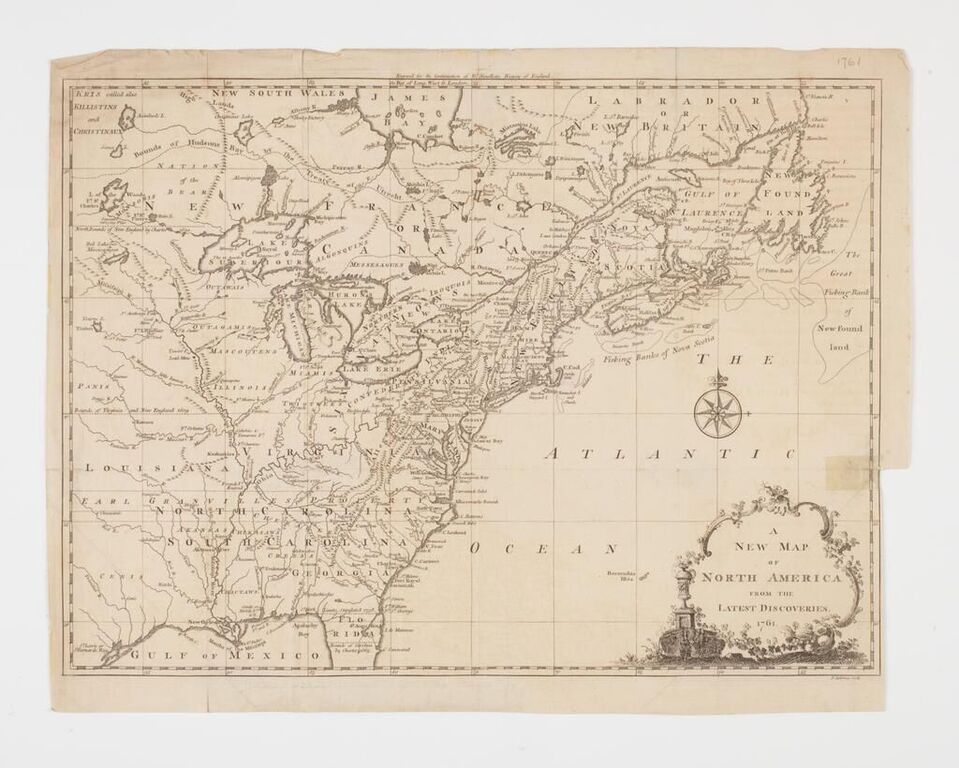

The carte of all the coaſt of Virginia

To appease Fancy

I drew mythic beasts wallowing

In indulgent waters

But here everything is a myth alive,

The light that falls, Heavenly declaration,

Makes sweet earth Sovereign

& like the Picts of old

The people draw pictures on themselves

Ashamed not of nakedness—

Mapped from the eye of God

I meant to show it, the bow-shaped archipelago

Wokokan Croatoan, Paguiwac & Hatorask

Second-hand signs for tongues

Gone the way of runes—

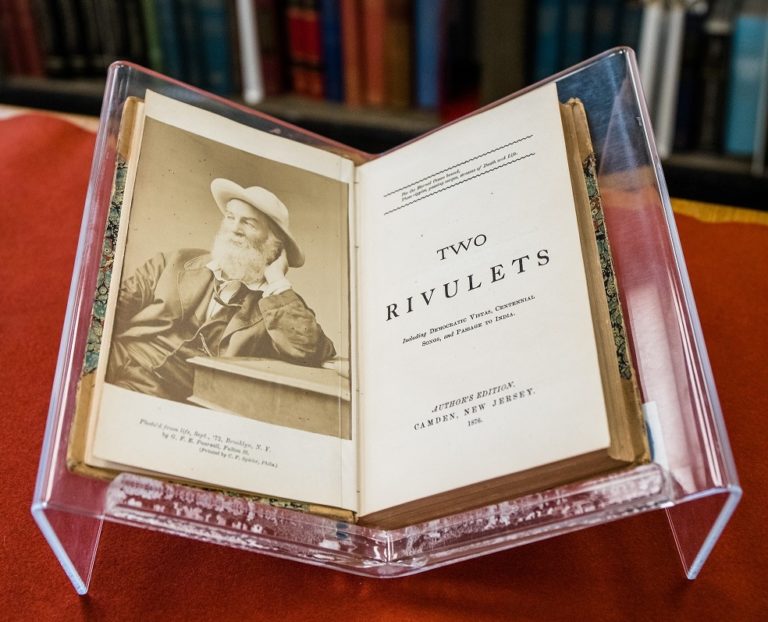

That world, a book of wonder

Book of fright—

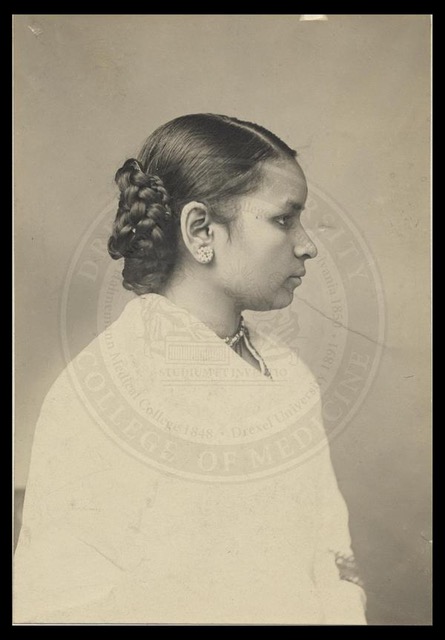

A Weroan or great Lorde of Virginia

Absolute symmetry of the body,

as “front” & “back.”

All the beauty of it.

No fact

Separate from the myth.

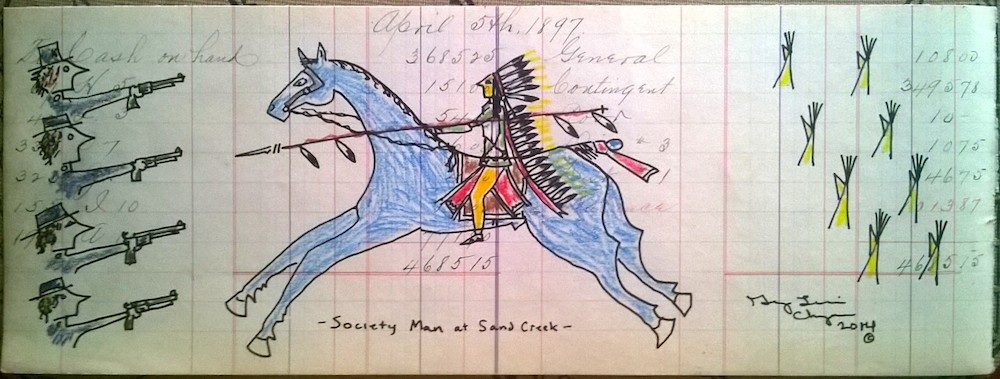

The birdfeather-plumed face

Half hides itself

In studying last year’s hunt

Unfolding on the plain below—

All the aiming & pursuing

Relives the past

Next to the river’s unpassing.

In the distance

The hunt is renewed.

All the hunters have drawn

Their bows

& the stag

Is leaping into the stag-sized trees

A cheiff Lorde of Roanoac

He has a natural dignity

& grace & needs nothing

To prove himself.

Adept at reading signs,

They need not our script.

This is a story

Of disappearance

Unaccompanied

By wonder.

What a wandering

In the black back-lit lines,

The empty white spaces.

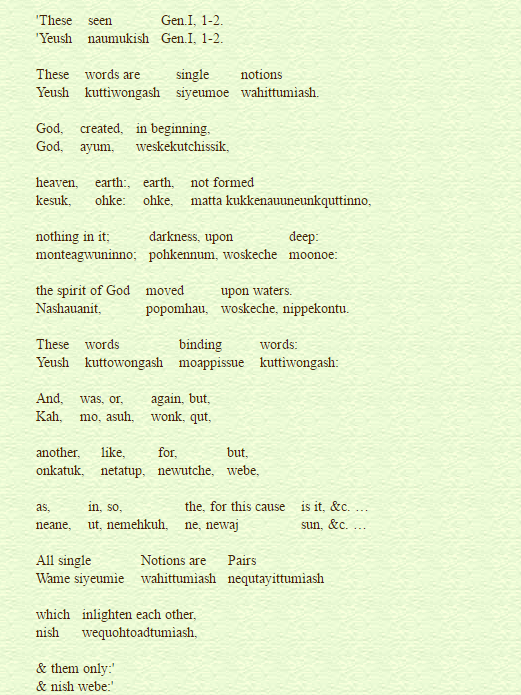

The Marckes of Fundrye of the Chief mene of Virginia

They write marks on their backs

Signs by which they make

Known whose subjects they are

Alphabets made of arrows

With strange crossings—

The letters they carved into trees—

I willed them that if they happened

To be distressed they should carve

A cross over the letters

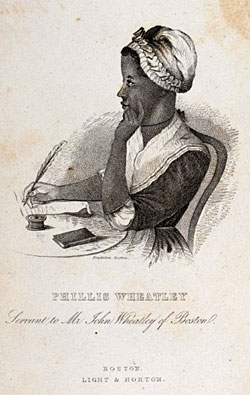

Every sign is a stranger now

No language have I left to speak

Of trees & men-bearing signs

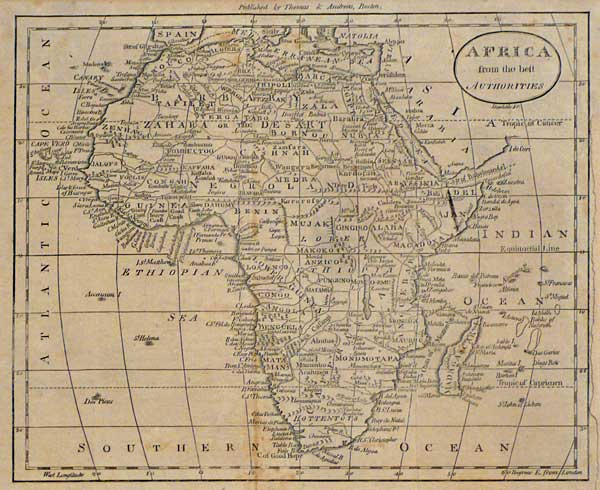

Statement of Poetic Research

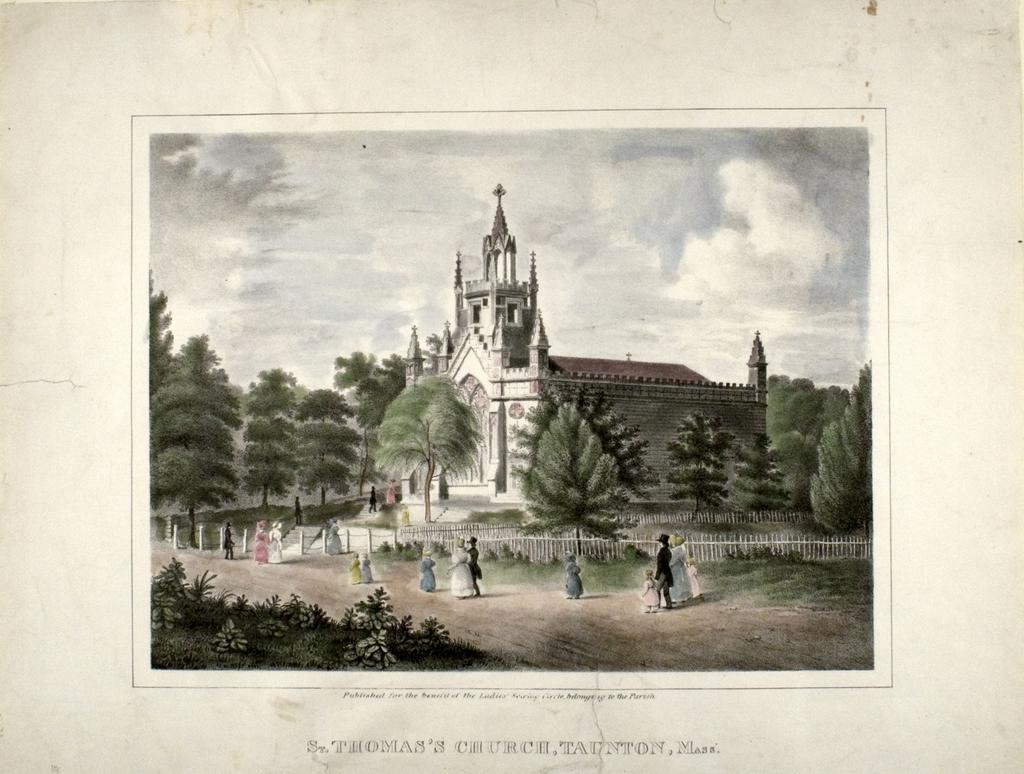

I first came across Thomas Harriot’s strange and wonderful account, A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (1590), in the large, sepia-toned Dover edition—”The Complete 1590 Theodor de Bry Edition”—on the shelves of the university bookstore. It was a singular discovery. John White’s images—and the engravings that Theodor de Bry made of White’s work—capture the wonder of a sixteenth-century Elizabethan world encountering the “exoticism” of a very different New World civilization. While the intense realism of White’s work, almost dreamlike in its detailed rendering of the ordinary life of the Algonkians, first riveted me, I was ultimately drawn to the unknown questions surrounding John White’s work—who was he? Under what circumstances did he meet the Algonkians? What is the story of the individuals he represented? What became of his story? While I followed the story of his life and times (Lee Miller’s Roanoke was especially memorable), the historical record does not provide answers to these questions: gaps and blanks define his story. For me, poetry’s strength is not in laying out an historical record with a fully-realized narrative. Instead, it excels at thinking about gaps and silences—it excels, in other words, in registering a sense of the immediacy of experience, its felt richness, its always-already vanishing moment. In imaginatively engaging the past, poetry can interrogate the completeness of narrative, the completeness of our assumptions. Through its openness to multiple forms of intelligence, poetry can approach the silence of history and the specters who dwell there. Indeed, poetry has the power to give voice to some of their whisperings, however incomplete those transcriptions—translations—may be. John White is one of these voices.