Author’s Note:

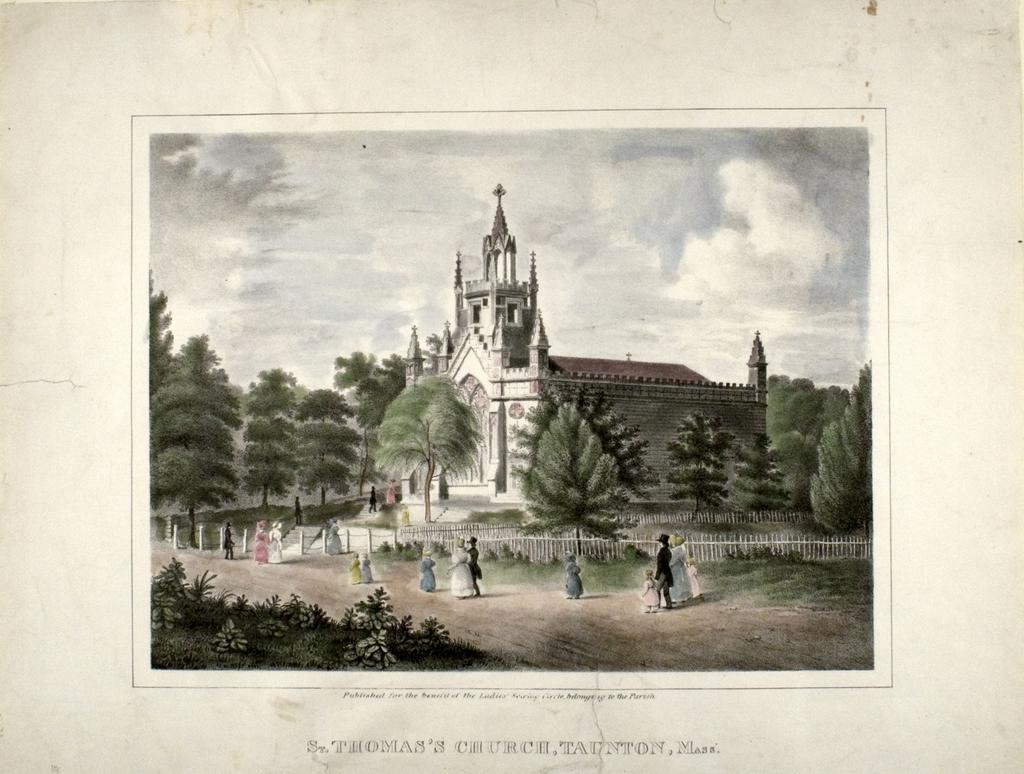

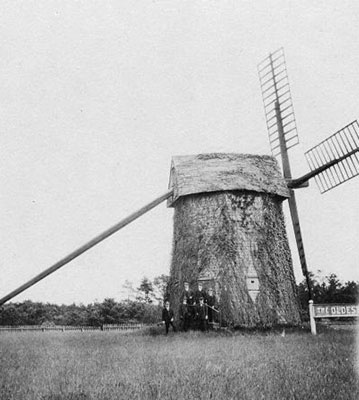

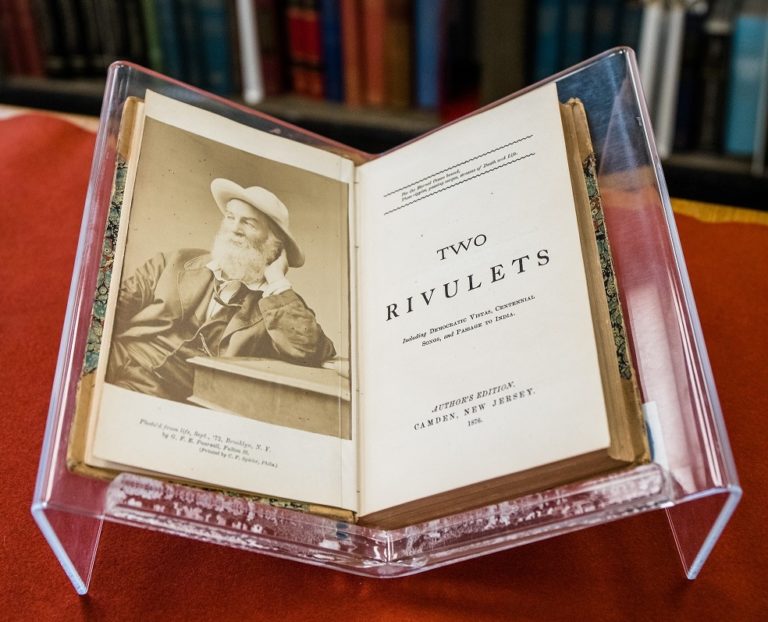

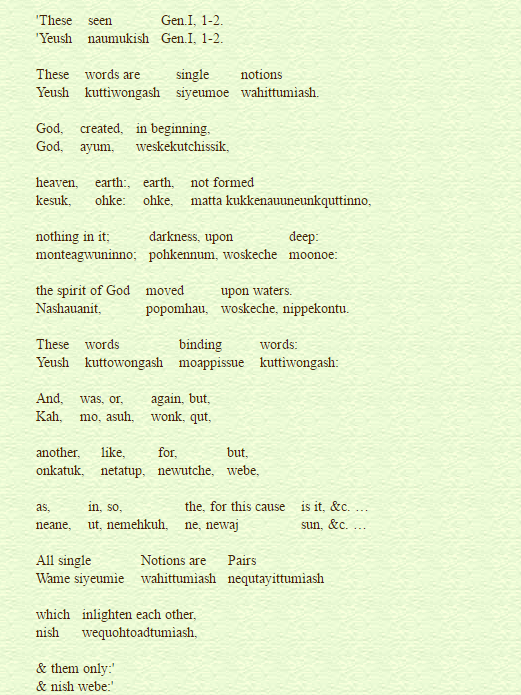

As I hope will become readily apparent, The Hungry Eye is a work of historical fiction. Some of its characters and incidents are pulled from the historical record–most particularly, the dueling “special artists” Peleg Padlin and Little Waddley. Their misadventures while touring New York’s netherworld originally appeared in an 1857-58 series of articles in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper written by New York Tribune reporter Mortimer Neal Thompson. That the pseudonymous pictorial reporters stood in for Leslie’s staff artists Sol Eytinge Jr. and a very young Thomas Nast should not be of concern to the present-day reader. Moreover, the mystery at the heart of The Hungry Eye, which entangles these and other characters and the constellation of their relationships, is my own invention. Much of what transpires here (and in the ensuing installments, which will appear in Common-place monthly between January and April) is utterly fantastic–and yet it also, I believe, remains true to the history of a specific time and place.

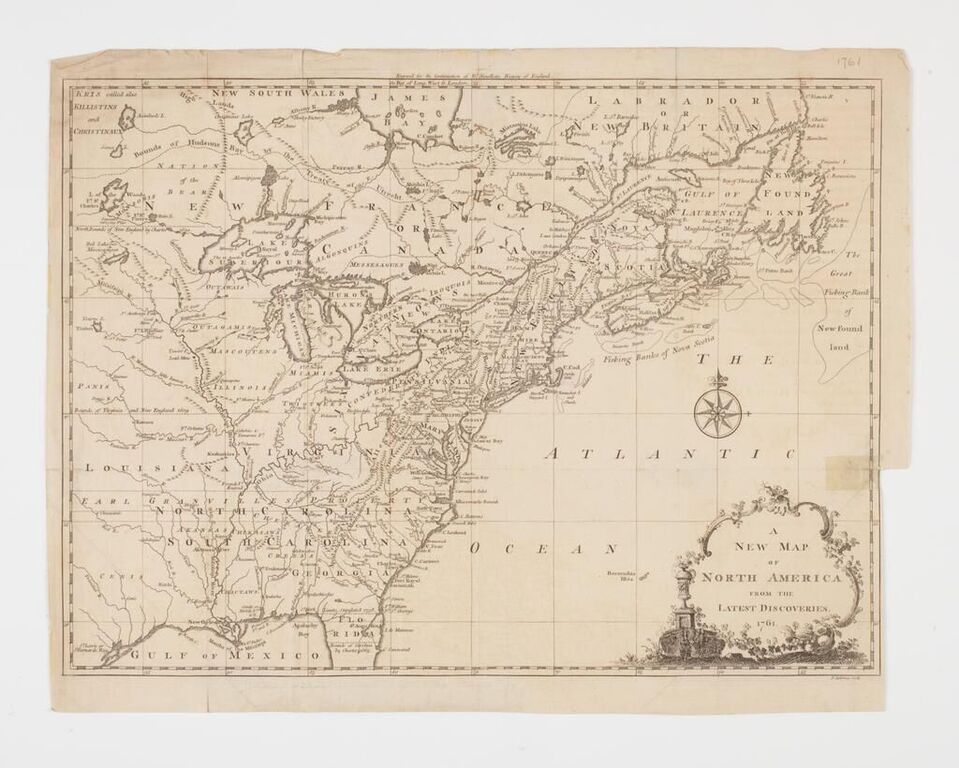

While I originally conceived of The Hungry Eye as a conventional novel (at least in the sense that it would end up as a tactile book printed on paper with a spine available for cracking) the chance to emulate the once ubiquitous format of serialization was hard to pass up. And wedding an older episodic approach to the still inchoate medium of the World Wide Web offered an intriguing narrative challenge. Aside from requiring some reconfiguring of the story’s structure to accommodate the start-and-stop pacing of extended and intermittent reading, I’ve tried to work with the Web to intermingle the visualization of the past–which plays a prominent role in the plot–with the telling of the story. That said, you won’t come across any state of the art programming here: what I’ve tried to do is enhance the reading experience on the Web, not replace it.

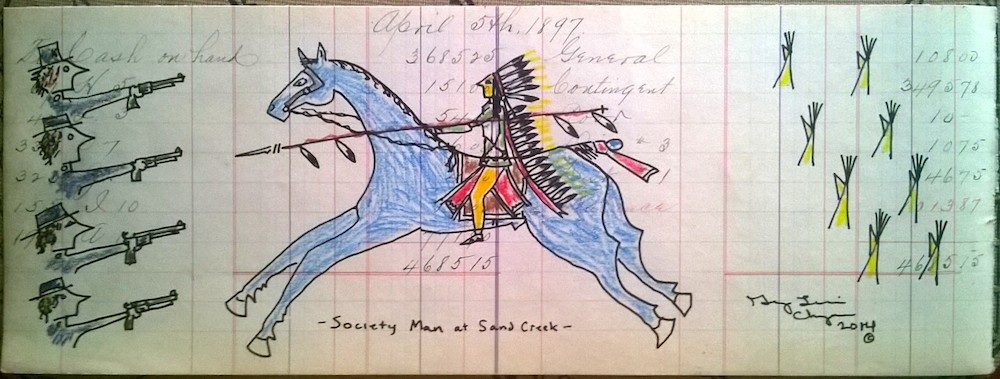

All original artwork © 2001 Joshua Brown.

Episodes 1 – 3 of The Hungry Eye first appeared in Vol. 2 No. 2.

Chapter VIII After the terrier cornered the rat, all Padlin saw was a commotion of claws, paws, and teeth. The dog’s rear tensed, muscles sheening through the short hair, and his head scooped up the rat, a sooty, glittering, legs-skittering sandbag in his mouth. The dog’s lower jaw snapped up, a hard click, and the rat’s head separated. Hitting the ground nose-first, it bounced and then rolled erratically across the floor until it glanced off of Waddley’s shoe. “Blast!” Waddley shouted. He bent down, gathered a handful of straw from the floor and wiped off the bloody smear. Still in a crouch, he eyed the rat’s head. He pulled out a small pad from his jacket pocket and began quickly working out a sketch. A black egg shape in the foreground, the terrier behind with the dangling carcass between its jaws. “Get beside your dog, please,” Waddley said, and the trainer obediently ambled up to his beast. He struck an awkward pose, bent over the animal, one arm extending his battered top hat in a Bowery-show stance. The terrier growled. “The dog’s name?” Waddley asked, his pencil forming the trainer, expanding his nose, shortening his arms, clipping his waist. “Deadeye,” the trainer answered. “He hates rats. Sees one, won’t stop till he knows it’s dead. Never misses.” “Deadeye,” Waddley repeated, scrawling the name under the scene. Padlin stood by, hands in his pockets, bone weary and amazed at his colleague’s single-mindedness. Waddley. His partner. His nemesis. It had been bad enough when Quidroon had allowed the little bacon-faced runt to steal his sketch. It was now so much worse, Waddley forced upon him, his own personal leech. No, vampire. A much more appropriate image. “What the hell are you doing?” Quidroon had demanded, interceding, while Waddley gazed anxiously at the block wavering over his head. With Quidroon’s shout, the murderous vision dissipated in Padlin’s head. Lowering the block, he said: “Her face.” “Goddamn it, man, whose face?” “The girl. The one in the morgue.” In the space of that brief, bloody reverie, as Padlin contemplated the impact of woodblock on skull, he had come to a realization. If he couldn’t master the girl’s face, if there was no hope, he had to bring the story to a close in another fashion. The East River morgue, the Points dog hunt, the dead girl’s mad quest and demise–they all led to Sportsmen’s Hall. Kit Burns’s dog pit was the only place to go. So, heart pounding, Padlin reached down into the limited resources of his invention and began to talk. It was a creative loquacity born of desperation and, most probably, sleeplessness. He told a story about a dead, cholera-ravaged girl, a girl he’d glimpsed in the Points, a notorious aficionado of the dogfights, surely struck down by her vices and the corruption issuing from the pits. Quidroon heard “dogfights,” he heard “epidemic,” and, undoubtedly, an attractively grotesque tableau floated into his mind, suitable for a double-page engraving in the heart of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. He dispatched Padlin to Kit Burns’s waterfront dive. But Padlin’s insubordination could not go unanswered: “Yes,” Quidroon smirked, “go to Sportsmen’s Hall. Go tonight. But go with Mr. Waddley by your side.” Sportsmen’s Hall, it turned out, was much less grand than its name implied: all makeshifts and mazes, narrow passages harbored by rude planks leading into large and small cubicles, straw strewn all over the floorboards. The foulness of the air was a palpable thing, a reek that stunned and then settled upon the senses, a weapon and then a shroud. The itchy sting of the straw couldn’t hide the smell of breath wretched with alcohol’s ravages, breath clotted with blood and meat. Smells of shadows, gaslight, and night. Padlin much preferred the morgue. “Padlin.” Waddley was grimacing up at him from his crouch. He adjusted his spectacles, a fidget to cover what Padlin was sure was a sneer. “I, of course, bow to your long experience in the field.” Waddley’s small, pearly teeth momentarily glistened. “But, Padlin, don’t you think it would be wise to sketch as much as possible before someone here takes exception to our presence?” They exchanged stares, Waddley’s glasses upturned to hat-hooded Padlin. “I’m not here to sketch,” Padlin said and turned away toward the rumble and clout of the dogfight. He would draw nothing tonight. He would exert not one smidgeon of pain or skill upon recording the scene or its actors. There was no point. Quidroon would never accept any of Padlin’s sketches. Waddley had been dispatched as the instrument of his punishment, but Quidroon would reserve the final, fatal stroke for himself: the denial of the one desire he was certain Padlin cherished. Except, Padlin thought as he walked through the passageway, rounding the jagged turns that moved from gaslight to shadow, gaslight to shadow, except Quidroon was on the wrong track. Padlin no longer pined for the morgue sketch–or any sketch, for that matter. He had a different plan. In Padlin’s exhausted mind, it bore no name but possessed a form–but not even that exactly. It was a sensation, one composed of relief and a light feathery brightness, a vision that grew in breadth and somehow became a landscape of deliverance over which Padlin could soar. He could do nothing about his mother’s pinched deathmask, but Padlin was determined that the girl would not haunt him as well. Padlin would leave Sportsmen’s Hall only when he knew he would never, never think about her again. Driven forward by this inexact ambition, Padlin stepped into the heart of Kit Burns’s Dog-paradise, the packed and heaving fighting amphitheater. Seventy-five, one hundred, a horde of men (peppered with a selection of the establishment’s whores) squatted on tiered bleachers, bodies cascading down to a low plank fence. Padlin was greeted by their vocal flatulence, full-throated and unreserved, bellowing bets and threats into the pit. He stopped in the narrow passageway between the bleachers, his head even with the top seats, arses squirming to his right and left. Listening to the encouragement impossibly mixed with abuse, he watched the two creatures wriggling in the dirt. The dogs tore at each other, wrapped in a tight ball. They rolled, legs occasionally flailing, slashes of movement starkly outlined in the glare of a four-headed gas jet perched over the pit. Just beyond their embrace, their handlers pawed the ground, growling and barking on their hands and knees, held at bay by double semicircles etched in the dirt that demarcated their sides. In the pumping noise, Padlin suddenly realized one sound was missing. The room was filled with human rants. The handlers yelped in their corners. But the dogs kneaded and tore one another in absolute silence.

Suddenly, the animals broke apart, a bloody latticework stretching from their mauled heads until it snapped in a splutter of gore. The bleachers shuddered with the crowd’s stamping feet. Swinging cracked top hats and crushed caps, spurting shrill whistles, the spectators hollered encouragement. Get ’em, Daisy! Anodyne the bastard now, god damn it! Rabbit! Her leg, crack her leg! Rabbit! Rabbit, go for her throat! Her throat, y’fucking brute! But Daisy and Rabbit were having none of it; they wobbled at either end of the pit, snuffling at the dirt, wearily eyeing one another and ignoring their handlers who frantically gesticulated and screeched behind them. Both dogs’ muzzles were ripped and bleeding, the smaller one with no ears–Daisy, Padlin guessed–exhibiting a nasty gash across her rippled back. “No heart. They don’t have no heart.” A boy peeked up from under the bleachers. A boy with a caked head of hair and crusty upper lip who Padlin, amazingly, at first could not place. “The fight’s over. You’ll see.” Padlin recognized the kid and a cold flash ran through him, a piercing sense of panic. He didn’t move, he just gazed down at the boy. Padlin’s petrification seemed to reassure the boy. He didn’t work his way into the aisle, he didn’t want to get too close to Padlin just yet. But his eyes were fixed on the pad protruding from Padlin’s jacket pocket. Daisy and Rabbit hadn’t moved either. The room was rocking with miserable explications and enraged curses. “Time, gentlemen!” A stone–no, it was some fruit–arced into the pit and scattered the dirt between the dogs. Each startled backwards into the arms of its handler. The men immediately set to blowing on the dogs’ trembling hides, administering frenetic slaps alternated by caresses. They nuzzled the bloody bodies, pressed their faces against the curs’ shorthaired skulls, exhaling remonstrances and reassurances into the ruined ears. “Ready!” shouted a man dressed like a Broadway swell. A jewel twinkled from the scarlet cravat puckering up out of his vest. His bearing, though, was all waterfront: his short-waisted slab of a torso designed to absorb bare-knuckle assaults. He bent over the pit wall, cupped his hands around his mouth. “Go!” The handlers threw the dogs in the turf, walloping their hindquarters. Daisy and Rabbit didn’t move. Groans and oaths poured down but the two curs just wobbled in place. The referee dramatically pulled a watch from his vest pocket. Disgust crumpled his long mouth, an upside-down “u” exaggerated by a goatee that covered his jaw like black ink. He turned to his right, he turned to his left, he turned about, eyes squinting in the kind of gestural dare usually displayed by villains on the blood-and-thunder stage. “Stalemate!” the referee pronounced. He turned back to the pit and adamantly folded his arms against his chest as the abuse fell. The handlers hurriedly retrieved their exhausted beasts and trotted out of the ring, shielding the shamed contenders from the crowd’s wrath. “What did I tell you?” The boy slowly straightened up, sidling his way out of the bleachers, his back grazing the rough wood construction. He continued to stare at Padlin’s pocket. Then he looked up under the rim of Padlin’s hat, into his eyes, and a canny expression jittered the boy’s cheeks. He looked like an apprentice sharper, trying to perfect a three-card monte smile. “If you draw me a picture,” he said–nervousness suddenly undermining his brashness, one dirty hand picking at the tatters of a shirtsleeve–“if you draw me a picture, then I won’t have to tell Kit about you.” He was already retreating back under the bleachers, head collapsed into the bony shelter of his collarbone, when Padlin answered, calmly, barely audible in the hubbub: “Go ahead. Tell him about me.” A moment’s hesitation, a smudge of confusion spreading across the boy’s blunt features. He quickly recovered himself, though, forever adaptable thanks to the slipperiness and serendipity of the Points. “I will.” Padlin turned away to gaze down at the empty pit. “I’ll tell Kit about how you sent Mollie Maloney looking for him. Oh,” the boy’s canny smile shivered with effort, “he ain’t going to take kindly to that.” The mention of the name, the long-unknown caption to place under the terrible engraving, the title that would complete the coroner’s report, the enunciation of Mollie Maloney burst something in Padlin’s head: a calcium-white cough of light that sapped his will and determination. Padlin’s mind became cluttered with Mollie Maloney’s uncaptured features, static sketches fluttering across his gaze, obscuring his vision, making everything before him unfocused, without depth. Suddenly weary, Padlin barely noted the increased uproar of the crowd. Then the referee vaulted over the fence and landed heavily in the center of the pit. The referee paused to return his shining top hat to its previously jaunty angle, he tugged at the tails of his jacket. He raised his arm, the hand dipping from the weight of the rings adorning every finger. Padlin heard but did not follow the referee’s words, his shout-shocked voice rasping: “Gentlemen! The main contest is at hand!” The raucousness answering this pronouncement drowned out whatever the kid said next. Padlin caught the high-pitched timbre, a sharp point piercing here and there through the crowd noise, pinpricks that admitted leaky chirps. “The contenders,” the referee bellowed, pressing down the hubbub, “the two opposing champions, have been properly prepared for their match. This will be a clean, fair fight, gentlemen. Kit Burns guarantees that.” His chest puffed balloon-like out of his jacket, the referee paused to allow the thunderous response (which included a fair share of derision). “All the rules have been observed,” he continued. “The contenders are equally matched. Weighed in one hour before this match at twenty-eight pounds each, ears cut, tails on. In the last half-hour, corners was determined by the toss of a coin and the champions then was bathed according to Bandbox rules. One,” the referee popped a finger out at the crowd, “washed in hot water with soda and Castille soap. Two,” he enthusiastically forked the fingers, “washed in fresh cow’s milk. And three, the all-important test. The red-pepper test, gentlemen! Each trainer was permitted a taste of the opposing champion. And, as a final, incontestable test, I, Kit Burns, licked each dog myself!” Cheers and oaths tumbled from the bleachers. Padlin stared at the blocky figure in the fighting ring. Recording the thick torso and foreshortened legs upon a mind’s-eye sketchpad, Padlin worked the shapes and relationships into cartoon exaggerations: Kit Burns. Padlin felt none of the dread the name had previously evoked; the amorphousness of his fearful imaginings, a vaguely formed yet threatening ogre, had gained flesh and lost its menace. “And, gentlemen, gentlemen.” Burns’s hands tamped down the racket. “Let me just say, each of them, oh, gentlemen, each of those two marvelous beasts tasted soooo good!” The place clamored in appreciation, the bleachers palpitating as boots beat a myriad of tempos upon the planks and arses bounced up and down on the rough seats. “I’ll tell him. I will!” The kid’s words abruptly emerged. Padlin peered around, catching the boy crouched farther back underneath the bleachers. He was barely visible in the gloom. “I will,” he repeated and, still receiving no response, he said: “I’ll tell Kit you was the one sent her. I’ll tell him you was the one that tried to steal Butts.” Burns whistled, thumb and forefinger poked in the corners of his long mouth. “Place your bets, now’s the time!” He composed his stance, squaring his bulky shoulders, hands propped against his crotch like a preacher ready to receive the converted. “Gentlemen,” he intoned, “I give you, hailing from Philadelphia, Moyamensing’s own magnificent,” (Burns dramatically swept his top hat from his head right toward Padlin), “Crib!” As the room resounded with cheers and hisses, a man brushed past Padlin, heading for the pit. He had the rolling gait of a sailor, one arm levered out to counterbalance the weight of the blanketed bundle burdening the other. “Crib’s opponent,” Burns shouted, “is the Bandbox’s pride. I give you, gentlemen, the amazing, never-beaten and forever unbeatable–Butts!” An approving roar overawed the smattering of hoots and hisses, and Padlin found himself hurtling down toward the fighting ring. Butts. Padlin stumbled into the pack of bettors clustered at the waist-high fence. The dog sketches flapped within his head, canine cartoon after canine cartoon, types of dogs but no dog in particular. Padlin shoved through the packed bodies, his hat smacked right, left by the tangled foliage of outstretched arms and the thrusts of fists clenching cash. Butts, a belligerent fart of a name, repeatedly popping in Padlin’s ears. She had called him Jakesy.

Chapter IX Butts was borne into the ring by a skinny man–barely that, actually: a spindly sketch of a man, his legs seeking purchase under the weight of the heavy package in his embrace. Swathed in a blanket, snout bound in a leather muzzle, only the gleaming tip of Butts’s nose was visible. The dogs were placed in the powdered semicircles demarcating their sides. The trainers–the sailor and Kit Burns–removed the blankets and muzzles. Each knelt behind his dog, enveloping the beast in a tight embrace, murmuring words at the quivering back. The skinny man-boy, freed from his burden, stepped back over the fence and assumed the stance and attitude of the proprietor of Sportsmen’s Hall. His imitation was a poor caricature of his boss’s brawny presence, his hands lost in the cuffs of a shirt meant for someone broader. Nevertheless, the din in the room quickly petered down to a convulsive mutter. The boy maintained his pose, relishing the moment of command. Flapping his hands out of the capacious shirtsleeves, he brought them to his mouth, paused another instant, and then piped out: “Release!” The dogs seemed to explode out of their restraints, two projectiles flying into the air toward the center of the pit. They met under the gas jets and, leaving a trail of spittle and hair, collapsed in an entangled, heaving heap onto the dirt. Padlin gripped the upright boards. He tried to catch the slashing motion, to make out Butts amid the flying dirt and kicking limbs. The dogs broke apart. They snorted and snuffled, hackles raised, dancing sideways, eyeing each other. Butts, Padlin guessed, was the one with the peculiar brindled hide. Pale streaks disrupted his deep-brown hair in a manner that reminded him of welts left by a lashing. Otherwise, Padlin could only distinguish general movement and fractured details: the dog’s mouth contorted in a snarl, his sideways shuffling, his earless head skulking below his shoulders. The other dog, Crib, had the flat, exaggerated features of a harlequin. Long, puffy eyes hunkered on either side of a mashed muzzle, flews intersecting at a dry freckled nose. Crib stopped, impressive in his stiff stance, muscles roped under the speckled hide, hindquarters and testicles trembling. His snout wrinkled revealing ivory fangs, the long canines jabbing into the soft skin of the lower lip. Crib growled, a low scraping sound that filled out the crowd’s hoots and calls. Padlin thought of a piece of slate drawn across cobblestones. Butts halted. He was a finer specimen than Crib, sinewy like him but more subtly formed, a delicate watercolor to Crib’s rough pencilwork. His skull was long, with deep brows over a short, triangular muzzle that truly suggested the bridge of a nose. Butts’s face made Padlin suddenly doubt the rules of physiognomy he shared with his peers. The artist was taught to locate the animal traits beneath human countenances, creating a sketch that teetered on the cusp between Homo sapiens and the lower creatures: truer to life than the mundane appearance of the subject himself. But if Padlin ever tried to draw Butts, he would have to reverse the process, chiseling God’s greatest work out of the irrational and savage. Butts’s pelvis rose, his tail arched downward. Crib seemed to check his opponent’s move, the growl rising slightly in pitch. Butts snarled and a rumbling undertow emerged from him, tugging at Crib’s higher rasp. “There goes the bastard again,” someone said in the crush of men about Padlin. “Watch him, now. Watch what he does.” A chorus of affirmations followed, bereft of the usual salty skepticism and insult. And when the responses diminished, there was nothing more: the room fell silent, but for Crib’s keening and Butts’s basso retort. Two dogs were in the pit, but every gaze seemed to be fixed on Butts. And then Butts’s growl changed. The rumble constricted and became throatier, a tenor. It began to warble. The warbling quickly became a vibrato–but a vibrato cut unevenly–like, Padlin grasped at the sound’s effect, like the bobbing current of words in a mellifluous voice. Padlin glanced over at Crib, whose grimacing clown face was cocked in puzzlement. Crib maintained his snarl, but his heavy brow was furling, nervous waves beating at his eyes, as if he was furiously exercising the slim resources of his wit to deal with this unpredictability. Butts’s voice seemed to grow more focused, the vibrato now regular, like a phrase repeated, sing-song, over and over again. His muzzle twitched to the enunciations, his face relaxing, losing all signs of wildness or wrath. Crib visibly relented. Careful to keep his canines exposed, he nevertheless was sufficiently confused to lower his hindquarters to the ground. He cocked his head quizzically and his tongue nervously lapped at his flews. Suddenly, shockingly, soundlessly, Butts sprang. He landed on Crib. His jaws snapped around the startled dog’s nose. Crib frantically pawed backwards, trapped under the brindled dog. Blood spurted from around Butts’s mouth. “Devil dog!” The exclamation was nearly lost in the pandemonium. The crowd hollered ecstatically, emitting looping whoops as the blood splattered onto the dirt. Padlin was no innocent. As an artist-reporter he had delved into the wretched underlife of the city. He had inspected the dark labyrinth of the Old Brewery (albeit in the company of a well-compensated constable), tripping over the inert, inebriated bodies, peeking into miserable closets housing filthy mothers and cankerous children. He’d witnessed the arbitrary violence of the streets, seen the lacerations and mutilations left by Points gang fights. He’d, of course, viewed many a corpse, carted out of fever nests, displayed on the slabs of the morgue, dumped into the broad pits on Randall’s Island. But this dogfight was a new phenomenon. The sporting reports in the Police Gazette could not do the spectacle justice. Words on paper isolated movement, made the convulsing and slashing charges discernible, knowable, coherent. What was occurring before him, however, bore no meaning because Padlin couldn’t really see what was happening. He saw Butts and Crib tear at one another, but it was like trying to freeze a waterfall, to make out the constituent drops in the avalanche of water. He saw Butts thrown this way and that as Crib tried to break his opponent’s grasp–but to Padlin it was just streaks of hide and gore. He saw Butts release Crib’s bloody stump of a nose, saw Butts twist about and dive for Crib’s front legs, snapping onto the right paw–but it took several minutes for Padlin to fracture the battle into momentary images. The fight was brutal, the attacks quick and surprising, and he grew exhausted in his vain efforts to just observe. The dogs tumbled on their sides and Crib broke free. He dove back onto Butts, catching the back of the brindled dog’s head. Butts shook and jiggered, arched his back, tried to loosen Crib, the fine hair of his skull blushing gruesomely. Crib threw his head back, yanking Butts up. He whipped his head down. Butts hit the ground hard, his legs splaying like the splatter of an overturned pie. But Crib had lost his grip. Butts twisted his trunk around, swiveled onto his back, front paws revolving, back legs churning in the air. Crib leapt toward his exposed throat. The crowd bellowed, prepared for, anticipating, the blood. Incredibly, Padlin felt a sound coming from his lips, not a yell, not a scream exactly. Something searing and anguished. The dogs were struggling, plowing the dirt, and Padlin saw Butts’s head buried in Crib’s forechest. He had a terrible hold, his teeth clamped low on Crib’s front, just above his legs. The crowd pressed down around Padlin, roaring at the pit with renewed fervor. Padlin was shouting, too. Crib jerked about, snapped his jaws just short of Butts’s burrowing head. Butts suddenly let go and, just as quickly, leapt and bit down on the stub of Crib’s left ear. He flicked his head and slammed Crib into the dirt. Padlin heard his voice yelling encouragement, yelling for Butts. The brindled dog gave Crib no time to recover. His head snapped, thrusting Crib onto the pit floor again. Padlin felt his throat grow raw, shouting for Jakesy. Butts released Crib’s head. He flew on top of his opponent. His jaws closed on Crib’s left front leg. He had it lodged in the back of his mouth, clamped between his broad molars, stretching his mouth into a foamy leer. Butts ground down, his jaw muscles bulged. Padlin heard the bone crack, and he shouted. His throat hurt with the tearing words. Padlin shouted, the name tumbling from his mouth through the din: “Mollie Maloney!” What remained of Butts’s ears twitched. His jaws shuddered open. His head whipped around. The words choked in Padlin’s throat, but Butts had spotted him. Two eyes, glinting sky-blue in the gaslight. Blood and mucous dripped from his mouth, yet his brutish face had gone slack–no, not slack: it was subtler, more horrifyingly human: startled. And, in that moment, as man and dog exchanged stares, Crib rose up from beneath his tormentor, and his teeth sank into the side of Butts’s head. Crib’s momentum threw Butts backward, his head thudding against the ground. The brindled dog was helpless, on his back, feet clawing in the air. Crib drove his opponent into the dirt, scraping him along the pit floor. The betting was fierce around Padlin, voices howling new odds. Padlin watched Crib fling the helpless Butts head over heels. The flesh tore in his clenched teeth, flapped away from his deadly grasp. Crib bore down, his fangs sinking deeper into the tissue and muscle. “Are you mad?” Waddley’s face pressed up against the side of Padlin’s head. Sweat covered his forehead. His spectacles were smeared, the frames digging into the soft skin of his cheeks. The lovers rejoined: Frank Leslie’s Orpheus and Eurydice reunited in hell. Kit Burns crawled along the inner circumference of his semicircle in the pit, desperately motioning, hollering at his felled champion. The dirt was turning to syrup around the dogs’ tethered heads. The bloody skulls thrashed in a terrible unison, Butts’s muzzle gaping helplessly up at the gaslights, Crib grinding downward. Crib’s back legs plowed, his right front paw slapping on the ground with each thrust. His maimed left leg flapped over Butts’s panting chest. Padlin saw the useless limb graze Butts’s nose. He saw Butts’s body stiffen. He saw Butts’s head lurch and his teeth mesh over the leg. Crib’s yodeling scream coursed through the room. Butts scrambled up and struck again, mercifully cutting short Crib’s cries. Butts had Crib by the ear now, pounding his head in the dirt. Bets and odds catapulted over the pit. Butts couldn’t maintain his hold, Crib’s earlier assault had seen to that. He was fighting with half of his mouth, gnawing shallowly at Crib’s ear. Crib wrenched free. Butts went for the mangled ear stub again. Crib ducked and, as Butts vaulted into him, he caught hold of the brindled dog’s throat. It wasn’t a deep bite. But Crib had a secure hold on the loose hide and, braced on his three good legs, he threw Butts. Butts managed to scurry up and Crib threw him again. Once more, Butts gained his footing and, once more, Crib sent him sprawling, his jaws still clamped on the flabby skin at Butts’s throat. They froze in place: Butts on his side, speared into the dirt by Crib’s muzzle. Burns and the sailor called and gesticulated from their semicircles. The betting numbers pulsed and spat around Padlin. Blood flecked Butts’s rising and falling ribs. Crib seemed to nuzzle into the folds at Butts’s throat, judging, considering the short trip to the jugular throbbing against his nose. He held his destroyed leg off the ground, well away from his opponent’s mouth. Padlin felt the sound beginning to rise from his throat. He felt the impulse to shout. His lips began to form the words. “Keep quiet, you fool!” Waddley gripped Padlin’s upper arm, his pudgy fingers clawing at the fabric. But another voice had risen within the pit. It was commanding, irritated, yet inchoate. Wordlessly, it demanded obedience. “Devil dog!” The sailor was shaking his fist at Burns. He called to Crib, waved his hands, trying to divert his dog’s attention. His head pressed against the dirt, only Butts’s mouth showed animation. His jaws opened and closed methodically, modulating the sound into a recognizable chant: Erro! Padlin couldn’t see Crib’s face, but his stance seemed to lose precision. Erro! Erro! A precise sound, it gained coherence and Padlin realized he was not hearing a whine or a howl or a growl but a phrase. Let go! Let go! LET GO! Crib released Butts. He gazed down at him, bewildered. He looked around at the frenzied crowd surrounding him. He turned back to Butts, still prone, now silent. “Attack!” the sailor screamed. “Kill him, you son of a bitch!” Butts struck. Crib jolted back, but Butts caught him under the jaw. Crib backed up, pulling Butts to his feet. Now the brindled dog was in control, his four legs to Crib’s three, his mouth encasing Crib’s throat like a constricting collar. Now the crowd got what it came for. The blood cascaded down Crib’s breast. Butts worked his jaws, deepening and widening the wound, aided by Crib’s jerks and jumps. They lurched together across the pit to the atonal music of the surrounding chorus, Crib’s muzzle propped on Butts’s probing skull. Butts began to whip his head from side to side. Crib’s resistance ebbed, his legs gave out. Butts picked up speed. As Crib flew to one side, Butts’s jaws sprang open and Crib toppled to the pit wall. Stamping, applauding, whistling, yelling, the men demanded their due. Winners or losers, they hungered now for a glorious, fatal finish–a magnificent kill was imminent! But Mollie Maloney’s dog merely shook his head and sashayed his rear, dirt sprinkling from his hide. He yawned, and calmly watched Crib gain his footing. Blood coated Crib’s throat and breast. From across the pit, Padlin studied his clown face, now slack, now painted in darkening hues of red, the bloated tongue lolling over his incisors. Ignoring the imprecations of the crowd, Butts ambled toward the teetering dog. Crib tensed. He awkwardly swiveled to the side of the pit and leapt. His jaw banged against the edge of the wall, and he fell back. Before he hit the ground, Butts was on top of him. Clinging to Crib’s throat, Butts shook the life out of him. The sailor fell onto his stomach and, stretching out his arms, vigorously fanned his failing dog. Crib’s head flopped from right to left, drool looping around him like a crimson lariat. Kit Burns rose in his semicircle. He flicked the back brim of his top hat, knocking it jauntily over his brow. He nodded to his baggy-clothed assistant positioned along the pit wall. The boy nodded back and shouted: “Game!”

Chapter X As soon as he had some elbowroom, Waddley pulled his tattered pad from the relative protection of his armpit and propped it against the pit wall. Despite his trepidation, betrayed by occasional furtive glances to the right and left, Waddley was the quintessence of efficiency. He quickly defined Butts astride Crib’s corpse, merely suggesting the terrain of the fighting pit and the surrounding bleachers (now quickly emptying) before he impetuously turned to another page.

Padlin slouched beside Waddley, arms dangling between his knees. The portly youth’s energetic pencil work was barely tolerable to him. Padlin was completely spent and yet the fight was still churning through him, making all the images and activity about him too brilliant, too vibrant–like an overvarnished canvas. Abruptly, Waddley dropped his pencil and slammed his pad down against the upright planks. “Damn you, Padlin! Why don’t you draw?” Padlin was too overwhelmed and too tired to respond. Waddley angrily turned back to the pad and made a few vicious swipes with his pencil. He stopped, staring at the paper. He let out a long breath. “All right, Padlin.” Waddley flipped the pad closed, laid it on his lap and awkwardly crossed his short legs. “Let’s be frank with one another.” He placed his hands on the pad, entwining his fingers. “What are you scheming?” Waddley looked up, searching for Padlin’s eyes. “For God’s sake,” he suddenly snapped, “take off that damned hat!” Padlin didn’t move or speak “I admit, I underestimated you,” Waddley continued. “I admit, sir”–the last said with an emphasis that pronounced disingenuousness–“that I find your tactics unfathomable.” Waddley set his pad on the bench between them. With a grunt, he twisted to better confront his colleague. He briefly gazed over Padlin’s shoulder, his lips forming silent words, his hands bobbing in the air, the entwined fingers pressing tighter. Padlin watched the flesh bulge around the ring that adorned Waddley’s left hand. Waddley nodded in recognition of some resolution: “Am I not correct in believing, Padlin, that you were prepared to kill me this morning?” He waited a moment, his expression quickly sinking in tandem with his expectation of an answer. “Yes,” he finally said, Padlin’s surrogate. “And, am I not also correct in believing that your attempt on my person was your own peculiar way of achieving this assignment?” Again, a pause before Waddley accepted defeat. “Yes,” he exhaled. His clasped hands began to jitter up and down. “Then, please, explain this to me. Explain to me why you conceded the contest even as we entered this wretched place. Explain why you won’t even try to set your meager hand to paper.” Waddley’s clasped hands thumped the bench. “All right. Then tell me this.” He squirmed, cocking his head in a manner that was meant to suggest intimacy but only reminded Padlin of the late Crib. “Tell me what possessed you to bellow during the fight?” Another moment passed before Waddley, still speaking as if on Padlin’s behalf, said, “Yes.” His expression suddenly dilated, like the victim of an electric shock. His spectacles slid forward on his sweat-slick nose. “Now I see it,” he stammered. He fearfully peered up at Padlin, the apex of his still-clasped hands shaving his nose. “You didn’t shout to bring calamity down upon yourself,” Waddley whispered. “It was to bring calamity down upon me.” Padlin looked at Waddley, amazed at the infantile terror palsying his features. “You don’t understand,” Padlin finally said, shaking his head. “You can’t understand.” Padlin glanced toward the pit. “I thought I understood. But I don’t–” Butts stood in the dirt below, no more than four feet away, his mauled face turned up toward the two Special Artists. His muzzle was swollen, one side thick with clotted gore. His brindled hide had lost its luster, the short hair mottled by patches of dried blood. Butts’s stance, though, was steady and his eyes alert. Those eyes, Padlin thought, what had Mollie Maloney said about them? Padlin couldn’t remember, but their concentration was remarkable. Disconcerting. Padlin tentatively leaned forward. Maybe it was the effect of their color. The eyes were flawlessly blue; looking into the pupils was like gazing into depthless sky. Butts’s clipped ears twitched, his eyes narrowed and his flews curled into a snarl. The wounded skin crackled as the fangs and black gums appeared. A long growl rose from his throat, a clearly pronounced rolling “r.” A tumbling, menacing canine letter. Waddley scuttled back on his seat. Padlin remained crouched over the pit wall. He carefully raised his hands. “Jakesy,” Padlin said. The dog blinked. The ear stubs shivered. “Jakesy.” The growl died. The dog’s expression faltered. The change was eerie, its flexibility too extreme. The dog grimaced harshly, a cringe that did not suggest primitive fear as much as painful recollection. Padlin’s stomach scraped against the pit wall. “Jakesy,” he said, “I knew Mollie.” The eyes fluttered open. Padlin now remembered what Mollie Maloney had said about the eyes, how they conveyed a tortured life and a terrible knowledge of mankind. But she had been wrong. The eyes did not alone transmit such . . . such consciousness: it was his whole countenance doing that, the workings of the tiny muscles and nerves rendering a contorted map of character and conscience. What Padlin saw was a being trapped in a living hell.

Go to The Hungry Eye, Episode 2

Go to The Hungry Eye, Episode 4

This article originally appeared in issue 2.2 (January, 2002).