While studying the mail habits of nineteenth-century Americans, I became a sounding board of sorts for a familiar refrain in current discussions of modern life: that e-mail is burying the personal letter. Sympathetic strangers, at an initial loss to make sense of my interest in the postal service of yesteryear, would venture the guess that I was nobly seeking to retrieve some recently lost art of correspondence. Isn’t it a shame, I kept hearing, that no one writes letters anymore. Some members of this chorus dramatized the tragedy in archival terms, speculating that the kind of research I was conducting will be unavailable to historians studying our own era, since computer-bound Americans at the dawn of the twenty-first century no longer generate the holographic documents that comprise manuscript collections in libraries and historical societies.

But as often as the case against e-mail was presented, it never ceased to surprise me. For starters, nothing in my own experience suggests that electronic mail is replacing handwritten personal correspondence. It has been several decades since large numbers of Americans used the U.S. mail for the majority of their long-distance communications or for casual daily contact with nearby friends and family. Telephones were introduced in the United States over one hundred and thirty years ago, only a generation after postage reform made regular mail use affordable for a majority of Americans. As service became more common and more affordable, the phone began to compete in important and interesting ways with the culture of the post.

By the time of my own childhood in the 1970s, habitual dependence on letter writing for forging and maintaining relationships across distances was increasingly uncommon, the distinctive province of marginal groups notable in part for their impeded access to phones—the poor, prison inmates, kids at summer camp. Only a negligible proportion of the electronic messages I have sent and received over the past fifteen years would have been inscribed on paper and mailed during the previous fifteen-year period. Many of them, it seems clear to me, would have passed electronically (and ephemerally) over telephone wires. A smaller but significant fraction might have been communicated face-to-face or through broadcast advertising (radio, television, print, or outdoor). The vast majority would undoubtedly have gone uncommunicated. A future historian wishing to study the lives of people like me will thus have far more material to work with after 1990 than before. Moreover, the life that such a historian would be studying is a life significantly shaped by daily acts of writing, receiving, and expecting mail. If e-mail has indeed changed our habits of communication, it has always appeared to me, we should interpret the shift as a revival of epistolarity rather than its death knell. And of course part of my motivation for writing a book on postal culture in the nineteenth century lay in the expectation that I would discover an analogous historical moment to the one I now inhabit.

From the early days of widespread computer-mediated correspondence, commentators have debated the textual status of e-mail and its place in the history of communications technology and media. Typed messages conveyed through e-mail accounts, cellular phones, or networking Websites both resemble and differ from the contents of older postal systems. For starters, these new media typically (though not in the case of instant messaging) store and forward their messages much like snail mail, though at a different pace, of course. And in profoundly transformative ways, computer-mediated correspondence tends to implicate both the sender and the recipient in other networks and media of information exchange (such as the Internet) that unsettle the boundaries of the message itself. But whether one is more interested in the way e-mail has dematerialized, accelerated, and deformed the traditional letter or more impressed (as I am) by the way it has textualized interactions that used to be conducted orally and has staggered interactions that used to take place simultaneously, the relationship between old and new mail cannot be reduced to such structural, technological criteria. A British sociolinguist recently proclaimed e-mail “the first major upheaval in written English since the invention of the printing press,” but e-mail is not itself a writing system that might constitute such an upheaval nor is it an innovation in inscription or reproduction that warrants a comparison to printing. Assessing the cultural significance of a massive popular shift to electronic message sending requires tabling conventional schemas of orality and literacy, writing and print. Nothing about the technology of e-mail predetermines even whether we employ it synchronously or asynchronously, to broadcast to mass audiences or to conduct personal interactions. The meaning of e-mail depends on how we use new media and how we talk about them.

It may still be early to discuss the place of e-mail in the history of American culture, but the recent publication of Send: The Essential Guide to Email for Office and Home (New York, 2007) probably signals a starting point. Written by two young, successful figures working at the center of contemporary print culture (David Shipley edits the op-ed page of The New York Times; Will Schwalbe was, until very recently, editor in chief at a major New York publishing house), Sendhas spent time on the bestseller lists and enjoyed lavish critical praise in prominent cultural venues. In part a practical guide to the technical workings of the system, in part a self-help manual for avoiding electronic miscommunication (especially at the workplace), and in part an entertaining analysis of the social implications of e-mail, Send has been welcomed by reviewers as the book they’ve long needed. Elegant and readable, Shipley and Schwalbe’s book has succeeded in large measure because it speaks effectively to a range of readers and e-mail users. But even a less skillfully conceived project would interest current readers—and future historians—insofar as it captures (and documents) our awkward social adjustment to the ubiquity of new communications practices.

Send is very much a book of its moment, but those who have read epistolary manuals from earlier eras will find themselves on generally familiar ground. Popular guides to writing letters, an established genre in Europe and North America by the eighteenth century, flourished in the United States in the antebellum era, offering readers some sort of guidance to a mode of communication that was becoming increasingly indispensable for ordinary people. That readers purchased or used these guides for practical help with composition seems doubtful, especially given how many nineteenth-century “American Letter Writers” entertained their readers with lengthy examples of recycled correspondence between wise adults and impetuous youths. Presumably, an admonishing letter by an uncle to his spendthrift nephew and the exchange between a parent and a child over spouse selection—both letters straight from the pen of the eighteenth-century novelist Samuel Richardson—were valued as entertainment or moral instruction. Even those texts that presented more original letter samples than the typical Richardsonian rehash catered to the same concerns and appetites. One 1830 text included a correspondence between Thomas Tradelove and Charlotte Easy as well as a series of exercises, one of which asked its young readers to “write to your uncle, that since the death of your father, you had been frequently engaged in considering on what profession it would be most adviseable for you to follow so as to be most useful to the world. Tell him that your heart was most bent on the study of divinity, and pray that as soon as you may be found properly qualified, you may be sent to some theological seminary.”

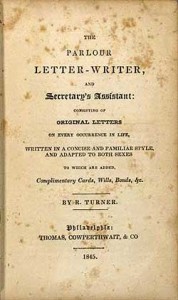

Elsewhere, entries entitled “Letter from a Gentleman to a Lady, disclosing his Passion” or “From a young Lady to a Gentleman, complaining of Indifference” (in both cases followed by a reply) blur the lines between letter-writing guides and epistolary fiction, while the claims of some guides that their rivals “mislead the rising generation, and pervert their taste, [causing] serious evil” mark the overlap with other kinds of conduct literature. Yet despite these fuzzy borders, titles such as The Fashionable Letter Writer; Or, Art of Polite Correspondence (numerous early nineteenth-century editions); The New Universal Letter-Writer; or, Complete Art of Polite Correspondence (1854); The Parlour Letter-Writer, and Secretary’s Assistant (1845); The Ladies’ and Gentlemens’ [sic] Letter-writer, and Guide to Polite Behavior, containing also, moral and instructive aphorisms for daily use (1859); Martine’s Sensible Letter-Writer (1866); Carrie Carlton’s popular letter-writer: A valuable assistant to those engaged in epistolary correspondence, and peculiarly adapted to the requirements of California (1868) formed a clearly identifiable genre of popular literature.

Pervasive anxiety among nineteenth-century letter-writing guides concerning the conduct of young people was telling. Discussions of epistolary and postal practices in periods of expanding postal service often dramatized scenes of secrecy and surveillance within family life, while inevitably raising the concerns about sincerity and influence that lay at the heart of the larger project of conduct literature. Letter-writing guides weren’t composition how-to books; they were maps and manuals for social relations.

Like those predecessors, a twenty-first century book on e-mail etiquette is at core a guide to etiquette more generally. Much of the advice in Send on what not to do in electronic correspondence stresses reciprocity, courtesy, and consideration, extending familiar applications of the Golden Rule to the electronic frontier. And much of the advice for navigating the everyday epistolary demands of the workplace applies more broadly to other kinds of writing. “Email has vastly increased the amount of writing expected of us all,” the authors observe, “including people whose jobs never used to require writing skills.” Not surprisingly, then, an “essential guide to email” turns out to be the place for supplying proper definitions for commonly misused words or discussing grammar. E-mail is, after all, where many of us produce most of our prose (and our poetry too).

But the timely appeal of a book like Send lies less in its sensible reminders to behave considerately, to proofread, and to strike the right balance between polite and friendly salutations. What the book really offers is a window into a set of habits that are partially invisible to us in everyday life. E-mail is one of those interesting practices that straddle the border between public and private conduct. Exchanging e-mail is never, by definition, a solitary activity (however often we compose and read in solitude), but it frequently invokes or produces an experience of intimacy between correspondents. We know that countless others are exchanging electronic messages, and we may imagine them to be similar to our own, but we rarely get to see those messages. And yet unlike many other modes of interpersonal contact, e-mail seems particularly vulnerable to spilling over the walls of one-to-one intimacy and into public view. The ease with which messages can be archived and inspected by others, instantaneously broadcast to multiple readers, misdirected to unintended recipients, or forwarded virally over time to a mass audience powerfully shapes the experience and meaning of e-mail.

Shipley and Schwalbe offer readers numerous opportunities to admire the handiwork or (more often) to laugh at the awkward mistakes of other private users of the medium. And they underscore the potentially unsettling publicity of e-mail by exposing numerous examples of a particular brand of faux pas: the publicity agent who inadvertently alienates a newspaper editor when he forgets to edit the “cc” line on a letter to his client; a contract salesman who lost his job when a Justice Department investigation uncovered a potentially incriminating note to his competitors; a corporate executive forced to resign after an outrageously imperious note to a subordinate gets circulated throughout the company and in the press; or a London lawyer who becomes an object of public ridicule when he repeatedly and shamelessly duns a secretary to pay for spilling ketchup on his trousers. Narrating all of these cases in the pages of a bestselling book doubly dramatizes the susceptibility of e-mails to unwanted circulation, providing voyeuristic satisfaction as it conveys a friendly warning. We are drawn to reading e-mails that were composed by strangers and not intended for our eyes, even (or maybe especially) when they are painful to look at. And the reminder that e-mail easily eludes the control of its senders speaks directly to a profound sense of what might be new about this medium.

But even here, parallels with snail mail in nineteenth-century America bubble to the surface. Purportedly intimate letters frequently found their way into court records, newspapers, and books, not always with the consent of their authors. (During the scandalous Beecher-Tilton affair, when the prominent minister of one of the wealthiest churches in America was accused of adultery, letters between Elizabeth and Theodore Tilton published in the Chicago Tribune became something of a literary sensation.) Ordinary users of the post frequently worried about who would read their letters and routinely asked the addressee to “burn this letter.” An etiquette guide from the 1850s advised young women to avoid corresponding with men they did not know well, lest the intended recipient show the letters to his friends for unflattering effect. The same guide also described a class of women who entice men into correspondence and then profit “by selling the letters for publication.” As practices of daily communication shifted from conversation to written correspondence, new postal users contemplated the pleasures and dangers of concealment and exposure that seemed to come with the new territory. Our electronic missives certainly leave different sorts of unintended traces in everyday life and on the historical record than the paper letters currently living in drawers, attics, and archives, but are we certain that the anxieties and discussions they provoke are novel?

Further Reading:

Simeon J. Yates, “Computer-Mediated Communication: The Future of the Letter,” in David Barton and Nigel Hall, eds., Letter Writing as Social Practice (Philadelphia and Amsterdam, 2000); Lisa Gitelman, Always Already New: Media, History, and the Data of Culture (Cambridge, Mass., 2006); Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge, Mass., 1999); Paul Starr, The Creation of the Media: Political Origins of Modern Communications (New York, 2004): William Merrill Decker, Epistolary Practices: Letter Writing in America Before Telecommunication (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1998); Roger Chartier, Alain Boureau, and Cécile Dauphin, Correspondence: Models of Letter-Writing from the Middle Ages to the Nineteenth Century, trans. Christopher Woodall (Princeton, 1997); Katherine Gee Hornbeak, “The Complete Letter-Writer in English 1568-1800,” Smith College Studies in Modern Languages XV (1934).

This article originally appeared in issue 8.3 (April, 2008).

David Henkin lives in San Francisco, teaches in Berkeley, maintains family relationships in New York, and spends way too much time engaged in electronic correspondence. His most recent book, The Postal Age: The Emergence of Modern Communications in Nineteenth-Century America (2006), probably reflects all of those circumstances.

!["The Pocket Letter Writer." Color added title page from The Ladies' and Gentlemens' Letter-Writer and Guide to Polite Behaviour (Boston, [ca. 1860]). Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.](http://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/8.3.Henkin.1-182x300.jpg)

![Title page from The Ladies' and Gentlemens' Letter-Writer and Guide to Polite Behaviour (Boston, [ca. 1860]). Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.](http://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/8.3.Henkin.2-186x300.jpg)