When British troops invaded the city of Washington on August 24, 1814, their orders were to capture the city, and “complete the destruction of the public buildings with the least possible delay.” In perhaps the most memorable event of the War of 1812, they set ablaze the interior of the United States Capitol, the president’s house, and the public offices, in retaliation for the looting and burning of the capital city of York in Upper Canada (present-day Toronto) by American troops the previous year.

At the Capitol building, the British forces used the books from the 3,000-volume congressional library to kindle the fire that reduced the north wing to charred timbers (fig. 1). Lovers of literature and learning, even the British press, denounced the destruction of the library. The editor of a Nottingham newspaper called it “an act without example in modern wars or in any other war since the inroads of the barbarians who conflagrated Rome and overthrew the Roman Empire.” British Major-General Robert Ross, who ordered the burning of public buildings, was reported to have said, “Had I known in time, the books most certainly should have been saved.”

Retired president Thomas Jefferson got wind of the burning of Washington from Monticello, his residence in the Virginia Piedmont, sometime around August 28, 1814, most likely via reports published in the Richmond Enquirer newspaper. Four weeks later, the deeply indebted Jefferson offered to sell his library to Congress to replace the one that was destroyed. What was the motivation behind this move? Jefferson biographers and historians have typically portrayed his offer and later the sale as purely opportunistic, and have characterized his motive in primarily financial terms. Even Jefferson descendant Sarah N. Randolph asserted in her 1871 biography, The Domestic Life of Thomas Jefferson, that it was her great-grandfather’s financial situation that led to the sale of his library. Writing about Jefferson’s pecuniary pressures, which grew more urgent with the war, she stated, “There was then nothing to be made from farming; but while his income was thus cut short, his company and his debts continued to increase. In this emergency something had to be done; and the only thing which offered itself involved a sacrifice which none but his own family, who witnessed the struggle it cost him, could ever fully appreciate.”

While Jefferson certainly benefited from and used the proceeds from the sale of his library to settle some of his debts, might his motives have been more multifaceted than previously understood? This article examines this question against the backdrop of the partisan politics surrounding the 1815 sale, while shedding light on the lesser-known and elaborate preparations Jefferson undertook to ensure that his prized collection would be installed in the nation’s capital “very perfectly in the order” he had envisaged.

On September 15, a week before Jefferson offered his library for sale, he received a letter sent from Philadelphia by Boston publisher Thomas B. Wait & Sons. They were in the midst of publishing a collection of State Papers and Publick Documents of the United States, for the use of Congress and the general public, to fill a need they perceived had been amplified by the war with Great Britain and tangled relations with other European powers. Their efforts were now in jeopardy because of the destruction of the documents they needed for the publication that had been housed in the congressional library in Washington. They turned to Jefferson as a last resort and wrote, “In our dilemma, the idea occurred, that you sir, would more probably have in your possession a complete series of Amer. State Papers, than any man in the country; and the remarks of many of our friends strengthened us in the hope that the desired papers might be found in your hands.” This request likely served to underline for Jefferson Congress’s dire need for a reference library in order to function effectively. Might this realization have played a part in, and even been the impetus for, Jefferson’s move a week later to offer his personal library to the nation? Jefferson had a close personal connection to the congressional library. During his tenure as president of the United States from 1801 to 1809, Jefferson had maintained a keen interest in the library and its development. Most notably, in 1802, he drew up a list of recommended books for Congress, which helped shape the library’s acquisitions at least until 1806. He was keenly aware of the resources the legislative body needed. Congress was now without a library, and Jefferson was uniquely positioned to fill this need.

On September 21, 1814, Thomas Jefferson wrote to his longtime friend in Washington and federal commissioner of the revenue, Samuel Harrison Smith. He expressed his indignation at the “vandalism of our enemy,” declaring the British acts of aggression and barbarism as tyranny of the strong over the weak and unbecoming of a European power in a civilized age. He then offered to sell his personal library to Congress as a replacement. “I have been 50. years making it, & have spared no pains, opportunity or expence to make it what it is,” wrote Jefferson of his collection that had “no subject to which a member of Congress may not have occasion to refer.”

Jefferson offered to sell his library at whatever valuation and payment terms Congress should decide upon, on the condition that it be purchased in its entirety or not at all. Jefferson believed that no other collection of its kind existed in terms of its comprehensiveness and depth, which made it ideal to meet the immediate reference needs of the members of Congress. He wrote, “While residing in Paris I devoted every afternoon I was disengaged, for a summer or two, in examining all the principal bookstores, turning over every book with my own hands, and putting by every thing which related to America, and indeed whatever was rare & valuable in every science. besides this, I had standing orders, during the whole time I was in Europe, in it’s principal book-marts, particularly Amsterdam, Frankfort, Madrid and London, for such works relating to America as could be found in Paris. so that, in that department, particularly, such a collection was made as probably can never again be effected; because it is hardly probable that the same opportunities, the same time, industry, perseverance, and expence, with some knolege of the bibliography of the subject will again happen to be in concurrence.” He continued, “after my return to America, I was led to procure also whatever related to the duties of those in the high concerns of the nation … in the diplomatic and Parliamentary branches, it is particularly full.”

Having detailed the efforts he took to acquire such a useful collection for matters of state, Jefferson noted that he had long been thinking of Congress as the site of its ultimate disposition. “It is long since I have been sensible it ought not to continue private property, and had provided that, at my death, Congress should have the refusal of it, at their own price.” Now with Congress’s devastating loss, he felt that the present was the proper time to offer to place the library at their service, even if that meant the seventy-one-year-old Jefferson would give up its use for the remainder of his life.

In separate correspondence describing this offer to President James Madison and also Secretary of State and later Secretary of War, James Monroe, Jefferson reiterated his willingness to accept any valuation determined by persons appointed by Congress and any other terms decided by them. On the subject of purchase price, Jefferson balked at assigning a value to his library, on the grounds that he was not sufficiently familiar with current prices, and that he was not willing to trust himself in a case where “motives of interest” might subject him to bias, or the suspicion of it. His hope was that Congress would appoint an agent, someone knowledgeable like a bookseller, to arrive at an independent volume count and a maximum ceiling price for the entire collection. Congress could then decide to approve or reduce the proposed price. He wrote, “In all this I wish myself to be entirely passive, and to abide absolutely by the estimate thus formed.” To Monroe, he stated his readiness to accept payment even after the war, “at such epoch as they may chuse after the days of peace & prosperity shall have returned.”

If Jefferson’s chief goal in offering his library to Congress was to raise funds to help pay his personal debts and alleviate his financial woes, two questions arise. How would attempting to sell his library to a wartime government under financial duress and intense public scrutiny, at a price it alone set, achieve this end? The Madison administration faced a banking crisis, widespread economic uncertainty and enormous pressure to raise taxes. Furthermore, if Jefferson was selling his prized collection expressly to pay off pressing debts, how would accepting payment at some indeterminate date in the future, also of Congress’s own choosing, accomplish this goal? If debt relief was indeed Jefferson’s primary motive, one might have expected him to try, at least subtly, to maximize his proceeds from the sale. Yet, there is a glaring absence in surviving correspondence of any attempt by Jefferson to allude to a preferred purchase price or valuation. Nor did he place any emphasis on the most valuable and rare items in the collection. For example, an edition of Richard Hakluyt’s The Principall Navigations, Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation was selling for the equivalent of nearly $140 on the London book market, fourteen times more than the $10 Jefferson eventually received for his 1589 folio edition. Similarly, Mark Catesby’s The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands was selling for more than $115, over five times the $20 he received for his two-volume folio set published in 1771. Instead, he encouraged Smith to come up with a figure he himself deemed reasonable for the entire collection, and suggested that he do so by applying an average price for each volume based upon size. “Whatever sum you should name shall be binding on me as a maximum,” he wrote Smith.

© Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello.

Jefferson’s emphasis on Congress’s acquiring his library in its entirety or not at all suggests the operation of a motive even more important than financial gain: Jefferson saw his carefully curated assemblage of literary treasures, many irreplaceable, as a reflection of who he was, the values he believed in, and how he wanted to be regarded by his fellow countrymen and by posterity—as the champion of a nation of enlightened and free men (fig. 2). The library was to be kept intact. He would not suffer it to be broken up or sold piecemeal. Parting with the collection he had painstakingly assembled over five decades was no small decision for Jefferson. Sarah N. Randolph described his library as “the books which in every change in the tide of his eventful life had ever remained to him as old friends with unchanged faces, and whose silent companionship had afforded him—next to the love of his friends—the sweetest and purest joys of life.” Yet parting with the library at this time was warranted because Jefferson strongly felt that in order for Congress to govern effectively, it needed access to a working library of books and documents relating to all aspects of human knowledge.

It would, of course, overstate the case to say that Jefferson’s sale of his library to Congress was a completely altruistic gesture. He could, one might argue, simply have donated the library to Congress, which we have no evidence that he considered doing. The reality was that Jefferson was deeply in debt and had built up his library at considerable personal expense. Even if he had wanted to, he could not at this time have afforded to give the library away. There is evidence that years earlier, Jefferson had considered donating his scientific books through his will to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, of which he was president. That consideration was now subsumed in the greater mission of leaving his library intact as a personal and republican legacy of greater usefulness to Congress while addressing pressing financial exigencies.

Jefferson may also have come to believe that selling the library to Congress at a fair price was a demonstration of the superiority of private property rights over collective ownership, a core idea of the Scottish Enlightenment and influential thinkers such as David Hume and Adam Smith, promoted by George Washington, Madison, and Jefferson himself. “The true foundation of republican government is the equal right of every citizen in his person, & property, & in their management,” Jefferson wrote. By offering to sell, rather than donate, his library, he was acting in accordance with his republican ideals, and exercising his ownership rights by having Congress provide adequate compensation to him for ceding his library to it.

The politics of purchasing the ex-president’s books

Samuel Harrison Smith, who had expressed optimism early on about Congress’s approval of the library acquisition, underestimated partisan reactions to the offer. He forwarded Jefferson’s offer on October 3 to Senator Robert H. Goldsborough, the chairman of the congressional Joint Library Committee, who introduced a resolution four days later authorizing the committee to enter into negotiations with Jefferson for the purchase of his library. The resolution passed in the Democratic-Republican-dominated Senate without any debate on October 10. However, on October 19 the House of Representatives followed suit adding an amendment that Congress retain the right to accept or reject the final contract. This came after failed attempts by opponents of the proposal to exclude certain books and to impose a price ceiling. Voting in the House, which was two-thirds Democratic-Republican, was largely along partisan lines.

The Library Committee met with Smith on October 21, and decided that they would submit for congressional approval whatever valuation Smith proposed to be a fair sum. Smith sought Jefferson’s input, but the latter refused to stipulate a price, reiterating his desire that Congress appoint an independent party to arrive at a valuation. To assist Smith, Jefferson requested his Georgetown bookseller and bookbinder, Joseph Milligan, who was familiar with Jefferson’s library and its condition, to obtain a count of the volumes on each page of the library catalogue Jefferson kept, arrive at an average price for each volume, and report them to Smith. Milligan was a trusted associate of Jefferson’s, and an individual known to Smith. The final count presented to the Library Committee was 6,487 volumes valued at $23,950, based on Milligan’s formula of $10 for a folio, $6 for a quarto, $3 for an octavo, and $1 per duodecimo. Jefferson did not contest or attempt to raise the prices fixed by Milligan. Nor did he express any dismay or dissatisfaction at Milligan’s valuation, despite the final estimate amounting to only a fraction of what he had spent in total on individual volumes. He wrote to Milligan, “I am contented … with your estimate of price, if the committee should be so, or that they should send on valuers, fixing on your estimate.” In fact, Jefferson sold his library at a significant loss. Superintendent of the Patent Office William Thornton had advised members of Congress to offer $50,000, “for I have seen the Books, & knew them to be very valuable: that they ought not therefore to value them as Books in a common Library; for beside the learning & ability it would require to select the Books, they were not to be obtained but at very great trouble, great expense, great risk, & many of them not to be had at all.”

The Library Bill to purchase Jefferson’s library had its supporters and its detractors on both sides of the political aisle. Senator Goldsborough presented it to the Senate on November 28, which passed without amendment on December 3. After some delay, it finally passed the House of Representatives on January 26, but barely, with 47 percent of the House opposing the sale. Federalists in the House attempted to derail the bill. Motions to postpone the vote failed by a handful of votes. The proposal by Cyrus King, the representative from Massachusetts, that the Library Committee be authorized to sell the portion of the books that were, in their opinion, not useful or necessary for Congress, also failed. King, who had been reported by the National Intelligencer as being opposed to the general dissemination of Jefferson’s “infidel philosophy,” charged that Jefferson’s library “contained irreligious and immoral books, works of the French philosophers, who caused and influenced the volcano of the French Revolution.” He characterized the collection as “good, bad, and indifferent, old, new, and worthless, in languages which many can not read, and most ought not.” Echoing Federalist accusations that American imperialism and expansionism into British Canada were behind the Madison administration’s reasons for going to war, he charged that the transaction was a scheme in “true Jeffersonian, Madisonian philosophy, to bankrupt the Treasury, beggar the people, and disgrace the nation.”

Members of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia—who had at one time expected to inherit Jefferson’s scientific books—also expressed regret on hearing the news of the sale of Jefferson’s library to Congress. Jonathan Williams, representing the disappointed members and friends of Jefferson, wrote, “It can hardly be supposed, that in this Room surrounded by a Library consisting almost wholly of donations, with your almost animated Bust looking full in our faces, we could avoid expressing our regret that the rich collection of so many years of scientific research should be devoted to a political Body, where it cannot produce any benefit to them or to the World … Books as would adorn our Library and aid this Society in ‘the promotion of useful knowledge’ must there become motheaten upon the Shelves.” As far as we know, Jefferson, who had served as president of the society since 1797, did not respond directly to Williams’ letter. Instead, perhaps to avoid conflict (which would be characteristic of Jefferson), he wrote to the secretary, Robert Patterson, a week later to tender his resignation from the presidency. He argued that his longtime inability to travel to preside over the society’s meetings in Philadelphia was reason enough for him to vacate the position in favor of a successor, now that elections for office holders were imminent. He wrote, “Nothing is more incumbent on the old than to know when they should get out of the way, and relinquish to younger successors the honors they can no longer earn, and the duties they can no longer perform.” The society reluctantly accepted his resignation.

Moving the library to Congress

On January 30, 1815, Madison signed into law “An Act to authorize the purchase of the library of Thomas Jefferson, late President of the United States.” On February 5, while entertaining George Ticknor and Francis C. Gray, two gentlemen who had traveled from Boston carrying letters of recommendation from John Adams to “see Monticello, its Library and its Sage,” Jefferson received official notice of the purchase. Back in 1812, Adams and Jefferson had reconciled, and since then, they corresponded regularly. On hearing of the impending sale, Adams wrote, “I envy you that immortal honour: but I cannot enter into competition with you for my books are not half the number of yours.” Adams owned over 3,500 volumes, which are today preserved at the Boston Public Library.

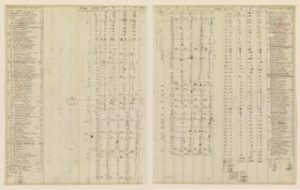

Smith wrote to inform Jefferson that the Secretary of the Treasury had been authorized to issue Jefferson with the sale proceeds of $23,950 in the form of Treasury notes bearing an interest rate of 5 and two-thirds percent. Jefferson, however, declined to receive any payment until his library had been delivered to Congress. He went to great lengths to ensure that everything associated with the sale was seen to be transparent and above-board at each stage of the transaction. He wrote to friends to collect the books he had loaned them, and carried out a detailed inventory of the books on his shelves at Monticello. He compiled a detailed tally for each chapter in his catalogue, along with a list of books that were missing from the shelf and another list of added titles that he had inadvertently omitted from his catalogue (fig. 3). The almost 72-year-old Jefferson informed Smith, “I will set about revising and arranging the books. this can be done only by myself … In doing it I must be constantly on my legs, and I must ask indulgence therefore to proceed only as my strength will admit.” Insisting that an agent verify that all was in order, he wrote to Madison, “I should wish a competent agent … with the catalogue in his hand, see that every book is on the shelves, and have their lids nailed on, one by one, as he proceeds … this is necessary for my safety and your satisfaction as a just caution for the public. you know there are persons both in and out of the public councils, who will seize every occasion of imputation on either of us …” He was not going to supply their political enemies with any fodder to accuse the sitting president or himself of wrongdoing.

Following a rigorous review of his library, Jefferson arrived at a physical count of 6,707 volumes, 220 more than Milligan’s original count of 6,487 volumes. Despite missing 83 volumes, this was more than offset by an additional 194 and a half volumes that had been omitted in Milligan’s count. Jefferson arranged for Milligan to procure some of the missing volumes at Jefferson’s own expense. Satisfied that there was no shortfall in the number of volumes due to Congress, Jefferson informed Treasury Secretary Alexander J. Dallas on April 18 that the books were ready for delivery and that he was ready to accept payment for them. Three and a half months would pass before Milligan realized that Jefferson had actually made a computational error in his tally sheet. While unpacking the books in Washington, Milligan discovered that Jefferson had inadvertently counted volumes twice, ending up with 251 more volumes than there actually were. Therefore the number of books delivered was over 6,500 volumes, which still exceeded the contracted figure of 6,487 volumes.

Uppermost in Jefferson’s mind was for Congress to have ready and convenient access to his library. His plan was to leave his books in the pine bookcases they were already housed in, and to simply have boards nailed over the bookcases to cover them. This way, his books could be transported to Washington, set up on end, and together with his catalogue as a guide, be immediately accessible for use by members of Congress. He calculated that his books and bookcases would weigh 27,000 pounds, and fill an estimated eleven wagons. Concerned that his fine bindings not be scuffed and rubbed excessively by the “joultings of the wagons,” Jefferson lobbied Madison to appoint Joseph Milligan to oversee their “careful and skilful packing,” and wagoner Joseph Dougherty, Jefferson’s former coachman during his presidency, to transport the books to Washington. These were the two men he felt would exercise the utmost care in the handling of his prized books. After spending nearly three weeks laboriously ordering his books, he proceeded to label each of them. According to overseer Edmund Bacon, Jefferson had Monticello slave John Hemmings make additional boxes, while his butler Burwell Colbert and Bacon packed the books up. Bacon recalled that James Dinsmore, who worked for Jefferson as a joiner, also helped, while Jefferson’s granddaughters, Ellen, Cornelia, and Virginia Randolph (then aged 18, 15 and 13 respectively) helped sort the books.

Between May 2 and May 8, ten wagons loaded with Jefferson’s books and bookcases set off from Monticello for their 125-mile journey northeast to Washington. As the last wagonload of his books left Monticello, Jefferson remarked with pride to Samuel Harrison Smith, “ … an interesting treasure is added to your city, now become the depository of unquestionably the choicest collection of books in the US, and I hope it will not be without some general effect on the literature of our country.” Two hundred years after the sale, Jefferson’s legacy is still celebrated as the founding collection of the Library of Congress.

The books arrived in Washington six days later. They were set up on the third floor of Blodget’s Hotel at Seventh and E Streets, which served as the temporary Capitol for members of Congress (fig. 4). Due to illness, Milligan did not begin unpacking the library till the second week of July. When he finally completed the task on July 24, he happily reported to an anxious Jefferson a week later that the books had arrived without suffering any damage.

Organizing knowledge, structuring a legacy

In the way Jefferson organized his library and ordered it for use, we see a man who sought to shape his legacy, and who viewed the library he sent to Washington as a statement of the values he had espoused throughout his life as a politician and statesman. In briefing the newly appointed Librarian of Congress, George Watterston, Jefferson described the immense effort he had expended to order and document his collection exactly the way he intended Congress to have it. He stipulated, “You will receive my library arranged very perfectly in the order observed in the Catalogue.” Jefferson organized his library by subject, based upon a scheme he had adapted from Francis Bacon’s Advancement of Learning and Jean Lerond D’Alembert in the Encyclopédie, as well as chronologically. He divided human knowledge into three major groups, namely history, philosophy, and fine arts, in accordance with Bacon’s “faculties of the human mind,” namely memory, reason, and imagination. These were in turn subdivided into forty-four chapters or subjects. He enjoyed the “peculiar satisfaction” of seeing at a glance all the books he possessed on a particular topic. Books were arranged on the shelf by size, while the arrangement in his manuscript catalogue was “sometimes analytical, sometimes chronological, & sometimes a combination of both.”

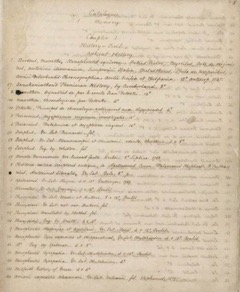

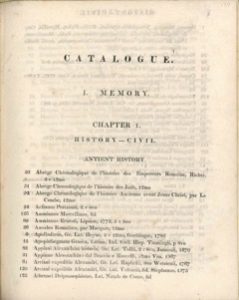

Jefferson’s manuscript catalogue was sent to Washington along with the books. It ended up being retained by Watterston as his personal property, and unfortunately is lost. In 1823, Jefferson had his personal secretary and future grandson-in-law, Nicholas Philip Trist, recreate his catalogue. This 1823 catalogue, which survives today at the Library of Congress, is the closest surrogate we have for Jefferson’s original listing of the books he sold to Congress (fig. 5). From Jefferson’s manuscript catalogue, Watterston produced a print catalogue entitled Catalogue of the Library of the United States, which turned out to be a disaster in Jefferson’s eyes. Watterston had taken the liberty of alphabetizing the titles within each chapter, thereby upsetting Jefferson’s carefully ordered entries (fig. 6). His arrangement reflected his understanding and particular method of organizing what enlightened individuals of his time regarded as “useful knowledge.” When Jefferson eventually received copies of Watterston’s print catalogue in late January 1816, he complained to Joseph C. Cabell: “The form of the catalogue has been much injured in the publication: for altho they have preserved my division into chapters, they have reduced the books in each chapter to Alphabetical order, instead of the Chronological or Analytical arrangements I had given them.” An entire month passed before Jefferson wrote to Watterston to acknowledge his receipt of the catalogues. He gave no hint of his displeasure, except to remark in passing, “you ask how I like the arrangement within the chapters? of course, you know, not so well as my own;” and then with a hint of sarcasm added, “yet I think it possible the alphabetical arrangement may be more convenient to readers generally, than mine …”

In December 1818, the Library of Congress moved from Blodget’s Hotel back to the north wing of the Capitol building. Jefferson heard news of the move from Joseph Milligan, who had been engaged in the move. In the attic story on the west side of the north wing, conditions were cramped. Later, in August 1824, the library moved to new, spacious quarters in the central portion of the restored Capitol building designed by Charles Bulfinch. Jefferson continued to take an interest in the Library of Congress after the sale. In early September 1820, he forwarded to Watterston and the congressional library committee a catalogue of books relating to America that he thought might be useful in further expanding their collection. He even took the trouble to mark the books he knew they already had so it would be clear to them which ones they did not yet have.

Congratulating Jefferson after the sale of his library had been finalized, William Short expressed relief that Jefferson’s library was going to stay intact as a collection. He wrote, “It gave me great pleasure to see that your valuable Library was to be secured & forever kept together.” Little would he know that thirty-five years later, on Christmas Eve in 1851, a fire that began in a faulty chimney flue in the Capitol would destroy much of the Library of Congress’s 55,000-volume collection. Two-thirds of Jefferson’s books were lost. Today, Jefferson’s library has been recreated in a permanent exhibit in the Thomas Jefferson Building at the Library of Congress, consisting of the more than 2,400 surviving original volumes, along with replacement copies.

Money for debts, money for books

Of the sale proceeds of $23,950 he received in the form of treasury notes, Jefferson designated $10,500 to William Short, $4,870 to John Barnes to settle Jefferson’s outstanding debt to General Tadeusz Kosciuszko, and the remaining $8,580 to himself. Short had been Jefferson’s private secretary in Paris when Jefferson was minister plenipotentiary and then minister to France from 1784 to 1789. The $10,500 was to pay off three bonds totaling $10,000 and the accumulated interest Jefferson owed Short. In 1798, Kosciuszko had granted Jefferson power of attorney over his American assets. The $4,870 was a loan of $4,500 with interest that Jefferson had loaned himself from the general’s assets to pay off notes he owed to the Bank of the United States in 1809. In settling his obligations, he chose to clear these two outstanding debts and a number of other smaller ones. Yet he did not settle others but chose instead to buy books for his replacement library at Monticello.

Even as he was organizing the transfer to Washington, Jefferson had begun planning a replacement library. In late February 1815, he wrote to the American consul in Paris, David Bailie Warden, “I have now to make up again a collection for my self of such as may amuse my hours of reading.” He wrote to John Vaughan to enquire after depositing funds in London, Liverpool, Paris, and Philadelphia to fund his anticipated book purchases. In June, after his books had left Monticello, Jefferson declared to John Adams, “I cannot live without books; but fewer will suffice where amusement, and not use, is the only future object.”

In this abbreviated account of the 1815 sale, we see how Jefferson used the library he sold to Congress as a self-fashioning project to shape his legacy and the way he wished to be viewed by posterity. Like the papers and personal correspondence he left behind, Jefferson considered his library—its collection scope, the individual titles and editions, its meticulous organization, and its breadth and depth of “useful knowledge,” as a reflection of what he stood for, a symbol of how he wanted to be perceived by his peers, his political opponents, and the public. In offering the library to the nation at significant financial loss, Jefferson was acting in a manner he perceived as consistent with republican virtue and self-sacrifice. He viewed the transfer of his library as crucial in ensuring the survival of the American experiment and its democratic government, and an important step in building the nation. It was also an opportunity to profoundly shape the country’s intellectual, social, and political future, while shaping his own public legacy.

How, then, do we explain family descendant Sarah N. Randolph’s assertion over fifty years after the sale of the library, in her 1871 biography, that Jefferson sold his library solely out of dire financial necessity? It is useful to realize that Randolph’s statement was part of a consistent narrative, promulgated by Jefferson descendants shortly after Jefferson’s death in 1826, that long years of dedicated public service had essentially impoverished the Founding Father and his family. Randolph’s account of the 1815 sale was effectively a continuation and reflection of this family narrative, one in which losing the library was a pointed symbol of the terrible personal cost of Jefferson’s public service, and more important to highlight than the public legacy he sought to shape while meeting pressing financial needs.

Further Reading

The Jefferson letters cited are published in volumes 7-9 of the Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement Series (Princeton, N.J., 2010-2012), and available online via Founders Online. Sarah N. Randolph’s biography of Jefferson is The Domestic Life of Thomas Jefferson (New York, 1871).

For more on the 1815 sale, see Kevin J. Hayes, The Road to Monticello: The Life and Mind of Thomas Jefferson (New York, 2008); Carl Ostrowski, Books, Maps, and Politics: A Cultural History of the Library of Congress, 1783-1861 (Amherst, Mass., 2004); James Conaway, America’s Library: The Story of the Library of Congress, 1800-2000 (New Haven, Conn., 2000); Lucy Salamanca, Fortress of Freedom: The Story of the Library of Congress (Philadelphia, 1942); and William Dawson Johnston, History of the Library of Congress, Volume 1, 1800-1864 (Washington, 1904).

This article originally appeared in issue 16.4 (September, 2016).

Endrina Tay is associate foundation librarian for technical services in the Jefferson Library at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello in Charlottesville, Virginia. She heads the Thomas Jefferson’s Libraries Project, based at Monticello.