overturning the schoolmasters’ authority, and, more generally, for sending humanity back to the Iron Age. Western politics was a form of entertainment, after all, and Proffit knew how to put on a good show. “I have never heard a more persuasive speaker,” one traveler noted in his diary.

During the campaign of 1840, George H. Proffit and Robert Dale Owen faced off against each other to represent the First District in the U.S. House of Representatives. They traveled together across the Pocket’s backroads, as was the custom, for two long, hot months in the summer of 1839, riding together on horseback to speak before crowds at towns, county seats, and at impromptu roadside encounters. They would speak for hours at a time, notwithstanding interruptions from the crowd, followed by lengthy rebuttals.

Proffit’s manner of speaking was honed at the country store. There, intimacy and mutual trust were the coin of the realm. Owen was at a disadvantage on the stump. He relied on a plodding style of argumentation—lecturing, really—developed during his years as a gadfly denouncing the ills of society to thin crowds at the Hall of Science in New York City, an assembly for radicals.

Owen was earnest on the campaign trail, not entertaining. He had the awkward habit “of keeping his hands in his breeches pockets,” a Whig paper observed. “As he warms and rises in the importance of his subject, deeper does he plunge his hands into his breeches.” By most accounts, Owen did himself few favors when delivering a stump speech. He lost to Proffit by a 13 percent margin, a rout that cannot be fully attributed to late entrance into the race.

Rather than fold after this harrowing defeat, Robert Dale Owen returned to the campaign trail time and again. He became a regular party speaker, aided in part by sheer availability. That is, he could afford to spend months away from business affairs focused on the election canvass, doing committee work, and attending conventions.

Owen traveled the electioneering circuit for Martin Van Buren in 1840, James Polk in 1844 and Lewis Cass in 1848, not to mention for his own U.S. House campaigns. Owen eventually learned to give a passable speech through workman-like practice and sheer force of will. He proved indefatigable, an advantage in party service during this era that was second only to skills at speechifying.

In and Out of Office

When George H. Proffit embarked in the Summer of 1843 for Rio de Janeiro on the USS Levant, a sloop-of-war that shuttled diplomats to their posts in Latin America, his appointment was the culmination of a long career in public life. Proffit was a popular congressman, and, before that, a state legislator. Now he was leaving the backwoods of southern Indiana, with its coarse manners and meagre living, to serve as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the court of Brazilian Emperor Pedro II. A group of New York merchants even organized a dinner celebrating the Hoosier’s departure for “standing manfully in defence [sic] of the President.”

The journey was not easy. It took two and a half months amid squelching heat to make the voyage from Hampton Roads on the Virginia coast to Rio, crossing the Caribbean and making port several times on the way. And then, after all these labors, Proffit’s tour of duty was over almost as soon as it began. He arrived in Brazil with an unfortunate status as a diplomat without the confidence of his own government.

Mere weeks after disembarking, the U.S. Senate rejected George Proffitt’s confirmation as minister by a vote of thirty-three to eight. More than a disappointment, it was a humiliation. In 1842, John Tyler—an accidental president after the death of William Henry Harrison—had broken decisively with the Whigs after vetoing party-line measures on banking and the tariff. After waiting more than a decade in the opposition, Whigs lost a chance—their only, it would turn out—to govern as a majority on the party’s own terms. Congressman Proffit followed Tyler into political apostasy and received his just reward, a recess appointment for the Brazilian mission at $9,000 per year (or about $300,000 today).

The personal triumph was brief. Henry Clay, the Whig leader preparing to run for president, bitterly denounced Proffit on the Senate floor, along with other members of Tyler’s “corporal’s guard” of ex-Whigs seeking patronage. Following humiliation came disaster. On February 28, the twelve-inch guns of the USS Princeton exploded during official inspection. The accident brought a sudden and gruesome end to Tyler’s Secretary of State, Abel P. Upshur, who envisioned uniting pro-slavery forces in the Western hemisphere by forming a grand alliance with Brazil. The State Department was rudderless at the very moment that Proffit had been stripped of authority by the U.S. Senate. Essentially, he was stranded in South America.

A mere eight months after leaving home, then, acting-Minister Proffit slunk quietly back into the country on the USS Cyane. Earlier, during the heady moment of Whig triumph in the Election of 1840, he had been celebrated as a party hero. His frenzied efforts stumping on behalf of the Harrison-Tyler ticket were decisive in carrying Indiana’s Democratic-leaning Pike County by a razor-thin margin of 156 votes. “We have a whole team in the person of little George H. Proffit,” boasted a local party paper, marveling at the energy of a man who was but 5 feet and 4 ½ inches tall.

Upon returning from Brazil, Proffit was abandoned by longtime friends who believed that he dropped the Whig standard for little more than a patronage grab. He was hounded by local papers as “the little traitor.” Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, a longstanding antagonist, crowed that Proffit’s diplomatic tenure was so irrelevant that he was never formally received at court. In truth, the alleged slight was likely due to poor timing: the newly coronated Emperor’s feud with his brother-in-law, the Count of Aquila, had brought court affairs to a standstill. The palace of São Cristóvão also happened to be under renovation. Still, the charge appeared to confirm Proffit’s sudden irrelevance.

But there was yet lower to fall. The rigors of midcentury long-distance travel and the weight of ostracism taxed Proffit’s physical stamina and mental health to a breaking point. He was dead within two years. The lesson weighed heavily on Robert Dale Owen, the Democratic rival who Proffit handily defeated in 1840, but who later succeeded him in Congress. When the possibility of Owen’s own foreign mission arose, he was initially cautious. He did not wish to “bury himself in South America.” What initially looked like a lucrative emolument and rare honor for his Whig predecessor turned out to be a cautionary tale.

Coroner’s Inquest

In the battle to serve as Franklin Pierce’s chargé d’affaires to Naples, Robert Dale Owen, the social reformer, was chosen over August Belmont, the financier with business in Italy. Like Profitt’s post to Brazil, Owen was appointed as reward for political service. He had supported the 1852 presidential aspirations of Joseph Lane, a former state legislator representing Evansville, a city on the Ohio River within Owen’s U.S. House district. During the Mexican-American War, he helped Lane to secure the rank of brigadier general.

After the war, General Lane’s career took off as territorial governor of Oregon and later its U.S. Senator. Declaring Lane “the Andrew Jackson of Indiana,” Owen promoted him in party correspondence, spoke at meetings on Lane’s behalf, and shepherded resolutions of endorsement as the first choice of Indiana Democrats. Owen also penned an official campaign biography under the pseudonym “Western.” It was then Lane who recommended Owen to President Pierce; it was Lane’s influence that prevailed over August Belmont. Congressman Owen, the erstwhile patron, had himself become supplicant, per Edward Clay’s cartoon, “begging for office.”

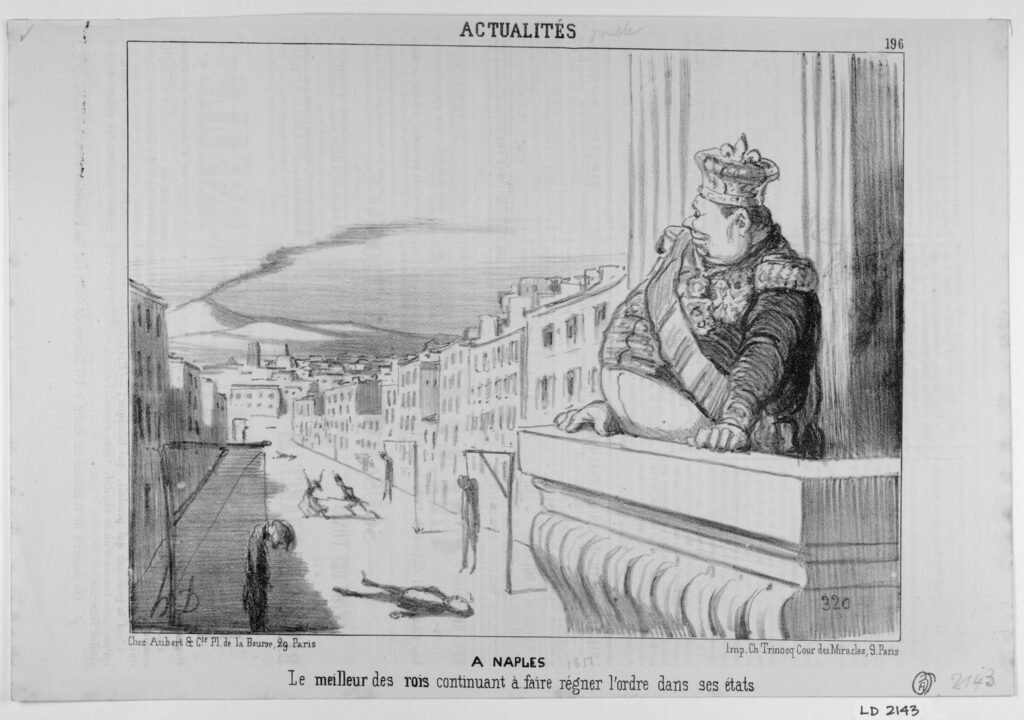

When Owen arrived at his post in late October 1853, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies hung on the precipice of collapse. Ferdinand II, a plump and epileptic despot, governed tenuously. His polity had been restored out of the ashes of foreign invasion. Memories of Napoleonic rule and Austrian occupation were still fresh. The throne was besieged by conspiracies at home and threatened by a regional conflict that erupted into the Crimean War. The scourge of liberals everywhere, Ferdinand had earned the nickname “Bomba” for quashing the barricades of 1848. He reigned through a heavy hand of police and censorship.

And yet, Owen, that oracle of humanity’s progress in his youth, the radical egalitarian, embraced the perquisites of life in this minor Bourbon court. He rented lodgings at Palazzo Valli in Chiaia, on the waterfront, with a breathtaking view of the bay from his window. It was a fashionable neighborhood of palatial homes where carriage traffic was three or four abreast in busy late afternoons. Owen kept servants, as was the custom of rank in which he conducted affairs. He attended balls at the royal academy. And he won the king’s personal favor by refusing to cloak the day’s great power politics in the shroud of humanitarian rhetoric, as did England.

Robert Dale Owen proved to be a high-functioning bureaucrat, remaining at his post even during a cholera outbreak in June of 1854. He was promoted to minister resident after a year in office. When Owen’s four-year tenure was nearing an end, he confided to Secretary of State Lewis Cass that he could not bear to leave “one of the most beautiful regions” of the world “without regret.” Owen lobbied James Buchanan, asking to be kept in his post, even for just another year.

Would the president consider Owen’s record of accomplishment? Despite no prior diplomatic experience, he had negotiated a trade agreement, served American nationals well (both seamen and travelers), and, more generally, cemented amiable ties between the two nations. Buchanan, however, was a consummate Jacksonian committed to rotation in office. The president-elect did not even entertain the possibility. It was simply time for another party man to enjoy the emoluments of office.

On September 20, 1858, Owen was formally recalled. He boarded a steamer headed for Marseille and, eventually, back home. Unlike Proffit’s defrocking, Robert Dale Owen went on to live another thirty years, with many adventures still to come. But as predicted by Edward Clay’s “The Seven Stages of the Office Seeker,” Owen’s political career was buried in a potter’s field just the same. He never held public office again.

Further Reading:

Primary Sources

Adams, John Quincy. Diary Entry, January 31 and February 9, 1842, Volume 34. John Quincy Adams Digital Diary. Massachusetts Historical Society.

Owen, Robert Dale to Robert Owen. September 3, 1854, Folder 5, Box 1. Robert Dale Owen Papers. Indiana State Library.

Proffit, George H. Loco-focoism As Displayed in the Boston Magazine, Against Schools and Ministers, and in Favor of Robbing Children of the Property of their Parents! Christians! Patriots! Fathers! Read and Reflect! 1840. HathiTrust, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hx26wf&seq=5.

Texas and her Relations with Mexico. Speech by Robert Dale Owen of Indiana, delivered in the House of Representatives of the United States, January 8, 1845. Library of Congress Digital Collections, https://lccn.loc.gov/42035488.

Secondary Sources

Acton, Harold. The Last Bourbons of Naples, 1825-1861. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1961.

Barman, Roderick J. Citizen Emperor: Pedro II and the Making of Brazil, 1825-1891. Stanford University Press, 1999.

Carmony, Donald F. and Josephine M. Elliot, “New Harmony: Robert Owen’s Seedbed For Utopia” Indiana Magazine of History LXXVI (September 1980): 161-261.

Etcheson, Nicole. The Emerging Midwest: Upland Southerners and the Political Culture of the Old Northwest, 1787-1861. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1996.

Leopold, Richard. Robert Dale Owen: A Biography. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1940.

Sears, Louis M. “Robert Dale Owen’s Mission To Naples.” Indiana Historical Bulletin VI Extra No. 2 (May 1929): 43-51.

Wilson, George R. “George H. Proffit: His Day and Generation.” Indiana Magazine of History Vol. 18, No. 1 (1922): 1-46.

This article originally appeared in June 2025.

Jeffrey D. Broxmeyer is associate professor in the Department of Political Science and Public Administration at The University of Toledo. His first book, Electoral Capitalism: The Party System In New York’s Gilded Age, was published in 2020 by University of Pennsylvania Press. He is currently at work on a second book project that reexamines the spoils system across the nineteenth century in American politics.