I Am From the Future

Life without pipes

is not life. This is not a

pipe. It’s a rose

about a rose about a poem

about a pipe. Now here come I

with my bag of inventions

charioting through

the time/space continuum

fiddling with the buttons

on my coat. I did not invent

the wayward air here.

Sometimes

a life is just a pipe.

Another Sip

Primed for horseless trains to change

its very shape,

the nation,

capital-based to the core of each individual

citizen,

is working.

The sky below is white as a lab coat.

He takes another.

The Darkest Night Is History

Laid are the wires

The infrastructure

Begged them to

On the corner

Of the kitchen counter and

The egg counter and

The news ticker

And intuitively

Tonight will be artificial

If the cord fits

It only gets brighter from here

Words of Wisdom

New in town

New to the concept of

New in town

What’s a technology

Anyway

Technology is a fork

The visiting poet said

I thought he meant metaphorically

Later it came to me

He meant even forks

Often I Am Permitted To Recall How

I was at home in that chronotope,

that way of being awake.

I read a mediocre novel about the golden age

of artificial sweeteners

as I rode a cross-country train.

Prisoners made license plates,

I think,

and we wore them on our cars.

Although I didn’t necessarily like it,

without it I’m unreadable.

You should see the future

from this wide-angle lens.

A dry field with patches

of long grass from time to time

to time, however and ever the end.

Long After Adorno

There’s nothing wrong with this century

Every atrocity

I’ve assented to

Or pulled over

To let pass

There’s nothing wrong with this century

That hasn’t been wrong before

On this Highway

By my voice

Or my choices

Do you know me

I don’t feel very well as I write this

I’m not a barber

Or in an ancient mood

I’m not a barbarian

But I’ve been wrong before

I don’t feel very well as I write this

I said nothing

Statement of Poetic Research

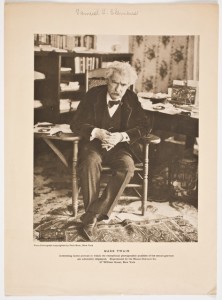

Mark Twain’s Lucy Biederman.

These poems are my unsuccessful ventriloquisms of Twain’s character Hank Morgan, the nineteenth-century time traveler of A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. And they are my account of what I cannot ventriloquize about Twain or Hank Morgan. I keep poking through.

Mark Twain’s America.

A trickster, Missouri Compromiser, Twain seems to be nearly every kind of American regional writer: Western, Midwestern, Northeastern, Southern… Mark Twain of Quarry Farm, Elmira. Mark Twain of Hannibal, MO. Mark Twain of Buffalo. Mark Twain of Carson City. Hartford Mark Twain. Mark Twain Abroad.

I’d do that. It’s that shiftiness about him I most understand. Maybe he was looking for unincorporated territory, but he canonized every place he landed.

Mark Twain’s Middle Ages.

Looking back through my notes about Twain, I see that at one point I made a list of some of the “technologies” that Hank introduces into sixth century life:

A lariat

Gun-powder

A pipe

Sandwich-board advertisements

The telephone

Newspapers

Toothbrushes and toothpaste

A bomb

Soap

Guns

Trains

Electricity

Mark Twain’s Jokes.

The narrator-protagonist of Jenny Offill’s recent novel-in-fragments Dept. of Speculation confesses,

“Three things no one has ever said about me:

You make it look so easy.

You are very mysterious.

You need to take yourself more seriously.”

No one would say those things about me, either.

But I would say all three statements of Twain.

Leslie Fiedler: “American literature likes to pretend, of course, that its bugaboos are all finally jokes.”

In “the poisonous air bred by those dead thousands” at the end of Connecticut Yankee, there is a competition for the last laugh, as Hank exits the scene, leaving his right-hand man Clarence to “write it for him” in a postscript. Clarence recounts the death of Merlin, who, in “a delirium of silly laughter,” accidentally electrocutes himself:

“I suppose his face will retain that petrified laugh until the corpse turns to dust…”

Enter “Mark Twain” in a second postscript, knocking politely on Hank’s nineteenth-century door. Hank is let loose again, in all his confusion, “delirium, of course, but so real!”

Mark Twain’s Apocalypse.

Connecticut Yankee: “To-morrow. It is here. And with it the end.”

Mark Twain’s Theses.

I usually assume I’m right, until I find out I’ve been wrong, and then I turn over easily, like a new engine. That’s me, Lucy.

A picaresque with a thesis, two theses, many theses pointing in many directions: That’s Mark Twain to me.

Mark Twain’s Pipe.

Everett Emerson: “Clemens’s favorite location for smoking was bed. … And the woman who shared the bed of an inveterate smoker through three decades of an apparently happy marriage was more than inconvenienced; she was victimized.” I couldn’t stop thinking about this for a while after I read it, then I thought of it again watching the Ken Burns documentary about Twain, photographs giving way to each other in the Burnsian style, like thick curtains parted to reveal more curtains, Twain smoking in Connecticut, Twain smoking in Italy, Twain smoking after his poor wife, Olivia, started dying, and, then, as he grieved Olivia, smoking.

Mark Twain’s Details.

When I was a little girl, I used to be afraid that I was only the person in the world who had ever read certain dusty “chapter books” from the library. It made me feel terribly lonely, until my mom explained to me that every book, at the very least, went through an editor.

Deep in the current of a Twain novel I recall that old feeling, as if some of the scenes Twain wrote weren’t intended to be read. Looking closely at such scenes, it seems I am working at cross-purposes to the books in which they appear, taking it too seriously. Those people shut up in the dungeon in Connecticut Yankee, for example. “Their very imagination was dead. When you can say that of a man, he has struck bottom, I reckon; there is no lower deep for him. I rather wished I had gone some other road.” The tortuous ins and outs of Tom Sawyer’s tricks. One particular scene in Roughing It, which I think I care more about than Twain seems to, even though he’s the one who almost died, caught in the cold overnight with no sign of safety. “We were all sincere, and all deeply moved and earnest, for we were in the presence of death and without hope. I threw away my pipe, and in doing it felt that at last I was free of a hated vice and one that had ridden me like a tyrant all my days. … Oblivion came. The battle of life was done.” Of course it’s a trick, a joke: Two pages later our narrator is smoking in perfect hilarity. I should have known better. Twain brings characters back around, he reprises, but he keeps it moving: down the river, through the centuries, way out West. Away from our bugaboos.

Mark Twain’s Beauty.

Like John Berryman, Grace Paley, Alice Walker, geniuses of the American vernacular who write in Twain’s grainy shadow, the beauty of Twain’s writing frustrates. It hides itself when excerpted, or masquerades as cute. There’s a quality to Huck Finn’s curiosity—when he describes the Grangerfords’ tacky house, for example—that I can’t convey without “quoting” all of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, every single word of it.

Twain is more beautiful and baggy and bad to me than any excerpt would show.

I take him seriously.

This article originally appeared in issue 15.4 (Summer, 2015).

Lucy Biederman is a Pushcart Prize-nominated poet and doctoral candidate in English at the University of Louisiana-Lafayette. Other poems of hers inspired by the literature of early America have recently appeared online at Sixth Finch, La Vague, Elsewhere, and Unsplended, and are forthcoming in The Minnesota Review and The Laurel Review.