Wendy A. Woloson’s In Hock (2009) traces the history of pawning in the United States from the eighteenth through the twentieth centuries, illuminating the strategies of poor and not-so-poor people as they grappled with economic hardship. Common-place asked her: can the struggles of working people during the great expansion of capitalism in the United States suggest any lessons for Americans today in devising strategies to deal with unemployment, poverty, and inequality? Or is our situation today decisively different from that faced by Americans in the early republic?

Soon after the Bernie Madoff scandal broke in late 2008, the major media outlets ran stories reporting that his former clients, now worth fractions of their former (imagined) wealth, were pawning unusually high-end collateral to pay their bills. A Palm Beach, Florida, pawnbroker, lending money on Hermès purses, Armani jackets, Tiffany rings, and $500,000 yachts, remarked that he was barely able to manage the uptick in business. For this brief, exceptional moment, pawnbroking had gone mainstream: struggling Americans, facing their own financial crises, could find some comfort in the tarnished collateral and faded glory of the rich becoming a little poorer.

Soon after the Bernie Madoff scandal broke in late 2008, the major media outlets ran stories reporting that his former clients, now worth fractions of their former (imagined) wealth, were pawning unusually high-end collateral to pay their bills. A Palm Beach, Florida, pawnbroker, lending money on Hermès purses, Armani jackets, Tiffany rings, and $500,000 yachts, remarked that he was barely able to manage the uptick in business. For this brief, exceptional moment, pawnbroking had gone mainstream: struggling Americans, facing their own financial crises, could find some comfort in the tarnished collateral and faded glory of the rich becoming a little poorer.

By contrast are the countless numbers of ordinary people with mundane goods (iPods and engagement rings, laptops and digital cameras) who transact business every day in pawnshops around the country. Their stories, all too familiar, rarely merit feature stories in newspaper and radio pieces. Today’s pawners engage in a practice that is centuries old, has changed little over time, and continues to play an essential role in people’s lives, whether rich or poor. Relatively simple, pawning is the process of using small pieces of “moveable” property (pawns) as collateral to secure a loan. Anything you can physically take to the pawnbroker, except living things and perishable articles, can be used to get a loan. What the pawnbroker lends is a fraction of the collateral’s actual value. To redeem your collateral you repay the loan with interest within a specified amount of time (usually a few months). If you fail to repay the loan within the allotted time, your collateral is unredeemed—forfeited to the pawnbroker, who is then free to resell it in order to recoup the amount he loaned to you and, ideally, to make a profit on top of that.

Today’s pawners engage in a practice that is centuries old, has changed little over time, and continues to play an essential role in people’s lives, whether rich or poor.

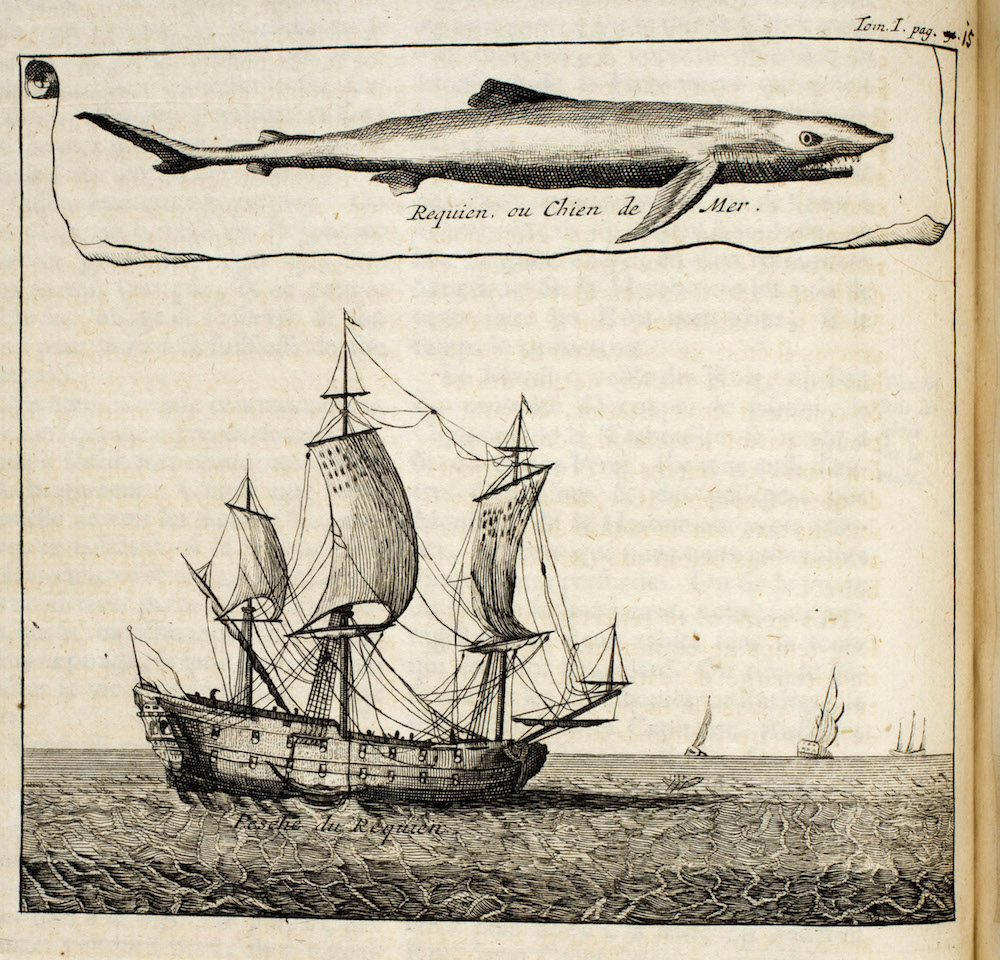

This basic process was also followed by Americans of the past, as far back as the early nineteenth century, when professional pawnbrokers first established their businesses in the country’s major cities along the east coast. Before urbanization and the rise of a capitalist economy, however, there was little need for a distinct pawnbroking profession. Because hard currency was in chronically short supply, it was common for Americans living in small, tightly knit communities to act as informal lenders to one another. Neighbors would often use farm animals or equipment as collateral to borrow money, especially when taxes came due and had to be paid with specie (gold and silver coins). Because they came into frequent contact with people on the move who were carrying personal property, tavern and innkeepers, too, often acted as informal pawnbrokers, accepting goods in exchange for a night’s lodging, food and drinks, or as security for a cash loan.

Before the 1830s, credit was in short supply to everyone but the well-off, who enjoyed the privileges of extended commercial networks based on social and familial connections. These men borrowed extensively from one another and in fact conducted much of their business wholly on credit. They also availed themselves of professional brokers who, distinct from pawnbrokers, offered financial services to entrepreneurs. These brokers performed a range of services for the elite, whose business needs were variable depending on the time and circumstance. Well connected and highly skilled in commercial matters, early brokers sold goods on commission; assembled captains, crews, and vessels for trading voyages; put investors in touch with each other; and loaned money, all “with the greatest dispatch, integrity, and secrecy,” according to one contemporary newspaper notice from 1770.

As the eighteenth turned to the nineteenth century, successful merchants and businessmen continued to share in and profit from the broad credit networks that helped them further their financial interests. Needing access to credit themselves, the poor and the middling, however, did not enjoy the same privileged membership in these exclusive circles and were left to their own devices. Turning to banks might have been an option were it not for the fact that banks at this time did not lend depositors money. Not established until the 1810s, the handful of existing savings banks were designed as repositories for extra earnings, to be drawn on only in exceptional circumstances, to pay for medical or funeral services. Bank organizers wanted their institutions to be didactic, to teach working people how to manage their money guided by people who were, they claimed, more responsible and respectable. That is, the elite.

In today’s moralizing critiques of people who have lost their homes to foreclosure or who have filed for bankruptcy, we hear echoes of the past. Then (as now), popular and financial commentators alike claimed that most Americans had neither the wits nor the self-control to manage their money and needed someone else to do it for them. Officers of the Bank for Savings of the City of New York (est. 1819), for example, blamed workers’ indebtedness on overspending, on “vanity” and the “desire of accumulation.” And organizers of Boston’s Provident Institution for Savings (est. 1816) argued that if people did not put their money away in savings accounts it “would be spent in fine clothes, or useless amusements.” Despite the current deteriorating financial prospects for many, judgments of people’s profligacy continue to be leveled against many Americans who struggle to make ends meet by maxing out credit cards and defaulting on car and home loans.

These attitudes have their roots in the first and second decades of the nineteenth century, when we begin to see the emergence of pawnbrokers as a distinct profession in urban areas. It is no coincidence that as capitalism became more fully formed in American cities, so, too, did pawnbroking. In fact, the two institutions went hand in hand: with the emergence of capitalism came the emergence of pawnbroking, and, in effect, the birth of the nation’s poverty industry. (Today’s poverty industry, it should be noted, is much more diverse and includes check-cashing outlets, tax preparation services, pre-paid phone cards, and rent-to-own stores).

The profound economic, demographic, and cultural shifts occurring in the first decades of the nineteenth century spurred the rise of capitalism, the growth of an underclass, and the spread of pawnshops. Immigrants from foreign countries and rural areas flooded east coast cities in search of employment and better lives. As manufacturers wrested control of production from European countries and consolidated their power, the organizational structure of large manufactories necessarily deskilled and disempowered formerly skilled and independent artisans. Additionally, a constant pool of unemployed laborers created a labor reserve that enabled industrial capitalists to pay as little as they could get away with, enlarging the class of working poor who became frequent pawnshop customers.

Pawnbrokers extended loans that ranged from a few weeks to a few months, that were typically for small amounts of money no more than a few dollars, and that people could get on the spot. By obtaining small, short-term loans immediately, pawners were able to supplement their insufficient wages, and in this way pawnbrokers played an essential role in supporting the development of industrial capitalism. They provided a much-needed form of credit that was unavailable anywhere else, including the banks.

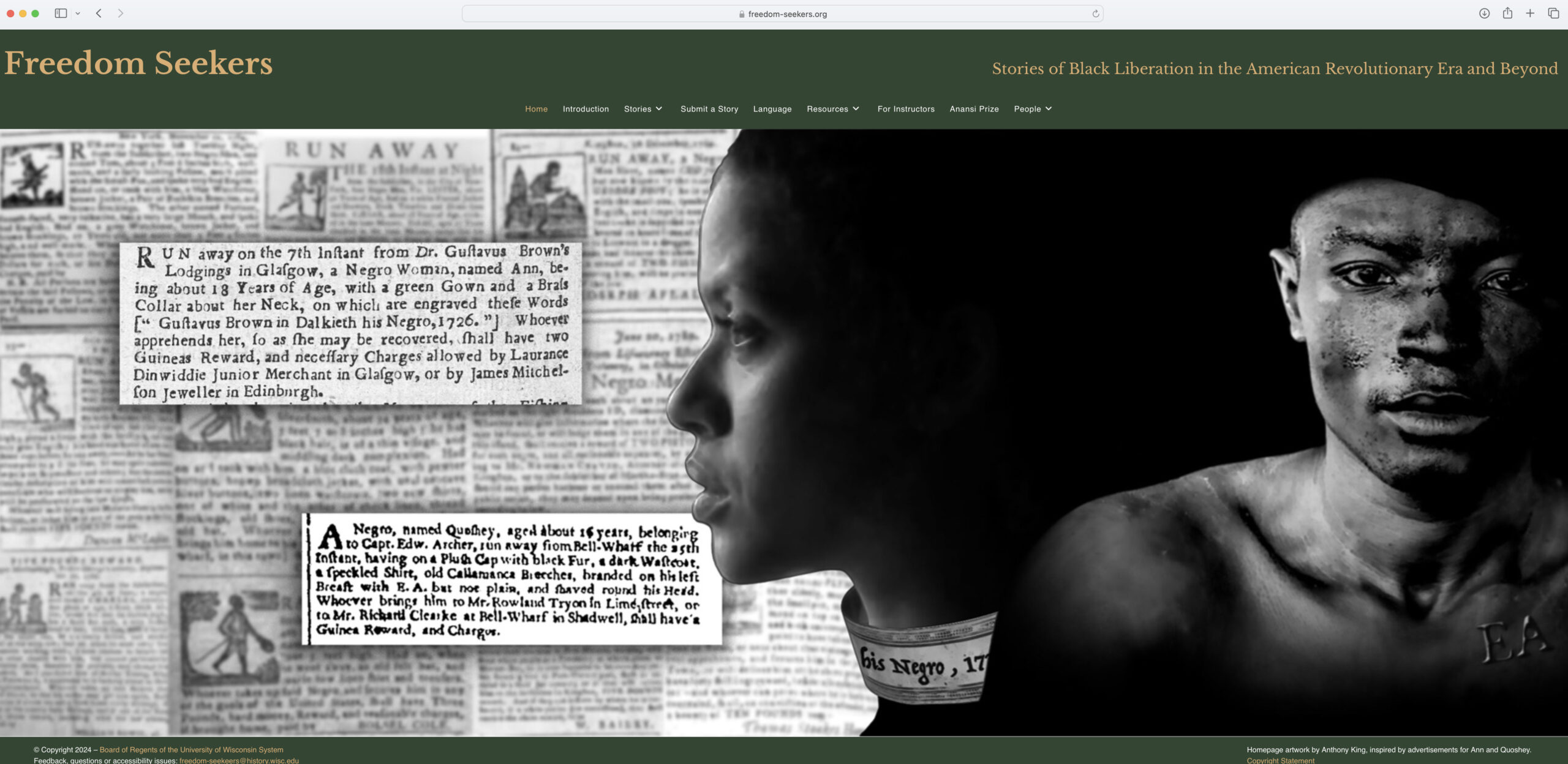

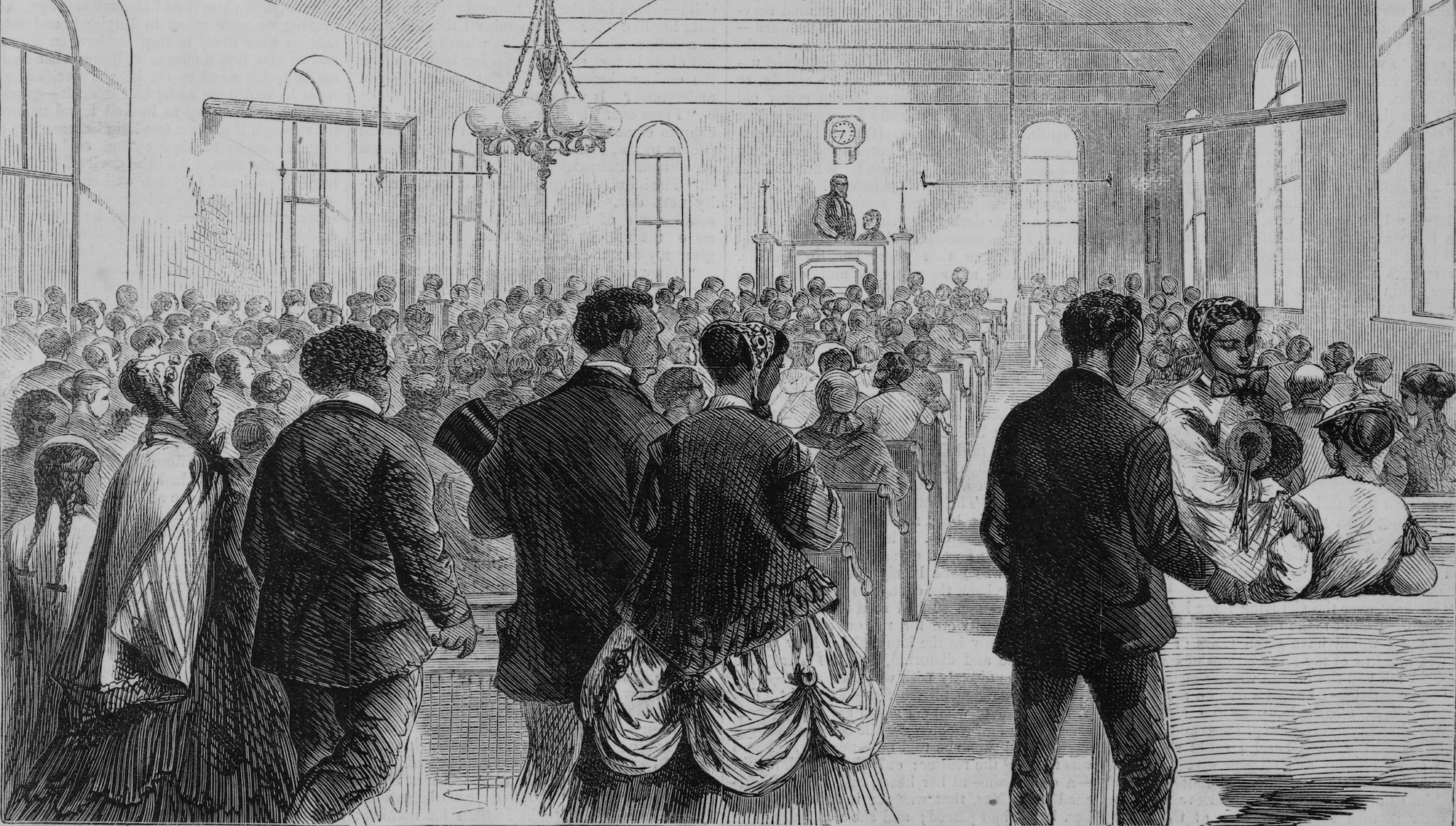

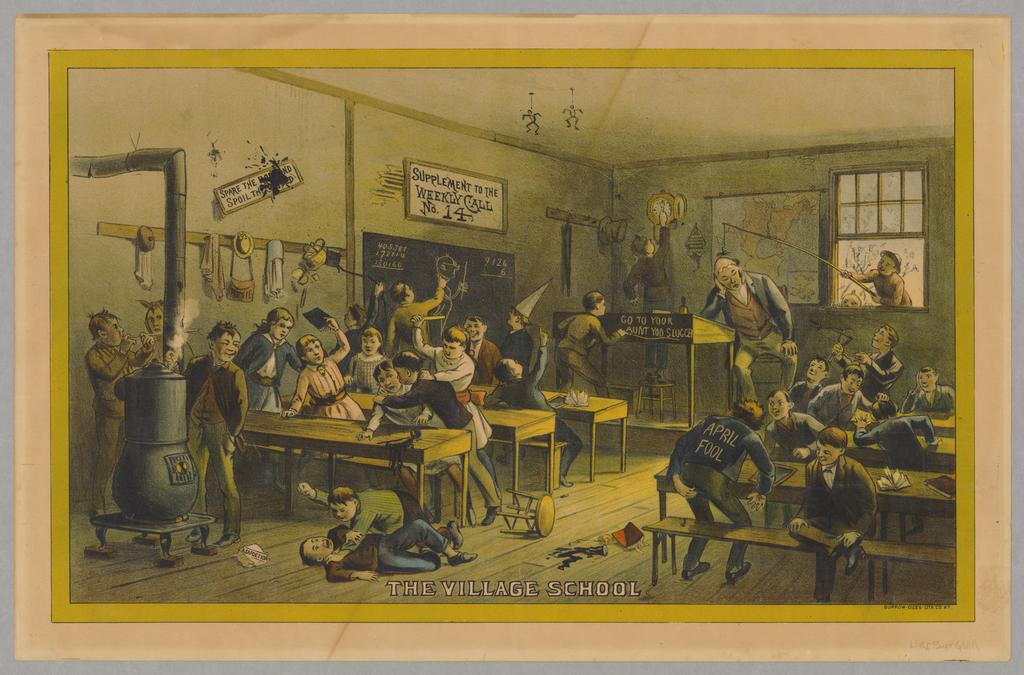

To my mind, no statistic better reflects how essential pawnbrokers were to the rise of capitalism than this: In 1828, New York City pawnbrokers handled over 181,000 transactions for the year, equaling nearly one item pawned for every man, woman, and child living in the city at the time. There is no denying that capitalism effectively padded the pockets of select, well-networked entrepreneurs. But these few winners were far outnumbered by the many losers, recorded as tens of thousands of individual transactions in pawnbrokers’ ledger books, evidenced by the countless bundles of pawns crammed onto pawnshop shelves (fig. 1), and the seemingly endless inventories of personal articles put up for resale at auctions of unredeemed collateral.

Mapping the geographies of pawnshops and capitalism provides another instructive glimpse into the concurrent spread of the two. As the country expanded westward in the 1840s and 1850s, pawnbrokers started appearing in cities such as Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Chicago. Like leading economic indicators, they signaled the maturation of capitalism in these places. Without enough consumer goods as collateral and a sizable population of needy people to patronize them, pawnshops would not have existed at all, let alone thrived for decades, through successive generations of proprietors. Pawnshops tended to cluster on the fringes of retail corridors and were often located near complementary businesses such as saloons and brothels—close enough to where concentrations of the working poor were living, and close enough to entertainment districts frequented by the middle and upper classes who made occasional visits to the pawnbroker for quick cash (much like using an ATM today).

Many pawners were women, and it was often left to them to keep the family afloat, a balancing act requiring skill and ingenuity learned through hard experience. They scrimped on clothing, patching and mending and buying secondhand apparel. They also consumed less food and cooked with inferior ingredients. But some expenses could not be massaged—rent in particular, what one scholar called “the one unending terror of life,” remained utterly fixed and inflexible, and many families lived chronically just one week or one day away from homelessness. To cover these and other essential expenses women turned to the pawnbroker, often their only lifeline, and they chose what items among the family’s possessions to hock, whether a treasured heirloom, a useful tool, or a decorative tchotchke. If a pawnbroker thought it had resale value, he would accept it as collateral. Pawnbroker John Simpson’s ledger from 1838 shows that women were pawning petticoats, handkerchiefs, linens, kitchen utensils, jewelry, and family Bibles.

Wives, in fact, often had a better idea of what household goods were worth and had more accommodating work schedules than did their husbands, and were therefore frequent patrons of the local pawnshop (fig. 2). And husbands did not always know what their mates were up to. There are accounts of pawnbrokers selling cheap brass wedding rings to replace the real ones wives pawned, and sometimes women would stash their pawn tickets (receipts needed to get their things out of hock) in tea caddies kept under lock and key. While family budgets of today may perhaps be more equitably managed, the practice of women independently pawning important collateral continued well into the twentieth century. One of the most evocative documents I came across during my research was an urgent letter that a pawner wrote to her Stockton, California, pawnbroker in the late 1930s. She was desperate to get her collateral back by mail, explaining to pawnbroker Ralph Hands, “I had to leave for Home on very short notice so it was impossible to get my rings. So you will find enclosed a money order for $5.75 and I will expect my rings in the following mail as my husband did not know they were in Pawn… I hope there will be no mix up or any trouble in getting them as it might cause serious trouble.”

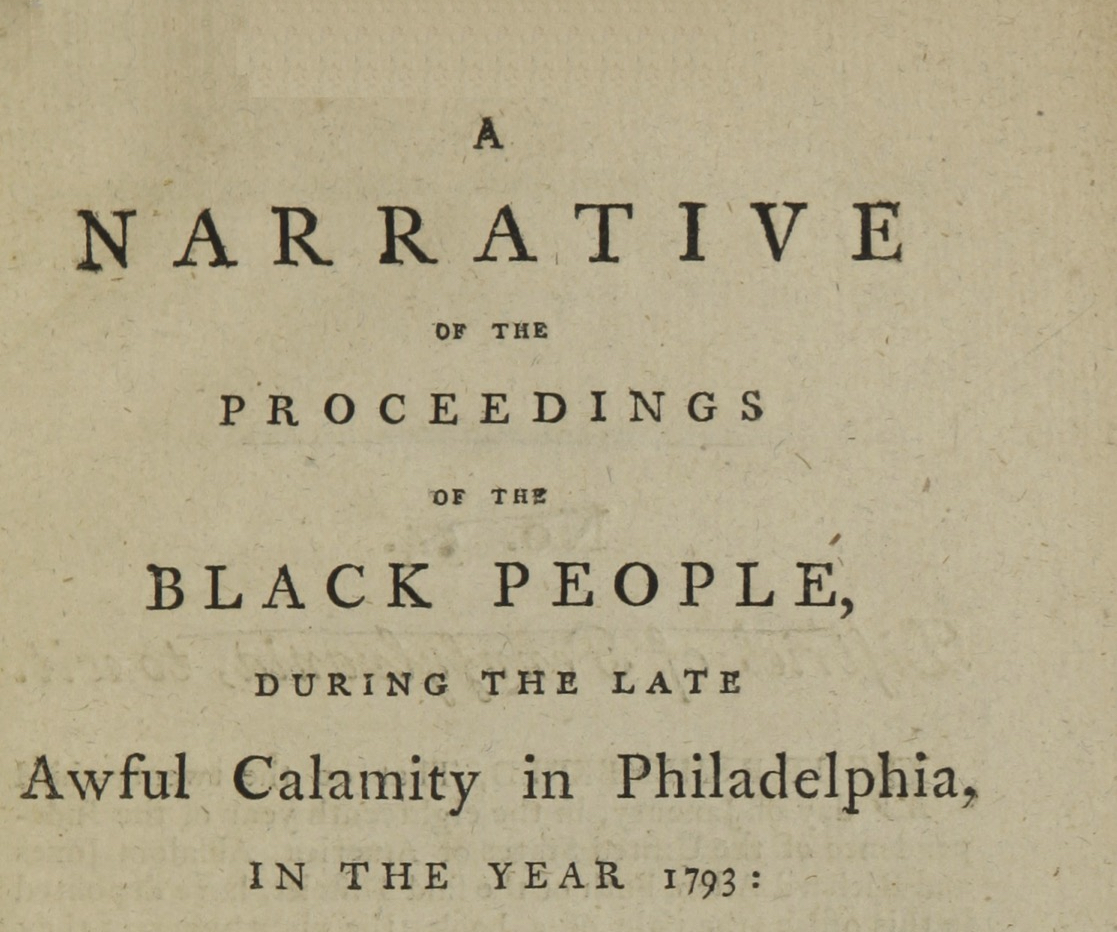

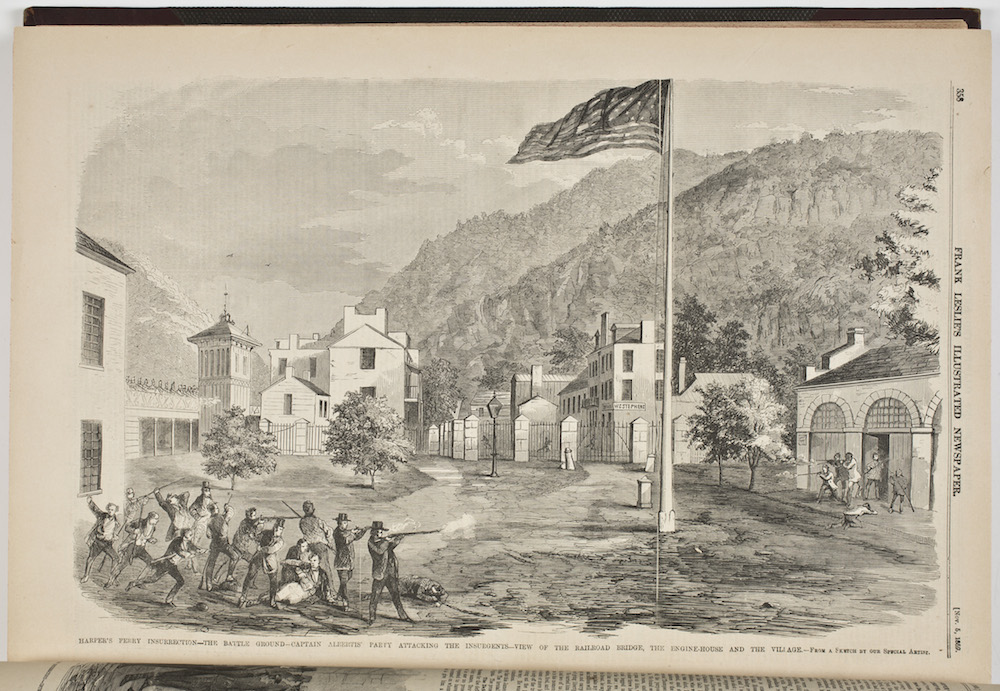

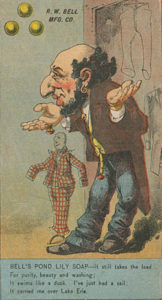

Because they were so ubiquitous and offered an essential service to the working poor, pawnbrokers were often stereotyped as being hard-hearted and greedy. Attempting to dispel any belief that capitalism and pawnbroking might be interlinked, reformers, politicians, and businessmen alike characterized pawning as an “aberrant” and “marginal” activity. So even though pawnbrokers were necessary to the continued growth and stability of the emerging economic system, they also became important scapegoats for the various social and financial ills that capitalism brought. It was in the interest of those who benefited from prevailing economic conditions—namely, those who were doing well—to reinforce the idea that pawnbrokers were fringe operators whose business was nothing like “mainstream” enterprises. While pawners were often faulted for not being able to handle their own money, the most vehement and direct criticism was aimed at pawnbrokers themselves, who, true to the stereotype, were initially Jews who came to the profession from the used goods trades. Although the complexion of pawnbrokers changed over time as the Irish and African-Americans joined the business, this stereotype remains firmly ingrained in the popular imagination even today. Anti-Semitic depictions of pawnbrokers furthered the larger endeavor to make other businessmen look good by comparison, defining pawnbrokers as threatening foreigners who looked strange, spoke an alien dialect, and engaged in shady or illicit business practices such as usury and fencing, accusations which were largely untrue. Surfacing as early as the eighteenth century, the stereotypes became more frequent in the nineteenth century, calcifying over time to such a degree that by the dawn of the twentieth century, Jews and pawnbrokers were practically interchangeable (fig. 3).

Some two centuries after it first appeared in this country, the sign of the three balls (which came from the motifs of European banking families’ coats of arms) still hangs outside many pawnshops, indicating Americans’ continued need for small, immediate, short-term loans. Yet our relationship with pawnbrokers remains fraught, and the stereotypes are still entrenched. The popular media often portrays pawnbrokers as trafficking stolen goods or engaging in some other illicit activity, and people’s gut reaction to pawnbrokers remains negative. The new reality television show Pawn Stars may have helped soften the rough image of the pawnbroker, but he still appears as a menacing figure in the popular imagination, perhaps only recently replaced by banking and insurance executives. What was true centuries ago remains true today, that pawnbrokers, operating all across the country, are still the lenders of last resort for people who don’t have bank accounts, don’t want to ding their credit scores, or own only modest collateral but need quick cash. Our present moment of economic crisis has had a surprisingly unifying effect. Hard times have trickled up, forcing the formerly rich and the downwardly mobile alike to hock their personal possessions with the pawnbroker. Equal opportunity reigns in the pawnshop, where one pawner’s DVD player is another’s Rolex watch.

This article originally appeared in issue 10.4 (July, 2010).

Wendy A. Woloson is an independent scholar and consulting historian living in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her research interests focus on nineteenth-century American consumer culture, material culture, and secondary markets. Her book In Hock: Pawning in America from Independence through the Great Depression has just been published by the University of Chicago Press. She is also the author of Refined Tastes: Sugar, Confectionery, and Consumers in Nineteenth-Century America (2002).