The labor agitation guidelines set down at the inaugural 1834 National Trades’ Union Convention included a mandate that union members should “refuse honor and office to every man who does not promote by a good example and deeds of benevolence the welfare of his fellow beings.” Published in the September 6, 1834, issue of the official National Trades’ Union newspaper, such principles informed the audience (union members and potential members) of acceptable labor organizing behavior and provided some of the contours of an ideal worker identity. Within that same issue, the newspaper’s editors used the limited available space to publish a series of riddles under the title, “A Good Wife.” Noting what a “good wife ought to be like,” these riddles included that she should be, “like a town clock, keep time and regularity,” but should also, “not be like a town clock; speak so loud that all the town can hear.” While these riddles offer scholars an opportunity to probe contemporary humor for ideals of marital and gender relations, their inclusion in one of the nation’s first pro-labor newspapers also raises the question of the relationship between articles like “A Good Wife” that were seemingly separate from political economy content and more recognizably labor-related articles such as the proceedings of the National Trades’ Union Convention.

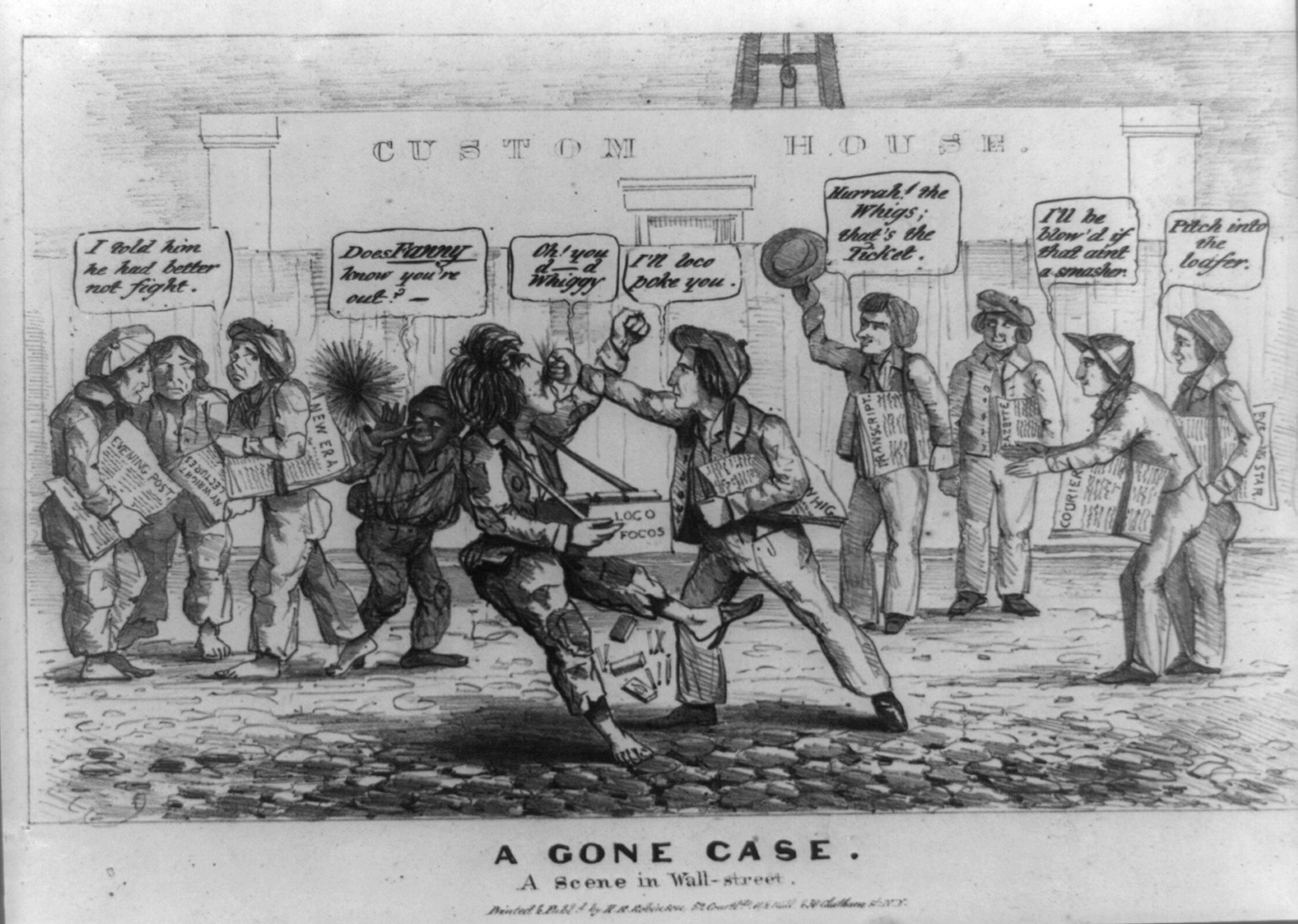

Reading papers like the National Trades’ Union, The Man, The Union, The Democrat, and the Working Man’s Advocate, New York City’s workers learned about the bank war, monopolies, Loco-Foco politics, and labor unrest. The editors of these newspapers: Ely Moore, George Henry Evans, John Commerford, and John Windt, read like a who’s who of 1830s New York labor activism, and eager readers clamored to hear their opinions. Alongside these articles however, each edition also contained what The Man referred to as “light-reading articles” such as poetry, marriage announcements, humorous aphorisms warning about abhorrent behavior, advertisements, and other news of the day. More than just filler clipped from out-of-town papers to pad the publication, these articles often appeared on the front page and usually occupied more than two full pages of a four-page newspaper. Journeymen readers expected anti-bank discussions to appear side-by-side with anecdotes about how artisans’ wives should act and did not see them as mutually exclusive. This analysis of pro-labor newspapers considers these articles and their importance to readers as a crucial aspect of the cultural lives of Jacksonian working men . . .

Like many light-reading articles, discussions of marriage often used humor to make a point. A report in the National Trades’ Union on July 25, 1835, from frontier Chicago noted that women were in demand and “some have thirty suitors at a time, and duels are not infrequent to obtain the prize of beauty: even old maids find a ready market, after a few shots.” Editors noted that they ran the article “by way of circulating the most important information; and hope those interested will profit by it.” This humor could also be used as a weapon of social criticism when the institution of marriage was not respected. The National Trades’ Union ran another story on May 2, 1835, entitled, “New way to get a husband,” that described a woman who tricked a lawyer into marriage. The older woman feigned illness and sent for the attorney to draw up her will. She exaggerated the sum of her estate and when she “thought proper to be again restored to health,” was visited by the lawyer who soon popped the question, only to later find out about her tiny estate. The lawyer, never a popular character in pro-labor papers, had been beaten at his own game in his attempt to marry for money . . .

Lawsuits for “Breach of Promise” were not just simple reminders that men should respect the institution of marriage; they were specifically punitive matters, reflecting the economic aspect of becoming a husband. The loss of a potential husband could mean economic devastation for a single woman and could not be forgiven by simple emotional excuses. At a time when average wages for skilled working men in New York City ranged from $1.00 to $2.00 a day, reported fines were often exorbitant and usually reflected the middle class background of the men involved in the cases. However, this type of light-reading article prescribed a certain set of guidelines for any man’s engagement. Their inclusion in a pro-labor newspaper localized the message for artisans and infused it into part of a masculine worker identity. One example of this genre from The Man on April 27, 1834, described a jury that “returned a verdict of 5,000 dollars for the plaintiff, the whole amount claimed in the declaration. Have a care, young men!” The heavy fines reflected that marriage as an economic contract under laws of coverture needed to be protected accordingly; artisan readers could identify with the message of masculine obligation even if the judgements clearly fell outside their financial purview . . .

Bachelors were also popular topics of conversation in 1830s New York City, from pro-labor newspapers to middle-class novels and health reports. This was not a new fear. Newspapers identified bachelors as dangerous and destabilizing members of New York society going back to the eighteenth century. It was an exaggeration that bachelors ran rampant and that marriage was under attack by rogues, but the threat certainly felt real when highlighted repeatedly in the press. Low marriage rates for working men in the city and the notion that certain men did not even want to participate in the institution flew in the face of the papers’ pro-marriage message. In The Man’s March 7, 1834, daily “Marriages” column, a notice even ran under a blank space, declaring, “If people won’t marry, we can’t help it.” . . .