The Royal children have been sent a gift—

A map of Europe from 1766

Complete with longitude, painted onto wood,

Like any other map in brown and green and red,

But then disfigured: cut up into parts,

A disassembly of tiny courts

Strewn across the table. There is a key

To help the children slot, country by country,

The known traversable world in place:

Little Tartary, Swedish Lapland, France,

The Government of Archangel. The sea

Has been divided into squares, crudely,

As though the cast-iron sides of nations

Still applied (but with more attention

To geometry) while the engraver’s signature

—A circle, his name, a folded flower—

Has been deftly sawn in half. If successful,

The three young princes and the oldest girl

(This is not, after all, a lesson in diplomacy

So she can play too) will, ironically,

Undo the puzzle’s title and its claim:

Europe Divided in its Kingdoms

Shall be Europe reconfigured, whole.

They start in the top left corner with the scale

Then fill the other corners in: ‘Part of Africa’,

A scroll, the blank of simply ‘Asia’

Rolling off to hordes and steppes and snow

Beyond the boundary. Outlines follow,

Aided by exquisite lettering:

‘The Frozen Ocean’ solidifies across the map’s ceiling.

And so the Royal children spend an hour

Staring and exclaiming, clicking together

(What joy!) the angled buttress of a continent—

Their own unlikely island on a slant

By its farthest edge, and in their trance ignore

What will no longer fit: Aotearoa, America.

Statement of Poetic Research

More delicate than the historians’ are the map-makers’ colours

—Elizabeth Bishop

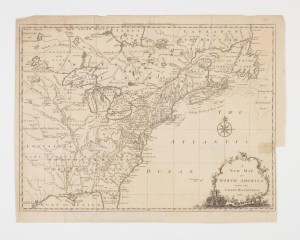

Maps are aspirational documents. Flat, two-dimensional, odd, we need to learn how to read them, like alphabets. We need to be tutored in their signs. Maps signal, loudly, the differences between their own small selves and the enormous things they claim to represent, be it mountain-range, territory, country, or empire, and into this gap rushes desire. Let no Irish be spoken in this parish, declares an early English-language map of Ireland, with its badly translated place-names, and eventually it shall be so. For maps are also weapons. They have consequences. They are conduits of power. They are so freighted with internal and external paradox they are already, all by themselves, difficult to resist as poetic subjects. And then in England, in 1766, as tensions were beginning to build toward the American Revolutionary War, John Spilsbury, wood engraver and map-maker extraordinaire, hit on a bizarre idea. He drew a map of Europe on a wooden base and then cut it up into pieces so that it could be put back together again, over and over again, as a game, and the world’s first jigsaw puzzle was born.

As America wrenched itself free of British control, Spilsbury (who drew a beautiful “New Map of North America from the Latest Discoveries” in 1761, before the outbreak of war) turned his attention east, to Continental Europe, away from British controlled territory altogether, and invented an activity for obsessives, obsessively focused on the breaking and re-making of national boundaries. His “Europe Divided into its Kingdoms etc.” is exquisite, and he signed it in the middle of the sea, where no country could claim him, before carefully dismembering it. Was this a subversive act? Was it therapeutic? Was it an act of looking at what was happening to the British Empire by looking away? Is the world’s first jigsaw puzzle an objective correlative for imperial loss?

I did two contradictory things with Spilsbury’s jigsaw as I wrote about it. First, I exaggerated the complicated power dynamics intrinsic to both maps and maps-cum-jigsaws by making the solvers of the jigsaw children of the British royal family, for whom nation-building and nation-breaking may well become actual activities, later in life, and especially in the context of a Europe set on fire, in turn, by revolutionary fervor. One of these children is a girl, throwing a whole other massive and unstable element into the mix. In my head these children piece a broken continent back together again over the course of a firelit afternoon, in an airy dayroom with a high ceiling and a polished floor, and it brings them joy.

The second thing I did was to put my—by now totally overwhelmingly meaningful—subject in a box by setting the poem out as a single block of text in rhyming couplets. Poetic form is a possible way through confusion. To paraphrase Auden, adherence to form saves us from the tyranny of what we were going to say next. But form also multiplies meaning through its own formidable articulacy; it is, in itself (and rather like a map, or a jigsaw, or worse, a jigsaw of a map) profoundly paradoxical.

I wanted my poem to click down the right hand side, like the jigsaw being clicked into place, piece by piece, and I wanted it to echo an Augustan poetic sensibility: rhyming couplets, the preferred form of Dryden and Pope, suggested both of these things. Reserve is the poem’s formal hallmark: it keeps tidying itself away as it goes. It works methodically through its line-by-line description to give us the map of Europe back whole, just as solving the jigsaw eventually does too. The rhyming couplets of the poem and its subject, the map, enact, therefore, a doubled fantasy of control over language and over territory, both of which are always threatening to rebel. Content and form not only complement each other; they also work to highlight the inherent inadequacies of both maps and couplets, for the underbelly of control is always fear, and our consolations, which are both unnatural and dishonest, fraught with further difficulties.

America is free by the poem’s end and is given, delightfully, the final word. Aotearoa is the Maori word for New Zealand and means “the land of the long white cloud,” ironically transcribed of course in the letters of the English alphabet, but a word so far outside the world-view of my royal children as to act as a radical interloper in the poem. I can only gesture briefly toward “what will no longer fit.” But “what will no longer fit” is the poem’s real subject all along: my homage to revolution and to pattern-breaking, squeezed into its Augustan box.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.2.5 (Spring, 2016).

Sinéad Morrissey has published five collections and is the recipient of numerous awards for her work, including a Lannan Literary Fellowship and the T S Eliot Prize. Her most recent collection, Parallax and Selected Poems, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2015, was a finalist in this year’s National Book Circle Critics Award for poetry.