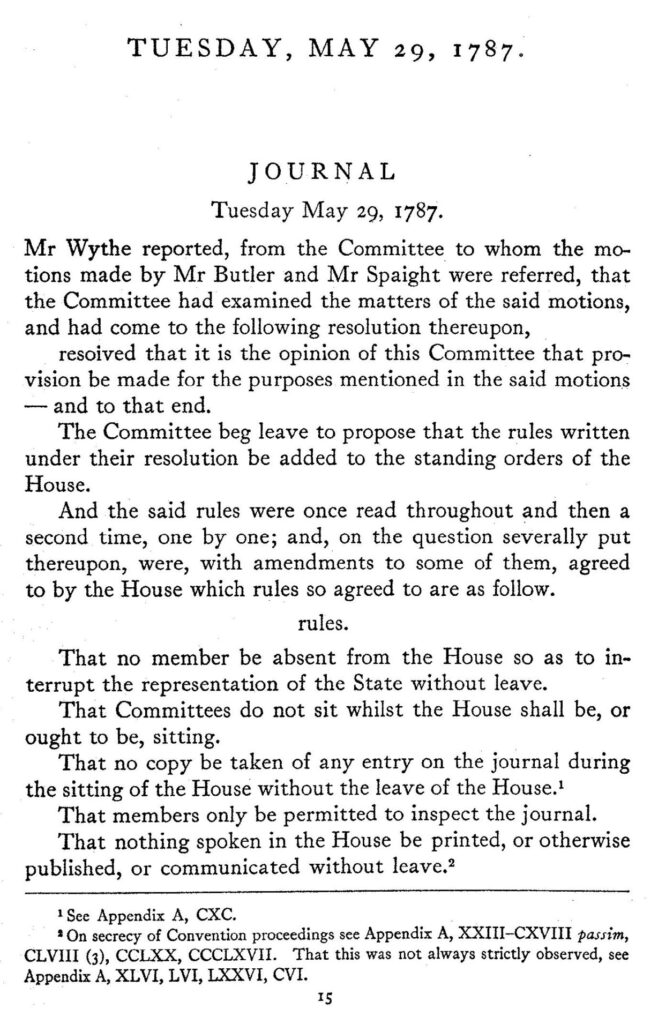

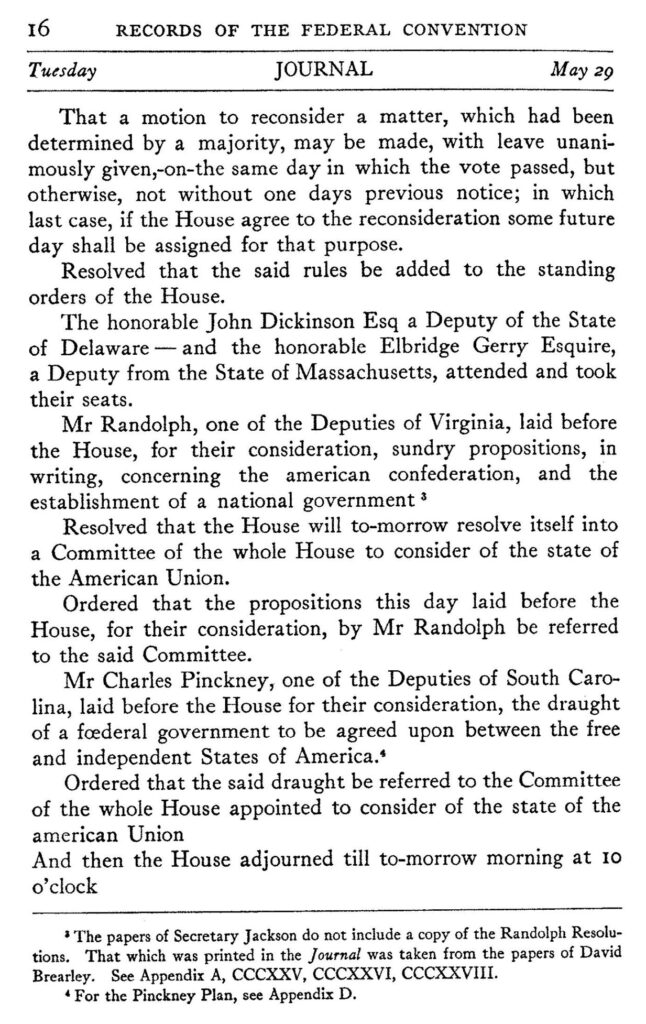

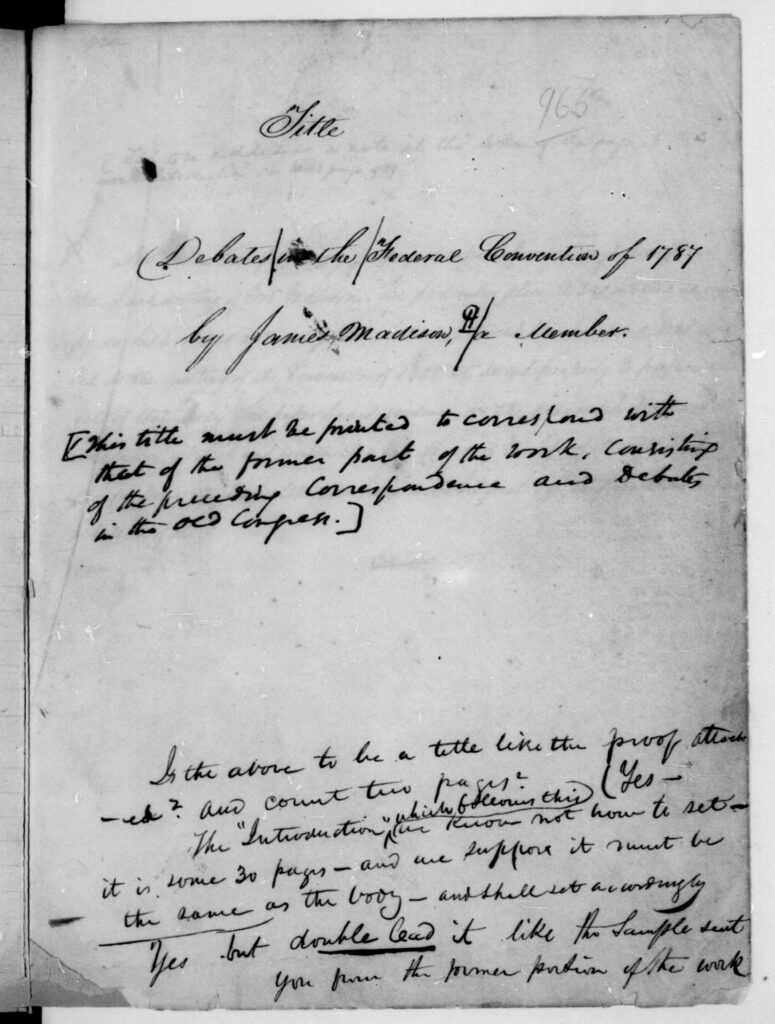

This can open a thoughtful conversation not only about how historians work and write, but also about how the Constitution is interpreted and the difference between history and law. The exercise generates questions about the role of conjecture in historical writing, particularly how historians attempt to account for gaps in the sources and build narratives to capture things like the mood of a room when the evidence doesn’t explicitly lay it out. We talk about whether a historian is responsible for indicating when something is conjecture in writing, how they can do this, and the extent to which they must walk the reader through their process.

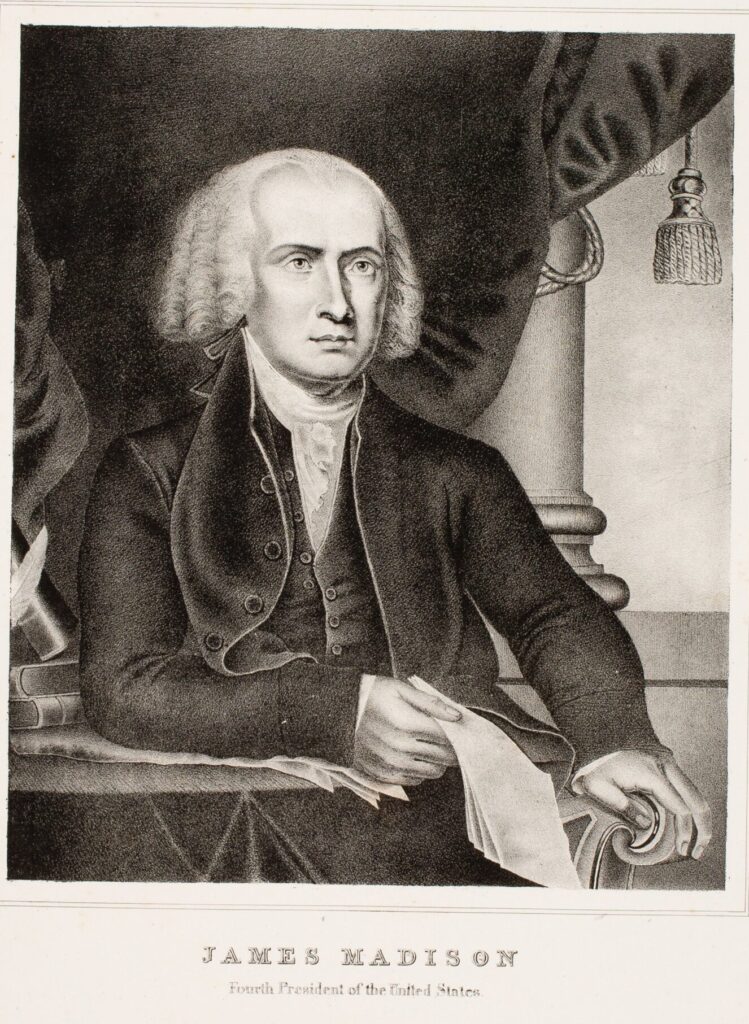

Getting students to closely consider the available notes from a single day of the Constitutional Convention proves to be an engaging way to talk about the challenges of using primary sources to build a narrative of the past. More specifically, it can also give rise to questioning how the Constitution gets interpreted legally, particularly through the framework of originalism. Most students walk away convinced that it’s a lot harder than it might seem to know what the framers were doing or thinking over the summer of 1787. If it’s the only takeaway from the class, it’s a worthwhile one.

Further Reading

Max Farrand, ed., The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, 3 vol. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1911).

Katlyn Marie Carter, Democracy in Darkness: Secrecy and Transparency in the Age of Revolutions (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023).

Mary Sarah Bilder, Madison’s Hand: Revising the Constitutional Convention (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2021).

Carol Berkin, A Brilliant Solution: Inventing the American Constitution (New York: Harper Collins, 2002).

This article originally appeared in February 2024.

Katlyn Marie Carter is an assistant professor of History at the University of Notre Dame. She is the author of Democracy in Darkness: Secrecy and Transparency in the Age of Revolutions (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023).