The examination of humanitarian politics vis-à-vis French settlers remains absent in the historiography discussing late modern Atlantic empires. The existing scholarship leaves unresolved questions about whether aid increased the former settlers’ dependence on imperial administrations (ultimately leading them to become useful “colonial communities”) or, conversely, if the various social crises they caused led to increased resistance and autonomy against imperial directives. Hence, the diverse portrayal of Acadian women by external observers challenges simple labels and probably suggests deeper cultural and historical uncertainties about the “Frenchness” or “Britishness” of their Atlantic world.

Further Reading

Archives Nationales (AN), « Secours aux réfugiés et colons spoliés », F/12/2740-2883.

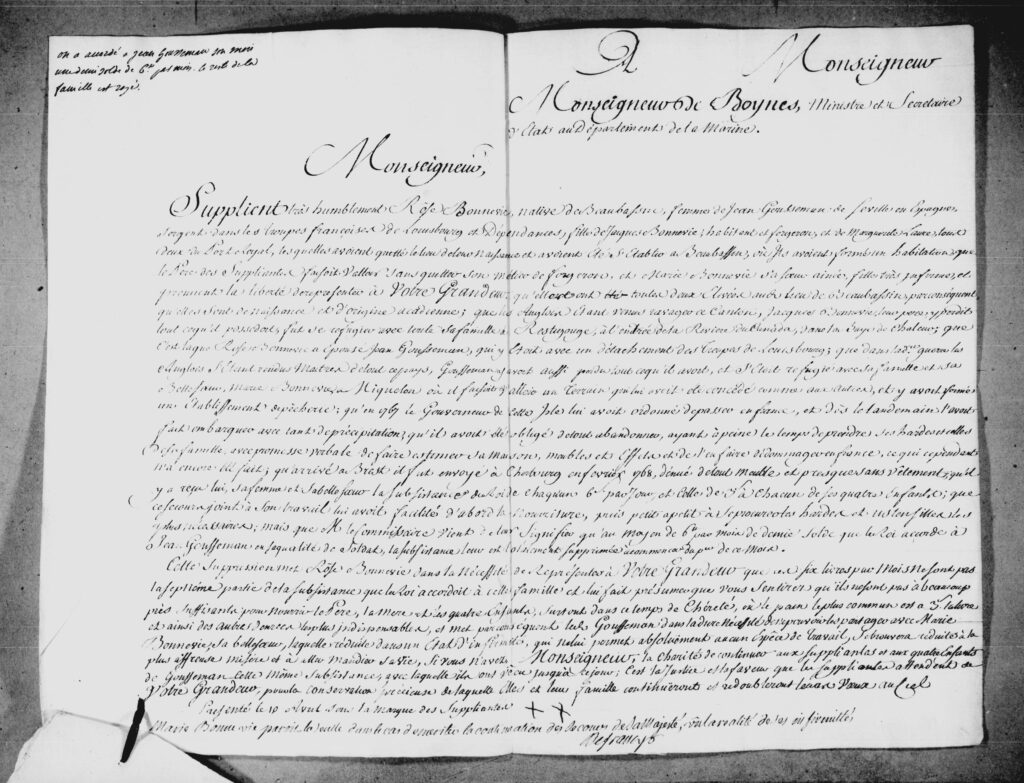

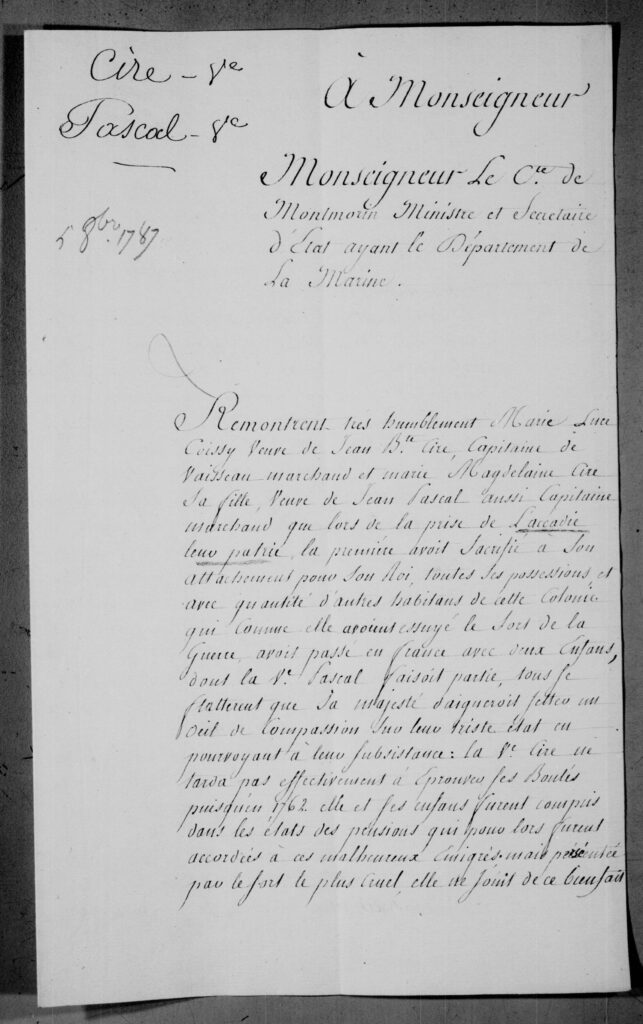

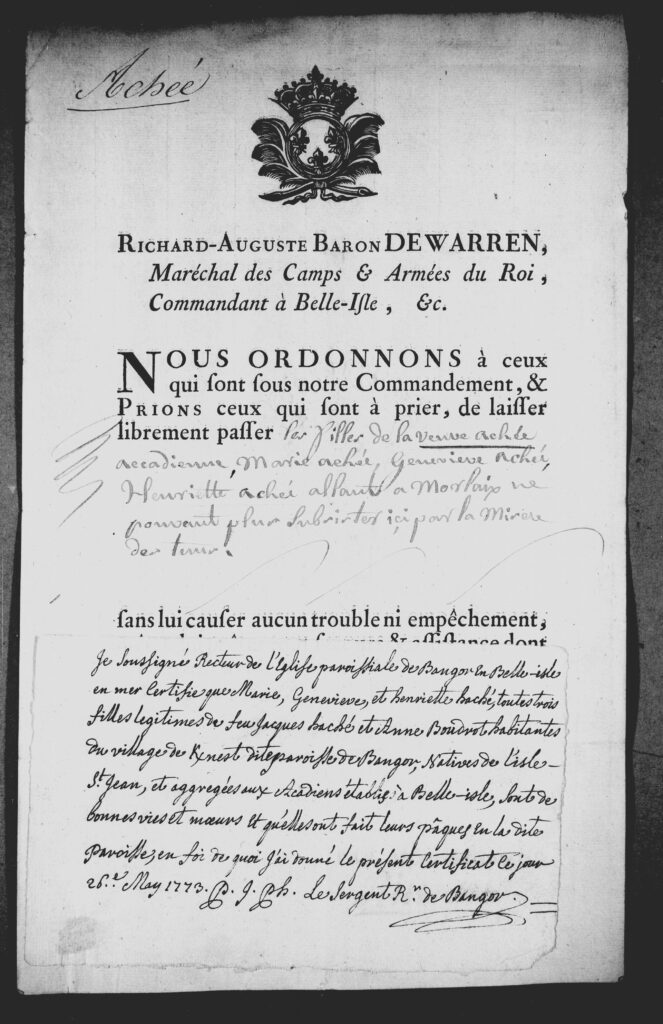

Archives nationales d’Outre-Mer (ANOM), « Personnel Colonial Ancien », Collection E 1, 40, 308 ; « Secrétariat d’État à la Marine, Correspondance à l’Arrivée », Collections C13 A 45, f.115, 118, 130, C14, E 318 Bis, Aix-en-Provence, France.

Massachusetts Archives Collection, “French Neutrals”, vols. 23 and 24, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston, MA.

Archives départementales d’Ile et Vilaine (ADIV) « Collection C 2453 », Archives et Patrimoine Ile et Vilaine, Rennes, France.

1755: L’Histoire et les histoires, http://cfml.ci.umoncton.ca/1755-html/.

Printed Sources

Thomas Hutchinson, The History of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, from 1749 to 1774, Comprising a Detailed Narrative of the Origin and Early Stages of the American Revolution, vol. 3 (London: John Murray, 1828).

The Diary of Ebenezer Parkman, The Ebenezer Parkman Project, https://diary.ebenezerparkman.org. Henri Têtu, Charles-Octave Gagnon, Mandements, lettres pastorales et circulaires des évêques de Québec, vol. 2 (Québec: Imprimerie Générale A. Coté, 1880).

Secondary sources

Uriel Abulof, The Mortality and Morality of Nations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Saliha Belmessous, Assimilation and Empire. Uniformity in French and British Colonies, 1541-1954 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

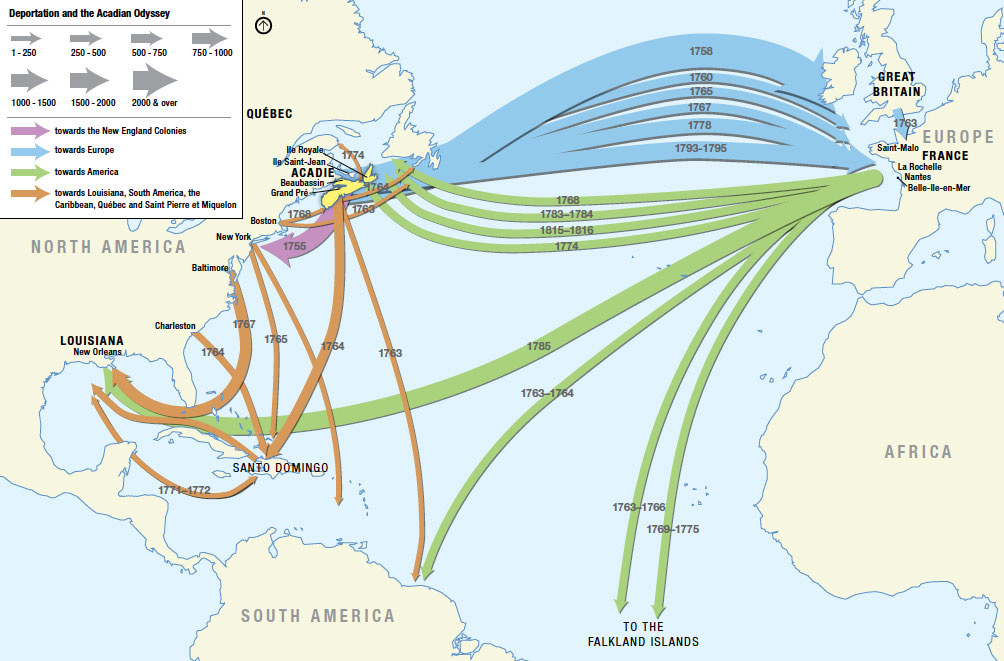

Carl Brasseaux, Scattered to the Wind: Dispersal and Wanderings of the Acadians, 1755-1809 (Lafayette: University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1991).

Christophe Cérino, « Les Acadiens à Belle-Ile-en-Mer : une expérience originale d’intégration en milieu insulaire à la fin du XVIIIe siècle », Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l’Ouest 110, no. 1 (2003): 115-24.

Nathalie Dessens, “The Saint-Domingue Refugees and the Preservation of Gallic Culture in Early American New Orleans,” French Colonial History 8, no. 1 (2007): 53-69.

Hilary Doda, “Scissors, Embellishment, and Womanhood: The Material Culture of Acadian Sewing to 1755,” Acadiensis: Journal of the History of the Atlantic Region 50, no. 1 (2021): 62-95.

John Mack Faragher, A Great and Noble Scheme. The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from their American Homeland (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), 390.

Alan Forrest, The Death of the French Atlantic: Trade, War, and Slavery in the Age of Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

Netta Green, “Longing for the Beheaded Father: Inheritance and Departmental Statistics under the Directory and the Consulate, 1795-1804,” French Historical Studies, 47, no. 1 (2024): 71-102.

Naomi Griffiths, From Migrant to Acadian. A North American Border People, 1604-1755 (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004).

Christopher Hodson, The Acadian Diaspora. An Eighteenth-Century History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

Allan Potofsky, “The ‘Non-Aligned Status’ of French Emigrés and Refugees in Philadelphia, 1793-1798,” Transatlantica 2 (2006), http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/1147.

Frédéric Régent, “Revolution in France, Revolutions in the Caribbean,” in The Routledge Companion to the French Revolution in World History, ed. Alan Forest and Matthias Middell (New York: Routledge, 2016): 61-76.

Peter Stamatov, The Origins of Global Humanitarianism: Religion, Empires and Advocacy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Adeline Vasquez-Parra, “Local Affairs or Imperial Scandals? The Rise of an Atlantic Legal Culture of Citizenship among Colonial Communities in the French Caribbean (1697-1789),” Journal of Early American History 12, nos. 2-3 (2022): 211-47.

Adeline Vasquez-Parra, Aider les Acadiens ? Bienfaisance et déportation, 1755-1776 (Bruxelles: Peter Lang, 2018).

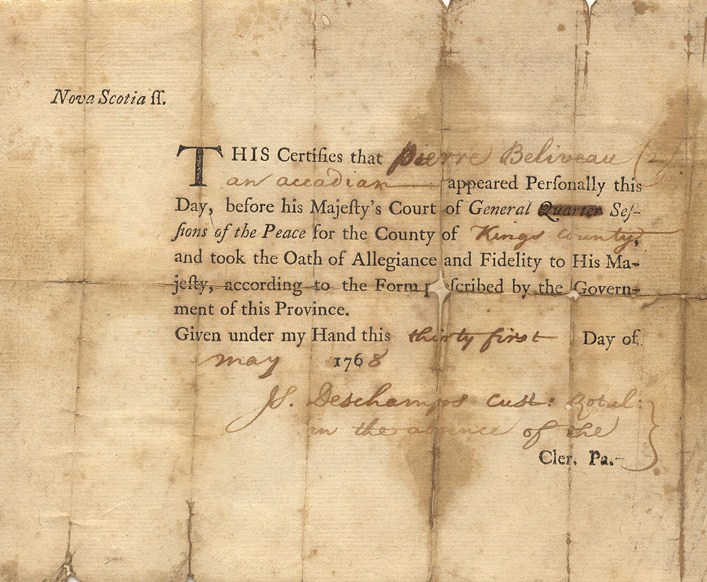

Many thanks to the George Godfrey Rodrigue Jr. Family Trust for granting permission to use the unique artwork by Louisiana artist George Rodrigue (1944-2013); to François LeBlanc at the Centre d’Etudes Acadiennes Ansselme Chiasson, Université de Moncton, Canada for providing the oath of allegiance; and to Netta Green, from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem for bringing the « Secours aux réfugiés et colons spoliés » to my attention.

This article originally appeared in June 2024.

Adeline Vasquez-Parra is an associate professor in American history and civilization at the University Lumière of Lyon in France and researcher at the Laboratoire Triangle UMR 5206. She has contributed articles on the Acadian deportation to scholarly journals such as Revue Historique, Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française, Acadiensis, and the Journal of Early American History. She is currently working on a comprehensive history of the province of Québec from its origins to the present day.