Statement of Poetic Research

“If you would learn the earth as it really is,” N. Scott Momaday writes, “learn it through its sacred places.” For many years, I have been visiting pictograph and petroglyph sites in Montana and the West, reading the archeological research and tribal records, and consulting with area archaeologists, hoping to gain a deeper understanding of the place where I live. “What we mean by place is a crossroads,” writes Rebecca Solnit in her book Storming the Gates of Paradise, “a particular point of intersection of forces coming from many directions and distances.” In Montana, as I’m sure is true of all places, that intersection is complex. There are sculpted mountains, limestone canyons, glacial erratics and volcanic seams, the ice age having covered the land so long that that making seems new and ongoing. As South Dakota novelist Kent Meyers writes, “The surface of the continent is literally older [in the West]. There is no new, thick topsoil to cover the evidence of former years, nor is there enough rainfall to support plant life abundant enough to prevent the erosion that year after year reveals ancient burials. Time is always being stumbled over here.”

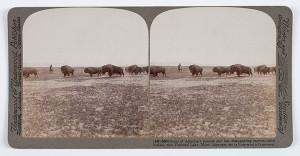

This land, fragrant with multiple species of sage, or dark with Douglas fir and Ponderosa pine is not, however, untouched. In fact, it is over- and under-laid with thousands of years of indigenous occupation, language and trade and trails, as well as the later Indian massacres and broken treaties, reservation land divided by sale of allotments, and the wholesale slaughter of buffalo. Montana, which we praise for its recreational opportunities, has been recreated over ruins, has built itself wholesale over cultures whose visionary images, depicted in pictographs, still watch, many of them “undiscovered,” from the grottos and caves above us. “The counter-history of the indigenous people,” as Solnit writes, includes the various ways the land has been ceremonialized by them, ceremonies whose purpose was to keep alive a relationship between the human and the animals, plants, trees, elements, and the dead.

The sites where the pictographs and petroglyphs were made are some of the most beautiful places I have ever visited, sun-splashed gulches blooming with cream-colored yucca and a strange pink-orange paintbrush, prickly pear cacti, the threat of snakes, places over-hot and lush with sandstone hoodoos and pinnacle rocks guarding them, places where one could see no one for fifty miles, places imbued with their past, a single eagle or hawk, and baskets of rock wrens. And high caves that overlook entire watersheds. Here are some of the names: Valley of the Shields, Weatherman Draw, Bear Gulch, Perma, Sun River, Medicine Wheel. A number of sites have been completely destroyed by vandalism, graffiti, and theft. I visited one remote cave where, the ranchers told me, curators from the Smithsonian had come decades ago and chiseled out the central pictograph and taken it with them. Some are known only to a very few. Some, like Pictograph Cave, outside Billings, Montana, or Writing-on-Stone in Alberta, have become part of the national park systems and are being protected and preserved.

Petroglyph: Castle Gardens

Late morning, strange, a kind of music. I was in love with earth again. I wanted to stay forever as with a Person. Corridors of sandstone, the white, orange-rose. A flour batter poured into sloping pans that overflow into a sphere larger, more varied than we can travel. There was color where there is no color, inside the abraded circles and incised lines, only a fugitive green or violet, resembling fresco. Like the wash of lilac through the mind when one says lilac. Or shadow limbs between real limbs a painter sketches in space only to suggest the complications of lineage. Because there were no horses yet, the walk must have taken weeks, a hundred miles through sage and rabbit bush, far from water and trees. The ground friable, like stepping on wetted ash. They must have set alive a fragrance burning. To prepare their ancestral homeland. To pace themselves inside the dream. That we might have at one time added something to it.

Moving Pictograph: Parenthetical Signs of Spring

In the winter twilight, below the mountain—violet, aqua—the brown prairie unrolls in bolts of suede. The snow patches gather and disperse like herds. The mythic snow deer is what we say. One sole bluebird detaches itself from the sky, that trick most wild things play, which enables us to see the hundred more. The clouds, frothy and wild, tossing their manes and tails, prepare for what they will be: tomorrow. Goatsuckers and swifts. Nightjars and nighthawks. Two false eye spots, high rattle or trill. All things cryptically colored. Like the lynx in the ditch you have longed to see all your life. Like the reindeer. Like the shaman. An animal runs across the road, dives into the ditch, its ears like the forked and broken tines of dogwood. This is the important point: where vision came. And also, at the same time, the vision.

Questioning the Dead

Look how they go on without us, how they already existed when we arrived. On the other side, I have learned to say, but they’re not somewhere else, they’re here, in the green haze about the limbs, between me and that row of cottonwood barely budding. Like the culvert I came to yesterday, the backwater still. I saw what I usually see: the shoreline, the surface, not the upside down trees, which then swayed into being, though darkly. What is the nature of the eye’s adjustments? Take this valley, for instance—where would the dead be? If I hung cloth on the limbs, would they lift it? At what stage do we lose our precious names? Our symptoms? Our traceries? Our handicaps? Our turns of phrase? The shadows we lug everywhere, like an overfull valise? Earth the cool clay tablet where we set it down. I have been wrong to confront them so directly, to stare into the photographs of their battlegrounds.

Further reading

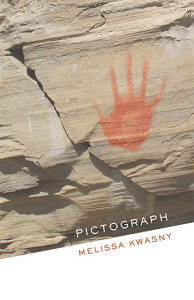

The poems included here are included in my most recent book of poems entitled Pictograph (Minneapolis, 2015). Coterminous with the writing of the poems, I was also writing a long essay, entitled “The Imaginary Book of Cave Paintings,” which appears in my collection of essays, Earth Recitals: Essays on Image and Vision (Spokane, 2013). Informing both the essay and the poems were my research trips, as well as my relationship with Sarah Scott, a Montana State archeologist working to preserve rock paintings. I was also enormously educated and influenced by a number of amazing contemporary books on the subject. For recent theories on cave painting as a neurological expression of shamanic activity, see David Lewis-Williams, The Mind in the Cave (London, 2002). I was convinced by the author’s theory of a “spectrum of consciousness,” with ordinary waking consciousness on one end and the visions of a shaman on the other, and his belief that we all move up and down the spectrum at various times and with various experiences. On shamanism in general, see Mircea Eliade, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy (London, 1989); Piers Vitebsky, The Reindeer People (Boston, 2005); and Clayton Eshleman, Juniper Fuse: Upper Paleolithic Imagination and the Construction of the Underworld (Middletown, Conn., 2003). For archeological research on pictographs and petroglyphs in the West, see James D. Keyser and Michael A. Klassen, Plains Indian Rock Art (Seattle, 2001); David S. Whitley, The Art of the Shaman: Rock Art of California (Salt Lake, 2000); Alexander Marshack, The Roots of Civilization: The Cognitive Beginnings of Man’s First Art, Symbol and Notation (New York, 1972); and Julie E. Francis and Lawrence L. Loendorf, Ancient Visions (Salt Lake, 2002). The latter book led me to visit Castle Gardens in southern Wyoming one late May morning, an unmarked site reached by dirt road far from any habitation, in the middle of hundreds of miles of sagebrush flatland. Alone, wandering paths between sandstone hoodoos and pinnacles, I soon was imagining how terrifying and ecstatic it must have been for those traveling by foot for days to encounter images of animals and gods a thousand years old. On the visionary imagination in general, see Henry Corbin, Spiritual Body and Celestial Earth (Princeton, N.J., 1989), as well as Avicenna and the Visionary Recital (Princeton, N.J., 1990); James Hillman, The Dream and the Underworld (New York, 1979); Adonis, Sufism and Surrealism (London, 2005); and John Berger, “The Chauvet Cave,” in The Shape of a Pocket (New York, 2001).

This article originally appeared in issue 15.2.5 (April, 2015).

Melissa Kwasny is the author of five books of poetry, most recently Pictograph (March 2015), The Nine Senses, and Reading Novalis in Montana, all from Milkweed Editions. A collection of essays, Earth Recitals: Essays on Image and Vision, was published in 2013. She is also the editor of Toward the Open Field: Poets on the Art of Poetry 1800-1950 and co-editor of an anthology of poetry in defense of human rights, entitled I Go to the Ruined Place. She lives in western Montana.