Presenting multiple perspectives, growing ideas

“We are about to embark on a journey! We are going to stand in the shoes of the men and women who made America!”

The call to participate in the Revolutionary Town Meeting rang out! Working closely, Dinah Cohen and I challenged the fourth graders to “become living replicas” of the significant historical figures of Revolutionary America. It was early in April, and the study of the American Revolution provided a perfect backdrop for the notion that all history is a story—usually a story told with a particular angle. Twenty-seven nine-year-olds traveled with us as we taught them to appreciate multiple perspectives, to reconstruct divergent points of view on independence, and to defend differing positions. The plan called for these young revolutionaries to deliver speeches, to engage in debate, and to share differing interpretations of the decision to sign the Declaration of Independence.

Developing the Content: Historical Context

Dinah Cohen was convinced from the first day that if we want children to write passionately, we must provide opportunities that allow them to step into those events. She wanted them to see “the gravity and the magnitude” of the times and “to live it!” First, she immersed the children in the historical context of the late 1700s. In addition to delving into biographical and background information, students investigated their figures’ actions and their figures’ reactions to events that led to the Revolution. Carefully checking for source reliability and validity, students examined primary and secondary sources from textbooks, trade books, and various Internet sites. Figure 1 details the way that Joe concisely summarized the expectations (“Joe” and other student names below are pseudonyms).

Building on the students’ systematic research skills, we designed scaffolds aimed at teaching these young historians the tools of the trade. We hoped to move children beyond knowing what to do towards knowing how to do it. We needed to teach children that if they really wanted to understand and reconstruct multiple points of view, they would need to actively “do history.”

Immersed in this rich historical content from texts, trade books, picture books, and children’s magazines, the children easily drew on a virtual toolbox of reading and writing structures. Multiple configurations of conversations erupted constantly: peer conferences, small group talks, whole-class conversations. Sometimes listening, sometimes coaching, Mrs. Cohen and I witnessed a myriad of conversational moves. These fourth graders expected their peers to substantiate conversation with content: names, dates, places, and events. Students challenged each other’s claims, asking for clarification or probing with new questions. Often simultaneously, these young historians were scattered across the classroom developing timelines or charts, jotting notes, and writing reflectively in response to a primary quote. Sitting silently in creviced corners or collaboratively paired at a table, children developed (and supported) theories about revolutionary independence using an impressive range of writing-to-learn strategies. Notebook pages were littered with marginal notes, Venn diagrams, questions, quick writes, and double entries coupled with conclusions.

Growing Interpretations: Constructing Meaning

Two weeks later, a quick scan of this fourth-grade classroom revealed pint-sized historians engrossed in content research. Collectively, these young Abigails and Thomases accumulated an inspiring arsenal of textbook and trade book chronicles. Eavesdropping on their conversations and peeking into notebooks convinced us that these children could fluently spout multiple authors’ perspectives on independence. Clearly, our historians were ready for a bend in the road, and it was time to teach children how to reconstruct divergent viewpoints, searching for the meaning of independence for themselves! In a simple, yet significant teaching move, we taught the students to hold onto and extend the connections that they were making among the different document sources in two key ways: “writing-to-learn strategies” and “social studies talk.” A look into Matthew’s work provides a window into this approach.

Focused on a single page of text, Matthew thought out loud: “So Thomas wrote a book, Common Sense. He thought it’d change people’s minds.” Almost immediately, Matthew narrowed his search, ready to find evidence to support his idea that Paine valued independence. Matthew moved from text to text; read, then reread; and then focused on pictures on the side panels. Throughout the process, Matthew chronicled the events of Thomas Paine’s life in his notebook, citing sources and liberally using marginal notes to agree, and then disagree, with varying authors’ presentations. In a conference with his teacher, Matthew compared his process of putting together different pieces of information as he developed his ideas about Thomas Paine to collecting the pieces of a pie: “one piece, two . . . until I get the whole story.” Matthew began his notebook entry,

Evaluation: Living the Mantra

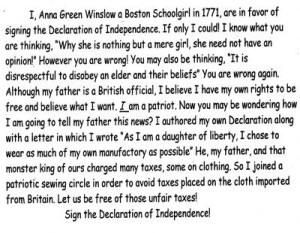

In a deliberate three-stage series of lessons, we implemented the second planned and purposeful teaching move. We taught the children to defend differing positions. First, we taught them to replicate (in dress and action) the designated historical figure “who changed the world.” Next, Mrs. Cohen and I taught the fourth graders revision strategies that focused on first-person narration weaving direct quotes with thinking. Finally, we taught our historians to “have a conversation” with their listeners. A close look at Jenny’s progress through her final preparations for her role as Anna Green Winslow in the Revolutionary Town Meeting shows the effects of this teaching on her ability to construct and defend her decision to sign the Declaration of Independence.

Jenny used the final days before the meeting to become a living document, authentically replicating twelve-year-old Anna. She designed her costume to include layered petticoats covered with a simple, hand-sewn, buttoned dress, capped by a matching bonnet. In her left hand she carried a basket with cloth and an array of needles. Tucked into her basket were original diary entries, marked with the words: Spinning for Liberty. In a conversation with Jenny, the fourth grader filled us in on her research to date: “So, I wrote a page about Anna . . . she joined a patriot sewing circle and helped the cause of Liberty.” Jenny elaborated, “They were sewing to protest British taxes by making their own clothes so they wouldn’t have to pay for it from England.”

At first, Jenny read and reread Anna’s diary, listing evidence that supported a patriot stance. With guidance, Jenny revised her first ideas. After underlining the fragment, “I might have told you that notwithstanding the stir about the Proclamaiten, we had an agreeable Thanksgiven,” Jenny almost automatically combined the two skills at her fingertips. First, Jenny’s prior examination of the Proclamation of 1764 allowed her to make sense of this statement, and more importantly, her prior knowledge helped her recognize its potential to support her angled position. Jenny worked through the statement, taking precise one-word notes in the margins of the diary: “annoyed,” “disturbed,” and “bothered.” She concluded, “maybe Anna was annoyed or bothered by the stir of the proclamation.” In this entry, Jenny not only added new content details but also began to incorporate her thinking.

Those last sessions before the Revolutionary Town Meeting were sprinkled with revision conferences. Mrs. Cohen taught the speechwriters deliberate grammar choices that allowed them to incorporate passion into their conversation with the listener. Jenny opted to speak directly to her audience. She began, “You must be thinking . . . ” Furthermore, Jenny learned that she could couple her systematic use of the present tense with judicious control over the exclamation point, e.g., “If only I could!” These moves added specificity, credibility, and power to the final version.

Conclusion

The spiraling effect of Mrs. Cohen’s direct, angled teaching was simple, yet significant. These children actively constructed versions of the call to independence in 1776. This active participation resulted in students who made informed decisions, developed reasoned arguments, and engaged in problem solving.

The Revolutionary Town Meeting proved to be an enormous success. Mrs. Cohen managed to teach her fourth-grade students how to “get the person in their heads.” Early one June morning, twenty-seven nine-year-old historians took the stage and passionately proclaimed the ideals of 1776, advancing the mantra: “These were people who changed the world!”

This article originally appeared in issue 7.2 (January, 2007).

Paula S. Marron is the assistant principal at Chatsworth Avenue School in the Mamaroneck School District. She conducted research on writing as the thread for higher level thinking in social studies in elementary classrooms on Long Island and in New York City.