When I was growing up, the history of my ancestors’ involvement with Native Americans had been almost completely obliterated from my family’s memory. I assumed that my forebears bore no direct responsibility for the transformation of indigenous inhabitants into despised outsiders in their own land. I thought my ancestors had come to North America in the 1840s during the Irish potato famine and that the dirty work of dispossession and colonization had been accomplished long before. Yet I felt an amorphous sense of guilt towards native people, which I sensed many others shared, but which was never talked about.

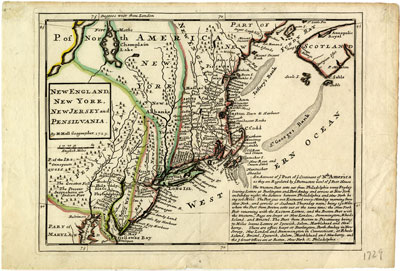

Over the course of my research for Distant Relations, I learned that some branches of my family had in fact arrived in New England in the 1630s, and that, far from being a single event in the past, colonization and dispossession were processes in which my family had been involved for many generations, through wars, diplomacy, dubious land transactions, and missionary activities. In the seventeenth century, for example, Thomas Stanton, my ancestor of ten generations’ remove, was directly involved in the attempted genocide of the Pequots and in the Atherton Company’s land scam to dispossess the Narragansetts; in the eighteenth century, my Ranney and Janes ancestors moved onto unceded land in Vermont; in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, my Harris and Freeman relations were busy trying to “civilize” and Christianize the Ojibwa in Ontario. As a descendant of these colonizers, the question of responsibility became very personal.

It was easy to attribute ignorance to my forbears or say that they were simply sharing the attitudes of the day, but it was much harder for me to acknowledge the self-interest in their blindness. They stood to profit if they didn’t recognize the full humanity of indigenous peoples. Unfortunately, this dynamic is still true today—for me and for other non-native North Americans.

Do I feel guilty? Once I began to understand the context for my ancestors’ actions, what I felt was not so much guilt as grief. I needed to mourn the human cost of it all, the collective losses that came from my ancestors’ shortsighted self-interest and lack of understanding of other cultures. I also came to see that colonization and dispossession were not the work of a few “bad” or misguided leaders, but rather were processes involving choices and actions by countless ordinary people—the “good” well-meaning people like my socially progressive grandfather who was involved in an Indian residential school in Ontario, as well as those who were greedy and selfish or simply hated Indians. Most of my ancestors were acting within the norms of their culture, but within the norms of a culture, decent people can do indecent things.

“I don’t see myself as personally responsible for the actions of my predecessors, but I recognize that I have inherited their legacy.”

I don’t see myself as personally responsible for the actions of my predecessors, but I recognize that I have inherited their legacy. Because my family has been involved in the oppression of aboriginal people for hundreds of years (whatever the intentions of individual family members), and because this oppression still continues—and because I continue to benefit personally from this oppression—I feel a responsibility to address the wrong that has been done. I believe it is the responsibility of nonnative North Americans to actively change the relationship between our peoples, and to return to Native Americans the resources and power needed to live their lives on their own terms. As Ojibwa playwright Drew Hayden Taylor said, “I don’t expect you to feel guilty for what your ancestors have done. However, if things haven’t changed in twenty years, then I expect you to feel guilty!”

The issue of responsibility is therefore not limited to people like me who have a blood relationship to the early colonizers. All nonnatives are the beneficiaries of the colonizing process initiated in the early 1600s. All who came here willingly or whose ancestors came here willingly are descendants of the early settlers in this sense; they have inherited their material and cultural legacy and are now enmeshed in a colonial relationship with the continent’s first peoples.

Indeed, much as we might wish it were otherwise, “colonization” is not over, either for the colonized or the colonizers. Whether I like it or not, my house in Toronto sits on land that was acquired by the British Crown under questionable circumstances in the 1790s, and that is now subject to a land claim by the Mississaugas of New Credit. Even recent immigrants become implicated because they too partake of the benefits of past injustices. Many aspects of colonialism—the inadequate land and resource base left to Native Americans, the imposition of foreign systems of government, the lack of recognition of the native right to self-determination—persist. Colonialism’s two key assumptions—that Native Americans have fewer rights to their land because they do not use it as Euro-Americans do, and that they need Euro-American direction to live their lives—are still very much with us today.

So what can we do? I believe we have a collective responsibility to unsettle the settler stories that are usually taught in schools, related in local histories, or passed down in families. Too often, these settler narratives are essentially creation myths—highly selective accounts of national or familial origins that are meant to instill pride and a sense of purpose. The stories most children learn speak of “settlers” and discovery and Puritan forefathers; they obliterate or minimize the ways that the Europeans pushed out the original people of this land. Let’s be honest about what our people did: not just the political leaders or the government or the army, but also what ordinary settlers did or condoned.

Unfortunately, history is full of examples of nations lying to themselves about how they have treated certain groups and creating a deformed national identity as a result. By and large, we avoid facing the fact that our effect on aboriginal people has been catastrophic. We do not want to acknowledge our relationship to desperate poverty, internalized racism, and epidemics of teenage suicide. Such knowledge disrupts not only our understanding of ourselves but our sense of the very legitimacy of the Canadian and American states. Avoiding the truth is a lot easier, precisely because acknowledging wrongdoing brings up the question of responsibility.

Certainly, in Canada at least, many school teachers and even some historians still erase native history from the general history of the country, or relegate that history to a sidebar to the main story. But to ignore the fact that relations between indigenous and nonindigenous peoples are a foundational and continuing dynamic in both Canadian and American history is to participate, however unwittingly, in the process of cultural genocide—the destruction of a people through the obliteration of their history and identity. Recognizing the mere presence of Native Americans in “our” history is not sufficient; we need to incorporate contemporary Abenaki, Mohegan, Narragansett, and Pequot perspectives and interpretations into a shared history of New England, for example, giving up our role as exclusive arbiters of what that history is.

One thing I’ve learned from indigenous peoples is that history is alive. The stories we tell, especially those about where we come from, no matter how heavily footnoted they are, carry “spirit” from one generation to the next—the spirit of a people, of a family, or just of vibrant life. There can be “good medicine” in stories, especially when they don’t shy away from complex truths. Our history, like other forms of story, has a potential for healing, for restoration, for clues as to how to right this very wronged relationship between our peoples.

In my view, such education and truth telling are the necessary preconditions for our other responsibility: effective action. Transforming a relationship from one based on domination to one characterized by balance, fairness, and mutual respect is a huge challenge. Yet, if colonization has been the product of the attitudes and actions of millions of people, it can also be undone through many small changes and actions. Each one of us in North America is part of this relationship and can do something to make it right. Further Reading: See Erna Paris, Long Shadows: Truth, Lies and History (New York, 2001); and Drew Hayden Taylor, “Reflections on the White Man’s Burden,” Toronto Star, October 7, 1998, sec. A, p. 27. See also Sylvia Van Kirk, “Competing Visions: Integrating Aboriginal/Non-Aboriginal Relations into Canadian History,” at “Turning Point: Native Peoples and Newcomers On-Line.”

This article originally appeared in issue 3.1 (October, 2002).

Common-place asks Victoria Freeman, author of Distant Relations: How My Ancestors Colonized North America (South Royalton, Vt., forthcoming November 2002), what kinds of responsibility do descendants of dispossessors have to history and to native peoples today?