Now that our campus (like so many others) is resuming in-person living and learning, I continue to ruminate on what lessons from the sudden remote turn will we carry forward, and which elements we will gladly leave behind. I recently discarded the hand-sewn mask I clumsily fashioned from a dishtowel in the spring of 2020, using the sewing kit I inherited from my late grandmother. Others are similarly deaccessioning—or preserving—the material traces of pandemic time. And they are delving into the pedagogical implications of the transformations we have experienced.

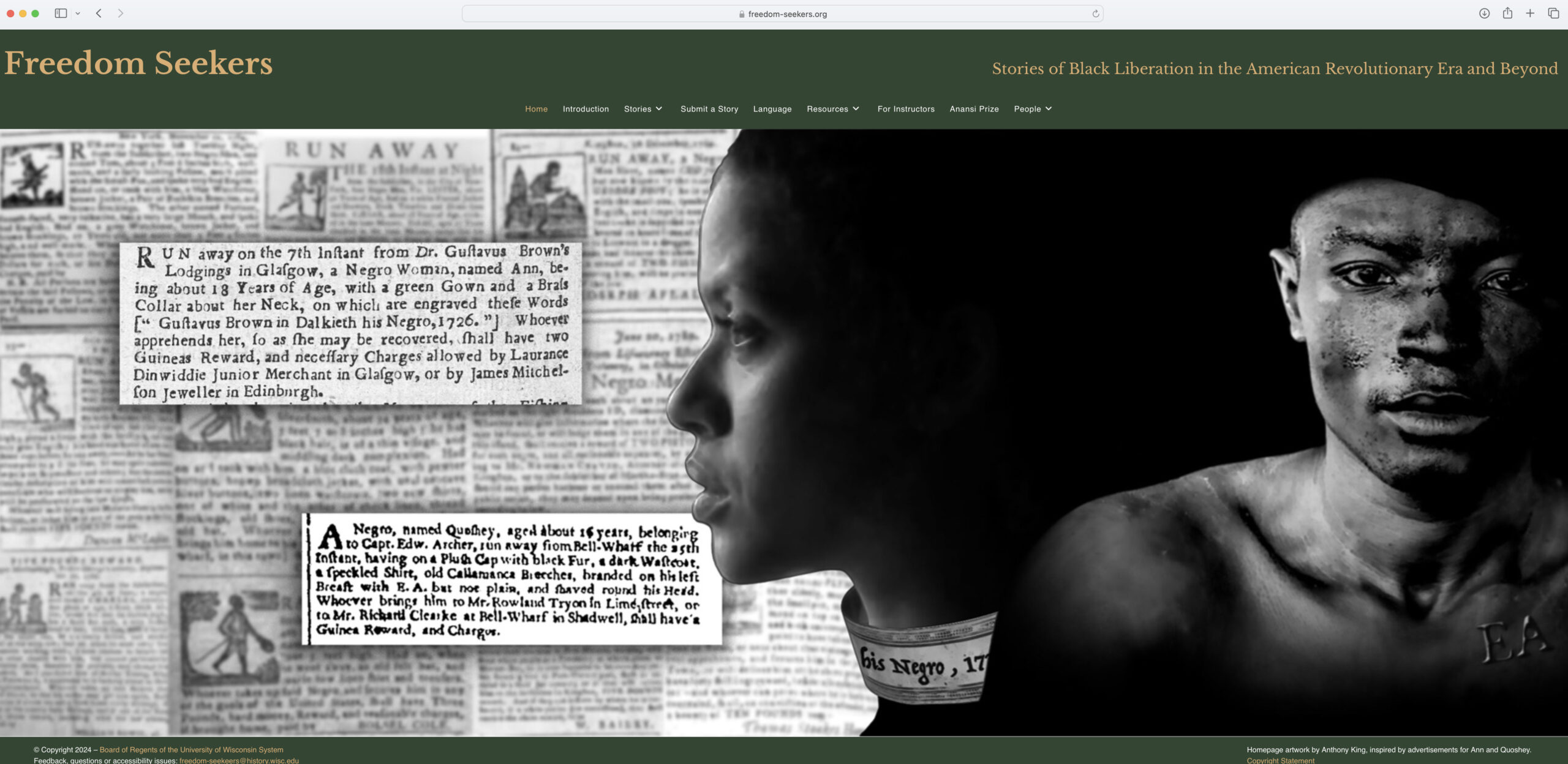

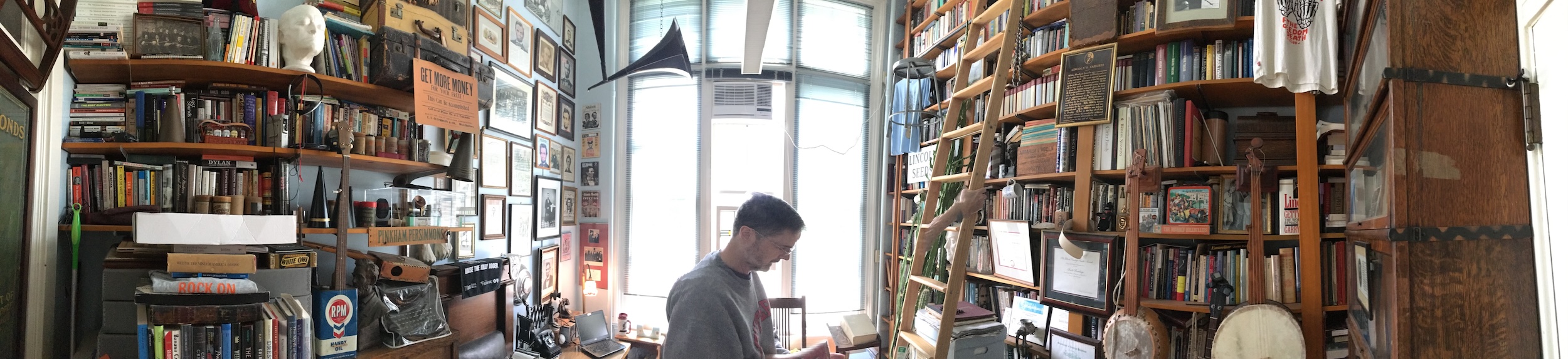

What this means for the future of early America, and of the meaningful materials that endure today, is a matter still unfolding. The experiences of encountering tangible items in real space, as part of an in-person community, are not interchangeable with virtual approaches. But nor is this a simple case of “less than.” Instead, there are striking possibilities for different insights and methods, and even greater attunement to the many people needed to carry forward collaborative learning. I will likely continue to incorporate digital forms of material engagement in my classes in the future because they carry us into alternate relations: with significant items, with the spaces we inhabit, and with each other.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the many colleagues, students, and community members who have collaborated on these topics and offered insights into the practices, politics, and ethics of engaging materiality and the peoples linked to it. Partners at Mount Holyoke College, the University of Massachusetts Amherst, the Five College Consortium, and Williams College have been especially instrumental in the work described here. Ned Cooke, furniture historian at Yale University, taught a graduate seminar on New Haven and American material culture that helped lead me to these fields. Colleagues at American Antiquarian Society and Commonplace previously helped me think through the transits of materiality and heritage items in Indigenous-colonial contexts, and the need for continuing restorative work around repatriation to Indigenous nations in and beyond New England. The work of Akeia de Barros Gomes, Senior Curator of Maritime Social History at Mystic Seaport Museum, has also shaped my thinking.

I am especially grateful to members of “Afterlives of Objects” in Spring 2020 for their patience, care, and permission to reference their work. While space constraints prevent discussion of each project that seminar members created, I wish to acknowledge that every member of that collective learning space contributed insights, critiques, and creativity.

Further reading

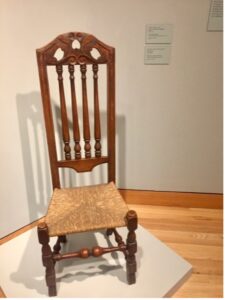

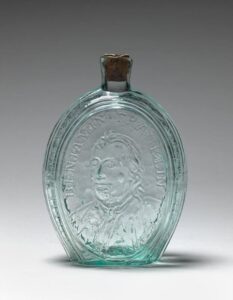

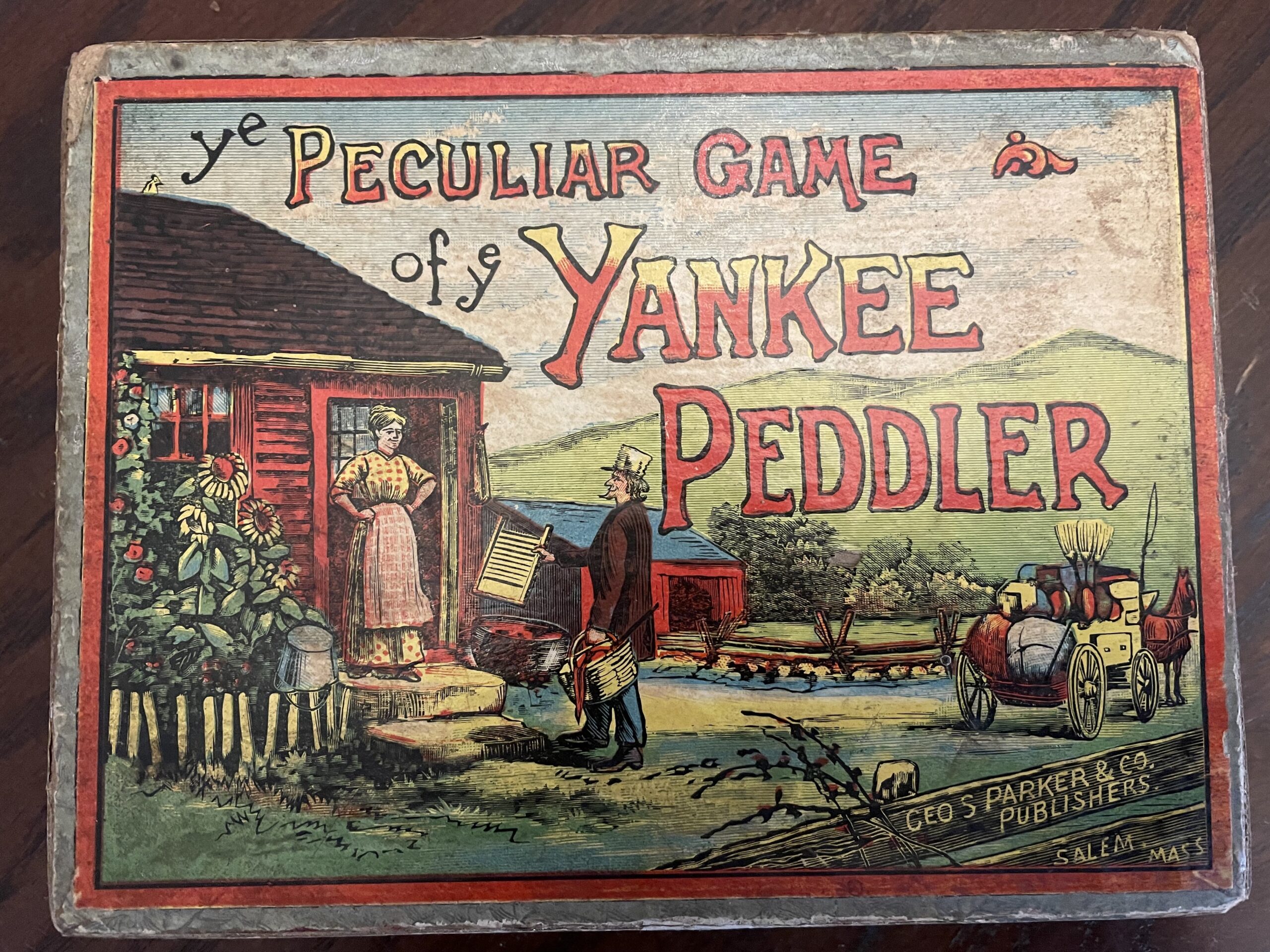

These are a few resources from the “Afterlives of Objects” syllabus that shaped our in-roads into furnishings and other material items, and their contexts both inside and beyond museums: Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, et al., “Introduction: Thinking with Things,” in Tangible Things: Making History through Objects (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 1-20; Fred Wilson and Howard Halle, “Mining the Museum,” Grand Street (no. 44, 1993): 151-72, including three page contextual explanation of the exhibition (170-72); Howard Mansfield, “In the Memory House,” in In The Memory House (Golden CO: Fulcrum Publishing, 1995), 5-20; Nina Simon, selections from The Participatory Museum (Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0, 2010): “Preface: Why Participate?” and excerpts from ch. 4, “Social Objects”; D. Rae Gould, “NAGPRA, CUI and Institutional Will,” in The Routledge Companion to Cultural Property, ed. Jane Anderson and Haidy Geismar (New York: Routledge, 2017), 134-51; James Deetz and Patricia Scott Deetz, “A Few Things Needful: Houses and Furnishings,” in James Deetz and Patricia Scott Deetz, The Times of Their Lives: Life, Love, and Death in Plymouth Colony (New York: Anchor Books, 2000); Elaine Sesma, “‘A Web of Community’: Uncovering African American Historic Sites in Deerfield MA,” Journal of Community Archaeology and Heritage 2 (May 2015): 121-36; R. Eric Hollinger et al., “Tlingit-Smithsonian Collaborations with 3D digitization of Cultural Objects,” Museum Anthropology Review, 7 (Spring-Fall 2013): 201-53; Yale University Art Gallery, film clip, “Studying American Furniture in the Present,” 49 min.

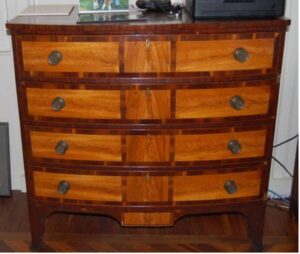

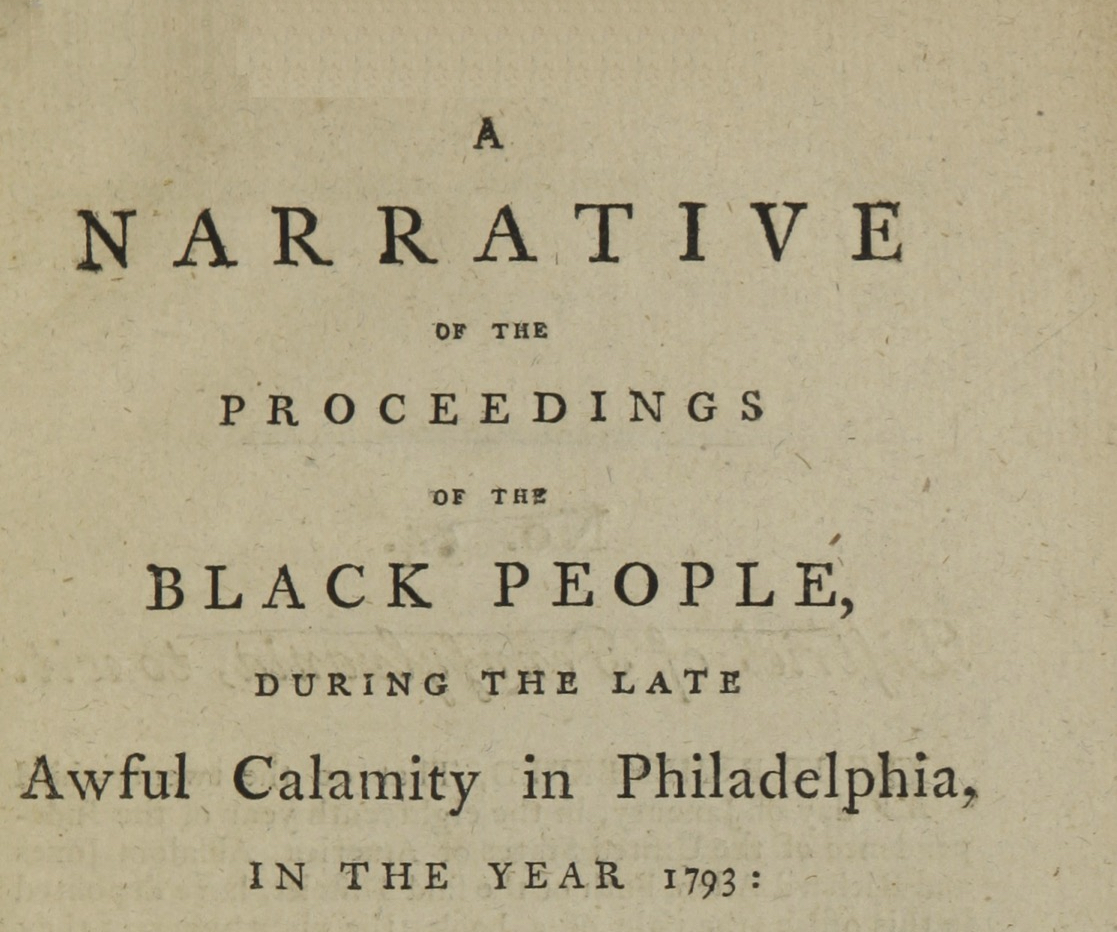

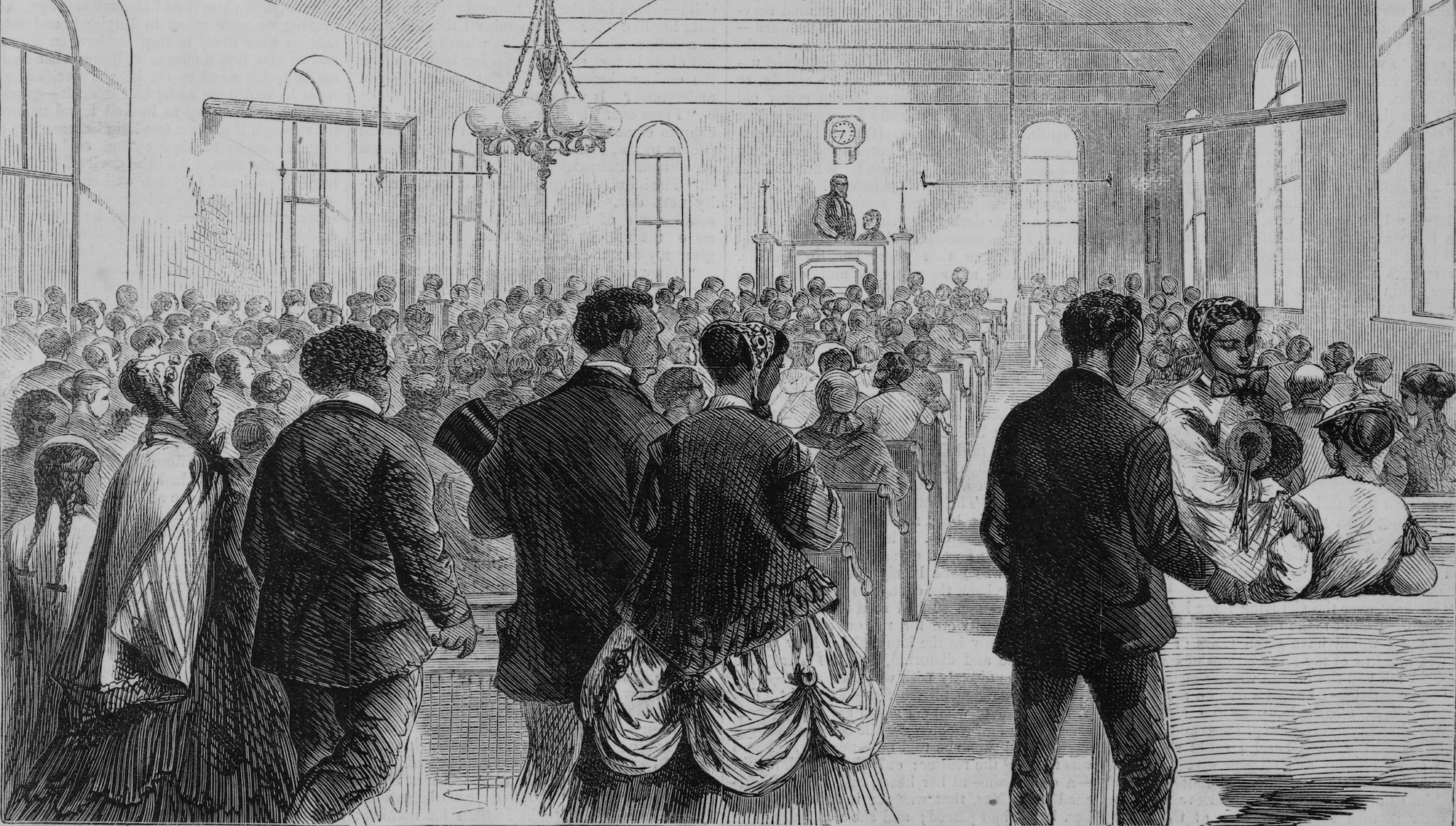

On Portsmouth material culture, and the social lives of enslaved, indentured, and free people in this town, see Mark J. Sammons and Valerie Cunningham, Black Portsmouth: Three Centuries of African-American Heritage (Lebanon: University of New Hampshire Press, 2004); Valerie Cunningham Papers, MC 321, University of New Hampshire Library, Milne Special Collections and Archives; Brock W. Jobe, Portsmouth Furniture: Masterworks from the New Hampshire Seacoast (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1993); Rick Russack, “Four Centuries of Portsmouth Furniture,” Portsmouth Historical Society, May 16, 2017.

Critical engagements with “campus collections” across New England, North America, and globally are wide and growing. Students, faculty, curators, and community members are doing essential interdisciplinary work to revisit, contextualize, and transform these spaces and practices. For a small sampling of initiatives just in the Northeast, at a range of private and public institutions, see Americas Research Initiative, Rhode Island School of Design Museum; “Dialogue with the Collection Program” and collaboration with Fred Wilson, University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts Amherst; The Lost Museum: The Jenks Museum of Natural History and Anthropology, Brown University; Dorothy Wang and Kevin Murphy, “Uncovering Williams” class and WMCA exhibition (2019); Sonnet Kekilia Coggins and Kailani Polzak, “‘The Field is The World’: Williams, Hawaiʻi, and Material Histories in the Making” (2018); Horace Ballard, Kevin M. Murphy, and Elizabeth Sandoval, “Remixing the Hall: WCMA’s Collection in Perpetual Transition”; Destinee Filmore, Jordan Horton, and Nicholas Liou, “Curatorial Close Looks: Remixing the Remix”; Lisa Conathan, Lori DuBois, Anne Peale, “Teaching with Primary Sources at Williams College” (2020); Places, Nations, Generations, Beings: 200 Years of Indigenous North American Art, Yale University Art Gallery (2019-2021); Christine DeLucia, “Fugitive Collections in New England Indian Country: Indigenous Material Culture and Early American History Making at Ezra Stiles’s Yale Museum,” William and Mary Quarterly 75 (Jan. 2018): 109-150; Ethan W. Lasser, ed., The Philosophy Chamber: Art and Science in Harvard’s Teaching Cabinet, 1766-1820 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017).

Communities and institutions are partnering in new ways, such as an innovative museum endeavor by the Tomaquag Museum in conjunction with the University of Rhode Island and RISD. Foundational ethical and human rights matters involving repatriation and restoration of belongings to communities remain major concerns at museums, despite important steps forward.

This article originally appeared in July, 2022.

Christine DeLucia is Associate Professor of History at Williams College and the author of Memory Lands: King Philip’s War and the Place of Violence in the Northeast (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018). Her work has appeared in The Journal of American History, The William and Mary Quarterly, Commonplace, Native American and Indigenous Studies, and other publications. She researches and teaches in areas including Native American and Indigenous Studies, early American history, material culture and museums, and community-engaged work.