“My Father in the New World” is a villanelle (for celebrated examples, see Dylan Thomas’s “Do Not Go Gentle Into that Good Night,” and Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art”). I’ve always found the form not only haunting but indicting. That is, each time the rhyming repeated lines (lines 1 and 3 of the first stanza) come round again in subsequent stanzas, they carry greater weight, and what might be an off-hand observation at the beginning of the poem becomes an undeniable and perhaps terrifying truth by the villanelle’s end. I’ve played with the form slightly in the last stanza here, and, likewise, instead of the designated rhyme words’ prescribed repetitions in the subsequent lines, I have replaced them (for the fun of playing with the tradition) with homonyms. Thus, instead of the first stanza’s respective fleece you and please you, I’ve altered them each time so that we get flees you/ fleas you/ felicity, yours; alternating with police you/ polishing your/ pleas you/ pole will ease you. I’ve loaded “My Father in the New World” with American clichés about diligence and industry, but end it with a reference to Charon, via the flatboat pilot who would eventually ferry all the Keatses, Fanny Brawne, Charles Brown, Audubon, my father, and, sooner or later, reader and writer, across his wide river.

Research has included two visits to Wentworth Place in Hampstead (now a London suburb) where John Keats lived for nearly two years with his friend Brown. For a while, the Brawne family shared the residence with the two young men, living in the house’s larger, partitioned-off section. I visited, too, the beautiful Keats-Shelley House where Keats died in Rome. The museum hosts paintings and memorabilia of Keats and his immediate circle, but also of Shelley, Byron, others, and of Victorians who revered Keats. I looked up at the tall, square-patterned, flower-carved ceiling that Keats stared at for much of his three months there. Immediately outside one bedroom window is the famous Spanish Steps. From the other window of the narrow six-by-fifteen-foot room overlooking the broad Piazza di Spagna, Keats dumped the awful food prepared for him and his companion, Joseph Severn, in protest. The meals, cooked in the landlady’s trattoria downstairs, improved thereafter.

The artist Joseph Severn had accompanied Keats to Rome from London, valiantly attending to Keats until the poet’s death on February 23. Severn himself spent many years in Rome and died there in 1879. He is buried next to his friend at the very lower left of the Protestant (i.e., non-Catholic) cemetery laid out behind the Roman Pyramid of Cestius. Shelley’s grave is close by, upward to the right.

Fiancée Fanny Lindon, née Brawne, (whose father and brother both died of consumption) passed away in 1865. Sister Fanny Llanos, née Keats, died in Madrid in 1889. Her future husband, Valentin Llanos, coincidentally met John in Rome three days before John died. George, ruined by the 1837 Panic, died in 1841 on Christmas Eve in his Louisville mansion, “the Englishman’s palace.”

Further Reading

I have relied here mostly on modern biographies of John Keats, starting with W. Jackson Bates’s Pulitzer Prize-winning John Keats (1963), John Keats by Andrew Motion (1998), Stanley Plumley’s deeply felt meditation on Keats, Posthumous Keats, Nicholas Roe’s meticulous John Keats (2012), and Denise Gigante’s The Keats Brothers: The Life of John and George. I have not yet read, but would be remiss if I did not mention, George Keats of Kentucky: A Life, by Lawrence M. Crutcher (2012).

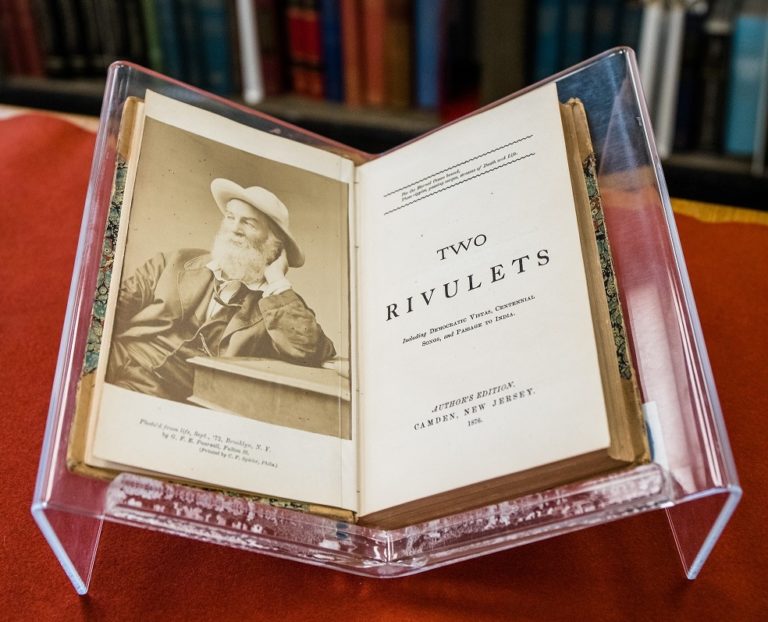

The earliest Keats biography was The Life of John Keats: A memoir by Charles Armitage Brown. Brown worked on it intermittently and sadly from 1829 until 1841. He never published it, but sent it to Richard Monckton Milnes who incorporated much of the material into his 1848 Life, Letters, And Literary Remains of John Keats, digitally available in a PDF format. Other earlier biographies include Sir Sidney Colvin’s 1917 John Keats—His Life and Poetry, His Friends, Critics and After-Fame, (digitally available here), and Amy Lowell’s two-volume John Keats (1925).

The following sites are also helpful. The invaluable Harvard Keats Collection contains what for me is the treasure of a Severn sketch of a stark, dying John. This drawing, unlike Severn’s famous Keats deathbed drawing (“28 Janry 3 o’clock mng. Drawn to keep me awake – a deadly sweat was on him all this night,”), is not in any of the Keats books or sites that I know of. As a bonus, the Harvard drawing contains, too, apparently, a list in Severn’s hand of the books he and Keats were respectively reading or seeking. Other helpful sites are Keats House, Hampstead; Keats-Shelley House, Rome; and English History—Keats.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.3 (Summer, 2016).

Steve Kronen’s poetry collections are Splendor (2006), and Empirical Evidence (1992). His work has appeared in The New Republic, The American Scholar, Poetry, Agni, The American Poetry Review, Little Star, The Georgia Review, Ploughshares, Slate, and The Yale Review. He has received an NEA, three Florida Individual Artist fellowships, the Cecil Hemley Memorial Award from the Poetry Society of America, the James Boatwright Prize from Shenandoah, and fellowships from Bread Loaf, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conferences. He is a librarian in Miami, Florida, where he lives with his wife, novelist Ivonne Lamazares, and their daughter, Sophie.