Cassie: I’ve often thought about how Founding Friendships would look if I had written it in the style of my current book, although I still have never figured out how I could write it chronologically rather than thematically. I didn’t have a clear thread of how friendships changed over time in the early republic, but I did have sets of themes that my evidence cohered around. How did you structure Christian Imperialism?

Emily: The structure I ended up with really reflects the argument I was making in the book and was a big revision from the dissertation. The dissertation actually took on more of a narrative arc—maybe that’s why I really wouldn’t rewrite the book as a narrative now! The dissertation had more of a narrative arc as a religious history and focused a lot on the question of how missionaries and their supporters defined what was “morality” and what was “politics” as they evangelized in a world of empire. When I thought about how to turn the dissertation into a book, I wanted to do a better job of centering the questions about empire that had gotten me so excited. To do that, I restructured the chapter outline a bit to allow each chapter to be more of a case study of different types of imperialism. This meant that I dropped one chapter in the dissertation about slavery that I need to come back to one of these days, but I don’t think I could have made the argument I wanted to make in a more narrative style. I still really like the structure I used there, and I couldn’t change it without having to really change the heart of the book.

How did working on this book lead you to your second book? What did you learn through that process that has influenced what you’re doing now?

Emily: I love talking to folks about this question, because there are so many different journeys from the first book to the next. Some folks really seem to want to do something completely different; others have a very clear progression from one to the next. It took me some time to decide on which route I wanted to go in. I had actually received a warning from one mentor that I might not want to do the next book on missions—lest I get stuck in a “missionary ghetto.” But I ended up taking the advice of another mentor that it could make a lot of sense to build on what I already knew to position myself as one of the experts in this field. And I’m still finding lots to say about missionaries and American foreign relations, so I’m okay continuing to work on them for a bit longer. In the end, I wanted to answer some questions that I had received at conferences about missions and policy, which I didn’t get to at all in the first book. That was the springboard for Missionary Diplomacy, the book I’m finishing up now.

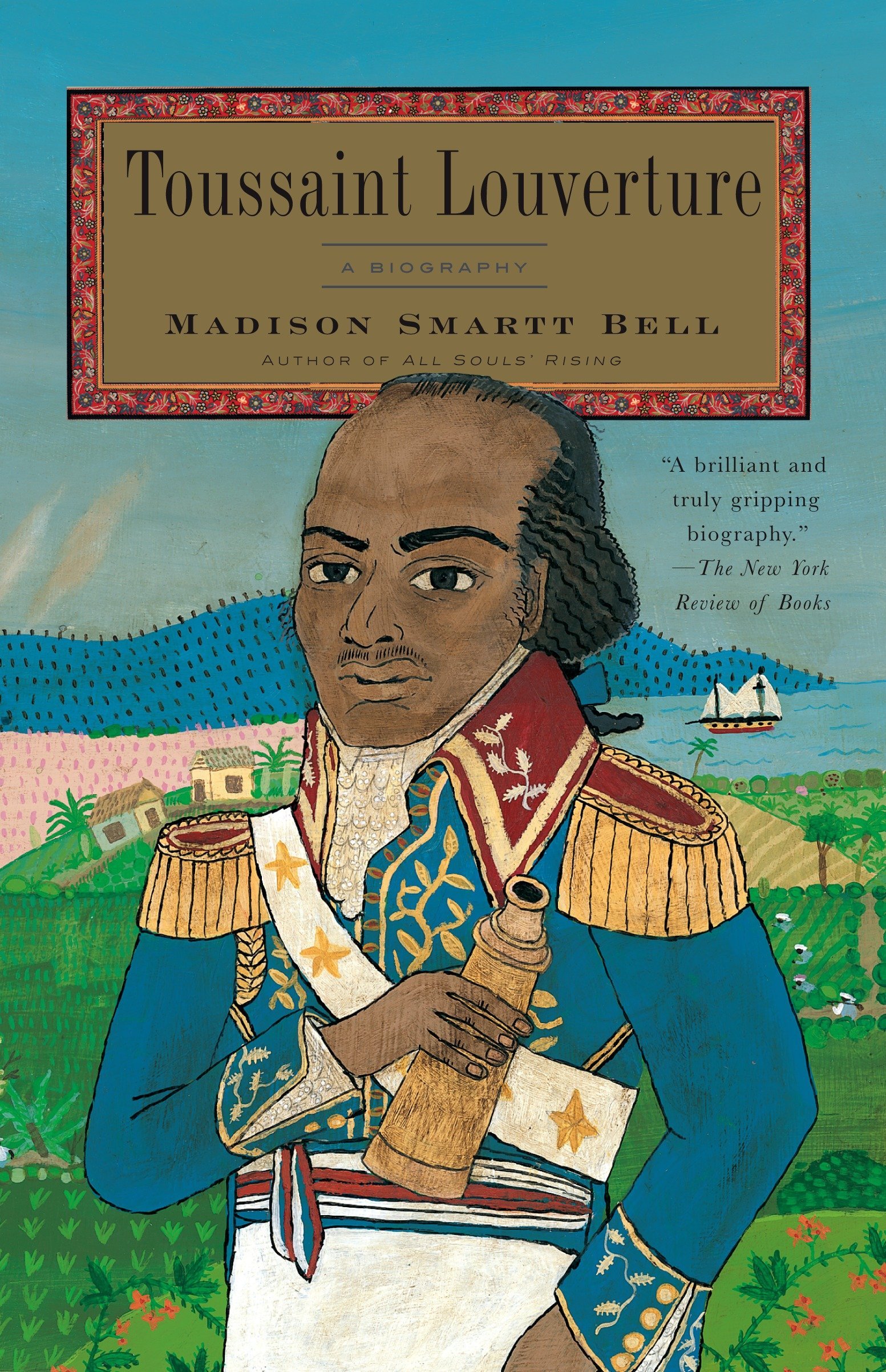

Cassie: I definitely had a different journey to my second book, because I have shifted to writing a biography of a family. I’m still focused on early America and the intertwining of relationships and power, but otherwise this is a very different book. Nonetheless, I came to it from the first book; I read some correspondence of the people I’m now writing about, George Washington’s step-grandchildren, in the research for Founding Friendships. I really enjoyed digging deep into the stories of some of the people I wrote about in the first book, and I wanted to immerse myself in just a few individuals’ stories. First Family tells the story of four rather eccentric but at the time very famous siblings from the American Revolution to the Civil War, and while the research for it took a decade, it’s been so much fun.

Ultimately, books are static, material things. As historians and writers, we’re always changing, and so is the field of history. We can shift approaches and apply lessons learned to the next book, but only in the rare cases of a second edition of a book does the author get to add later reflections to the physical text. We hope this conversation spurs more authors to find ways to remain in dialogue with their books and critics.

This article was originally published in September 2022.

Cassandra Good is associate professor of history at Marymount University in Arlington, VA. She writes and researches on politics, gender, and culture in the early American republic. Her first book, Founding Friendships: Friendships Between Men and Women in the Early American Republic, won the Organization of American Historians’ Mary Jurich Nickliss Prize in U.S. women’s and/or gender history in 2016. Her next book, First Family: George Washington’s Heirs and the Making of America, is forthcoming from Hanover Square Press (an imprint of Harper Collins) in 2023.

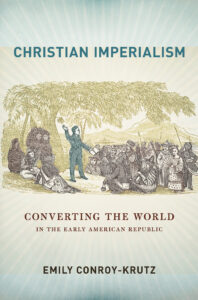

Emily Conroy-Krutz is associate professor of history at Michigan State University and the author of Christian Imperialism: Converting the World in the Early American Republic (2015). Her writings on religion, reform, empire, and gender can be found in the Journal of the Early Republic, Early American Studies, Diplomatic History, and several edited volumes. Her next book, Missionary Diplomacy: Religion and American Foreign Relations in the Nineteenth Century, is forthcoming from Cornell University Press.