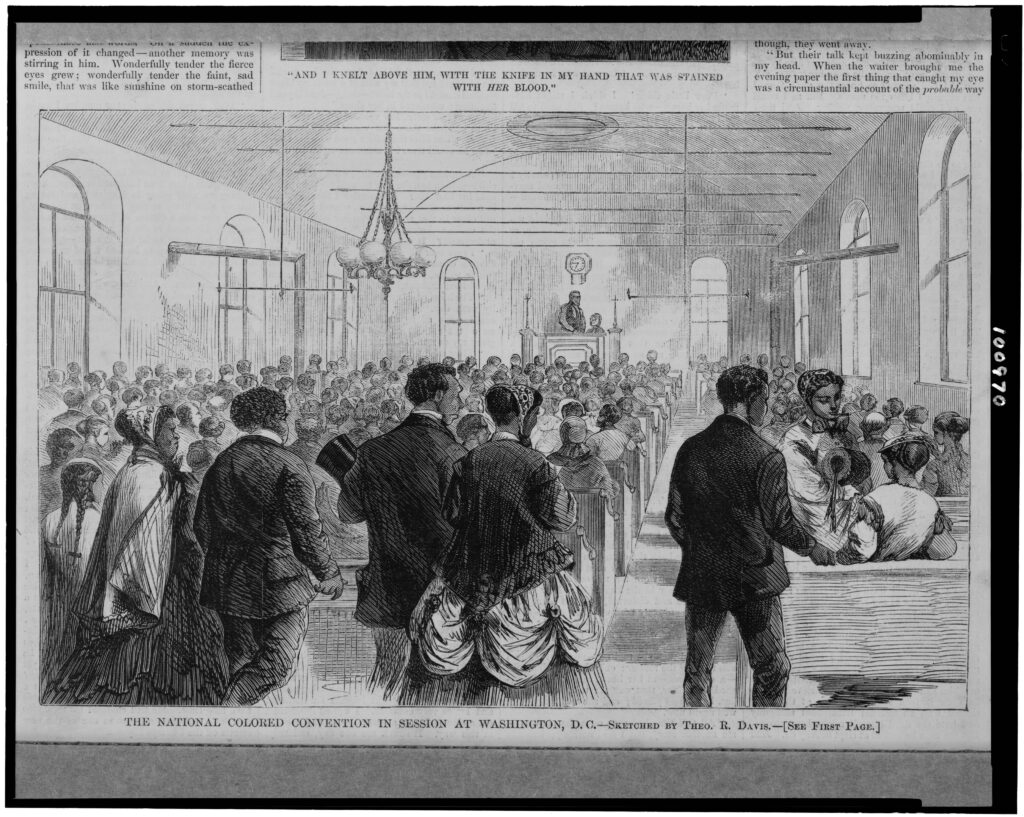

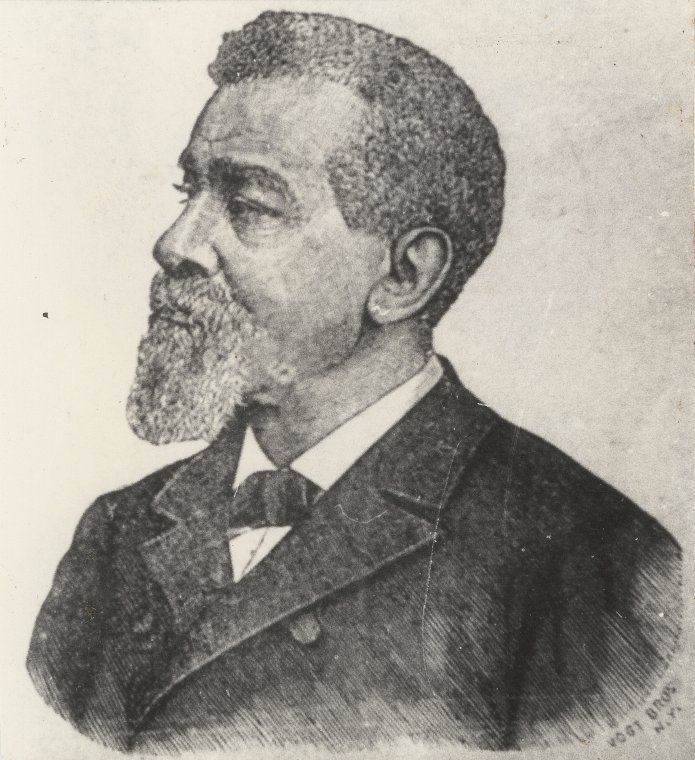

Speaking at the National Convention of the Colored Men of America in January 1869, the prominent Black reformer and businessman George T. Downing talked about an awakening of the “moral sense of the nation.” Downing urged the delegates to work to secure “some final measure of equal and universal suffrage, without any discrimination on the grounds of race, color, previous condition or of religious belief.” Reconstruction-era constitutional amendments had already abolished slavery and established national birthright citizenship. The far-reaching political and constitutional changes of the post-Civil War constituted a “second American Revolution,” according to the abolitionist William Goodell. For Downing and other reformers, adult manhood suffrage, regardless of race, was of paramount importance by the end of the 1860s.

Expanding the Boundaries of Reconstruction: Abolitionist Democracy from 1865-1919

Sinha also greatly enlarges the temporal boundaries students are accustomed to (1865 to 1877), by covering the end of the nineteenth century—including labor reform movements, the subjugation of Native American tribes in the West, and the rise of American imperialism—into the Progressive era with the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment.

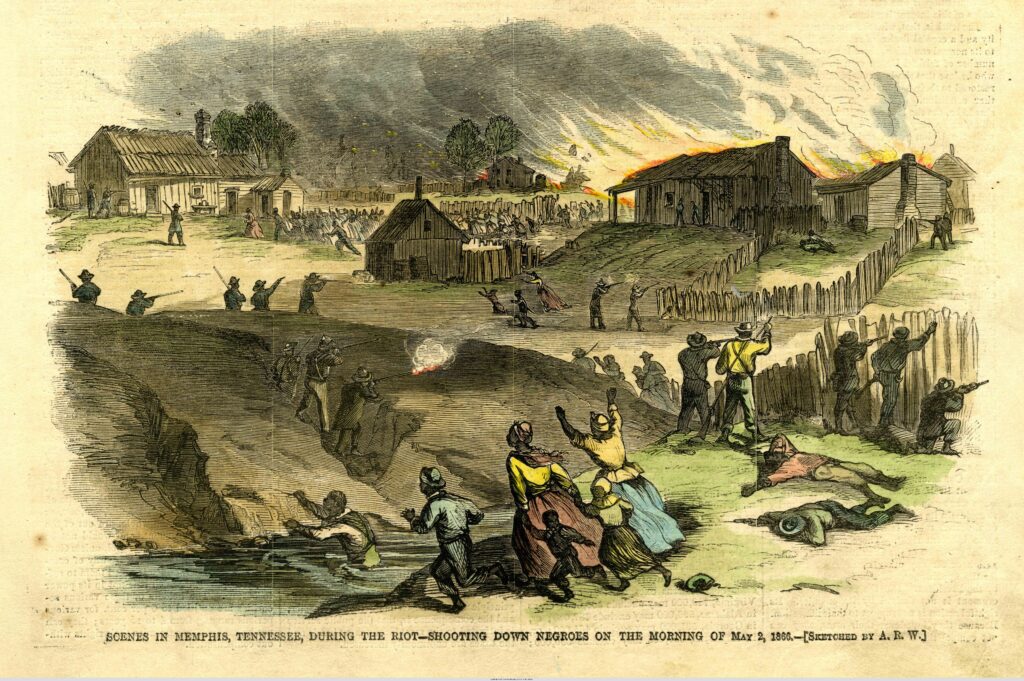

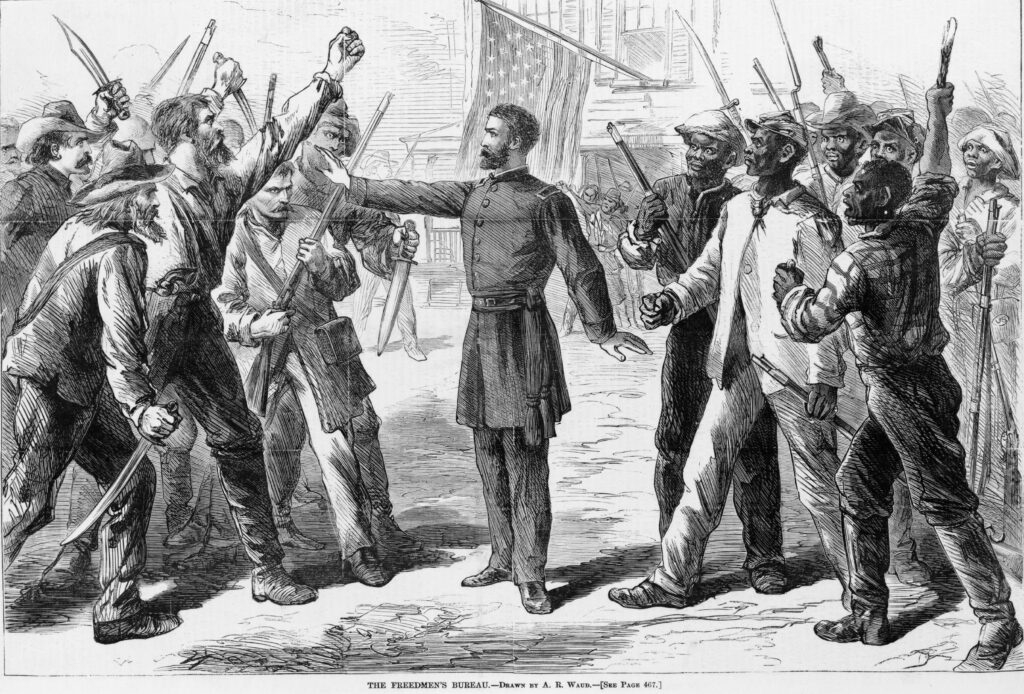

Downing understood how dangerous the “wilderness” was for Black Americans in the years after Appomattox. If the new republic was to be a biracial democracy it needed to be guided by a federal commitment to its most vulnerable citizens, especially in an era of unprecedented violence. The reign of terror in the South that followed the war was stark, with white vigilantes roaming through rural and metropolitan areas, disarming Black Union soldiers and threatening and killing community leaders. As W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in his classic work Black Reconstruction in America (1935), civil wars are “doubly difficult to stop,” for it becomes all the more likely that “war may go on more secretly, more spasmodically, and yet as truly as before the peace.”

Historian Manisha Sinha’s deeply researched account of the “fraught and contested” period of Reconstruction covers in detail the efforts of George Downing and other reformers to expand the scope of American democracy after the Civil War. Sinha also greatly enlarges the temporal boundaries students are accustomed to (1865 to 1877), by covering the end of the nineteenth century—including labor reform movements, the subjugation of Native American tribes in the West, and the rise of American imperialism—into the Progressive era with the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment. In Sinha’s engrossing work, Reconstruction is both a “transregional and transnational” story (309). Sinha moves beyond Eric Foner’s classic, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (published in 1988)—not necessarily disagreeing but broadening the definition of Reconstruction’s overthrow to go well into the twentieth century. Sinha, drawing from the influence of Foner who served as her graduate school advisor, considers the contested nature of American democracy by examining the fissures within the republic created by disputes over race, gender, citizenship, nation-state building, immigration, law, political economy, and empire. Sinha’s new work builds on the themes presented in her award-winning book The Slave’s Cause (2016).

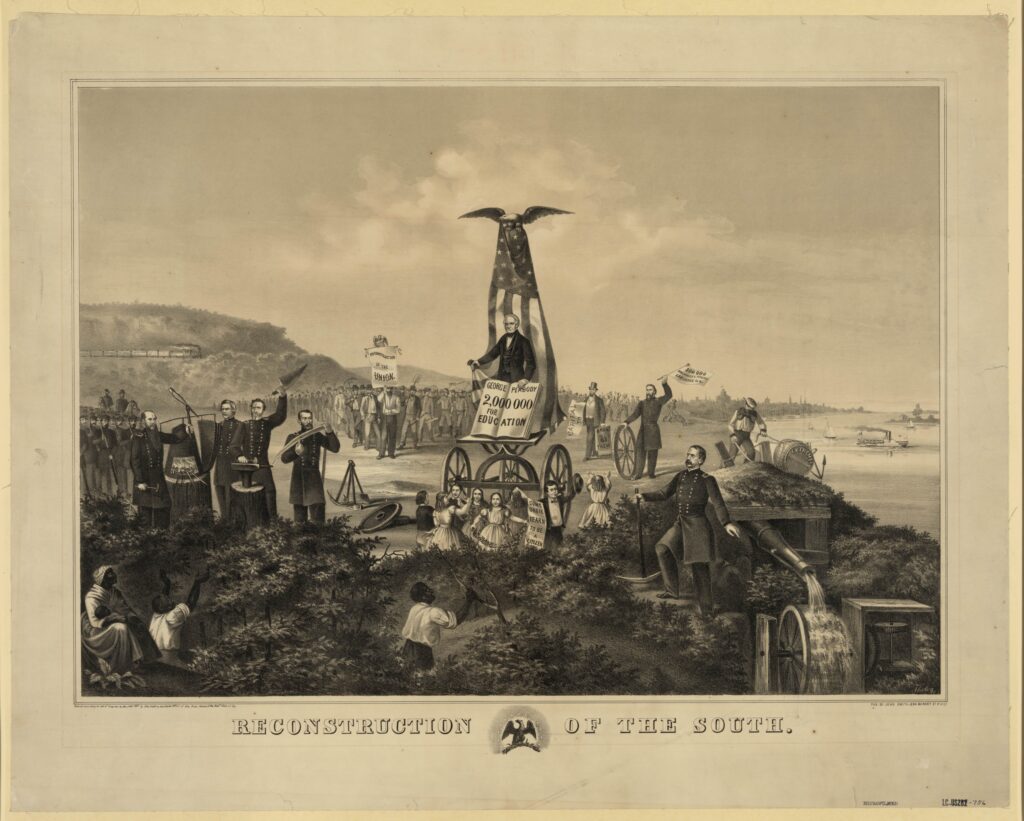

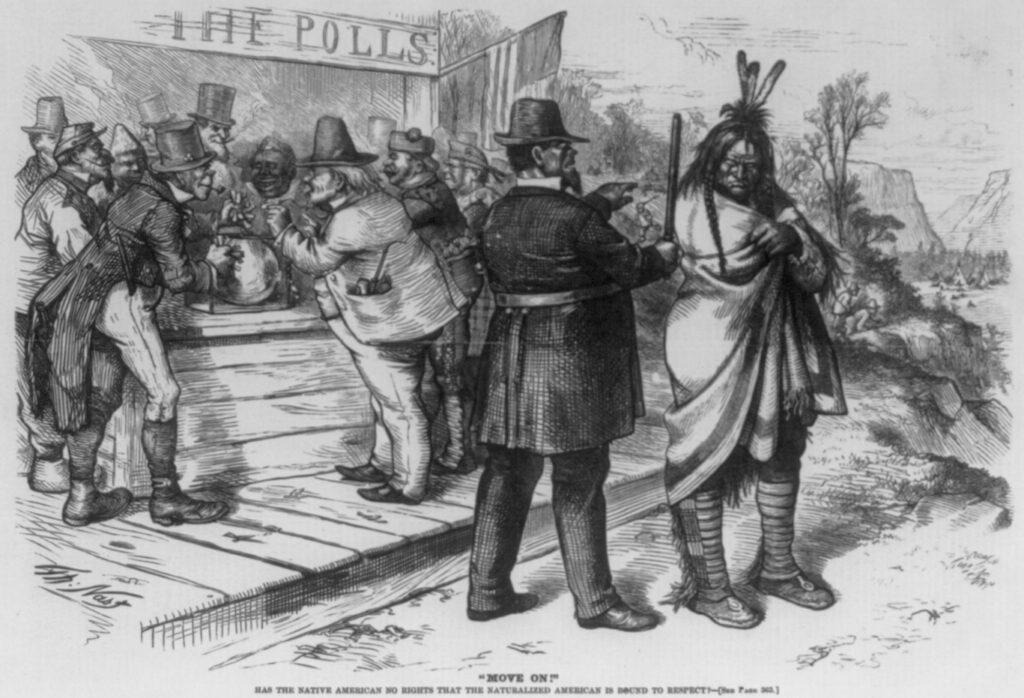

The Rise and Fall of the Second American Republic is engaging, elegantly written, provocative, and destined to become the new standard text on the period. Sinha’s approach allows her to tell a fast-paced story that is deeply informed by decades of research and teaching. Sinha’s grand narrative incorporates a deep reading of the secondary literature and a fresh examination of primary sources, in a similar vein to historian Nell Irvin Painter’s classic work, Standing at Armageddon: The United States, 1877-1919 (1987), succinctly capturing the political, social, and economic forces at play. Over the course of a dozen cogently written chapters, Sinha demonstrates how the U.S. military that battled against southern counterrevolutionaries was redeployed to the West to engage in the Indian Wars. Southern efforts to disenfranchise Black Americans were repackaged and deployed in the North to target immigrants and the industrial working-class. Of particular importance is Sinha’s treatment of the women’s suffrage movement. Sinha clearly demonstrates how the failures of Reconstruction led not just to the loss of an interracial democracy, but also delivered a crushing blow to the equal rights battle for women.

Sinha begins by weaving together several strands of the emancipation story usually treated separately: abolitionism, the story of liberated slaves and missionaries who worked with them, and accounts of slaves achieving their freedom in the tumult of war. Sinha chronicles how abolitionist reformers, Black and white, male and female, understood the meaning of the Civil War and fought for change after four years of brutal carnage came to an end in April 1865. As the abolitionist U.S. Senator Charles Sumner proclaimed in June 1865 to the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society: “Liberty has been won, the battle of Equality is still pending.”

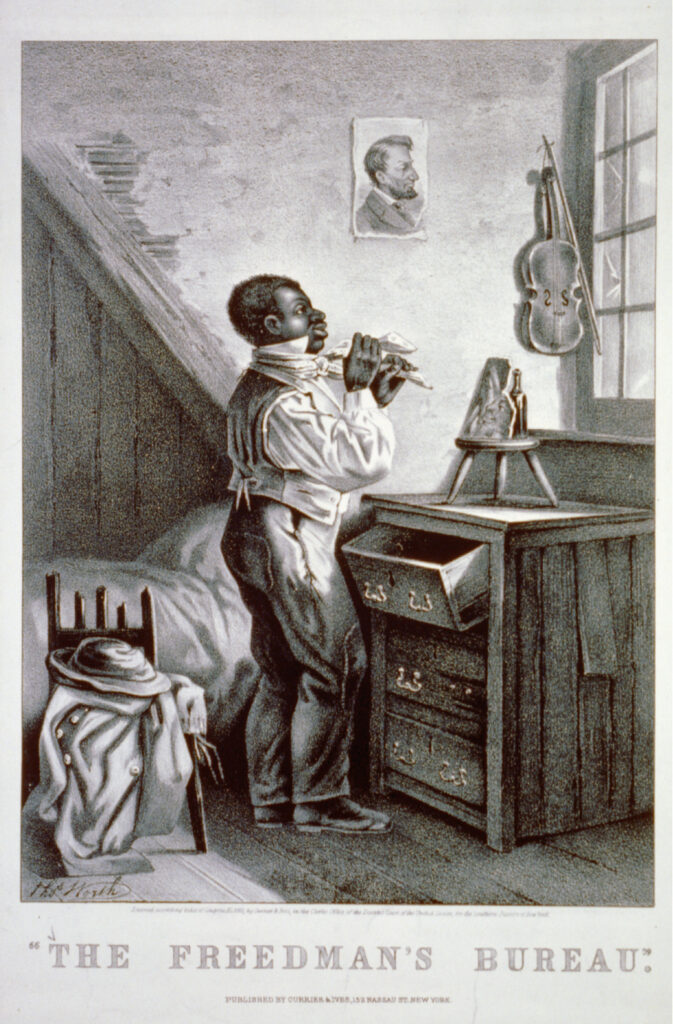

Building on Du Bois’ Black Reconstruction, Sinha uses the phrase “abolition democracy” to detail the new vision of democracy that radical Republicans and Black leaders came to embrace in the postwar period and into the twentieth century. For classroom teachers, the author’s discussion of what she calls “grassroots reconstruction”—the significance of a “range of actions by disenfranchised groups on the ground to expand the boundaries of national citizenship and belonging”—will serve to expand the curriculum in rich and meaningful ways. Sinha’s mining of Freedmen’s Bureau records offers readers a “glimpse into how freedpeople tried to deploy it in defense of themselves, their homes, families, and communities, even when confronted with racist or unsympathetic agents” (131). Sinha also details the impact of the Union Leagues and Republican clubs, along with Black conventions, and the actions of Black leaders at constitutional conventions in the South.

The “main concern of Reconstruction was the plight of the formerly enslaved, but its fall affected other groups as well, from women and workers to immigrants and Native Americans” (xvii). Sinha succeeds in her stated goal to put Reconstruction in a “broad transnational context” and to “demonstrate that its long death has as much to tell us as its short-lived triumph” in the 1860s and early 1870s (xix). Her coverage of the Lost Cause mythology clearly demonstrates how it was not just nostalgia for the old House of Dixie. Rather it became the ideological handmaiden of American imperial efforts, drawing strength from southern redeemer views and the concomitant anti-Native American ideology used to justify subjugation out West.

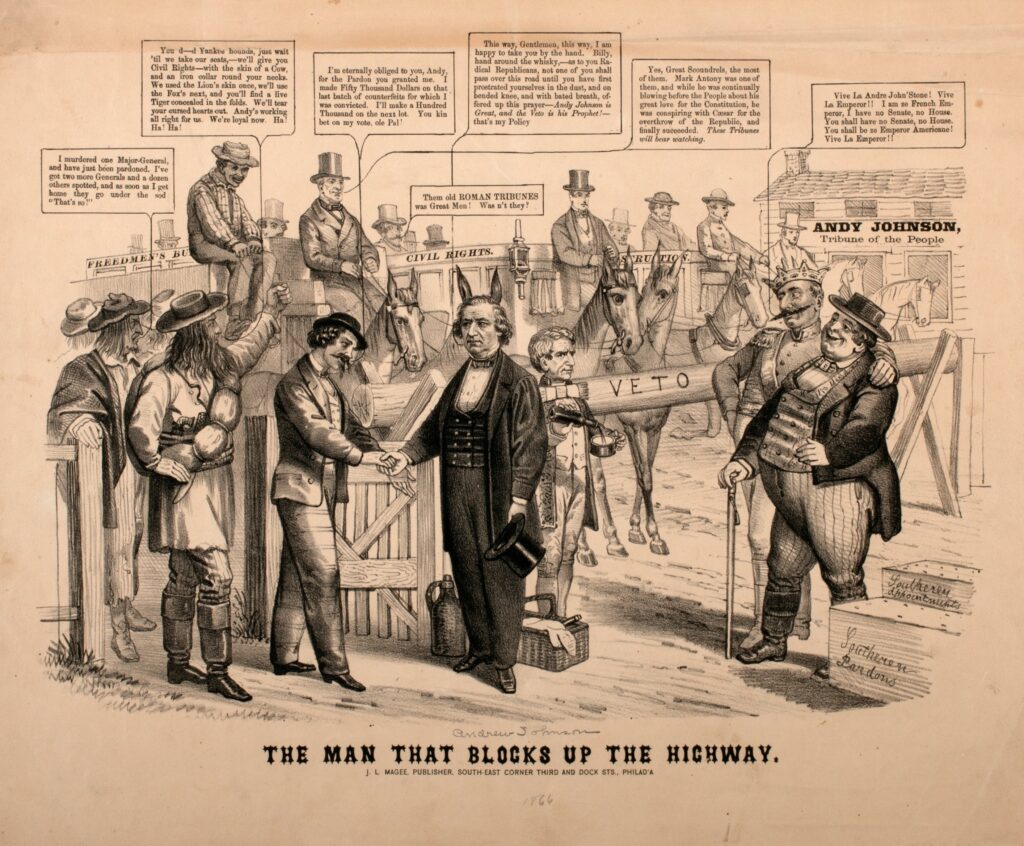

Sinha devotes considerable coverage to the movement for land redistribution at the end of the war to examine how the policies of Lincoln’s successor in office, Andrew Johnson, eventually led to an overthrow of the radical Republican agenda. Building on the research and themes presented in the work of historians, including but not limited to, Douglas Egerton’s The Wars of Reconstruction (2014), Gregory Down’s After Appomattox (2015), William Blair’s The Record of Murders and Outrages (2021), and Fergus Bordewich’s Klan War: Ulysses S. Grant and the Battle to Save Reconstruction (2023), Sinha chronicles how Reconstruction ultimately failed due to the use of violence, economic coercion, racist terror, and an unsympathetic U.S. Supreme Court. African Americans vigorously resisted Jim Crow and the application of a separate-but-equal doctrine. In Louisiana, Kentucky, Florida, Tennessee, Maryland, and Oklahoma, Blacks challenged separate coach laws. Under Jim Crow travel, Blacks could not move freely from one coach cart to another. Sinha demonstrates how late nineteenth-century Jim Crow statutes were not just part of southern exceptionalism, but rather became mainstream during the Progressive period and the ideology of regulation in the early twentieth century.

One omission in Sinha’s engrossing story is a deeper engagement with scholarship relating to reconstruction in the North. Hugh Davis’ important work, “We Will Be Satisfied With Nothing Less” (2011) tells the story of Black leaders and protests against inequality in education, public accommodations, and political life. Like Octavius Catto in Philadelphia, George Downing protested against segregated travel in the North. After being thrown off a railroad car in Washington, D.C. in 1869—an incident that caused Charles Sumner to bring it up on the floor of the Senate—an indignant Downing penned an editorial for the New-York Tribune, drawing on Roger Taney’s infamous ruling in the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford case for the title, “Have Black Men Any Rights that Railroad Conductors are Bound to Respect?” Downing maintained that “the day had gone by when railroad companies or other corporations can thus, through their agents, unnecessarily and brutally injure the feelings of a man . . . who is willing to pay his fare, simply because of his color; for he has not only a growing moral sentiment at his back, but the ballot in his hand, and he will not yield.” Another important part of the northern story of Reconstruction to consider is contained in Janette Thomas Greenwood’s First Fruits of Freedom: The Migration of Former Slaves and Their Search for Equality in Worcester, Massachusetts, 1862-1900 (2009).

Sinha addresses the push for women’s equality in two separate chapters, one focused on the traditional period of 1865 to 1877 and the second, “The Last Reconstruction Amendment,” covering the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment. The passage of the Nineteenth Amendment was, as Sinha notes, a milestone in the history of reconstruction of American democracy. Sinha rightly notes that the women’s rights movement had its genesis in the abolition movement. During the Civil War, women “became foot soldiers in the civilian arm of the federal government” under the auspices of the United States Sanitary Commission and army nurses (201). As historian Carol Faulkner notes in Women’s Radical Reconstruction (2003), the design, implementation, and administration of Reconstruction policy was pushed along by female activism. In 1863, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony founded the Women’s National Loyal League. In 1864, Black women formed an independent Ladies Union Association to aid the needs of wounded and sick Black soldiers. And immediately following the war, feminists “relaunched the women’s conventions,” which had grown in size in the antebellum period. Sinha provides a rigorous account of the dynamics during the postbellum period with its many developments, including an account of the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) and its “fight for universal suffrage for black people and for women,” along with the eventual split within the women’s suffrage movement into two wings over the wording of the Fifteenth Amendment. Unfortunately, the split into the American Woman Suffrage Association, under the leadership of Lucy Stone—a central character in Sinha’s work—and the National Woman Suffrage Association, under Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, led to a twenty-year schism. As Sinha argues, the “abandonment of abolitionist feminists’ dual commitment to racial and gender equality” had “long lasting consequences for the American women’s movement” (195). The “deployment of racist logic for women’s rights would find new adherents” in the late nineteenth century (226).

In a chapter entitled, “The Conquest of the West,” Sinha makes the case for how the processes connected with the “unraveling of southern Reconstruction” were intertwined with the “reconstruction of the West” (309). As she notes, it was the insurgency against Reconstruction policies led by southern Democrats that “mirrors the wars against the Indians” in the American west (330). The “waning of Reconstruction” also “set the stage for the final campaign in the brutal subjugation of the indigenous nations,” as the U.S. “diverted the energies” from “emancipation to empire” (308). Building on the work of historian Heather Cox Richardson, Sinha carries her story of the West to the 1890 Wounded Knee massacre of the Lakota Sioux. Teachers will benefit from Sinha’s extended discussion of how abolitionist views of the Indian Wars and the construction of reservations, along with global imperial efforts at the end of the nineteenth century, were shaped by the struggle for Black citizenship. These same forces also led to the counterrevolution against the Republican use of active federal intervention in the economy, paving the way for a laissez-faire conception of the economic order.

Manisha Sinha’s grand narrative will become a staple for high school and college educators. Despite the proliferation of scholarship on Reconstruction over the last thirty years, an understanding of the definition of citizenship, the meaning of equality, the relative powers of the national and state governments—all major Reconstruction issues discussed by Sinha—continue to be lacking. If The Rise and Fall of the Second American Revolution achieves the readership it deserves, this problem will be rectified. Moreover, students will have a deeper understanding of important questions of citizenship, national belonging, and the role of the state in our fractured twenty-first century political world. Indeed, The Rise and Fall of the Second American Republic shows how Reconstruction and its legacies “continue to shape the contours of our democracy” (153). As George T. Downing deeply believed, America existed to “work out in perfection the realization of a great principle, the fraternal unity of man.” America’s “mission,” according to Downing, was ordained by God to create a “composite” nation, the “tendency was to blend different virtues and powers” into one civilization. In an 1881 speech at Harvard, the stalwart reformer Wendell Phillips, preached the necessity of “education” for America to keep functioning as a democratic nation. Manisha Sinha’s scholarship will help in this process.

Further Reading

William A. Blair, The Record of Murders and Outrages: Racial Violence and the Fight Over Truth at the Dawn of Reconstruction (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021).

David Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001).

Fergus M. Bordewich, Klan War: Ulysses S. Grant and the Battle to Save Reconstruction (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2023).

Hugh Davis, “We Will Be Satisfied With Nothing Less”: The African American Struggle for Equal Rights in the North During Reconstruction (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011).

Gregory P. Downs, After Appomattox: Military Occupation and the Ends of War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015).

W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880 (New York: Russell & Russell, 1935).

Douglas R. Egerton, The Wars of Reconstruction: The Brief, Violent History of America’s Most Progressive Era (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2014).

Carol Faulkner, Women’s Radical Reconstruction: The Freedmen’s Aid Movement (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003).

Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (New York: Harper Collins, 1988).

Eric Foner, The Secret Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution (New York: W.W. Norton, 2019).

Janette Thomas Greenwood, First Fruits of Freedom: The Migration of Former Slaves and Their Search for Equality in Worcester, Massachusetts, 1862-1900 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

Caroline Janney, Ends of War: The Unfinished Fight of Lee’s Army After Appomattox (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021).

James McPherson, The Struggle for Equality: Abolitionists and the Negro in the Civil War and Reconstruction (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1964).

Nell Irvin Painter, Standing at Armageddon: The United States, 1877-1919 (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1987).

Heather Cox Richardson, Wounded Knee: Party Politics and the Road to an American Massacre (New York: Basic Books, 2010).

Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016).

This article originally appeared in July 2024.

Historians Erik J. Chaput, Ph.D., and Russell J. DeSimone are the co-creators of the award-winning Dorr Rebellion Project website hosted by Providence College. Chaput teaches American history at Western Reserve Academy. They are the authors of numerous articles on early American history, including “George T. Downing and the ‘Fraternal Unity of Man’: The Battle for an Abolition Democracy in Nineteenth-Century America” (Newport History, Summer 2024). In January 2025, their edition of the Selected Writings of Thomas Wilson Dorr will be published by the Rhode Island Publications Society. They are currently at work on a biography of George T. Downing.