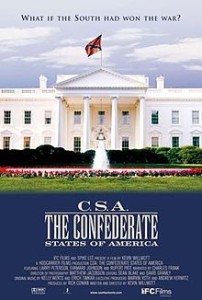

The question of what might have transpired should the Confederacy have triumphed during the Civil War has been and remains one of the most common exercises in American historical fantasy. And, as director Kevin Willmott proves in this amusing and scathing “documentary,” the question endures for good reason.

Clearly inspired/frustrated by Ken Burns’s ubiquitous (and romanticized) PBS series The Civil War, Willmott sets himself an ambitious agenda—to claim slavery as the essential story of the Civil War, to mock the American fascination with historical documentary, and to remind the viewer that American racism has proved to be an enduring phenomenon. Little wonder, then, that the movie opens with a line from George Bernard Shaw: “If you’re going to tell people the truth, you better make them laugh; otherwise they’ll kill you.” To Willmott’s credit, the film is funny. Presented as a faux British documentary about the Confederate States of America deemed too “controversial” to show to the American public until now, the film presents the Confederacy as the victors of the Civil War and reimagines subsequent historical events in that light. There is also a loose plot about the influence of the fictional Virginia political dynasty of the Fauntroys, whose scions—John Ambrose Fauntroy I-V (no doubt a winking reference to Little Lord Fauntleroy)—are depicted as the arch-defenders of American slavery. But with the exception of the film’s conclusion, the plot operates as an afte rthought to the chief purpose of the work, which is to explore the intertwined legacy of the Civil War, American racism, and the institution of slavery.

rthought to the chief purpose of the work, which is to explore the intertwined legacy of the Civil War, American racism, and the institution of slavery.

Targeting an audience well-versed in history, the movie’s main gag is to present many famil iar touchstones of American history and culture as if seen in a mirror. Instead of crushing defeat, the Confederacy, thanks to timely British and French intervention, routed the Union army at Gettysburg and forced Ulysses S. Grant to surrender to Robert E. Lee, thus preserving the institution of American slavery for all eternity. Although these recurring counterfactual jokes become repetitive and predictable, they are for the most part quite clever. Gone with the Wind is replaced by A Northern Wind; I Married a Communist becomes I Married an Abolitionist; and The Blue and the Gray naturally transposes to The Gray and Blue. Seeing “CSA” on the side of rockets launching into space and the Confederate battle flag planted on the moon does get silly. But there is valuable insight in these parodies, which reveal core truths about American history that often go unnoticed in popular culture. The most penetrating bit of inversion comes from the treatment of Abraham Lincoln, who replaces the downtrodden Davis as the symbol of ultimate defeat. According to the movie, following the Confederate capture of Washington, D.C., Lincoln fled toward Canada, disguised not as a woman but in blackface, only to be apprehended. The arrest becomes the keynote scene in D.W. Griffith’s 1915 classic movie, The Hunt for Dishonest Abe (replacing, of course, Birth of a Nation). Although eventually released from prison despite his conviction for war crimes, in bitter exile in Canada, where he died in 1905, Lincoln admits late in life that Union defeat was the result of his and the North’s using the issue of race as a cudgel against the South, but never being sincerely committed to true freedom for African Americans. How untrue is this statement in reality? The irony here is that the northern commitment to racial equality proved tenuous at best. This moment is satire in its highest form—pointing out that in the end the Union and Confederacy were both beholden to racist ideologies, and that they shared more in common than we often care to admit.

Not all the humor works as well as the section on Lincoln, as the momentum of the story drags during the creation of a “Tropical Empire” in South America, and with the retelling of the Confederacy’s strong relationship with Adolf Hitler. By the time the viewer arrives in the recent past, jokes about the Slave Shopping Network are likely to be shrugged off. Perhaps sensing this, Willmott wisely uses another tactic to keep the audience engaged. Interspersed throughout the film are commercial interludes for products ranging from Confederate Family Insurance to the drug Contrari—a pill to break the will of resistant slaves. While many of these advertisements are fictional, there are several actual products that were commonly sold in nineteenth- and twentieth-century America. The point is clear—that the prevalence of American racism remains so powerful that the line between the absurd and the real can be difficult to perceive.

Although the film does effectively elicit laughs and outrage, its overall impact is less than the sum of its parts. The low-budget origins and look of the movie date the effort—although anyone familiar with documentaries might argue that this only enhances its credibility. And at almost an hour and a half it runs a bit long to be of use in most college classrooms, where ideas such as these could spark worthwhile discussion. But the biggest concern ironically derives from the strength of Willmott’s understanding of the nature of American racism as perhaps the central theme of all our history, North and South. Though his use of satire about the topic of slavery is often perceptive and sometimes funny, who will want to laugh alongside him? One suspects that the only people watching CSA are already in agreement. This is to say that a more nuanced presentation—one that acknowledges that in many ways, and at least for many years, the South did win the Civil War when it came to the subject of race, largely because racism was never a purely southern phenomenon—would make for a more enduring film. Though the racial consequences of the Union’s victory were long in coming, given the persistence of institutional racism throughout Reconstruction, the Jim Crow era, and the continuing struggle for racial equality, the less believable satire of the second half of the movie reveals that the momentous first steps of these effects would be impossible without—and irreversible with—the Union’s victory. As a clever novelty act, CSA is a success, but it turns out that there are limitations to any genre, whether parody or documentary, and that no matter how enticing historical fantasy may be, it rarely matches our appetite, and our need, for the real thing.

This article originally appeared in issue 13.4.5 (September, 2013).

Benjamin Cloyd is an instructor of history and the Honors Program director at Hinds Community College in Raymond, Mississippi. He is the author of Haunted by Atrocity: Civil War Prisons in American Memory (2010).