Baltimore | Boston | Charleston | Chicago | Havana

| Lima | Los Angeles | Mexico City | New Amsterdam | New Orleans

Paramaribo | Philadelphia | Potosi | Quebec City | Salt Lake City

Saint Louis | Santa Fe | San Francisco | Washington, D.C.

About 1710, J. D. Herlein, a Dutch visitor to Paramaribo, reported that a runaway slave from the town had been recaptured by the authorities. His sentence, which the court intended “to serve as an example to others,” was “to be quartered alive, and the pieces thrown in the River.”

Herlein witnessed the execution: “He was lain on the ground, his head on a long beam. The first blow he was given, on the abdomen, burst his bladder open, yet he uttered not the least sound; the second blow with the axe he tried to deflect with his hand, but it gashed the hand and upper belly, again without his uttering a sound. The slave men and women laughed at this, saying to one another, ‘That is a man!’ Finally, the third blow, on the chest, killed him. His head was cut off and the body cut in four pieces and dumped in the river.” Herlein made clear that the harshness of this sentence was no anomaly, explaining to his European audience that “if a slave runs away into the forest to evade work for a few weeks, upon his being captured his Achilles tendon is removed for the first offence, while for the second offence, if they wish to increase the punishment, his right leg is amputated in order to stop him from running away; I myself was a witness to slaves being punished thus.”

As in other capitals of New World plantation colonies, maintaining order among the mass of enslaved laborers was a central concern. In the idealized slaveocracy, planter hegemony would leave little room for slave response or maneuver and dramatic public executions, a veritable theatre of terror, played a central role toward this end. But the victims in the colonies, unlike those who suffered judicial penalties in the metropoles, generally refused to play their designated roles and mocked the system until their dying breaths, flaunting their individuality and resistance.

In the exercise of totalizing power, capital punishment constitutes a limiting case–yet for this very reason, it may be a good place to plumb the ultimate capacities of the oppressed to respond, resist, and create. An examination of the ways that condemned slaves went to their deaths reveals much about the limits of planter power and about the spirit that allowed slaves to create, within the limited spaces available to them, a world of their own, one that influenced not only every aspect of their own descendants’ lives but also that of the descendants of their oppressors.

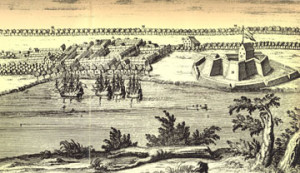

By the time of Herlein’s visit, Paramaribo was a small, bustling town that served as the administrative and commercial hub of a fast-growing sugar plantation colony in northeastern South America. Named after the Amerindian village that had occupied the site, ten kilometers up the Suriname River from the Atlantic, it was dominated by the wooden fort (Zeelandia) that gave the town its name in the creole language created by the slaves: Foto. The first fort, and the town itself, were founded soon after 1650, when Frances Lord Willoughby of Parham sent out an expedition from Barbados to establish the English colony that lasted until the Treaty of Breda (1667), in which the English traded Suriname for New York with the Dutch.

The town had grown from fewer than thirty houses in 1678–the homes of officials, inns, and public houses–to a couple of hundred structures with some five hundred people, only 3 percent of the colony’s population but one-third of its Europeans (who included Dutch, French, Portuguese, Jews, Germans, Scandinavians, and others). The remaining whites lived either in and around the town of Jews Savanna fifty kilometers upstream, which had its own synagogue and where half the colony’s slaves were owned, or on the plantations themselves. Paramaribo was the port where planters and their delegates did their shopping for slaves as well as other goods, all of which moved between town and plantations in boats rowed by slaves, and where they carried out their administrative affairs. In the early eighteenth century, over 95 percent of the colony’s eighteen thousand slaves–almost all of whom had been born in Africa and two-thirds of whom had arrived during the previous decade–worked and lived on plantations.

By 1710, neither Paramaribo nor the colony had reached the heights of wealth and depravity they were to achieve in the second half of the eighteenth-century, when, as John Gabriel Stedman described, planters were routinely served at table by nearly nude house slaves, who also fanned them during their naps (and sometimes all night long), put on and took off all of their clothes each morning and evening, bathed their children in imported wine, and performed other similar tasks, and when wealthy planters in Paramaribo often had forty or fifty such handpicked domestic slaves. Nevertheless, even by 1710, the local plantocracy was, to borrow Gordon K. Lewis’s phrase about the Caribbean more generally, “crassly materialist and spiritually empty . . . the most crudely philistine of all dominant classes in the history of Western slavery.” And Stedman’s description of the town would already hold as well: “Paramaribo is a verry lively place, the Streets being crowded with Planters, Sailors, Soldiers, Jews, Indians, and Negroes, while the river Swarms with Canoes, barges, yoals, Ships boats &c constantly going and coming from the different Estates and crossing and passing each other like the wheries on the Thames . . . while continually some Guns are firing in the roads from the Shipping, and whole Groops of naked Girls are playing in the water like so many mermaids, can not but have a truly enchanting appearance from the beach, and in some Measure Compensates for the many Curses that one is here dayly exposed to.” As would his recounting of a Paramaribo experience that could have happened as easily at the beginning of the century as later: “A general hub bub took place [and] . . . A Mob now gathered and a riot ensued, before Mr. Hardegens Tavern at the Waterside while hats wigs[,] bottles and Glasses flew out at his Window[.] [T]he Magistrates were next sent for to no purpose and the fighting continued in the Street till 10 OClock at night, when I with my friends fairly keep’d the field, having knocked down several Sailors, planters, Jews, and Overseers and lost one of my Pistoles which I threw after the rabble in my Passion . . . after which we all sat down and drank away the night till the Sun rose the next morning.”

Paramaribo in 1710, like the rest of Suriname, was divided by race, and hence status. Whites were free, blacks were slaves. Yet there was constant interaction. Interracial sex–white men with slave or Amerindian women–was an everyday occurrence (though laws were passed against it, the penalty was a fine of a mere two pounds of sugar), and during Herlein’s visit there even were two scandals involving white women and slave men, prompting the governor to issue an edict stipulating flogging and expulsion from the colony for a woman if she was single, with branding added if she was married, and with the African man to be executed in either case. Edicts were repeatedly issued to keep whites and blacks apart (suggesting that everyday practice often trumped the law)–and also to preserve status differences: in 1698, it was decreed that “all slaves, both male and female, will be obliged to stand aside and make way for any European who may cross their path, day or night,” and further that Europeans and slaves were not permitted to gamble together, nor could slaves carry sticks or cudgels. With a ratio of whites to blacks of one to twenty overall, and one to forty in the plantation districts, the master class lived with ever present fear of slave rebellion. The plantocracy, who controlled the judiciary, had since the founding of the colony mandated the cruelest punishments for resistance.

Theatrical public executions were reported during the earliest years of settlement–always accompanied by wonderment at the stoicism and resistance manifested by the African victims. In the initial English period (1650-67), George Warren observed of runaways that “[i]f the hope of Pardon bring them again alive into their Masters power, they’l manifest their fortitude, or rather obstinancy in suffering the most exquisite tortures can be inflicted upon them, for a terrour and example to others without shrinking.” And the indomitable Aphra Behn–another visitor to the English colony–wrote her fictional account of the death of the slave-prince Oroonoko: “He [Oroonoko-Caesar] had learned to take Tobacco; and when he was assur’d he should die, he desir’d they would give him a Pipe in his Mouth, ready lighted; which they did: And the Executioner came, and first cut off his Members, and threw them into the Fire; after that, with an ill-favour’d Knife, they cut off his Ears and his Nose, and burned them; he still smoak’d on, as if nothing had touched him; then they hack’d off one of his Arms, and still he bore up, and held his Pipe; but at the cutting off the other Arm, his head sunk, and his Pipe dropt, and he gave up the Ghost, without a Groan, or a Reproach . . . They cut Caesar [Oroonoko] into Quarters, and sent them to several of the chief Plantations.”

During Herlein’s visit, some of the enslaved African ancestors of today’s Langu clan of Saramaka Maroons managed to make their escape from Paramaribo, where they had been working under military surveillance on the outskirts of the city. As Saramakas recounted it in the late twentieth century, “The whites had moved the slaves to a new barracks called Lúósu, a great long house right where the gas company is today. In those days, the whole city was right around the governor’s house . . . At Lúósu our ancestors used to sleep on banana leaves. That was our hammock! . . . There they decided to escape.” A large expedition–forty-eight slaves, sixty-two Amerindians, and seventeen whites–was sent after these runaways, based on intelligence from two recaptured runaways, Bassot and Diamant, who were later burned at the stake “as an example to others,” but the Maroons had been warned by their scouts and escaped further into the forest. (By this date, something like two thousand slaves had already become successful Maroons, living in organized groups, farming together, and conducting their lives under wartime discipline.) A few years later, two large military expeditions captured a number of Maroon villagers, and the criminal court in Paramaribo meted out the following sentences: “The Negro Joosie shall be hanged from the gibbet by an Iron Hook through his ribs, until dead; his head shall then be severed and displayed on a stake by the riverbank, remaining to be picked over by birds of prey. As for the Negroes Wierrie and Manbote, they shall be bound to a stake and roasted alive over a slow fire, while being tortured with glowing Tongs. The Negro girls, Lucretia, Ambira, Aga, Gomba, Marie, and Victoria will be tied to a Cross, to be broken alive, and then their heads severed, to be exposed by the riverbank on stakes. The Negro girls Diana and Christina shall be beheaded with an axe, and their heads exposed on poles by the riverbank.”

In 1750, the slaves of a planter named Amand Thomas murdered him and his bookkeeper but were soon recaptured in the forest. Governor Mauricius described how “[t]he execution of Thomas’ slaves took place in the afternoon; three, including Gallien, who murdered the bookkeeper, and a Negro of Thumelaar’s, have been hanged by suspending them from an iron hook twisted through their sides; three, including one of Lespinasse’s, have been broken on the wheel; two have been burnt at the stake, two hanged and twenty quartered, two of whom were beheaded.”

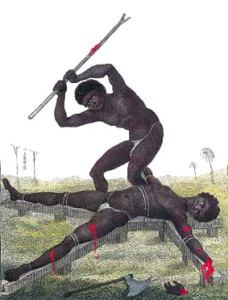

By far the best-known account of a Paramaribo execution dates from 1776–John Gabriel Stedman’s dramatic description of the torture of Neptune and his breaking on the rack, illustrated for all time on the basis of Stedman’s drawing by William Blake.

As Stedman wrote, Neptune was “a Carpenter by Trade, he was Young and handsome–But . . . he having Stole a Sheep to Entertain some Favourite Women, the Overseer had Determined to See him Hang’d, Which to Prevent he Shot him dead Amongst the Sugar Canes–this man being Sentenced to be brook Alive upon the Rack, without the benefit of the Coup de Grace, or mercy Stroke, laid himself down Deliberately on his Back upon a Strong Cross, on which with Arms & Legs Expanded he was Fastned by Ropes–The Executioner / also a Black / having now with a Hatchet Chop’d off his Left hand, next took up a heavy Iron Crow or Bar, with Which Blow After Blow he Broke to Shivers every Bone in his Body till the Splinters Blood and Marrow Flew About the Field, but the Prisoner never Uttered a Groan, or a Sigh.”

In 1710 Paramaribo was the capital of a plantation colony firmly set in the American space of death (which was also of course a space of enormous cultural creation). In this particular space, within the totalizing world of the plantation system, theatrical public executions constituted central rituals of colonial control. But from Oroonoko to Neptune, it is the spirit of those whom the planters tried to crush that continues to inspire, that continues to give hope.

Further Reading:

J. D. Herlein’s remarks can be found in his Beschryvinge van de Volk-plantinge Zuriname (Leeuwarden, 1718), 112, 117; John Gabriel Stedman’s in his Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, transcribed from the original 1790 manuscript, edited, and with an introduction and notes, by Richard and Sally Price (Baltimore, 1988), 181-82, 236; Neptune’s execution is discussed in that same text, 546-50; George Warren’s quotation may be found in his An impartial description of Surinam (London, 1667), 19; Aphra Behn’s in her Oroonoko or The Royal Slave: A True History (London, 1688). Saramaka accounts of their early history, and reports of the expeditions against them, can be found in Richard Price, First-Time: The Historical Vision of an Afro-American People, 2d edition (Chicago, 2002); Governor Mauricius is quoted in R. A. J. van Lier, Frontier Society (The Hague, 1971), 139. For an extended argument about public executions and slave resistance, see Richard Price, “Dialogical Encounters in a Space of Death,” in John Smolenski, ed., New World Orders: Violence, Sanction, and Authority in the Early Modern Americas, c. 1500-1825 (Philadelphia, in press).

This article originally appeared in issue 3.4 (July, 2003).

Richard Price, who divides his time between Martinique and the College of William and Mary, has recently published The Convict and the Colonel (Boston, 1998) and, with Sally Price, Les Marrons (Châteauneuf-le-Rouge, 2003) and The Root of Roots: Or, How Afro-American Anthropology Got Its Start (Chicago, 2003). Further information on his publications can be found at www.richandsally.net.