In the two centuries since George Washington’s death, his papers have slowly made their way into the government’s hands and ultimately into the Library of Congress. In 1964 the Library made them available outside its reading rooms by having the entire collection microfilmed. Today, those papers, some 65,000 documents, are available online at the Library’s Website, American Memory: Historical Collections for the National Digital Library. The years I spent coordinating the digitization of Washington’s Papers sometimes reminded me of his spring 1748 journey into the wilderness of Virginia and Maryland surveying uncharted territory. The project was the first at the Library of Congress in which digital images were created from microfilm, and the database was derived from a published index, which itself had been created using keypunch cards from a much earlier computer technology.

Reading the Washington Papers online is much easier than traveling to Washington and meeting requirements to use the Library’s reading rooms, which include obtaining a Library identification card, being at least eighteen years of age, and, if an undergraduate, providing a letter of introduction from one’s academic advisor. And, using the Website is probably still less burdensome than finding a library that holds the microfilm or can obtain it through interlibrary loan. Scholarly research continues to be done in the new electronic medium. The George Washington Papers documentary edition project at the University of Virginia now uses the Library’s George Washington Papers online for their research. Their series, The Diaries of George Washington, 6 vols. (Charlottesville, 1976-79), is available on the Website, accompanying the Library’s manuscript diary volumes. This combination of images of the original manuscript documents and searchable annotated transcriptions makes the Washington Papers a rich resource for research in almost every aspect of colonial and early American history, from the American Revolution to gardening and agriculture, from slavery to the eighteenth-century concept of the gentleman, from the Constitutional Convention to genealogy and local and regional history. But also possible now are activities for which most reading rooms do not have the luxury of space and staff—at least not for a lot of people all at once. People can come to the Washington Papers Website to page through his letterbooks or diaries, letting curiosity lead the way. Or, they might visit the site to find out what a manuscript collection is, exactly. A teacher might search for and download an item to illustrate the contents of a lesson plan. Encountering so many different kinds of primary sources in varying formats in American Memory‘s historical collections generally, such a lifelong learner might then venture further, not just to other Websites but to related historical resources, such as museums and historical sites, or perhaps seek out published documentary editions, biographies, or histories listed in Related Resources and bibliography pages, or to the library or repository the next town or county over, of which they had previously known little or nothing.

In February 1998, when the Washington Papers went online, there were twenty-seven collections on the American Memory Website. Today, there are over a hundred, with more to come. The Thomas Jefferson Papers and Abraham Lincoln Papers are now completely online, and the James Madison and Andrew Jackson Papers will follow over the next several years. Other manuscript collections include the Samuel F. B. Morse Papers, the Alexander Graham Bell Family Papers, and the Frederick Douglass Papers. Large online book collections cover the regional history of the United States. Some collections were originally acquired through federal funding during the Great Depression, including American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1940, interviews and personal histories of ordinary people from twenty-three states, and Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938 comprising twenty-three hundred first-person accounts of slavery and hundreds of photos of former slaves, and more. Then there are the collections of contributing libraries, historical societies, and repositories, funded by a special program from 1996 through 1999. These include Westward by Sea: A Maritime Perspective on American Expansion, 1820-1890, from the Mystic Seaport Museum and the G. W. Blunt White Library; The Church in the Southern Black Community, 1780-1925 from the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill; The First American West: The Ohio River Valley, 1750-1820, and many more.

It’s now possible to explore topics across multiple collections and discover a range of substantively different sources. For example, if you were to search across American Memory collections on the phrase “Shays’ Rebellion”—the insurgency of western Massachusetts farmers that took place in late 1786 through early 1787—you would find in the Washington Papers correspondence between George Washington and Benjamin Lincoln, who commanded the Massachusetts militia sent against Shay and his men, and Massachusetts governor James Bowdoin and his successor John Hancock, and a February 7, 1787, letter from Ezra Stiles with a sketch of the area of Shays’ operations. In The First American West: The Ohio River Valley, 1750-1820 you would find a lengthy letter from John Marshall to James Wilkinson outlining all the “contradictory accounts of the motives & views of the insurgents” that were circulating at the time. An American Time Capsule: Three Centuries of Broadsides and Other Printed Ephemera would turn up several contemporary broadsides issued to the populace by Boston selectmen and by John Hancock, and The Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation would yield documentation in the Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789. But you would also be able to do a little historiographical research into Shays’ Rebellion, as both the Atlantic Monthly and Harper’s New Monthly Magazine from The Nineteenth Century in Print: Periodicals offer some nineteenth-century essays interpreting Shays’ Rebellion. Of course, researchers will want to consult resources beyond those offered by American Memory. What American Memory offers are unique historical collections not otherwise accessible or well known to teachers, students, and those interested in history.

We know a good deal about how many people visit the American Memorysite, from a record of “hits” that anyone can view. We’d like to know more about how they use the material they find here. Reference questions submitted electronically through our “error report” and “question/comment” forms accessible on the FAQ page give us some idea. They are statistically incomplete since many people use the collections without ever communicating with the Library. But they help us gain a broad sense of how things may or may not have changed in the world of historical interests and research with the advent of the World Wide Web.

Reference queries tell us that people have several inaccurate expectations about American Memory. Many of these are understandable. People expect to find in American Memory every kind of historical documentation possible on every aspect of American history, and they communicate their surprise at discovering otherwise. This is a popular expectation of the Internet—that it is easy to put “stuff” online, that everything is or will be soon be there, and that the Internet can therefore stand alone as a universal information resource, which, of course, for historical research is not the case.

Others approach the site as a kind of encyclopedia where you can look things up and are, again, surprised that this is not the case. In a related manner, people think of American Memory as the Website of the nation’s library and a place to pose all kinds of questions from the historical to the practical. This concept of the Library is not new, although e-mail and the Internet make it easier to pose questions from every geographical area of the nation and beyond. Everyone has a favorite reference question, and mine is from a Pacific island resident, who was dependent on a very early model refrigerator that was icing up. He needed information on its original design so he could attempt repairs. His question was referred to the Science, Technology, and Business Division, which if it did not have the information, knew where it could be found.

Whatever the medium, reference specialists want to teach people how to use the Library and find resources, which is as important an educational goal as understanding a particular historical question. As in the “pre-Internet” age, students have difficulty coming up with the proper research term or concept that will get them to the resources they need. How do I find out the differences between my home today and one in the 1800s? Are there any histories of black cowboys in the nineteenth century? How I can find them? What is a definition of political corruption? Where would I find examples from the past? How can false arguments or sources from the past still be of use to historians?

A high-school student is writing a report on the practice of colonial crafts and trades. She should start with some general book or encyclopedia sources on the history of work or of the colonial household where so much of it took place. For online resources, the digital reference specialist suggests she start with the Website of Colonial Williamsburg, which offers texts and resources focused on the history of colonial trades and material culture. Once the student has done her research, the reference specialist suggests she then return to the American Memory Website and search through America’s First Look into the Camera: Daguerreotype Portraits and Views, 1839-1864, which has a number of occupational portraits. She might then challenge her skills by looking at these portraits to see if she can find visual evidence of how some occupations may or may not have changed from the eighteenth to the early nineteenth century. There are lessons on American Memory‘s Learning Page on different kinds of primary sources and how to research them.

Naturally, we see American Memory as a flow of historical collections from the Library of Congress to American citizens everywhere. Unanticipated is the flow of content and information back to the Library of Congress from people who have local history, genealogical, or other specialized information to offer for correcting and enhancing descriptions of items in the institution’s collections. They are seeing these collections for the first time.

Here is a representative sample of the kinds of information users offer. A resident of Tennessee compares a photograph from Selected Civil War Photographs to those available in a local historical society. A view of the “Environs of Knoxville seen from south bank of the Holston River . . . ” is actually from that of the Tennessee River. Another Tennessee resident identifies a Depression-era photograph of a Greenville courthouse as being in Greene not Davidson County, which the user remarks may have had a Greenville too, but he knows the former and can correctly identify the courthouse’s true location. He would like to make sure the photograph is “properly attributed.” A user informs the Library that a photograph in America from the Great Depression to World War II is actually Freedom rather than Conway, Pennsylvania. The buildings in the foreground are still standing, while the first story of a factory in the background survives. She also offers to send photographs to document the information. People recognize members of previous generations of family or local figures as well as regions, counties, and hometowns. A daguerreotype of “Three unidentified men,” 1853-55, from Mathew Brady’s studio in America’s First Look into the Camera: Daguerreotype Portraits and Views, 1839-1864 is actually of someone’s great grandfather, his cousin, and a great uncle. While the lack of information is understandable, members of this family are disconcerted to see their forebears described online as unidentified when they are so well known to them.

Understandably, many corrections or additions to bibliographical information are for visual materials: daguerreotypes, photographs, and even film (especially those of early New York). For photographs, the primary source of information for cataloging these has been the original caption supplied by the creator or photographer on the item or in a caption logbook. But the majority of resulting corrections are actually made in a notes field of the bibliographical record displayed online with the item. This preserves the original caption, which is a primary source text itself. Identifying less notable people or places requires extensive research, and the necessary documentation is difficult to find. But now these are more widely available to users with knowledge of people and places. They will sometimes offer documentation, or if not, Library staff now have a name or other detailed information that can be specifically researched. If the outcome is ambiguous, the Library will sometimes add a note to the bibliographical description that there is conflicting information.

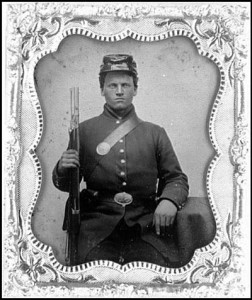

People also have specialized knowledge to offer. In the Selected Civil War Photographs, 1861-1865 collection, for example, a photograph has the supplied title “[Portrait of a Federal Soldier]” in the bibliographical record because of the general appearance of his uniform (see fig. 3). However, a user e-mails, Check his belt buckle. Soldiers recycled enemy uniforms and articles of clothing from battlefield victims. But to avoid being misidentified themselves, a Confederate soldier, for example, would turn a recycled Union soldier’s belt buckle upside down, which the user believes appears to be the case in this portrait. He also offers clues related to the rifle the subject is holding. The supplied title is changed to “[Portrait of a Soldier]” until these clues can be researched further.

American Memory‘s Today in History page also generates responses from sharp-eyed users. This page features events keyed to each day in the calendar, offering a short essay and links to related collections. It functions as a handy introduction to the collections in American Memory. The items featured are a mix of familiar “blockbuster” and lesser-known events, and perhaps this latter is what makes the page so interesting to users. The patenting of the first cable car in 1871 shares the date January 13 with the birth of Benjamin Franklin in 1706. Alongside the ratification of the Treaty of Paris in 1784, formally establishing the United States as an independent and sovereign nation, are the birth of novelist, folklorist, dramatist, and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston and the opening of the New York Stock Exchange’s first permanent headquarters at 10-12 Broad near Wall Street in New York City. The essays branch off into related topics, providing links along the way to collections online that illustrate or extend the subject matter.

A user notes, correctly, that a paragraph in a Today in History feature for February 8 on Jules Verne refers incorrectly to Civil War “hot air balloons,” since hydrogen gas, derived in a complex process described by the user, was used to fuel these balloons, not hot air. Another asks, would it be more accurate to say that Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was born in Portland, Massachusetts, on February 27, 1807, since Maine was not yet a state? Anne Hutchinson did not move to Long Island but to what is now Westchester County, a user writes, also noting today’s Hutchinson River Parkway which passes near where she lived. Surely the sun does not “move north across the celestial equator,” a user e-mails about a March 20 Today in History feature on the vernal equinox, but rather it appears to move. In another Today in History feature, two different Maryland residents catch an incorrect reference to Ellicot City as Endicott City.

And, of course, people raise issues of interpretation. The film collection Spanish American War in Motion Pictures, for example, generated a number of e-mails from users on how better to characterize the war in the Philippines in 1899, which had been subsumed under the 1898 Spanish-American War on the Website. The subject specialists who wrote the special presentation for the Website had used the Library of Congress subject heading term “insurrection” to describe the war in the Philippines. Although the term had been employed in many reputable sources, those who e-mailed thought it was outdated. After discussions among staff, the term “insurrection” was changed to “revolution” on the homepage and in the special presentation. But the two events remained grouped together since they had been organized and programmed on the server as one collection. Such comments are almost always offered in a spirit of historical inquiry and raise questions that might not otherwise be addressed if these collections had not gone online. The questions are discussed via the in-house e-mail reference list, but also in informal conversation and sometimes in meetings.

Who are these people who send queries, comments, corrections, and bibliographical information? We know something far more important about them than any demographic information might provide. They are attentive, reading, thinking users of online historical content. Even e-mail reports of typos and minor discrepancies are, after all, the byproduct of close attention to items in the collections. One cannot help but be struck by the contrast between this and popular expressions of concern about the deleterious impact of the Internet as a whole on our attention span and on thinking itself.

For many people the Library of Congress has long been a remote institution. That is certainly less the case now as a broader community of researchers learns about its reading rooms and custodial divisions, browses, researches, and moves about in its collections. How will it all turn out? We are still in the middle of the history of the Internet, so it is difficult to say. Perhaps, for now, we might be guided by George Washington’s account of his 1748 journey over the mountains. He tersely closed his diary with the observation that he had returned home safe. But we know, of course, he did not stay there for long. And neither will we.

This article originally appeared in issue 3.2 (January, 2003).

Laura Graham received a Ph.D. in history from the University of Rochester in 1993. She has worked at the Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society; the Henry Laurens Papers, University of South Carolina; and currently is at the Library of Congress.