Baltimore | Boston | Charleston | Chicago | Havana

| Lima | Los Angeles | Mexico City | New Amsterdam | New Orleans

Paramaribo | Philadelphia | Potosi | Quebec City | Salt Lake City

Saint Louis | Santa Fe | San Francisco | Washington, D.C.

In the early 1760s, when María Dolores Quispilloc and her husband Antonio Martínez, together with some of their neighbors, left their community of Sicaya, in Huarochiri, Peru, they carried their few belongings with them. Their most precious item was a mule María Dolores had brought to their marriage as a dowry. On mule back, after four days of tiring travel on small and narrow dirt paths, María Dolores and Antonio arrived at the east gate of the city of Lima.

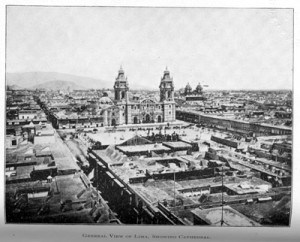

Lima, the City of the Kings (Ciudad de los Reyes), the Peruvian viceroyalty’s capital city, was founded in 1535 by Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro. By the time María Dolores and Antonio arrived, Lima was one of the largest cities in the world, counting around fifty thousand inhabitants. Blacks, mulattoes, Indians, and whites coexisted in a walled space of ten square miles, with many houses, churches, and public buildings divided into six parishes (Santa Ana, San Marcelo, San Sebastián, San Lázaro, Cercado, and Huérfanos). On bullfight days, during promenades, and at the market, people from all colors and social standing mixed together.

Peasants and herders from Huarochiri like María Dolores and Antonio were not newcomers to the city. For many years, huarochirinos had provided food and cloth for city dwellers. Beginning in the second half of the eighteenth century, the population in the Peruvian viceroyalty began to slowly increase after epidemics brought by the Spanish conquistadors in the sixteenth century had killed thousands of people. A growing population, especially in rural areas, meant that land became scarcer. Matters grew worse when in the 1760s, severe droughts made agriculture impossible, especially in the central highlands. Many indigenous people living in peasant communities and on haciendas in the provinces nearby Lima were forced to leave their homes and find new ways to eke out a living. Some of these peasant families had lived in the highlands from a time even before Spaniards set foot on Inca territory. One of the provinces most affected by the droughts was Huarochiri, located about fifty miles east of Lima. Some Huarochiri peasants migrated to other communities in the highland; some hoped to find a means of survival in the city.

What happened to María Dolores and Antonio in Lima tells a good deal about life in this dusty, sprawling urban center toward the end of the eighteenth century. As they encountered people at work and on the streets, their interactions revealed much about the kinds of people living in Lima, and ways in which people interacted with ecclesiastical and colonial state institutions. Our story is a composite, but it may well have been this way.

When María Dolores and Antonio traveled to Lima, they were not carrying produce to sell and then return to their community; this time they came to stay. Asked by two royal soldiers about their whereabouts, they retorted in Quechua (the Indian native language), hoping that the pardo (partially black) soldiers would not understand their native language. María Dolores and Antonio pulled out their baptismal records and an old letter signed by their cacique back in Sicaya, the documents that had saved them many times before, and pointed out the words indicating their destination: “Plaza de San Francisco,” the bustling market place in front of the church of San Francisco, in the eastern part of the city that carried the same name in Spanish and Quechua. The soldiers, used to seeing many Indians coming to the plaza, let them pass.

At the Plaza de San Francisco, where they had sold their produce in earlier years, they knew they would find María Dolores’s aunt at her market booth, where she sold vegetables she had early that morning bought from hacienda laborers at the nearby tambo (a small hut-like house in the outskirts of the city, used to buy and sell produce, and also used by travelers as a resting place) next to the city wall, in the Cercado parish. María Dolores’s aunt, Doña Josefa, lived among Indians and mestizos in the same El Cercado parish.

Lima’s most prominent and richest people lived around the central plaza, the main square of the city. The plaza–following the Spanish grid plan–was surrounded by blocks of houses belonging to the viceroy, the audiencia (city council) and cabildo (town council) members, the archbishop, the members of the aristocracy, and some rich merchants. The further removed from the central plaza one lived, the lower one’s economic and social standing. People like María Dolores and Antonio only came to the city’s center when they participated in the lively market at San Francisco, or–dressed in their best clothes–they attended the Sunday promenades in the Paseo de los Descalzos, mostly to see better-off people, less often to be seen, or attended a bullfight in Lima’s Plaza de Acho.

Daily life in the city often was an adventure on its own. The usual Lima winter drizzle–it never rains–had turned the way to the Plaza de San Francisco into a mudded chaos. People wore heavy ponchos or covered themselves with coarsely woven blankets. Gallinazos (turkey buzzards) sat on the ground devouring leftovers and rotten food. The closer María Dolores and Antonio came to the plaza, the louder the voices became. Indians were selling their produce, blacks and mulattoes carried heavy bags they would then take home to their masters. Some black women stood behind wooden tables and large charcoal stoves, iron pans, and ceramic pots preparing food for passers-by.

After wandering around for a while, greeting people they knew from former years, and inquiring about Doña Josefa, they found out that she had not come to the market that day. Her place was empty–the people told them–because she had gone to see the judge at the cabildo. Gossip had it that Doña Josefa had had a word-fight with her neighbor in El Cercado, in which one had called the other a “wrecked dark-skinned witch” and a “lover of Black men and a prostitute.” A Doña, like Doña Josefa, could not leave such insults uncontested, and she had sued her neighbor for defamation.

In her neighborhood, Doña Josefa was known as a widow, but everyone in the family and in the neighborhood knew that she had never married. Calling herself a widow gave her a certain aura of respectability, given that she had had two children. One of the children had died at age two, the other, José, was now a twenty-seven-year-old single man who lived with his mother, but spent his nights playing cards in the neighborhood bar (pulpería) owned by a divorced (or, rather, separated) mestiza, Asunción. Rumor had it that José and Asunción were “having a sinful relationship.”

After María Dolores and Antonio heard about all this, in varied versions, they decided to return to El Cercado to find their aunt. They had no address, because there was none, but they remembered where Doña Josefa’s little adobe house was located, and they also remembered that neighbors would call the place the esquina de los suspiros (the sighing corner). When they knocked at the wooden door, Doña Josefa opened. She was wearing her Sunday clothes, and she resembled one of those poor Spanish seamstresses whom one could see on Lima’s streets covering their faces with a black shawl (tapadas). Doña Josefa asked them in and took a seat at the table. María Dolores and Antonio told her about their plights back in Sicaya, and asked for help, while pulling out a large tocuyo (coarsely woven cloth) bag with potatoes they had brought as a gift. Those potatoes, they explained, were once meant to be the seeds for a new crop.

Doña Josefa offered to take María Dolores and Antonio, and their mule, to a nearby hacienda, where she would–once again–buy vegetables from hacienda workers and bring them to the Plaza de San Francisco. She would provide them with a few pesos to purchase the vegetables. With the earnings they obtained they were eventually to repay this initial loan. With a plan in mind, they extinguished the candle on the table and, wrapped in a blanket, went to sleep, Doña Josefa in her bed, María Dolores and Antonio on the dirt ground in the corner of the small kitchen.

Before the sun came out the next day, Doña Josefa, María Dolores, and Antonio were on their way to the nearby hacienda, and three hours later, at 7 A.M. they were laying out their freshly bought vegetables on a cloth on the ground at the Plaza de San Francisco. By noon, everything was sold, and most vendors began collecting their belongings. Gradually the smell of fresh fish and vegetables changed into the smell of cooked food.

At the outskirts of the market place, some black women were preparing traditional dishes in the open air to sell. They had well-known specialties to offer, like anticuchos and cau-cau. Most of these black women were slaves. With the money obtained from selling their specialties, they paid a daily jornal to their owners at the end of the day. If they sold more than the stipulated jornal, they could keep it; if they sold less, they had to make up the difference. This system gave many slaves some kind of freedom in their daily deals, away from the vigilant eye of a master.

María Dolores was especially jealous of a mulatta, Manuela, who sold cau-cau. Every time they had come to Lima in the previous years, her husband would visit Manuela’s booth to try her cau-cau. Nearby vendors had already been gossiping about a possible amorous entanglement between Manuela and Antonio. This time, too, Antonio walked over to see Manuela. Antonio soon found out that Manuela had changed “hands.” While she had once belonged to a merchant who had a store at the Calle de Bodegones, Lima’s main commercial street at this time, she now had been bought by a poor widow in the parish of Santa Ana. Manuela told Antonio about how she had managed to rid herself of a master who was severely mistreating her whenever she could not come up with the money to pay her daily jornal to him, and how he insistently requested sexual favors. Tired of these abuses, Manuela had sought for help in a black brotherhood (cofradia), where many slaves and former slaves originally coming from West Africa had found a place to gather. The queen of the brotherhood was Manuela’s godmother, and she had offered to help her write a legal complaint against her owner and then to bring it to the judge in the cabildo. Fortunately, the merchant did not object to Manuela’s transfer to a new owner as long as he obtained the price she was worth according to her conque (a written certificate each slave had indicating his/her price, abilities, and age). The widow–her new owner–paid five hundred pesos to the merchant, a price that was above the average price of male and female slaves in the city, because Manuela was relatively young (twenty-three), healthy, and had some sought after cooking skills and a booth to sell food.

In their conversation, Antonio also found out from Manuela that the widow lived off what Manuela provided her. This widow, Doña Encarnación Samudio, had been married to a lower colonial state bureaucrat, a scribe of the cabildo, Don Maríano Ugarte. Doña Encarnación had never worked, and to continue to be perceived by her neighbors as a decent mestiza, she was not supposed to. When she was widowed after seventeen years of marriage, she was left with little money and no state pension. Her only recourse was to invest what little she had to make someone work for her. Manuela soon found out that Doña Encarnación, aside from herself, also possessed a small track of land, not too far away from the city, and that since her husband had died, the land lay bare.

While Antonio was talking to Manuela and enjoying some cau-cau served in a little pottery dish with a wooden spoon, María Dolores had remained behind. Soon she found herself surrounded by barefoot children teasing her about her Indian clothes. When Antonio found her, he chased away the children mumbling some words about respect to elders.

It had been a long day, and María Dolores and Antonio decided to return to El Cercado. Soon after they left the plaza, they noticed that someone was following them. It was a tinterillo (an apprentice lawyer trying to make some money) eager to find out if the couple had some complaint to file in the city courts. He offered to help for a small price. María Dolores remembered her aunt’s quarrel with her neighbor; Antonio remembered Manuela’s writing to the judge. Neither María Dolores nor Antonio really understood what all this meant. Never before had they had any encounter with the judicial system, and now–in one day–they had heard two stories that involved the judiciary: the aunt’s defamation case and Manuela’s change of ownership. By then, the only thing they knew was that their cacique back in Sicaya had always been very adamant about a pile of papers–in which, as people in the community knew–it was said that the land they lived on rightfully belonged to the community of Sicaya. The file carried Phillip II’s signature.

The next day, after selling the produce at the market, Antonio went to see Doña Encarnación following Manuela’s indications. Doña Encarnación lived in a small white painted adobe house, next to the church of Santa Ana. He used the heavy iron handle to knock at the worn-out thick wooden door. After many minutes, Doña Encarnación looked out of the window, hiding behind some neatly embroidered drapes. Antonio took his hat off, and respectfully greeted her, indicating he wanted to talk to her. Many more minutes elapsed before Antonio heard the cracking front door slowly opening. Antonio explained why he had come to see her, and told Doña Encarnación that Antonia had told him about the track of land she had. Portraying himself as a successful peasant, he convinced Doña Encarnación to show him the piece of property.

When Antonio came back the next day, he brought the mule and a shovel with him. Doña Encarnación and Antonio walked for about two hours before they reached the track of land, surrounded by other tracks of land and a larger sugar hacienda. A few bushes and much weed lay before them, but the land was good, and it was time to get the field ready to plant. Thus, Antonio and Doña Encarnación agreed that Antonio could get the fields ready and they would split the proceeds in halves (al partir).

Antonio admired the sugar fields and he also knew that it was a good crop. Sugar was consumed in Lima, but more sugar was shipped to Santiago. Prices one could obtain for sugar were high. During the next days, Antonio left the marketing of vegetables to María Dolores, and he began cleaning Doña Encarnación’s field and talking to the neighboring yanaconas (sharecroppers) of the hacienda to find out how and when to begin planting sugar cane. Soon, the hacienda-owner, Don Felipe Santisteban, a former Spanish militia captain, learned about Antonio’s plans, and offered his sugar mill to grind the cane after Antonio brought in the crop. He also explained to him that many small producers brought their cane to his mill because he had the only mill for miles around. For the use of the mill, he would retain 20 percent of the net sugar produced. What he did not tell Antonio was that over the last ten years some small farmers had accumulated debts with him and had been forced out of their land. By absorbing adjacent plots, like Doña Encarnación’s, the hacienda had become ever larger. Moreover, the initial work of cleaning the fields had been done by the farmers and had not cost anything to Don Felipe.

María Dolores and Antonio began working on the land, cleaning, making furrows, and hoping for some rain. One Sunday morning while working on the plot, they saw a black-dressed man on a horse and with a book under his arm approach them. As the man came closer, they recognized the man was a priest. He introduced himself as Don Felipe Sotomayor, and explained that he was coming from a mass he had just held in the small hacienda-chapel, remarking that he had not seen them, either in the El Cercado church or in the hacienda-chapel. Thus, he continued, he needed to remind them of their Christian duties, to confess, take the Holy Communion, and attend mass. María Dolores and Antonio lamented their lack of time. The priest was angry and accused them of disrespecting God and living in sin. Both agreed to attend mass the coming Sunday. Don Felipe then blessed the small plot of land, and told them that thanks to his blessings, God would protect them and that when the time had come, he would hope that in gratitude to his blessings, they would provide him with a share of their crop.

As they continued talking, the priest found out that María Dolores and Antonio–although married in Sicaya by the priest of Huarochiri–had not been married following strict Catholic prescriptions: no banns had been read to find out whether there was an impediment to marriage, which in turn would have required a church-issued dispensation. Moreover, María Dolores’s and Antonio’s fathers had not offered their written consent to the marriage, and neither was María Dolores’s consent to marriage recorded anywhere. Of course, María Dolores and Antonio had no idea what the priest was talking about. They had been living together for three years and had counted, until then, on the approval of their priest and their community. In the community, back in Huarochiri, they had seen a priest once or twice a year, and they had attended the mass he had offered on the little village plaza, often not understanding the priest’s Latin mumbling. But because the priest, like their corregidor (local state bureaucrat) was a white man, they felt compelled to at least be there and listen. Now they had a priest in front of them, telling them not that mankind had to redeem its sins, but that they were living in sin. The priest understood their confusion; it was not the first time he witnessed troubled faces. Before Don Felipe left–during the whole conversation he sat on his horse–he reminded them to come to church the following Sunday.

When María Dolores and Antonio were sitting on the bench outside the church the following Sunday, they noticed that some other couples–looking very much like themselves–were sitting on the next bench or nervously wandering around. They heard some couples speaking in Quechua. Very soon they found themselves talking to each other, wondering about what the priest would tell them. While they were waiting for the church doors to open, they had time to exchange some life experiences, some doubts, some thoughts. All of them had quite recently come from different smaller communities in the surroundings of Lima. Some–as María Dolores and Antonio–had escaped droughts, another couple had been expelled from their land by a neighboring hacendado, another couple had been asked to increase their tribute payment by their cacique, another couple had barely escaped being recruited for mita labor (draft labor) in an obraje.

When the priest appeared at the church door, he invited all couples to come in. Their conversation came to an end, and they found themselves sitting on the dirt ground of the small church. The priest stood in front of them on a little wooden platform. Behind him was a colorful wood-carved altar with a cross and Jesus. The priest asked them to kneel and thank God for allowing salvation. He proclaimed himself as the mediator between God and sin, and underlined his intentions of rescuing them for heavenly life after death.

Before that time, although María Dolores and Antonio knew many struggles lay ahead of them, they had only begun to sense what it meant to live in Lima, a world so different from their own. They also knew there were many sides to the city, as much as to its people.

And whatever happened to María Dolores, Antonio, Doña Josefa, and Manuel? Ten years later, that is around 1770, Indian uprisings in the countryside had swelled all over the viceroyalty, and between 1780 and 1783 the massive Tupac Amaru II uprising took place, an Indian-led revolt in which more than one hundred thousand people died, about 7 percent of the viceroyalty’s total population. It was the beginning of decades of military actions until the wars of independence ended in 1825.

After Don Felipe ousted Antonio and Doña Encarnación from their plot of land, Antonio became an apprentice to a free black shoemaker in the city, where he worked seven days a week for fourteen hours each day. He did not earn a salary, and was paid with shoes instead, forcing him to sell the shoes in order to obtain money. During the Tupac Amaru II rebellion, he was drafted into the Spanish army then sent to quench the rebellion in Cusco. For Antonio it was the first time in his life that he had to leave his Huarochiri-Lima route. By 1782, María Dolores was a widow with one child (two others died in early infancy) blessed with all the church’s requirements. The priest, a Jesuit, who had induced her to do so, was removed and returned to Spain after the Spanish Crown expelled the order from its colonial dominions in 1776. For several more years, María Dolores continued to sell vegetables with her aunt at the Plaza de San Francisco. Manuela finally obtained her liberty when her owner died and in her will granted freedom to Manuela for “her good and faithful services.” The sugar hacienda owner was struck by destiny much later, when in the wake of the wars of independence, his yanaconas escaped, and the few slaves who also labored on the hacienda joined General Jose de San Martin’s army upon his promise that all slaves participating on the patriot side would be freed. The armies ransacked the hacienda and destroyed the sugar mill, and for many years no sugar was produced. What little Don Felipe could rescue, he took with him to Spain.

This article originally appeared in issue 3.4 (July, 2003).

Christine Hunefeldt teaches Latin American history at the University of California, San Diego, and is the author of Paying the Price of Freedom: Family and Labor Among Lima’s Slaves, 1800-1854 (Berkeley, Ca., 1994) and Liberalism in the Bedroom: Quarreling Spouses in Nineteenth-Century Lima (University Park, Pa., 2000).